3. Context and Culture

Context is always culturally bound; implicit meanings are different between societies depending on how each chooses to interpret the world (their worldview). The most important word in that sentence is “chooses”; in our study of mythology and its socio-cultural antecedents and legacy, it should never be far from our consciousness that cultural norms and societal expectations are choices that result from reactions to the environment in which a people find themselves.

One of the fascinating aspects of studying mytho-history is exploring the questions of why a particular people chose the paths they did, rather than others that may have been available to them at the time. The choices they made affected the direction their culture and society progressed. And the process by which a culture/society perpetuates its worldview in each succeeding generation is called acculturation.1 So, what are some of the mechanisms by which individuals and societies construct their acculturated reality?

Paths to Context

Context Through Experience: Recall and Recognition

We see what we see according to what we “know”; what “makes the most sense”; what we are expecting to see. This might be summarized by saying that “experience creates expectation”. An excellent way to approach this is through optical illusions.

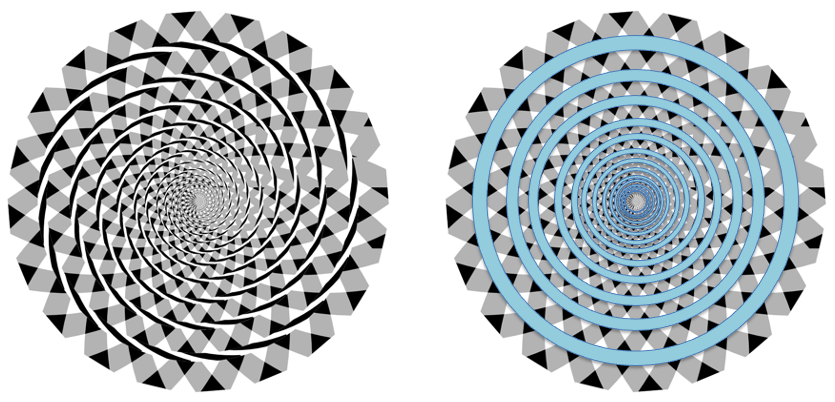

In figure 3.1 below, you see a spiral pattern on the left, because your experience tells. you that an object shaded in such a pattern must be a spiral; in fact, the illustration is composed of concentric circles. And the critical point to be noted here is that even though you know it is a series of concentric circles, you still see a spiral. Your expectations, rooted in your experiences, enforces a conclusion on your consciousness which is in contradiction to what your intellect knows to be true.

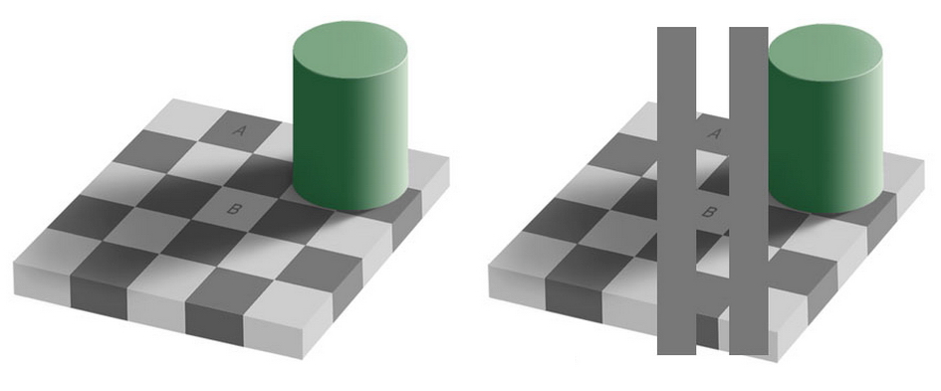

Similarly in the illustration below figure 3.2, your experiential expectation tells you that the square labeled B must be lighter than the square labeled A, because B is in a shadow, and objects visible in a shadow must be of a lighter shade. However, the illustration on the right shows that both squares are, in fact, the same shade of grey. Again, however, even though you know that A and B are the same shade, when you look at the left-hand illustration, you continue to see B as lighter than A.

The point, here, is that you can only judge a circumstance or situation based on the data you have at-hand, and if that data is confusing or conflicting, your experience is ambiguous, and thus your conclusion may be mistaken. However, you are not “wrong” to come to a particular conclusion based on the information you are aware of, as long as you bear in mind that your data is likely incomplete and your conclusion is, perforce, provisional.

The houses and trees in the picture at left figure 3.3 are “obviously” tilted, because you see a street, a postal service vehicle, and a sidewalk which are all “obviously” level. All of your past experience tells you that the ground is level, so anything at an angle to it is leaning. This “knowledge” makes the bulk of the picture make sense, so even though you probably have no personal experience of houses being built at a tilt, you see these as being so, because all of the rest of the picture makes sense according to what you already “know”.

It is only when more data becomes available, by rotating the picture figure 3.4 (at right), that you are able to determine that your original conclusion was mistaken. The street is inclined on a hillside, and the vehicle is traveling toward the crest of the hill. Even so, knowing what you now know, when you look back at the first picture above, you still conclude that the houses are built at a tilt, even though you know they are not.

Your experience creates your expectations, and this is a very pervasive phenomenon in your interactions with the world. As a further example of how powerful expectation can be, consider the image below.

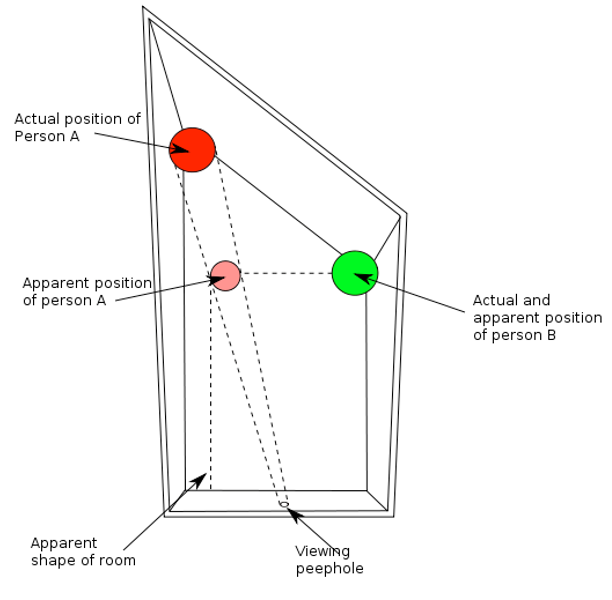

The man on the right figure 3.5 is clearly a giant, about nine feet tall. The woman on the left is about average height, the corner between the walls and the ceiling above her seems to be at an appropriate height; the niches between them are of appropriate dimensions, and are located on the wall at the expected height. The woman on the left is looking up at the giant man on the right. Both are pointing directly at one another.

Everything else about the picture makes sense collectively, so the man on the right must be a giant.

However….

The room is not square; the woman on the left is farther away than she appears to be, and her gaze is not actually directed at the woman on the right.

Consider this question: which is the more likely explanation for the top image — that the room isn’t square, or that the woman on the right is a giant?

Well, how many 9-foot-tall women have you met in your life? Not very many, right? (Probably none). So, that is not a likely reality to assume.

Yet, your brain really wants that room to be square! So, it assumes a square room, and all of the other apparently obvious information in your field of vision that supports the conclusion that the room is square supports that assumption, so you conclude that the room is square and that one of the women is a giant, even though that is the least likely explanation.

Culturally Bound Expectations

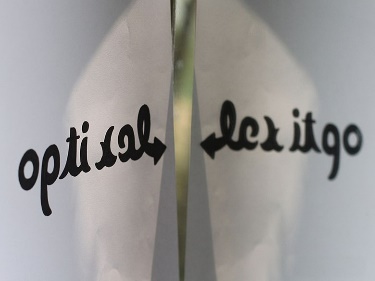

In the image at right figure 3.7, you likely see the word “optical” on the left, and the advice “let it go” in the reflection. It is the same set of squiggles, but because you are acculturated to be on the lookout for letters of the Latin alphabet in their various forms, you interpret the squiggles as Latin letters — but which letters depends on the order in which you “read” the squiggles.

English, and most other languages which are written using a Latinate alphabet, are written from left-to-right, and top-to-bottom. So, you view the image, itself, from left-to-right, and the same with the squiggles. This illusion is culturally bound, because if someone were from a culture in which writing is not done in a Latinate alphabet (say an Asian language like Mandarin Chinese, which is written top-down and right-to-left), and they have no experience of Latinate letters and writing, then this illusion might not work for them at all. Such a person would not have been acculturated to expect Latinate letters, and so would not automatically see them.

Further, in the image at left are the Chinese ideograms for the concept of “wisdom”; if a viewer is not acculturated to read Chinese ideograms, then they may recognize the characters as being Chinese “writing”, but have no knowledge of their meaning. If rotating the image 90° produced an entirely different configuration referring to an entirely different concept, such a change would be obvious and entertaining to a reader of Mandarin Chinese, but remain utterly meaningless to anyone not acculturated to read the characters.

This is the immense power — and danger — of experiential expectations: they can lead you into coming to a snap conclusion which is mistaken, at best, and, at worst, harmful … to yourself and others.

This does not mean that you are “wrong” to make decisions about a situation based upon the information you have at-hand; that is all anyone can ever do — to start with. The admonition here is to always try to remember that there is very likely more to know about a situation than you immediately comprehend; that any immediate conclusions you may come to are necessarily based on incomplete data; that your conclusions will almost certainly require reassessment and reconfiguration after the acquisition of more information; and, that “changing your mind” once you know more is proper and admirable, rather than something to be seen as a failing or a weakness. This brings us to a similar concept.

Context Through Granularity: The Devil’s In The Details

Much of what we perceive is dependent upon the details we can distinguish. Chefs and food connoisseurs often speak of the subtle hints of various ingredients or spices which make up a dish; vintners and wine enthusiasts speak of “bouquet” and “finish”; composers and musicians listen for “timbre” and “pitch”, etc.

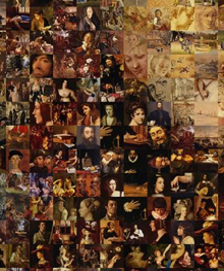

At right figure 3.10, we see a reproduction of da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, composed of smaller images of the paintings of a variety of other artists from different places and times. When we look closely at one corner of the image figure 3.9, we can distinguish the smaller images that comprise it, but looking at the image as a whole, we see only the ”big picture”, the composite image.

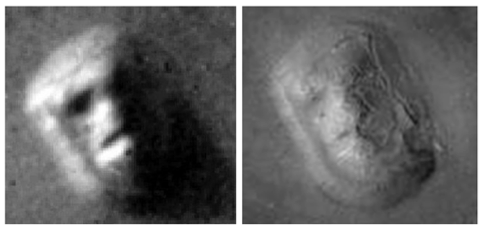

A similar situation occurred when the image on the left, was taken by the Viking 1 orbiter over Mars in 1976 of a geographic formation in the Cydonia region of the surface of Mars. A later photograph taken by the Mars Global Surveyor in 2001 contains much more detail and reveals the “face” to be an illusion. This is an example of a psychological effect known as pareidolia, the perceptive tendency to impose a meaningful interpretation on an ambiguous stimulus, which can lead to mistaken interpretations.

Context Through Modality: Preferences and Biases

Sometimes (often?) what we perceive is influenced (determined?) by what we want to perceive (or what we choose to believe). Fiction (and history) is full of examples of parents refusing to recognize evil in their children and of spouses deluding themselves about the fidelity of their partners. Other times, people come to a snap decision, and feel compelled to “stick with it”, even in the face of overwhelming contradictory evidence or out-and-out proof of their original mistake. Simply put, people don’t like to believe that they’re gullible, naïve, easily fooled, and will often “put a different spin on” a situation in order to alleviate this discomfort, or to cover for a lack of knowledge when they think admitting ignorance would reflect poorly on them.

Take, for example, The Arnolfini Portrait, painted by Jan Van Eyck in 1434 CE, and currently on display in the National Gallery in London, England. This is a painting replete with symbolism, but for our discussion let’s focus on the little dog in the middle foreground. Why is the dog in the painting?

To modern eyes and sensibilities, we might be inclined to conclude that the couple was fond of their pet and wanted it included in their family portrait. This is not a “wrong” explanation, and in the absence of any other information, it is an adequate explanation.

However, this is a portrait commemorating a marriage ceremony, and knowing this additional information permits a more in-depth interpretation of the meaning of the dog’s presence. A very popular saying is that “Dog is man’s best friend”; a declaration predicated on the belief that dogs are generally reliable, faithful, dependable companions. This leads to a new interpretation when combined with the dog’s location within the painting: in the foreground, directly beneath the couple’s touching hands. Now, combining these facts, we can expand our interpretation of the dog’s presence to be symbolic of the faith and trust the man is placing in his new wife as a result of their new legal status.

If we further research the painting and include the facts that the painting was produced in the Netherlands at a time in history when the people of that part of Europe were exploring and colonizing Africa, Asia, and the Western Hemisphere; that they were becoming fabulously wealthy as a result of exploiting newly discovered resources and newly conquered peoples; and, that this produced in them an interest in business matters that we might today define as “obsessive” — the symbolism takes on even deeper meaning: not only is the man trusting his new wife with his heart, he is entrusting her with his worldly wealth, as well.

Audiences viewing the painting in the fifteenth century when it was originally produced would likely have immediately discerned the meaning of the dog’s presence; more modern audiences, with differing interests and focus, require more information to encompass the painter’s original purpose.

This can result in misleading interpretations, either accidentally, or through the manipulation of an audience’s unconscious biases by an agent making use of an image or symbol. Take, for example, the picture below figure 3.14:

Upon first exposure to this image, it would be completely natural and understandable for a modern audience to conclude that this was a mid-twentieth century photograph of schoolchildren in Nazi Germany saluting a swastika flag or perhaps paying respect to a large poster of Adolf Hitler. However, the picture has been cropped; here is the original figure 3.15:

The Bellamy Salute was a required element of the United States Pledge of Allegiance in the period between 1890 and 1942; its use was discontinued precisely because of its similarity to the salute which had been adopted by the fascist parties of Italy and Germany earlier in the century2.

An unscrupulous person could use the first image to support a report about indoctrinated German schoolchildren under Nazi rule. Or, someone could use the second image to “prove” that there was a strong and widespread fascist sympathy in the United States prior to World War II3.

The point, here, is that anyone encountering either image and not exercising critical thinking to question whether or not what they were seeing was legitimately what they were being told it was, would be participating in potentially malicious manipulation of their consciousness.

This is a crucial point to understand in the study of mythology: unless you are hearing or reading a mythical story communicated directly from a member of the culture which originated it, or unless the myth you are encountering has been reproduced in the native language in which it was originally expressed and you are fluent in that language and its subtleties and intricacies, then the myth you’re dealing with is going to have undergone some level of translation and interpretation.

This is not to say that all reproductions of myths by members of non-native cultures are maliciously misrepresented (though some certainly have been in the past); it is simply a reminder that any given retelling is subject to the unconscious biases of the translator/interpreter sharing the story, especially in regard to the words they choose to use in interpreting the words from the original language. As the saying goes, “Something is always lost in translation.”

So, when you are exploring a retelling of a myth and you encounter a term that is unfamiliar to you, or one which seems to be an odd use of a word you believe you’re familiar with, don’t just shrug it off and keep reading. Stop and research the term; the word may have other meanings of which you are unaware, and the translator/interpreter may have intended it to be understood according to one of the less well-known meanings4.

It can also be valuable, whenever possible, to consult other retellings of the same story, to see how different translators/interpreters have chosen to depict the characters, circumstances, and message of the story. If most retellings are similar, but one is markedly different in specific ways, this can help you to uncover possible malicious misrepresentation of the myth or its originating culture.