2. Fundamental Concepts

As with any discipline, a shared vocabulary is necessary for effective communication, so let us start by exploring some vital terminology.

Epistemology

Epistemology is, broadly, the theory of knowledge, and it is a major subset of philosophy. It is relevant to our study of mythology in the guise of the question: “How do we know what we know?” For our purposes, knowledge (and how it is acquired) can be largely divided into two types, described by the Latin terms a priori and a posteriori. These terms and concepts are of central importance to the study of mythology.

The term a priori is Latin for “from the previous”, or “from the one before,” and references knowledge held to be true but which is not based on experience or observation. In this sense, a priori describes knowledge that requires no evidence. This kind of “knowing” can be thought of as “knowledge of the heart”, captured in terms like “intuition” and “instinct”.

In contrast, a posteriori — Latin for “from the one behind” — is knowledge based on experience, observation, and data. The veracity of such knowledge is considered to be true based on the quality, frequency, and repeatability of these sources. Thus, a posteriori knowledge requires not only evidence, but demonstrable, repeatable data collection. So, this kind of “knowing” can be conceptualized as “knowledge of the mind”, captured in terms like “science” and “research”.

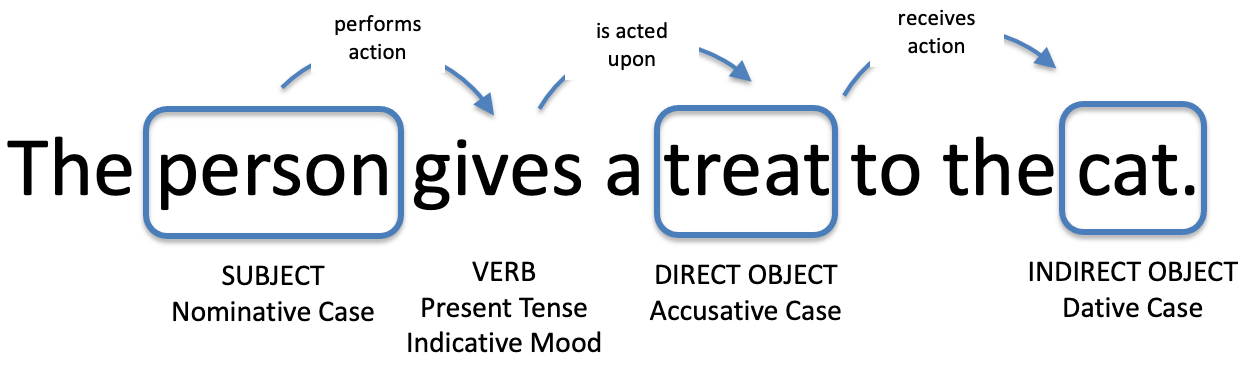

These terms, then, are related to two ways of describing reality and the experience of it: subjective and objective see figure 2.1. Here, an example from language studies may be helpful. In the sentence, “The person gives a treat to the cat,” the subject of the sentence is the noun which refers to the person or thing engaging in the action referred to by the verb. Here, “person” is the subject noun, referring to the individual engaging in the action of giving (“gives”). The object of the sentence is the noun which being affected by the action described by the verb: here, the object noun is “treat”. It is the thing which is being given by the person.1

Objective reality (what Immanuel Kant called “noumena”),2 then, is the reality of the object; the objects and events which occur as a result of the normal, natural processes of nature, and which do not require the presence of an observer to be “real”. Objective reality can be related to content and denotation (see below).

In contrast, subjective reality (Kantian “phenomena”), is the reality of the subject; if you will; it is the “internal” reality, comprising both experience and the reaction to it. This reality can only be “real” in the sense that a consciousness is interacting with it. This can be associated to context and connotation (see below).

Content and Context (Denotation and Connotation)

Content is denotative; it is explicit, descriptive, objective, concrete. The word “apple”, for instance, is simply that: a word which refers to a particular variety of fruit. From a content perspective, it doesn’t matter what variety the apple is, nor does its size or color matter. “Apple” is “apple”, nothing more and nothing less; “egg” is “egg”; “dog” is “dog”, and so forth. In the denotative sense, an apple (or an egg, or a dog) exists, whether or not it is being interacted with by another object. Its existence is not dependent upon anything else.3

Context is connotative; it is implicit, conceptive, subjective, abstract. In terms of context, “apple” can “stand for”, “imply”, or “suggest” more than itself. The word “apple” expands from being a thing-in-and-of-itself into being more of a sort of container for ideas and concepts. It serves as a sign, a symbol, an implication, or a signification.

For instance, an apple shape with a crescent cut out of it represents a particular technology manufacturing company and the products it makes; an apple on the cover of a book about nutrition implies health and vitality; an image of a basket overflowing with apples might suggest abundance, affluence, prosperity, etc.4

However, none of those concepts are inherent in “apple” itself; they are neither an intrinsic part of the word “apple”, nor are they realities that “come out” of a physical apple — the fruit does not produce cell phones or magically bestow physical well-being: just being in a room with an apple doesn’t make you healthier.

The awareness of (and distinction between) content and context, denotation and connotation, is central to the effective study of mythology. When an owl appears in a myth, for example, is it intended to simply refer to a bird of that particular species, or is it a symbol (metaphor) for wisdom? Is a book just a book, or is it a sign of knowledge?

Think of the ubiquitous Hammer-and-Sickle (see figure 2.2): this icon carries meaning, signifying the unification of the industrial working class (represented by the hammer), and the agrarian peasant class, represented by the sickle (scythe), as the source of political/economic power and governance in a communist society. It is still the central motif of many political parties around the world, although it no longer appears on the flag of any major nations.

Further, if the object in question is being referred to connotatively, which connotation applies? The answer to that question depends on a number of factors: Which society/culture is using the symbol? Which segment of society is employing the symbol? At what time in history is the symbol being employed (e. g. a chain may at one historical point represent strength and unity, but at a different time refer to slavery and oppression).

Context and connotation are where the fun is: in Kant’s view, only phenomena comprise subjective experience, and phenomena are a result of our various sensory organs and processes reacting to stimuli impinging upon them as a result of the existence and actions of objective reality.

Thus, for Kant, context (subjective reality) is constructed by consciousness in every moment from four components: 1) the influence on our sense organs of external objects and events (objective reality); 2) our impressions (reactions) to being affected by objective reality; 3) our memory (recollections of past instances of being affected by objective reality; and, finally 4) our imagination — the ability to conceive of a significant connection between objective reality and ourselves.

In simpler terms, we recognize, organize, and categorize (i. e. contextualize) the data of our sense impressions to create meaning. Think about the sheer power of this statement: it forces us to realize that meaning is never inherent in the object. “Things” just are. Their meaning is only and entirely assigned to them by us. This is a crucial awareness for the study of mythology.

Consider the Mona Lisa painting by Leonardo da Vinci figure 2.3. It is currently housed in the Louvre Museum, in Paris, France, where it hangs on a wall behind several inches of plexiglass and is visited and viewed by millions of people every year.5 It is considered one of the greatest works of art produced by human beings in the entire history of our species up to this point.

And yet, if every human being were to vanish from the face of the Earth tomorrow, the Mona Lisa would still be hanging on the wall of the Louvre, and it would mean nothing. Any-and-all meaning it has is assigned to it by consciousness, in the absence of which, meaning is non-existent.

Further, think about what a painting actually is: it is ground up matter (pigment) suspended in a liquid (called a “binder”) and applied to a surface (e. g. canvas, board, plaster, paper, etc.) in a particular arrangement (composition).

The Mona Lisa is a painting; but, so is a child’s effort from their preschool art lesson. Does one have more “meaning” than the other? If so, why; if not, why not? What determines the difference in the meaning of the two? Is the meaning of each the same for everyone, and, thus, universally acknowledged? Is there an objective scale upon which the meaning of each can be located, in order to determine a corresponding “value” of each?

The wonderful (and sometimes infuriating) thing about context/connotation is that it is the result of a choice, and choices can be reexamined, reevaluated, and revised. Not only is meaning not inherent in the object, it is not permanent, but fluid and dynamic. In answer to the posing of the question about an artwork, “What does it mean?” the Zen master would stoically reply, “You make an incoherent noise.” The question has only a subjective answer, and therefore asking it of anyone else is a futile act.6

Logos7 and Mythos

We will encounter these two terms frequently during our exploration of mythology, so it is worth taking a few lines to introduce them.

Logos: the Greek root of the word “logic”, lógos mans “a word, saying, speech, discourse, thought, proportion, ratio, reckoning”, and comes ultimately from the Greek legein, meaning “to speak”.

Logos is rational, pragmatic, scientific thought. Note that the root of the word “rational” is “ratio” and a ratio is a mathematical relationship. For instance, if you have two apples and one orange, the fruits are in a mathematical two-to-one ratio. If you were to increase the number of both apples and fruits by a factor of three, you would then have six apples and three oranges (6:3), but this is still a two-to-one ratio. Bearing in mind that “logos” is related to “ratio” helps us to remember that it is the word for formalized, regularized, quantified thinking and expression.

Logos is seen as the foundation of Western culture, beginning with Greek explorations into geometry and philosophy in the 6th Century BCE, and formalized as a doctrine during the European Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th Centuries CE. Modern science is predicated upon the concept of provability and repeatability, codified by René Descartes in the Discourse on the Method (1637).

In modern science, for something to be considered a fact, the source of the information must be identified as reliable, accessible to anyone seeking it, measurable and quantifiable, and subject to consistent repeatability via structured experimentation.

In this sense, logos is intricately connected to objective reality (Kantian noumena): the things to which facts relate are believed to have an existence independent of the observer and/or experimenter, and thus be free from what Roger Bacon called the “Idols of the Tribe”8 (idola tribus) – the variability of individual experience which make human perceptions unreliable as proofs of reality.

A room that feels warm to me may feel cool to you; however, a thermometer on the wall would indicate a single temperature (in whatever scale to which it is calibrated), for instance 74° Fahrenheit. The temperature indicated on the thermometer is not a matter of personal experience nor of personal preference; it is an objective fact, not subject to debate, and independent of the perceptions of any of those in the room.

Robert Pirsig, in Lila: An Inquiry into Morals, wrote that “Scientific truth has always contained an overwhelming difference from theological truth: it is provisional.”9 What he meant by this is that the aim of scientific exploration is to continuously update human knowledge with new information.

It is not that what we “know” today is “wrong”, but it is expected that it is incomplete. However much we know about a phenomenon, the scientific assumption is that there is always more to know — more to discover. There are entire institutions, called research universities, whose purpose is to reveal that what we currently know is only part of the whole picture.

While this means that our knowledge is constantly growing and expanding, it also means that we are by no means certain about anything related to objective reality. Thus, the common aphorism reminds us that “change is the only constant.” As Jack Fraser says in an online article at Forbes magazine:

However, though an experiment may be repeated a million times by thousands of experimenters and all of the results are always the same — there always remains a chance that a future instance of the experiment may return a different result. While no theory can be proven, all theories can be disproven, by a single experimental result that contradicts all other results, no matter how many there have been. Evidence and experimentation can bring you statistically closer and closer to the likelihood that you have discovered a fact about the universe, but that statistical likelihood can be demolished in a single experiment.

This means that in modern, science-oriented societies, certainty is impossible. However, this is psychologically uncomfortable for human beings. We like to be able to at least tell ourselves that we are certain about some things; that some knowledge can be relied upon to always be true; that some aspects of life are dependably predictable.

This is where mythos comes in.

Mythos: The ultimate origin of the word “mythos” (Gk. mȳthos) is unknown, which seems utterly appropriate for a word that encapsulates the awareness of and appreciation for the “…mystery that underlies all forms [which is] beyond all categories of thought.”11 In ancient Greek, it came to mean “speech”, “thought”, or “story”, and it is this last definition which connects it to the storytelling aspect of mythology.

Mythos was regarded by the ancients as the primary means of acquiring knowledge. This makes sense; mythos, being associated with mystical and spiritual existence is about experience. All conscious creatures interact with the objective (noumenal) reality in which they find themselves, and we call those interactions “experiences”. Poke an amoeba with a pin and it will move away from the irritating stimulus.

Human beings were having experiences long before we started thinking about and attempting to analyze those experiences. Think of it this way: a dog having a fear reaction to thunderclaps isn’t asking itself12 “What is that noise? Where is it coming from? Why is it making me afraid?” It is simply afraid, and seeking to escape the thing or the environment it is associating with that fear. It is the same with the amoeba; it finds the poking sensation unpleasant, so it moves to avoid it – but it is not cogitating on the source of the poking, and it certainly isn’t coming to any judgements about itself in relation to having experienced a poking sensation.13

Human beings, on the other hand, are capable of asking those sorts of questions (and we do), and of judging ourselves and each other in relation to the experience. That is what led to the development of logos in human consciousness; but, originally, we simply reacted to fear stimuli in the same way the amoeba or our family pet does today.

Hence, mythos represents the primary means of acquiring knowledge because it relates to non-contextualized experience, which Gary Zukav says, “… is not bound by [logos] rules … it is more real.”14 It is concerned with the timeless and constant in existence. While fear of a particular thing or situation may pass, fear, itself, as a form of reaction to noumenal reality antecedes any specific species of fear, and remains as an option for future reactions. Getting over a fear of thunder does not automatically “cure” a fear of snakes.

In modern English vernacular, “myth” is often used as a synonym for “false”, or “untrue”; as in: “Don’t believe that – it’s a myth.”15 This is not the sense in which the word is used here. In our study of mythology, a myth is a story which expresses an a-historical, universal truth about human experience. The word “a-historical” means “outside of history”. While a myth may be set in ancient Greece or India, the message it carries about human experience is not particular to the specific culture. Referring to the above discussion about fear: all human beings feel primal fear of certain stimuli (the unknown, violence, etc.) — there is not a “Greek version” of primal fear which is in some way different from an “Indian version” of primal fear.

This is where myths differ from other folklore such as fables, fairy tales, etc. In the latter, the specific milieu (setting) of the story is relevant to the message the audience is expected to understand from it. For instance, an Inuit story about a trouble-making polar bear would make little sense to a Tuareg tribesperson of the Sahara desert. But, a story about a camel with a bad attitude would also make little sense to the Inuit. Whereas a story about another person making mischief would be easily understandable to both.16

This also highlights that mythos-truth is of a different species than logos-truth. For instance, Herodotus wrote a history of Greece which was based upon Greek mythology and the epic poetry of Homer dealing with the Trojan War and its aftermath — events which (if they were even actual historical happenings) occurred hundreds of years before Herodotus’ own lifetime. In contrast, Thucydides wrote an account of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta — in which he had personally taken part.17

Thucydides wrote about things he personally experienced, or, if he had not been present at a particular battle, he gathered information from people who had been there. The unreliability of eyewitness evidence notwithstanding, Thucydides at least attempted to write a logos-based history, founded upon known, verifiable facts which were devoid of personal, emotional coloring. In contrast, Herodotus wrote a mythos-based history which was composed entirely of oral history, mythology, and traditional tales.

This is not to say that Herodotus’ history wasn’t true. In its way, it was a genuine expression of how the Greek people of his time saw their place in the world and their relationship to it. It was “true” in that it accurately described how the Greeks saw themselves — the fact that others very probably had a vastly different view of Greek culture and its importance in the world has no real relevance.18

Thus, mythology is concerned with the significance of life, its context rather than its content. A myth about a person building a house is not an instruction manual for building a house. It is an account of what being able to build and live in a house rather than crouching in a natural cave, means to the person (and, by extension, to all human beings).

The house is symbolic of intelligence, knowledge, ability, independence, the power to manipulate the material of the natural world to suit one’s own needs and desires, “… turning outer nature into your service.”19 It is about how being human is different from being, say, a bear, and how that different experience causes humans to see themselves in relation to the world around them. This brings us to a discussion of context and its relationship to culture.