5. Pagans, Heathens, Infidels, And Heretics

The terms “pagan”, “heathen”, and “infidel” get bandied about a lot in modern English vernacular. Quite often, each gets used to hint at (or as a direct synonym for) “godless” (which none of them actually means).

For the proper study of mythology, however, we need to have a better, fuller understanding of the history and historicity of these terms.

Pagan

“Pagan” comes (ultimately) from the Latin word pāgānum, meaning “peasant” or “rural”, and which was derived from pāgus, meaning “village” or “rural district” (cf. Greek πόλης (polis), “city”). The Latin word thus had a primary meaning of “one who dwells in the country”, in contrast to urbānum, “of or belonging to a city”.

With the rise of large cities and social stratification, “town-dwellers” often had little-or-no contact with country-dwellers or the particulars of their lives and livelihood. (There are inner-city residents in our own society who may go their entire lives without encountering farm animals in any situation other than a petting zoo.)

So, there were people living and working in the city (“civilians” or “citizens”, from the Latin civis), and there were people living and working in the countryside. The country-dwellers were of two main types: agriculturalists (farmers) and pastoralists (herders). They tended to remain “closer to nature” than the city-dwellers. As often remains the case today, these country-dwellers were viewed by the city-dwellers as “quaint”, “backward”, “naïve” — as “bumpkins” or “hicks”.

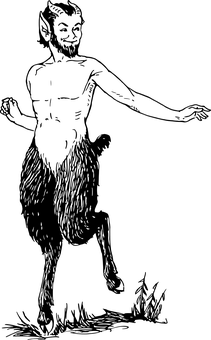

These pāgāna, because they still tended to crops and animals, also still tended to worship (or at least show reverence to/for) the older nature-based deities (e. g. Faunus [Pan in Greece, shown at right figure 5.1], Ceres (Greek: Demeter), etc.). This reverence was sometimes even in preference to or instead of the official state gods (who, in Rome, were, of course, largely borrowed from the Greeks).

So, “pagan” originally meant simply “a country-dwelling worshiper of the older nature spirits and deities”. As such, it didn’t carry much more of a negative connotation than being “from the country” does among enlightened urbanites today.

Heretics and Heresy

In 325 CE, the Roman Emperor Constantine I (“the Great”), called an ecumenical council (it was the seventh such council to be called; the earliest had been in 50 CE, in Jerusalem). The council was held in the small Anatolian town of Nicaea see figure 5.2, and charged with producing a document which defined Christianity once-and-for-all: its beliefs, practices, doctrines. It was the first attempt in the history of the movement to achieve a consensus through debate and compromise. Which it did, mostly.

The result was the Nicene Creed of 327 CE, which, among other things, established the divine nature of Jesus as The Christ (see below) and set the official date of Easter. Constantine threw the political and military might of the Roman (later Byzantine) Empire behind the Nicene Creed, and, as a result, for the first time it became possible to “be Christian in the wrong way”. In other words, if you continued to hold beliefs or practice doctrines that weren’t approved of in the Nicene Creed, then you were “doing Christianity wrong”.

Among these “wrong-headed” beliefs and practices were: denying the divinity of Jesus; rejecting the belief in Jesus’ resurrection three days after his crucifixion; and questioning the verity and efficacy of the Holy Ghost as God’s primary conduit of interaction with the physical world. (Later, other attitudes and/or practices that were seen as threatening to the power of the Church (eastern or western) would be denounced as heretical, as would practicing any religion other than some accepted, recognized version of Christianity).

The word “heretic” comes from the Greek word hairetikós, which meant “able to choose”. It came to be applied first to those who resisted the Nicene Creed. Because they were seen as “choosing to do Christianity wrongly”, they were heretics (see the discussion on the word “infidel”, below). The Church used Roman military might (later developing armies of its own) to do its best to stamp out these “willfully chosen, wrong beliefs and practices” and to eradicate the writings upon which they were based.

This, of course, established a precedent that would see some of its worst excesses during the Crusades (between 1095 and 1271) and the Inquisition (starting 1231 CE) — in fact, more than half of the Crusades ordered by the Roman Church were conducted in Europe against people who also called themselves Christians!

Today, the word “heretic” has taken on a more generic sense of “anyone who does not conform to an established attitude, doctrine, or principle,” and is used in secular as well as religious circumstances. For instance, fan-fiction is sometimes called “heresy” when it contradicts the accepted norms and/or history of a given fictional universe (its canon).

Julian the Apostate: Looking Back

The Roman Emperor Julian (Flavius Claudius Julianus; Constantine’s grandson), was born in 331, and ruled the Roman Empire as Augustus from the eastern capital of Constantinople for about 2⅓ years between 361 – 363. Julian was born a Christian and professed the Christian faith (at least publicly) until shortly before becoming Emperor. After his ascension to the throne, he openly embraced Neoplatonic Hellenism and sought to restore widespread pagan worship. Thus, he was called “the Apostate”: apostasy is the condition of having rejected one’s former religion.

He was stridently opposed to the Christianity of his time (he had not had a very positive experience of it). He almost exclusively referred to Christians as “Galileans”, and even wrote a treatise titled Contra Galilaeos (Against the Galileans). The original has been lost, but from references made to it by other writers, we know it focused on the inconsistencies and disagreements between the various Christian sects as the primary reason for restoring polytheistic religion to prominence in the Roman Empire. (The fact that his family was renowned for familial homicide, yet claimed to embrace the peace-loving ideologies of Christianity also contributed significantly to his rejection of the newer religion in favor of the older spirituality.)

Julian’s choice of the name “Galileans” was a reference to Jesus’ purported origins in the Levantine region of Galilee see figure 5.4, where he is written to have spent his childhood in the village of Nazareth (hence the epithet “Jesus of Nazareth”). Some sources claim that the family of Jesus’ Earthly father, Joseph, was centered in Nazareth. Jesus’ birthplace is reputed, of course, to have been the town of Bethlehem, which was the seat of the line of King David (reigned c1010-970 BCE); thus claiming that Jesus was born there meant that that he could also be claimed to be descended from the Hebrew King of a thousand years before. This would mean that not only would he have a political claim to the throne, but centuries of prophecy had also declared that the Jewish messiah (see below) would be born in the “city of David” — thus, it could also be claimed that Jesus was that prophesied “anointed one”.

Julian’s reference to Christians as “Galileans” was derogatory. This insult is in the same vein as the question posed by Nathanael in the biblical Book of John, chapter 1, verse 46, when he was told of Jesus’ origins: “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?”9

From Bumpkin To Sinner

Six emperors later (they tended to go through them quickly in those days) the Emperor Theodosius I (the Great) declared in 382 CE that Christianity was the official and only religion of the Roman Empire; he banned all other forms of worship, and decreed that any-and-all deities other than the Christian God were fictions, “false” gods, and that to worship them was heretical.

As a result, anyone — not just those still living in the countryside — who continued worshiping other gods (and particularly the old Roman gods), was no longer to be tolerated as “quaint”, “backward”, and “naïve”, but to be vilified as “rebellious”, “barbaric”, and “ignorant”.

By definition, to be a pagan was now to be a heretic, as well. A word that had previously simply identified “a worshiper of the older nature deities” came to be applied to anyone who worshiped any deities other than the God recognized by the Roman Church — and you could easily lose your life over it.

Enter The Heathens

Interestingly, the word “heathen” comes from an old Gothic (western/southwestern Germanic) word related to the word “heath”. So, “heathen” seems to have had a similar sense as “pagan”, but referring not just to someone who didn’t live in a town or city, but to someone who came from “a place outside”, in other words, an “outlander”. Thus, by extension, a “heathen” is “a non-believer” (because obviously anyone who wasn’t part of your culture automatically had to have a different religion, right?) The term probably was used by the pre-Christian Germans and Scandinavians simply to refer to those who worshiped other gods, and as such was retained (and slightly redefined) when Christianity took root in Northern Europe in the 700s CE.

Thus, “pagan” and “heathen” both came to be used (largely interchangeably, at least north of the Alps) to refer to non-Christians, and particularly those who worshiped older, more nature-oriented deities, and who were therefore “wrong” in their worship according to Roman Catholicism. They “needed to be corrected”, and would make themselves into heretics if they refused to convert.

Nowadays, of course “heathen” tends to be used disparagingly and/or pejoratively (in religious contexts) to mean “an individual of a people that does not acknowledge the God of the Bible; a person who is neither a Jew, Christian, nor Muslim”, and that leads us to….

Western Infidels

The word “infidel” comes from the Latin infidēlis, meaning “unfaithful, treacherous”. While it has been (and still is) used by Christians to refer both to non-Christians and to those who have renounced their previous adherence to the Christian faith, most Westerners are probably more familiar with its use by some sects of Islam in reference to Christians. In this sense, it is an English translation of the Arabic word kafir, which means “rejector”, “denier”, “disbeliever”, or “unbeliever”.

In Islamic belief, God (Allah) revealed his plan for humankind in three parts, or stages: the Law of Moses (the Ten Commandments, canonically said to have been revealed in the 13th Century BCE); the teachings of Jesus (1st Century CE); and the revelations to Muhammed (7th Century CE).

In this view, Christians, by clinging to Jesus’ message but ignoring the teachings of Muhammed, are being “unfaithful” to God (Allah). They are ignoring the last revelations of Allah’s will, and thereby rejecting his plan for humanity. Islam actually recognizes and reveres Jesus as a prophet, but takes exception to the (post 5th Century CE) Christian doctrine of dyophysitism, which is the belief that Jesus (as the Christ, see below) was (at least partly) divine, and therefore, was “the Word made flesh”, a physical manifestation of God on Earth.

The vehemence of the Islamic official rejection of this idea is evidenced in the inscription around the outside of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem see figure 5.5, which reads, in part: “It is not befitting to (the majesty of) Allah that He should beget a son.”

Jesus (the) Christ

The earliest followers of Jesus did not call themselves “Christians”; indeed, for the first 70 years or so of the movement, they still considered themselves to be Jews (albeit of a new variety), and conducted their worship in the synagogues alongside their more traditional neighbors. Judaism, after all, had prophesied a Messiah (see below) since ancient times — and Jesus’ followers declared that he had fulfilled that prophecy. The name “Jesus”, is, in fact the Latinization (Iēsus) of the Greek Iēsoūs, which is itself a translation of the Hebrew Yēshūa (“God is help”, or “God Saves”). The historical person’s actual name would probably have been Yeshua Bar Yosef (Aramaic) or Yeshua Ben Yosef (Hebrew), both meaning “Yeshua, Son of Yosef (Joseph)”.

Another direct translation of “Yeshua” into English is the name “Joshua”. In fact, in the King James Version of the Old Testament, there exists a mistranslation in which the name of the Hebrew leader, Joshua, is rendered as “Jesus”: “For if Jesus had given them rest, then would he not afterward have spoken of another day.”20

“The Christ”

The word christ is from the Latin Chrīstus, borrowed from the Greek χριστός (chrīstos, “anointed”), which is a conceptual translation of the Hebrew māshīaḥ (“anointed”), and which is directly transliterated into English as “messiah”. It appears in 2 Maccabees, chapter 1, verse 10, in a reference to those who had been anointed (chosen) as priests.

The first (written) use of christ to refer to Jesus appears in the Book of Matthew, chapter 16, verse 16, when Simon (Peter) answers a question from Jesus by saying: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” It then subsequently appears in the first line of the Book of Mark (1:1), which reads: “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.”

Christian

The first use of the word “Christian” to refer to followers of Jesus appears in the Acts of the Apostles, which was probably written between about 90—110 CE, most likely by the same author as the Gospel of Luke, where the passage reads, “… the disciples were called Christians first in Antioch,” which tells us that the term was in common use by at least the end of the first century of the movement.

“Christian” as the name of the followers of Jesus appears only two other times in the New Testament, in Acts 26, and finally in 1 Peter 4. It is worth noting that in the first two instances, the word is used in the sense of others speaking about the followers of Jesus and not the followers referring to themselves using the term.

Modern Borrowings: Pagans, Wiccans, and Druids, Oh My!

(Neo)Pagan

Various groups today refer to themselves as pagans or neo-pagans. In both cases, the speaker is often referring both to a set of beliefs and to a set of practices. Interestingly, though, for many who choose these self-descriptions, they seem to use them more as indicators of what they have rejected than as affirmations of what they’ve adopted. “I am a pagan,” seems more to be the rebellious declaration, “I am not a Christian!” Fundamentally, these terms are used validly only if what is meant by them is the reverence or worship of pre-Christian, nature-based deities — whether perceived as personified or simply as universal forces.

Wicca

Wicca is (not to put too fine a point on it) a completely modern invention, having been developed in the 20th Century and publicized in Gerald Gardner’s 1954 book Witchcraft Today.22 It seeks to position itself as a legitimate successor to older pagan belief systems, but with aspects that tailor it to the specific spiritual, emotional, and psychological needs arising out of the special challenges of modernity.

Druidism/Druidry

In a similar vein, Druidism (Druidry) is largely a modern belief system, though its origins are older than that of Wicca, dating to the 17th Century in Britain. The Ancient Druids, apparently a shamanic/priestly class in Gaulish and Celtic culture, left behind no writings of their own to record or explain their beliefs and practices. While ancient sources do make mention of the Druids, these accounts are almost universally disparaging, and therefore suspect.