4. From Spirituality to Religion

Animism

Animism is the religious belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence.

Animism predates any form of organized religion and is said to contain the oldest spiritual and supernatural perspective in the world. It dates back to the Paleolithic Age, to a time when … humans [survived by] hunting, gathering, and communing with the Spirit of Nature.

“All things speak of Tirawa.”

Let’s look at those emphasized terms for a moment.

Spirituality

Spirituality is considered to be a subjective experience of a sacred dimension, often in a context separate from organized religious institutions, such as a belief in a supernatural (beyond the known and observable) realm; a desire and quest for personal growth; a search for an ultimate or sacred meaning; or, an encounter with one’s own “inner dimension”.

Spirituality is, thus, an expression of one’s awareness of the vastness of existence, a recognition of the limits of personal perception and experience, all-the-while acknowledging the human desire and ability to have a broader and a more complete experience of life.

The Supernatural

For our purposes, the definition of “supernatural” that most applies is … “unexplainable by natural law or phenomena.” Which is to say that science (natural law) can’t measure it, nor reproduce its effects in a laboratory; it’s a valid distinction, but not an exclusive one.

Relating Spirituality to Everyday Life

So, early humans recognized their connection and relationship to the world of natural phenomena, such as rain, wind, the heat of the Sun, etc. These things were understood to be beyond human control, yet they had a significant effect on human life and survivability.

Also, most of the animals they hunted (and competed with for food and for shelter) were abled in ways that exceeded human capabilities. Bears, mammoths, and wooly rhinos were larger, heaver, and stronger; deer and rabbits were faster and more agile; birds could fly; fish were slippery and cunning about avoiding capture.

Early humans also recognized their impact on their environment, even while acknowledging their helplessness in the face of some natural phenomena. If a tribe arrived in one of their regular foraging areas only to find that another tribe had been there first, there might be little-or-nothing left to forage. Every deer brought down was one less that would be available to hunt later. Bringing down a doe which was still nursing her fawns actually killed several deer with one arrow.

In addition, there was doubtless an awareness that the animals they dealt with acted out of some sort of conscious motivation. They went where the food was most plentiful and they avoided areas where they might become victims of predation. They had a recognizable level of consciousness, and they made choices by the use of this faculty.

It was a short step, then, to attributing conscious motivations to non-living natural phenomena (or to view these phenomena as having a sort-of life of their own). Events like the blowing of the wind, the flooding of the stream, the eruption of the volcano, seemed to behave with conscious volition even if the motivations of these things were capricious and sometimes apparently malicious toward humans. So, all things had spirit and were thus all connected by this commonality, even if motivations and goals were sometimes at odds or inscrutable.

However, it was also obvious that sometimes another person’s actions could be altered through interaction; by force, by appeal to reason, by supplication. If the other person were bigger, stronger, and (perhaps) meaner than you, soon enough you learned that you probably weren’t going to get them to change how they behaved toward you by being aggressive back toward them — they’d just pound you into the ground. But, perhaps if you appealed to their humanity, explained how their behavior was harming you, their heart might soften and your interactions with them might become less onerous. It wasn’t guaranteed, but it was better than submitting to abject victimization.

If, then, you attribute conscious awareness to all things, and some things can certainly be influenced in your favor by interaction with them, then perhaps other things can also be influenced in the same ways. So, you begin trying to explain to the Sun, the wind, the rain, the volcano, how their behavior affects you, in the hopes that they’ll aid you or at least try to avoid damaging you in the future. Conversely, perhaps explaining to the sky that rain is needed will encourage it to provide the necessary precipitation for your crops and your herds.

This leads to a new view …

Theism

Theism (literally, the Greek word θεός “theós”, “god”) is broadly defined as … “the belief in the existence of a deity or deities.”

For our discussion, it was applied in either of two ways: pantheism and panentheism.

Pantheism

The word pantheism comes from the Greek terms πᾶν, “pân”, meaning “all, of everything” and θεός, “theós”, meaning “god” (in the generic, non-gendered sense). Broadly, it is defined as:

Pantheism, thus, asserts that “all is divine”; there is no separation between the engendering, motivating divinity and the creation. This is distinct from animism in that animism only attributes spirit and consciousness to all things, but everything is mundane and mortal; whereas pantheism sees all things as divine, having or participating in a nature which transcends the material world.

Panentheism

In contrast, panentheism, from the Greek terms πᾶν, “pân”, meaning “all, of everything”; ἐν, “en”, meaning “in, within”; and, θεός, “theós”, meaning “god” (again, in the non-gendered sense), is the belief …

So, in panentheism, divinity is viewed as the soul of the universe, the universal spirit present everywhere, which at the same time “transcends” all things created.

Thus, panentheism claims that divinity is greater than the universe, such that the universe is contained within divinity, though not separate from it. All things participate in divinity, but no manifestation nor any phenomenon is sufficient in-and-of itself to define divinity.

These views give you new options in dealing with the natural world: You cease to view the stream as an unmotivated natural phenomenon, behaving according to its inherent and capricious nature, with utter indifference to your needs and cares. Now, you assign it a personality, perhaps as an aspect of the transcendent divine which is the origin and foundation of the entirety of existence. Thus, you now see the actions of the stream as certainly due to conscious motivations — motivations which can, perhaps, be altered by interaction.

The stream, now, no longer floods because “that’s just what streams do sometimes”; now, it floods for goal-oriented reasons of its own. Perhaps it seeks to control more land area (a goal you can certainly identify with); perhaps its goals are completely foreign to you. But you believe that it has real goals, and you know that goals are achieved through actions, which are, themselves, stimulated by choices.

And choices can be altered.

Thus, if you can appeal to the spirit of the stream in such a way that it is willing to take pity on you, then you have a chance of influencing it into behaving in ways that are more beneficial to you.

The downside to this development is that it rapidly grows very complex. In this worldview, every stream has its own personality, its own motivations, its own goals; and those of one stream aren’t necessarily identical (or even related) to those of another stream. The wind on the prairie need not be driven by the same goals and motivations as the wind in the forest. After all, don’t some winds blow out of the east and others come from the north, south, or west?

This puts you in the difficult position of needing to learn the peculiar oddities of each and every stream, tree, boulder, mountain, etc. with which you interact. It’s difficult enough figuring out how to get along with everybody else in your tribe, without adding in the effort of getting to know every other thing in the universe on a personal level! You try assigning this duty to the chief or the shaman, but they don’t always seem to get the job done. Your dwelling still collapsed under a landslide.

You need to simplify, so you invent …

Polytheism

Broadly, polytheism (Greek πολύ “poly” (“many”) and θεός “theos”, “god”) is simply the belief in many deities. In practice, it comes in two varieties: hard polytheism and soft polytheism.

Hard Polytheism

“Hard” polytheism is the belief that deities are distinct, separate, real, divine beings, rather than psychological archetypes or personifications of natural forces. Hard polytheists reject the idea that “all deities are one deity.” In addition, they do not necessarily consider the deities of all cultures as being equally real, a theological position formally known as integrational polytheism or omnism.

Soft Polytheism

“Soft” polytheism, in contrast, holds that deities may be aspects of only one divinity; that the pantheons of other cultures are representative of one single pantheon; that they are simply psychological archetypes; or that they’re personifications of natural forces.

Historically, it appears that “soft” polytheism developed first, in the sense of seeing natural forces as personified by deities, with distinct, influenceable personalities. Thus, your neighbor may have a different name or personification for the “spirit of the stream”, but you still recognize that it is the spirit of the stream, with the same motivations and goals as your spirit of the stream.

But you still have the problem of every stream you encounter having a separate spirit. So, you simplify further. Instead of every stream in the world having a separate spirit that drives it, you now posit a single consciousness that defines and describes all streams. This consciousness may be embodied or incorporeal; it may reside in a particular location, or inhabit a transcendent, spiritual realm, but this “deity of streams” encompasses all aspects of “stream-ness” or “stream-hood”.

All streams behave in the same general ways, because this “deity of streams”, a singular entity, embodies and motivates them all. The differences in their behaviors are due to the deity’s individual reactions with the particular circumstances and environment of a given stream. But most of the time, it appears, the deity just leaves all the streams to do “stream-things” on their own, and only manipulates them for particular reasons in specific circumstances.

This, then, transforms over time into “hard” polytheism, in which the “deity of streams” no longer is seen as simply personifying the characteristics and behaviors of streams, but is a separate, unique being, part of whose “job” it is to oversee the performance of streams. And, then, you can simplify still further by extending the influence of the deity to encompass all bodies of water, so that now it is the deity not just of streams, but of rivers, lakes, seas, and oceans, as well. These various bodies of water become, as it were, machines which the deity tends, but which are not intrinsically connected to the physical being of the deity, nor are they emanations from the deity or expressions of the deity. The “deity of streams” has now been promoted to a more diversified — and more powerful — “deity of waters”.

The benefit of this view is that now, whether you’re seeking to influence the stream close to your house or a lake one hundred leagues away, you need only appeal to the deity of waters to try to alter the behavior of the particular stream (or lake, or ocean) you’re concerned with.

Thus, you have progressed to …

Religion

Religion as a word comes into English from Old French word religion, meaning “a religious community”, borrowed from the Latin religionem, meaning “respect for what is sacred, reverence for the gods, sense of right, moral obligation, sanctity, obligation, the bond between man and the gods”. The word is as complex as the concept it names.

“Religion” may be defined as…

… a cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that relates humanity to supernatural, transcendental, or spiritual elements. However, there is no scholarly consensus over what precisely constitutes a religion.

Or, as Frank Herbert put it: “Religion begins where men seek to influence a god.”9

In addition, there are two types: personal religion and organized (or institutionalized) religion.

Personal Religion

Personal religion grows out of individual experience of spirituality, and thus is unique to each individual. In personal religion, you develop regularized rites/rituals/ceremonies by which you, personally and individually, express your spiritual experience(s), and which you use to interact with the deity in charge of whatever aspect of the natural world you wish to influence (e. g. the deity of waters). These practices are based solely on your own experiences of the natural world, your own personal history of what seems to work most often in relation to which deity, and (perhaps most importantly) what seems never to work at all.

Organized (Collective/Community) Religion

Organized religion probably originally began as something more like collective spirituality. Groups of people, seeking to find commonality and community in their various personal religious experiences, began to gather together to attempt to invoke shared spiritual experiences. This seems like a natural development; human beings are gregarious – we prefer being part of a group to being a lone individual.10

Over time, certain of these shared practices seemed to be more efficacious or satisfying than others, and came to be first preferred and later required. Also, the sense of community identity could become entwined with the particularities of the group’s collective spiritual beliefs and practices.

Thence, organized or institutionalized religion often becomes the rites/rituals/ceremonies which you use to interact with the deities, but which have been invented by someone else (often far in your past) and are taught to you as practices which you perform without question and which you are not empowered to modify or ignore at will. If it becomes rigid and intolerant it is said to have crystalized.

A physical example may prove valuable, here. In fundamental science studies, children are often given the experience of dissolving sugar or salt in warm water and then suspending a string in the water, to be left undisturbed for a period of time. Over the course of the succeeding days and weeks, crystals of sugar (or salt) begin to form, clinging to the string.

While the sugar or salt is dissolved in the water, it is said to be “in solution”. The individual molecules of sugar or salt are “free agents”, able to be wherever within the jar that physical forces dictate them to be; but once they begin to attach to the string and to each other, they crystallize, and their liberty of motion is stripped from them. Once a part of the growing crystal, the molecule may now exist in only one place in relation to other molecules, frozen and entrapped.

Crystallized organized religions tend to be inflexibly exclusive and to differentiate with prejudice between pantheons and practices, and are thus easily transformed into social control mechanisms, at which point they cease to have any real connection to spiritual needs and awareness, at all.

Your deity of waters is now distinct from my deity of waters, and (usually) mine is viewed by me as being more powerful (or more primal, or more proper — “Only we understand and wordship the True Deity Of Waters; your deity of waters is an imposter, a charlatan, or an enemy of the True Deity of Waters.”).

The rites/rituals/ceremonies of others you regard as flawed (at the very least) if they differ from yours. Sometimes, others’ “wrong beliefs and practices” just make them ignorant or misguided in your eyes; sometimes, it makes you judge others to be actively dangerous to yourself and your beliefs.

Mergers of Tradition

Sometimes, societies merge (by conquest or some other mechanism). When this happens, one mythology or religion might become dominant and completely supplant the other (usually that of the stronger or more populous group). Sometimes, though, if the two groups are closely enough related or closely enough equal in power and influence, the two belief systems will merge into a new set of practices that can be staggeringly complicated to the point of incomprehensibility.

We see this in ancient Greek religion, wherein Helios is a deity of the Sun, but so is Apollo. Apollo (from the more influential of the melded religions), became the de facto deity of the Sun, while Helios got relegated to the status of a minor deity — one who simply drives the chariot in which Apollo traverses the sky. Nevertheless, ancient myths can still be found in which Helios is referred to and interacted with as if he were the sole solar deity.

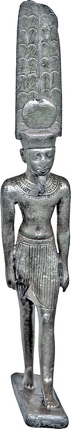

Something similar happened in Egypt, where the Sun is associated with three deities: Amun (Amon, Amen), Ra (Re), and Aten. Worship of Amun and Ra see figure 4.1 dates to the Old Kingdom (2575 – 2150 BCE), with Amun prominent at Thebes, and Ra dominant at Heliopolis (an Egyptian city with a Greek name: “The City of Helios”).

The third deity, Aten, rose to prominence during the Middle Kingdom (1975 – 1640 BCE), again at Thebes, and became exclusive through the pharaonic decree of Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) during the only monotheistic (see below) period of ancient Egyptian history, the Amarna Period (1353 – 1336 BCE).

Aten’s worship was centered at the desert city of Akhetaten (modern-day Tel el-Amarna), built specially for the purpose by Akhenaten (and destroyed after his death). After Akhenaten’s reign, polytheism was restored (most probably by Tutankhamun, who changed his name from Tutankhaten in order to show his change of allegiance).

The earlier deities, Amun and Ra, later became conflated as Amun-Ra (Amon-Re) and celebrated at the temples of Karnak and Luxor.

Who’s In Charge, Here?

From this brief discussion, you’ll likely have noticed a singular problem. If there’s more than one deity who is said to have influence over a given natural phenomenon (e. g. Helios and Apollo both as solar deities), and neither has taken a prominent position in your religion, then to which should you appeal in order to get your needs met and your wishes fulfilled? If you sacrifice to the “wrong” one, the other might decide to punish you, which is quite the opposite of what you’re hoping to make happen!

In Persia, at some time after 1500 BCE, a semi-legendary figure named Zoroaster (Zarathustra) also promoted a single-god solution as Akhenaten had (though almost certainly motivated by different intentions). Zoroaster’s historicity is not firmly established, so it is hard to unequivocally state whether he or Akhenaten was first, but they both promoted …

Monotheism

The word “monotheism” comes from the Greek words μόνος, “monos”, meaning “single” and θεός, “theós”, meaning “god”. This is deceptively simplistic, as no ostensible “monotheistic” religion existing in the world today actually is one (more on this below). The idea of monotheism is that …

… there is only one deity who created the world, is all-powerful, and intervenes in the workings of the world.

… and it comes in two flavors: inclusive monotheism and exclusive monotheism.

Inclusive Monotheism

Inclusive monotheism declares that “the deity is the highest being within the class to which it belongs.”

That is to say that there is a class (which we might call “divinity”), and the deity is the exemplar of that class. Other beings might exist which are divine, but only the Deity is deific. These other beings may do the bidding of the deity, but they are not deities, themselves. They also may be coincident with the deity, or may have been created by it (or some of both).

By contrast …

Exclusive Monotheism

… asserts that

… the uniqueness of the deity is in terms of an absolute difference in kind from all other reality. The deity does not belong to a class called “divinity” nor is it the supreme instantiation of a transcendent, generic divinity, nor is it a personification or embodiment of the natural world.

For example, Joseph Campbell pointed out:

The biblical condemnation of nature that [the Abrahamic religions] inherited…. [says that] God is not in nature; God is separate from nature and nature is not God…. [There is a general] derogation of ‘the nature religions’. This distinction between God and the world is not to be found in [other religions].

What is shared by both of inclusive and exclusive monotheism is that the deity is singular in its power and position, and that it is responsible for all of creation and all subsequent states of the universe in perpetuity.

An Abusive Parent?

This means, then, that all of the good things that exist or happen in the world are caused by the deity, as well as all of the bad things that exist or happen in the world. Thus, if the weather is affable and you have a bonanza harvest, then the deity has blessed you. However, if lightning strikes your house and it burns to the ground, the deity caused that to happen, too. You have been cursed or punished, though you may have no idea what you’ve done to deserve it.

Your priest or shaman can hazard a guess and give you some sort of penance to perform, but only time will tell whether you have mollified the god and avoided yet more divine retribution. If something (like a plague or a famine) affects your whole society, you may become convinced that the whole community has gone astray and is being punished. This has much the same psychological effect as a capricious human parent who periodically strikes you to the ground “just because.” It’s emotionally traumatic!

Enter Dualism

So, rather quickly, the darker side of the deity is spun off into a separate entity, a being who is disorderly, destructive, and demonic. Now you are free to believe that the deity still loves and cares for you, but sometimes the “evil one” gets in a lucky blow and does you harm. The religion is said to have altered into a dualistic cosmology. The word dualism comes from the Latin duālis meaning “containing two” or “relating to a pair”.

This happened to Zoroastrianism, in which the original monotheistic deity, Ahura Mazda, became the “good” deity, responsible for all the positive aspects and events of the universe, while Ahriman came to be assigned all the negative aspects and events. In this balanced dualism, these two deities are seen as absolutely equal to one another in power, locked in an eternal conflict for dominance, which neither of them can ever win.

In Zoroastrian thought, humankind is immersed in this cosmic conflict between good and evil, both within the individual and within culture/society. The internal struggle is manifest in that every one of us has the capacity for self-centered or malicious behavior that benefits us while doing harm to others. If (when) we succumb to those villainous impulses and act on them, we manifest the cosmic struggle externally, as when one group engages in harmful attitudes (and actions) toward another. The conflict within becomes the war without (this is why Campbell says that mythology can be viewed as a sort of ancient form of psychology).

Despite their claims (and seminal desires) to be monotheistic, the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), have implemented their own versions of this dualistic cosmology by positing a dark, negative, malignant being who acts in opposition to the will of Yahweh/Jehovah/Allah. However, this being — Satan (the adversary) in Judaism; Lucifer in Christianity; Shaitan/Iblis in Islam — is a rebellious creation of the deity, and thus these systems are examples of unbalanced dualism.

There are other, subtler “relatives” of monotheism, such as …

Henotheism

This is the practice of believing in and worshipping only your own deity, while not denying or decrying the existence of other deities: “I only worship my god, but your god is real, too.” The word comes from the Greek roots ἑνός “heno”, “one, of one thing” and θεός, “theós”. Thus, it means “of one god” and henotheism is generally regarded as being fundamentally monotheistic in character, which is to say that you, personally, or your culture, collectively, worship only one deity.

As mentioned above, your neighbor may have a “deity of waters”, which you recognize and respect, but you exclusively worship your single deity while not deprecating your neighbor’s worship beliefs and practices. In fact, in ancient times, it was quite common for nomadic peoples to make a sacrifice to the local god(s) when entering someone else’s territory.

Akhenaten’s monotheism was exclusive within Egypt and the areas it controlled, but was indifferent to the religions of its neighbors, so it could be said to have been locally exclusive, but broadly henotheistic.

Zoroastrian religion was (is) certainly henotheistic. When the Persian king, Cyrus the Great, conquered Babylon in 539 BCE, he allowed the Jews to return home. In addition, he gathered up all of the relics of the destroyed Temple of Solomon that he could find and sent them back to Jerusalem, as well, along with sums of money intended to help the Jews in rebuilding the Temple. Because of this, Cyrus is the only non-Hebrew king spoken well-of in the Old Testament. (The Greeks viewed him rather differently).

Also, in contrast to Akhenaten’s Atenism, which was abandoned after the pharaoh’s death, Zoroastrianism is very much a living religion. Freddie Mercury (Farrokh Bulsara) of the rock band Queen, was born a Zoroastrian.

Monolatry

This is a similar practice to henotheism, but monolatry is a belief in the existence of many deities while consistently worshipping only one of them: “There are dozens or hundreds of gods, but I only worship [insert name here]”. This word, too, is Greek, from μόνος “monos”, meaning “single”, and λατρεία “latreia”, meaning “worship”. So, this word describes a practice more so than a belief system.

In monolatry, your religious system may have any number of deities, but you worship only one of them, exclusively. You neither deny nor decry the existence and worship of other deities in your own pantheon, and (as in henotheism) you also take no exception to others’ religious practices outside your own traditions. For instance, different city-states in ancient Greece had patron deities: Athena in Athens, Ares in Sparta, Zeus in Olympia, Poseidon in Corinth. Yet, while Athena was specifically revered in Athens still Ares, Zeus, and Poseidon were fully recognized as legitimate members of the broader Greek pantheon.

Kathenotheism

This term was coined by the German philologist Max Müller (1823 – 1900 CE) from the Greek words Καθ’χένα “kath’hena”, “one by one” and θεός “theós”, meaning “god”. It literally translates as “one god at a time”.

In this religious system, you have several recognized and active deities, but you worship only one at a time. For instance, you might have a deity for each of the seasons, such that when it is summertime, you worship the Deity of Summer, but when autumn arrives, you shift your worship to the Deity of Autumn, and so on, rotating through the seasons and the deities until you come back to the beginning and start again. Some modern Wiccan practices have elements of this type of worship, focusing alternately on the Maiden, Mother, and Crone. We also see a dim reflection of kathenotheism in the Greek worship of Demeter and Persephone.

Kathenotheism can be inclusive or exclusive; you may worship your particular set of deities and be content to let others worship after their own fashion, or you may insist that your pantheon is the only true one, denigrating the deities of others.

Other Relatives of Dualistic Cosmology

There are several beliefs and/or practices which have been identified and which share some characteristics with the dualistic cosmologies described above, while standing apart from them in other ways.

Duotheism

This word is a combination of the Latin word duo “two” and the Greek word θεός “theós”. This is the belief in the existence of exactly two deities, no more and no less. They may be of the same gender (as in Zoroastrianism), or of complementary genders, such as the belief in a god and a goddess of roughly equal power, as is the case in some modern Pagan practices. Duotheism can also be inclusive (recognizing and respecting others’ deities while not worshiping them) or exclusive (asserting that your deities are the only legitimate ones, not only for yourself but for everyone else, and that others’ deities are false, at best, or demonic, at worst.)

Bitheism

This word comes from the Latin root bi–, meaning “twice” and the Greek word θεός “theós”, and it describes a belief system which recognizes two deities which are not in conflict or opposition, but also not necessarily in alliance, either. Rather, the two are in exclusive forms or states (such as male and female), and their forms serve to identify their individual spheres of interest and influence. There were elements of this in the ancient Egyptian worship of Isis and Osiris.

Bitheism implies harmony (or at least amity) between the two deities; they may work in concert, or simply avoid interfering with one another. Again, this practice can be inclusive or exclusive.

Ditheism

This word is a combination of the Greek roots word δύο “two” (later becoming δī “di–”) and the Greek word θεός “theós”. This is a cosmology which implies rivalry and opposition between two deities or divinities, such as between gods of good and evil, or of light and dark, or even perhaps gods of summer and winter. For example, a ditheistic system could be one in which one deity is a creator, and the other a destroyer. Once again, both inclusive and exclusive practices are possible. Zoroastrianism is ditheistic in at least some of its aspects.

Finally, there is the concept of …

Transcendence

This is the idea that a deity’s nature and power is wholly independent of the material universe and beyond all physical laws (see “Deism” and “Agnosticism”, below). As described above, some versions of the Abrahamic religions hold that Yahweh/Jehovah/Allah is transcendent (though active in the material world). In fundamental Hindu thought, Mahavishnu (the “great god”) is transcendent, containing the physical universe but greater than it, possessing but not expressing all duality within itself. Mahavishnu, however, has no direct influence on the corporeal world; it must incarnate14 as a physical being in order to affect material reality.

Uncertainty and Antipathy

There are two philosophical expressions that describe levels of uncertainty about deities and divinity: deism and agnosticism.

Deism

Deism (ultimately from the Latin deus, meaning “god” in the generic sense) is a belief system which gained widespread popularity in the European Enlightenment (1715 – 1789 CE) after the publication of treatises like Lord Herbert of Cherbury’s book of 1624, De Veritate.

In deism, you state that a deity does, in fact, exist as an uncaused prima causa or causa causans (“first cause”; “a cause which causes”), and that it is ultimately responsible for the creation of the universe. Nevertheless, you believe that such a deity does not interfere directly with the created world, nor does it practice divine revelation, whereby it might make its plans for the universe known through miracles or direct communication with humankind. It is, thus, transcendent, but also uninvolved.

Thus, for you, while a deity exists, and while its design and plan for the universe are discoverable and knowable through the exercise of human intellect, its motivations and goals are unknown and unknowable by any human means, whatsoever. Ultimately, its nature is so foreign to human understanding that it is pointless and counterproductive to even attempt to understand it.

This is the “watchmaker analogy”, which states that there is an obvious, discernable design in the universe and its functioning; and, if there is a design, there must be a designer; but, the designer is forever beyond human ken. We may come to understand its works, but never its motivations nor its nature.

Superficially, Deism can be seen as an effort to bridge pre-Scientific Revolution mythos with the logos of the European Enlightenment in an attempt to make it possible to be a natural philosopher (scientist) and still believe in God. Many of the Founders and Framers of the fledgling United States were practitioners of Deism.

Agnosticism

The word “agnostic” comes directly from the Greek; the prefix a-, meaning “not, without” and the Greet word γνῶσις “gnosis” meaning “knowledge”; thus, “without knowledge”. Agnosticism is a similar philosophical position to Deism, which differs from it in one important regard: the agnostic refuses to take any stance regarding the existence of a deity.

In general, the argument runs something like: “The existence of a deity, of divinity, or of the supernatural in general, is unknown and/or unknowable, and human reason is incapable of providing sufficient rational grounds to justify either the belief that a deity exists or the belief that a deity does not exist.”

Thus, while Deism believes in an extant-but-unknowable deity, agnosticism declares that certainty (either way) on this subject is impossible and unworthy of pursuit. In Zen parlance, to even ask the question “Is there a god?” is to “make a meaningless noise.”

Voices for The Opposition

There are two philosophies which are opposed (and sometimes actively hostile) to spiritual/religious belief and practice: atheism and antitheism. The second is much more aggressively antipathic than is the first.

Atheism

As with “agnostic”, the word “atheism” comes directly from the Greek; again the prefix a-, meaning “not, without” is used, but it is now attached to the root θεός (theós, “god”), and thus means “without (a) god”.

Atheism, simply put, is

… the absence of belief in the existence of deities; in other words, atheism is the rejection of belief that any deities exist, and specifically the position that there are no deities, nor is there any possibility or necessity for deities to exist.

There is much philosophical debate as to whether such a philosophy is actually practical; a famous dictum declares that “there are no atheists in foxholes,” which is to say that, under the right stressful circumstances, even the staunchest denier of divinity will fall back on appeals to a higher-order consciousness for solace and consolation (or even salvation).

Nevertheless, many people are self-identified atheists, citing any number of personal experiences and/or observations to support their argument that the universe is blithely indifferent to humans (“The universe is not hostile, nor yet is it friendly. It is simply indifferent”) and that only human beings — through the exercise of their intellect and ambition — are capable of achieving a greater control over the universe and ending human suffering thereby.

Many (if not all) of those who define themselves as “humanist” also identify as atheist.

Antitheism

… is the stringent (and sometimes violent) criticism of theism (in any-and-all of the forms discussed above). The word combines the Greek root θεός (theós, “god”), as above, with the prefix anti- (Greek, ultimately from Sanskrit ánti, meaning “opposite or against”), and so, straightforwardly, means “against (the idea of or belief in) a god or gods”. Often outspoken in their views, antitheists believe that spirituality, theism, and religion are actively harmful to society and to individuals, and that even if theistic beliefs were true, they would be undesirable.

Antitheism asserts that theistic — and especially religious — beliefs and practices should be discarded in favor of humanism, rationalism, science, and/or other alternatives, and some antitheists even assert that religion and/or theism should not only be discouraged, but actively oppressed in the process of ultimately eradicating them from culture and society. The antitheist sees all spiritual expression as mere superstition, to be supplanted by logic and reason.

Humanism

Predicated on the notion that “… of all things the measure is Man”,19 humanism, broadly, is the philosophical stance that reason, scientific inquiry, and human fulfillment are the paramount activities and goals of life and that anything which detracts or distracts from these goals is wasteful (at best) or harmful (at worst).

Humanism in its original formulation began in Ancient Greece, and saw a revival in the European Renaissance as a rebellion against the prevalence of religious belief and the perceived primitive superstition of the preceding “Dark Ages.”

While some “humanists” are staunchly anti-spiritual, anti-theism is generally not considered a de rigueur requirement for humanist thought and practice.

Non-Committal Views

In contrast to atheism and antitheism, there are two views that “take the higher ground” on the arguments about the questions of the existence of divinity and/or deities: autotheism and ietsism.

Autotheism

Autotheism comes from the Byzantine Greek αὐτόθεος “this (or the) God” from ancient Greek αὐτο– (auto, “this”) + θεός (theós “god”), and is the viewpoint that — whether or not divinity is also external — it is inherently within oneself and that one has the ability to achieve spiritual transcendence, either through self-discovery, or by following the examples set and implications extant in statements by (or attributed to) ethical, philosophical, and/or religious leaders.

For some it also includes the belief that one’s self is a deity. Some Hindus use the term, aham Brahmāsmi which means, “I am Brahman”, referring to the impersonal, supreme being, the primal source and ultimate transcendental goal of all beings, with which the individual, when enlightened, knows itself to be identical (sometimes, but not always, identified with Mahavishnu).

“All beings have Buddha nature because all beings have within themselves what we call the essence of the Buddha, the … potential for enlightenment.”

Ietsism

Ietsism [itsˈɪsm] is an unspecific belief in an undetermined and indeterminate, yet necessarily transcendent reality. This view is held by people who suspect or actively believe that there must be something undefined, which exists beyond anything which can be known or can be proven, nevertheless, they do not necessarily accept or subscribe to any established belief systems, dogmas, or views of the nature of a deity as offered by any particular religions.

An ietsist would agree with Joseph Campbell’s words that there exists “… that which transcends all thinking, all thought…,” and we can only express “…metaphors referring to what is absolutely transcendent.”

The name comes from the Dutch word ietsisme [itsˈɪsmə], meaning “somethingism”.