6. Interpretation and Exploration of Myths

The scholarly exploration of mythology as an academic subject is fairly young; in the past, consideration of these stories and concepts were generally left to philosophers or theologians.

The academic investigation of mythology must be recognized as an attempt to impose logos on mythos, an effort doomed, if not to abject failure, nevertheless one which will always produce less-than-satisfying results.

Be that as it may, logofying mythos is necessary to some extent in order for students and scholars to have some fundamental common framework in which to conceptualize and discuss the psycho-social antecedents and legacies of this natural and ancient expression of the affective domain of human consciousness.

Areas of Focus

In general, we can categorize the study of mythology into several broad categories, between which there will naturally be overlap and duplication (mythos by its nature does not follow a rigid set of rules).

As A Belief System

One of the first questions that arises when one begins to study mythology is one along the lines of “Did people really believe this stuff?” The answer is difficult to pin down; mythological stories may at one time have been considered historic or scientific fact by the culture which produced them.

This is because one of the primary tasks (desires?) of the human mind is to make sense of the world and of experience, but any explanation developed must necessarily be couched (at least initially) in terms of the data (observations and experiences) available, and the extent of one’s existing “knowledge”.

For instance, ancient peoples looked around themselves and noticed that the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets moved in the sky, while the ground on which they stood “obviously” remained still and stationary (barring the odd earthquake or landslide).

Thus, it was “natural” for them to adopt the view that the Earth was anchored at the center of literally everything, and the rest of the major objects in the universe revolved around it in regular, repeating patterns. Until such time as experience or observation produced data that was inconsistent with this view, there was no reason to question nor modify it.

Observations of the Sun’s journey across the sky defined the concepts of “day” and “night”; records of the Moon’s changing shape as it rose and set in its regular motions encompassed the “month”; notations of which constellations of stars were visible overhead from month-to-month encapsulated the “year”.

Complex-but-useful systems were devised for tracking, recording, relating, and predicting these “heavenly” motions, which were effective in humans successfully keeping track of time and notating the events, large-and-small, which comprised the experiences of their lives, individually and collectively.

A “science” is, by definition, a rigorous, regularized system of observation, measurement, and expression which produces useful and repeatable knowledge and practical applications. The previous paragraph describes such a system. We may know today, as a result of more detailed data of phenomena which was either unknown to or inaccessible to the ancients, that their “geocentric” model of the universe was incomplete and overly simplistic, but in terms of what they “knew” and what they were able to deduce from observation and experience, their view was to them obvious, indisputable fact.1

As Disguised History

Euhemerus of Macedon (c. 300 BCE) and others of like-mind, tried to rationalize the often fantastical persons and events of mythology by promoting the idea that they were distortions or exaggerations of historical fact. This view came to be known as euhemerism and may be summarized in the pronouncement that “all myths have some basis in fact”. While euhemerism is considered to be naïve by some modern mythologists, it nevertheless may have some small merit in exploring how humans record and recall their individual and collective experiences over time, in light of how stories morph and change over countless retellings (have you ever played The Telephone Game?).2

Greek Zeus, for example, may be thought to be based upon ancient oral histories of an early-times chieftain who exhibited extraordinary abilities of both body and mind; who tamed the wilderness; established a settlement; slew animalistic threats to human safety; and cemented assimilations and alliances with nearby groups through political “marriages” to the daughters of neighboring (sometimes rival) chieftains. Euhemerism posits that these noteworthy-but-wholly-human feats became magnified and embroidered over centuries of retellings until the historical Zeus becomes apotheosized into the deific Zeus of the Classical Greek world.

Homer’s account in the Illiad of a long, drawn-out war between the Greeks and the Trojans is often cited as an example of euhemerism: archaeological research and excavation in-and-around the Hill of Hissarlik in modern Turkey has shown that there were several different periods of inhabitation of the area. Noting that “war was common in [the Bronze Age] world,”3 it is entirely possible that some sort of armed conflict (perhaps more than one) occurred between Greece and the inhabitants of that part of Asia Minor.

However, whether-or-not any such conflict between actual chieftain-kings named Agamemnon and Priam historically occurred as the result of the dalliance of a Greek queen named Helen with an Asian prince named Paris is (at present) unproveable.

As Disguised Philosophy Or Allegory

Xenophanes of Colophon (c. 530 BCE) complained that, “Homer and Hesiod have attributed to the gods all the things that are shameful and scandalous among men…,”4 so he and others tried to redeem the gods (and mythology in general) from the taint of immorality by declaring that embedded in these stories were significant truths about the human condition.

This interpretative style is called allegory, said by Ernst Curtius to be “… in harmony with one of the basic characteristics of Greek religious thought: the belief that the gods express themselves in cryptic form — in oracles, in mysteries.”5 While allegory is useful as a vehicle for looking beyond the superficial aspects of a particular myth, it is considered by many to not be a valid pursuit in the exploration of mythology (the Roman Stoic, Seneca, called allegory “foolishness”).6

As Fables Illustrating Moral Truths

The use of fables to illustrate moral truths or social norms is an ancient practice, employed by sages such as Aesop, Jesus of Nazareth, Nasreddin, and Hoshi Shin’ichi. During the European Middle Ages, in order to retell pagan stories without falling afoul of the Church, translators, artists, and philologists asserted that the tales illustrated moral truths which were in accord with Scriptural teachings.

Aesop’s story of a shepherd boy who breaks the monotony of watching over his flock by raising false alarms about the presence of a predatory wolf (and is ultimately ignored when a real wolf presents itself), is typical of this type of tale, ending with the moralistic declaration “Nobody believes a liar even when he is telling the truth.” This simplifying of mythical stories, however, suffers from a tendency to focus on only one aspect of much more complex and insightful revelations.

As Allegories Of Natural Events or Pre-Scientific Explanations

Obviously, at least some ancient deities were associated with natural phenomena: Zeus and Thor were gods of thunder; Apollo was a god of music (among many other things); Amaterasu was the Japanese goddess of the Sun; Bea was goddess of the wilderness for the Akan people of Africa. This is related to the Cosmological Function (see below).

The earliest human expression of experience with nature manifested in animism, which is the religious belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Animism predates any form of organized religion and is said to contain the oldest spiritual and supernatural perspective in the world. It dates back to the Paleolithic Age, to a time when … humans [survived by] hunting, gathering, and communing with the Spirit of Nature.

Humans had begun to recognize that their own behaviors were guided by conscious choices; it was natural to assume that any action or event in nature must also be guided by conscious choice. Thus, it was reasoned that a stream did “stream-things”, because that was its nature and it chose to behave according to its nature. This was a simple, but practical, way of explaining the caprices of nature. Question: “Why did the stream overflow and flood my garden?” Answer: “Because it is in the nature of streams to do such things.”

An important point to note here is that animism doesn’t presuppose an antagonistic relationship between humans and nature — or between the various objects, creatures, and/or events in nature. A flooding stream does not uproot a tree because it feels animosity toward the tree; the stream was just doing “stream-things” and the tree happened to be “in the way.”

This viewpoint led, however, to more theistic views, in which the various aspects of nature were believed to be caused and/or controlled by independent, individual entities who brought about natural events because of some conscious will to achieve some goal. This shifted the thinking. Question: “Why did the stream overflow and flood my garden?” Answer: “Because the stream god caused it to do so.”

This, inevitably, leads to a further enquiry: “Why did the stream-god want to flood my garden?”, which can be answered in any number of ways, giving rise to a system of aetiology, or “the study of causes”, which, in turn, often transforms into some sort of dogmatic religious view and/or practice.

This interpretive model also helps to codify why natural processes seem to behave according to invariable rules: a dropped object falls to the ground, a hot object causes burns, rain makes things wet, etc. If such rigid rules exist in nature, and all events are caused by a conscious will in action, then it follows that the rigid rules of nature have been decreed and are enforced by at least one conscious will — a god.

As Charters For Customs, Institutions, or Beliefs

This aspect is related to the Sociological Function. In this interpretation, myths are not simple explanations for natural objects and events, but rather explications which authorize and validate social customs and institutions. One of the benefits of this interpretive model is that it seeks to explore how a story functions in a society more so than as an explanation of a phenomenon.

Many myths serve this purpose. The Sumerian story of Atrahasis and the Flood serves to explain social stratification and division of labor when it depicts “lower class” gods rebelling and leading to the creation of humankind to do the “grunt work” in the world. The biblical tale of the Tower of Babel explains why different groups of people speak different, sometimes mutually unintelligible, languages.

As Religious Power And Explanations of Religious Rituals

This is also related to the Sociological Function, and is something of a refinement of the above, in that the “natural order” of the universe comes to be seen as a sacred decree, apprehended and explained by a priesthood of individuals who (for a variety of proffered reasons) have been given privileged access to the will and motivation of the god(s).

The universe must continue to function smoothly; to do so, the god(s) must be kept in a positive relationship with humanity; the maintenance of this congenial relationship depends upon humans giving the god(s) their due deference and devotion.

When a drought occurs, those who (claim to) know the will of the god(s) declare that there is divine dissatisfaction with humanity, and ordain certain rites and ceremonies to alleviate the animosity. The average person is doubtless aware of the drought and its consequences, but has no clue as to its cause nor its remedy.8

Thus, the temples must be maintained, so that worship may continue, and those who tend the temples and interpret the will of the gods must also be free to apply their undivided attention to caring for the temple and communing with the divine. Because these duties demand their full time and attention, they cannot provide for themselves the necessities of life, such as food, drink, clothing, etc. The rest of society must ensure that the priesthood has all of the basic necessities, as a sort of “salary” to the clergy for their invaluable work in keeping the lines of communication open between Heaven and Earth….

As Psychological Archetypes And Models Of Social Norms

Mythology can be viewed as an early variety of what in the modern world became the sciences of psychology and sociology. In his work as a therapist, Carl G. Jung (1875 – 1961) noted that certain common images and/or symbols would frequently appear in the dreams and/or fantasies of his patients.

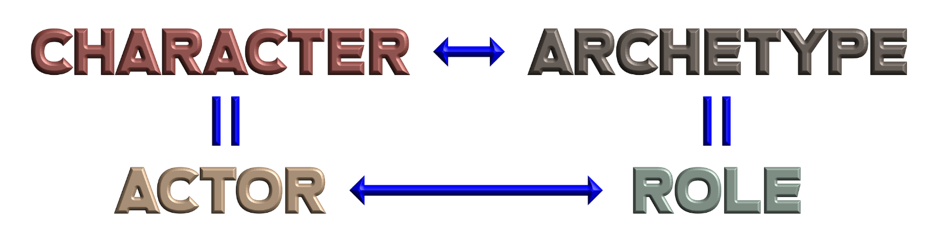

He came to the conclusion that these motifs and themes must represent some sort of “… myth-forming structural elements … in the unconscious psyche.”9 He named these archetypes (<Latin archetypum an original <Greek archétypon a model, pattern (neuter of archétypos of the first mold, equivalent to arche- + týp(os) mold, model).

Jung posited that many such archetypes exist; the Father — the authoritative power; the Mother — the nurturing energy; the Shadow — the parts of one’s personality which conflict with the way one believes they should feel and behave; and many, many more.

A society is nothing if not a collection of individuals. Thus, similar behaviors in which large numbers of individuals engage become the basis of “social norms” — beliefs and behaviors expected and demanded of the individual by their society.

Hence, some archetypes evolve which exemplify which behaviors are approved of and encouraged by the collective, and which are disapproved and discouraged — and what rewards and punishments an individual can expect in consequence of engaging in either type of behavior.

As Simple Stories

The simplest (and perhaps least helpful) interpretive model is that myths are just stories, intended for entertainment and escapism, and any deeper meaning is assigned to them individually and/or collectively by the audience, irrespective of any possible intention upon the part of the author/originator.

Is it possible that the originator did not consciously seek to embed a “deeper meaning” into the story? Certainly! Is it possible that they created a story which has no deeper meaning whatsoever? Certainly not! Given that all communication is manipulation,10 and that each person functions from unconscious biases about the world and their personal experiences in it, to say that no story ever contains a subtext is … well … naïve at best, and delusional at worst.

Therefore, it is worthwhile and valuable to examine a story in terms of its authorship, the culture/society in which it was created (and at what point in that community’s history it was created), to attempt to identify any “hidden biases” the originator may have unintentionally included and to reason out what predicated those biases.

Additionally, examining a story for the symbols and metaphors which it engenders in a modern audience — and thence to ferret out possible unconscious modern biases, is an invaluable exercise. It allows the modern consumer of the tale to become more self-aware; through a deeper understanding of their own worldview generated both through dissecting its nature, and through comparing it to possible other worldviews by recognizing that others may view a given metaphor or symbol in a completely different context.

Joseph Campbell And His Influences

Carl G. Jung (1875 – 1961)

A student of Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939), Jung’s work in exploring dream symbolism is most relevant to our study of mythology. As mentioned above, Jung postulated the archetypes, which he held to be traditional expressions of collective symbols appearing in the dreams of members of a given society. He believed that these had developed over thousands of years, and had become a sort of library of symbols on which a society came to depend for its shared worldview.

For instance, the image of a dog in many Western cultures came to be symbolic of trust, faithfulness, dependability, protection, etc. Hence its appearance in literature and visual arts often carried more meaning than simply that of the animal, itself. However, Jung also thought that these symbols could come to be heralds of common behavior patterns or inherited schemes of functioning within the society, in much the same way the bear and the bull are used today to refer to different functioning modes of the stock market, or the donkey is used to represent resolve (sometimes to the point of stubbornness), or the elephant to refer to clinging to the past (due to their reputed long memories).

The Structuralists

Structuralism is a general theory and methodology of culture studies, which holds that human cultural expressions must be understood in relation to their interaction with broader socio-cultural systems. In seeking to discover the structures that underlie all human activity and expression, it thus combines the study of human societies with psychological theories. For our purposes, this allows the study of the origins of mythic systems in terms of the minds of individuals, the fundamental elements of culture and society.

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908 – 2009)

Strauss’s basic assumption was that all human behavior is based on universal, unchanging patterns, and he held that these patterns are the same in all societies and all historical ages. From this, he contended that no one version of a myth is the “right” one; each retelling is relevant to the time and circumstances in which it is being shared.

Vladimir Propp (1895 – 1970)

Propp posited that character types served various roles within a myth, expressed through their actions, and that the functions and their associated actions are more important than the actual character to which they are attributed in a myth. Thus, he developed the idea of a “motifeme”:11 a basic, reusable building block of mythological symbolism that can be assigned to any character in a story at any time, as needed to move the story forward.

Walter Burkert (1931 – 2015)

Burkert asserted that each successive generation retains the culture’s mythology, but interprets it according to its own particular circumstances. Thus, he held that while myths have a historical “dimension”, they develop over time with each successive layer of interpretation and application.

Joseph Campbell (1904 – 1987)

Joseph Campbell’s work was both synthetic and pioneering.

The Monomyth

In terms of original thought, Campbell was the first to promote a universalist view of mythology. Before Campbell, most scholars of mythology restricted their studies to Graeco-Roman mythology (with the occasional foray into Celtic or Norse myths), but largely discounted or ignored the mythologies of other cultures.

Borrowing the term “monomyth” from James Joyce, whose work Campbell studied extensively, he realized — first through his study of heroic myths — that no matter the origin, the language, the setting, or costuming of mythological stories, when reduced to their basic message, the content was always the same.

From this, he recognized that mythological symbols were universal, a fundamental expression of the human experience. While their superficial differences made them vital examples of the marvelous breadth of human experience and expression, acknowledgement of their fundamental commonalities erased “Othering” and Eurocentrism from mythology and the formal study of it.

Later, he came to realize that this was applicable to any archetype, not just the Heroic. The Mentor is the Mentor, the Damsel is the Damsel, the Trickster is the Trickster; the language they speak, the costume they wear, the environment in which they act is an expression of the beauty and variation of humanity, but their stories are recognizable and relatable across socio-cultural divides.

In terms of synthesis, he adopted and adapted concepts from the work of Jung and the Structuralists to form the superstructure of his description of the place of mythology in human culture and society. From Jung, Campbell borrowed the concept of the archetypes, declaring them to serve in mythology as a “… vocabulary in the form, not of words, but of acts and adventures…”12 which comprise “…a certain typical … sequence of actions, which can be detected in stories from all over the world, and from many, many periods of history…”.13

This is also related to Propp’s “motifemes”; the archetypes and their characteristic actions form basic, reusable building blocks that can be inserted whenever and wherever needed into a mythical story to empower it.

This is Campbell’s monomyth; the recognition that all of mythology is a ubiquitous human expression across all cultures and throughout all time, differing in the particulars of each presentation but universal in substance. The archetypes never change, but their manifestations across different cultures do.

Also, Campbell realized that the archetypes are assigned to characters in much the same way as actors take on roles in plays and movies.

Harrison Ford, for instance, has been Han Solo, Indiana Jones, Bladerunner Rick Deckard, President James Marshall, Jack Ryan, Dr. Richard Kimble, etc., but off the set, away from the cameras, he is always-and-forever Harrison Ford: actor, husband of Calista Flockhart, human being.

Similarly, Thor is a son of Odin and one of the Æsir, the Norse Warrior Gods who inhabit Asgard on the highest tier of the material universe. This aspect of the character never changes. Yet, while Thor generally assumes the mantle of the Heroic archetype, he may just as easily fulfill the role of Mentor, if doing so best serves the story at a given juncture.

This is also more reflective of actual human experience; no person behaves the same way in all circumstances. Sometimes, you provided comfort and guidance to a friend; other times, you receive the same from them. You are not the same person at Sunday dinner with your grandparents as you are on a Saturday night out with your friends.

The power of this aspect of the archetypes is that it necessitates a deeper interaction with the myth on the part of the audience; just because Hermes has made an appearance, don’t automatically assume the Trickster is present — watch closely how Hermes behaves: the nature of his actions will tell you soon enough which archetype he is manifesting.

Mythic Relevance and Crystallization

From Claude Lévi-Strauss Campbell accepted that no one version of a myth is the “correct” one, and combined this with Burkert’s “historical dimension” of mythology . Myths must, Campbell said, provide models “… appropriate to the possibilities of the time in which you’re living.”14 If a myth is not readopted and reinterpreted by each succeeding generation, but instead “… gets stuck to the metaphor, then you’re in trouble.”15

The myth crystallizes when it is considered by society that it must always be retold and understood in its original context, even when that context is no longer relevant or helpful to the individual or society. At this point, the myth ceases to serve you, but rather “…begins to dictate to you”16 how you should live your life, instead of describing “… the rapture of being alive … so that the life experiences … on the purely physical plane will have resonances within [to] … innermost being and reality.”17,18

When a myth (or, indeed, any ideology) crystallizes, it becomes frozen, rooted to a certain form of expression, a certain role within socio-cultural consciousness (though it may provide a window into past ways of thinking and behaving), it no longer serves to explain or validate a society’s current worldview.

In summary, Campbell’s structure for understanding comprises four elements:

- Archetypes: Symbols which are fundamental to human psychology, regardless of cultural distinctions.

- Universality: The equivalence of mythological expression; human psychology is always the same, regardless of historical age or cultural conditioning.

- Flexibility: Myths generally, and archetypes specifically, form a vocabulary of situations and actions; characters portray “standardized” roles which are more important than the character performing the action.

- Relevance: Myths which are not renewed and kept relevant by each succeeding generation “crystallize”; they cease to be useful to the culture, and may – in fact –become harmful to further positive social development.