12. The Heroic Journey

Early Explorations

One of the earliest academic attempts to address the nature and particulars of the Heroic Archetype was The Myth Of The Birth Of The Hero (1909), by Otto Rank. Based on a psychological analysis (using Sigmund Freud’s methodology) of the story of Œdipus, Rank divided the Heroic Arc into twelve constituent parts.

Otto Rank’s Heroic Path1

- Child of distinguished parents

- Father is a king

- Difficulty in conception

- Prophecy warning against birth

- Hero surrendered to the water in a box

- Saved by animals or lowly people

- Suckled by female animal or humble woman

- Hero grows up

- Hero finds distinguished parents

- Hero takes revenge on the father

- Acknowledged by people

- Achieves rank and honors

While this list does a good job of enumerating the character, circumstances, and events of the Œdipus’ life, it has several drawbacks. First, it is specific to one myth only, that of Œdipus. Second, it is, therefore, entirely focused only on the male heroic figure, and is anchored upon the characters relations and interactions with his parents. Finally, Rank’s list is limited to the first half of the character’s life, and does not concern itself with the legacy effects of their journey.

Thus, while Rank’s work is a notable first effort at a logos analysis of heroism, it doesn’t serve our needs well in our study of mythology because it is a purely psychological interpretation; it is more descripting than prescriptive; and it is exclusive to Eurocentric male characters.

In 1936 Fitzroy Richard Somerset (Lord Raglan) published The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama. His analysis resulted in a list of 22 items (which Raglan, himself, admitted was entirely arbitrary), also focused entirely on Indo-European cultural patterns surrounding exclusively male heroic characters.

Lord Raglan’s Heroic Path2

- Mother is a royal virgin

- Father is a king

- Father often a near relative to mother

- Unusual conception

- Hero reputed to be son of god

- Attempt to kill hero as an infant, often by father or maternal grandfather

- Hero spirited away as a child

- Reared by foster parents in a far country

- No details of childhood

- Returns or goes to future kingdom

- Is victor over king, giant, dragon or wild beast

- Marries a princess (often daughter of predecessor)

- Becomes king

- For a time he reigns uneventfully

- He prescribes laws

- Later loses favor with gods or his subjects

- Driven from throne and city

- Meets with mysterious death

- Often at the top of a hill

- His children, if any, do not succeed him

- His body is not buried

- Has one or more holy sepulchers or tombs

In a valiant attempt to impose logos upon mythos, Raglan’s system is applied by checking off on the list any-and-all characteristics which apply to one’s chosen character, awarding them 1 point for each item achieved. The higher the ultimate total, the more heroic the character is determined to be. Raglan, himself, scored several mythological, legendary, and historical figures and assigned them scores:

Lord Raglan’s Scoring of 21 Mythical, Legendary, and Historical Figures

|

|

Name |

Raglan Score |

| 1. |

Oedipus |

21 |

| 2. |

Moses |

20 |

| 3. |

Theseus |

20 |

| 4. |

Dionysos |

19 |

| 5. |

King Arthur |

19 |

| 6. |

Perseus |

18 |

| 7. |

Romulus |

18 |

| 8. |

Watu Gunung |

18 |

| 9. |

Heracles |

17 |

| 10. |

Llew Llawgyffes |

17 |

| 11. |

Bellerophon |

16 |

| 12. |

Jason |

15 |

| 13. |

Zeus |

15 |

| 14. |

Nyikang |

14 |

| 15. |

Pelops |

13 |

| 16. |

Robin Hood |

13 |

| 17. |

Joseph |

12 |

| 18. |

Apollo |

11 |

| 19. |

Sigurd |

11 |

| 20. |

Elijah |

9 |

| 21. |

Alexander the Great |

7 |

Several problems attend Lord Raglan’s scoring system, not the least of which being that Raglan saw all heroic stories as literal history, rather than symbolic or metaphorical, which leads to possible confusion of historical figures with mythological characters.

Thomas J. Sienkewicz, Minnie Billings Capron Professor Emeritus of Classics at Monmouth College in Illinois, applied Raglan’s scoring system3 to several fictional characters and historical figures, and found that the historical characters often scored higher than the fictional characters:

Thomas J. Sienkewicz’ Application of Raglan’s Scoring System to Six Mythical and Historic Figures

|

|

Name |

Raglan Score |

| 1. |

Mithridates VI4 |

22 |

| 2. |

Jesus of Nazareth |

18 |

| 3. |

Muhammed |

17 |

| 4. |

Buddha |

15 |

| 5. |

Czar Nicholas II |

14 |

| 6. |

Harry Potter |

8 |

Again, while Raglan’s system is interesting, and represents a valid attempt at codifying heroism, it falls short of meeting our present needs in studying the Heroic Archetype.

Joseph Campbell

Campbell broadly defined the Heroic Act as “…departure, fulfillment, return”.5 In this volume, we’ll refer to these as the phases of a Heroic Arc.

Broadly, in the first phase (Departure), the Heroic character is made aware of the Challenge they will be facing, commits to the adventure, and enters embarks upon the journey. In the second phase (Fulfilment), the Heroic character encounters difficulties which both test their dedication to the adventure and grow their heroic capacity to deal with the Challenge; acquires allies, identifies antagonists, and either obtains the Solution or the information that will produce the Solution to the Challenge. Finally, in the third phase (Return), the Heroic character brings or communicates to the “Ordinary World” the Solution (or its formulation) to the Challenge.

Departure: Preparation

Fulfilment: Progression

Return: Presentation

Joseph Campbell said that “… all the myths have to deal with … transformation of consciousness”.6 He was referring to both the consciousness of the individual and of the collective. This is true especially of the Heroic archetype — the Heroic undergoes a personal transformation of consciousness which enables or empowers them to contribute to the potential transformation of a collective consciousness in which they participate.

Fundamentally, the three phases are expressed in three main aspects:

- Willingness to Sacrifice

- Transformation of Personal Consciousness

- Potential to Change the Ordinary World

An important point must be made, here: the Willingness to Sacrifice need not always extend to the actual death of the Heroic — willingness to suffer sacrifice of any variety, be it self-image, physical health, social standing, etc., is equally as valid as risking physical death, depending upon the nature of the Challenge and the concomitant adventure it engenders.

By employing broad terminology in the naming of the aspects, it encourages inclusive thinking when contemplating whether-or-not a character’s story arc is heroic; one is not distracted away from recognizing a character as heroic purely on the basis of some particular attribute, such as race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.

Each of these three phases have certain elements which are associated primarily (but not exclusively) with them. Joseph Campbell, in The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949), enumerated the aspects (or steps, as he called them) as seventeen in total.

Campbell’s Heroic Journey

|

Phase |

Aspects |

|

Departure |

The Call to Adventure |

|

Refusal of the Call |

|

|

Supernatural Aid |

|

|

Crossing the Threshold |

|

|

Belly of the Whale |

|

|

Initiation |

The Road of Trials |

|

Meeting With The Goddess |

|

|

Woman as Temptress |

|

|

Atonement With the Father |

|

|

Apotheosis |

|

|

The Ultimate Boon |

|

|

Return |

Refusal of the Return |

|

The Magic Flight |

|

|

Rescue From Without |

|

|

The Crossing of the Return Threshold |

|

|

Master of Two Worlds |

|

|

Freedom to Live |

However, despite his largely universalist view of mythology, some of Campbell’s original steps are still predicated on androcentric and Classicist ideas of the heroic. For instance, “The Meeting with The Goddess”, “Woman as the Temptress”, and “Master of Two Worlds”.8 The first two of these assume a masculine Heroic relating to the feminine energy, antagonistically in the case of the Temptress. In the third, the primary problem is in the word “master,” which both carries both gender-biased and socially inequitable connotations.

Christopher Vogler: Heroism As A 12-Step Program

The most straightforward presentation of the Heroic archetype for an effective study of mythology is encoded in the twelve steps of Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey (as adapted from Campbell’s original 17-step cycle):

Christopher Vogler’s Heroic Journey10

|

Phase |

Aspects |

|

Departure |

The Ordinary World |

|

The Call to Adventure |

|

|

Refusal of the Call |

|

|

Meeting With The Mentor |

|

|

Crossing the Threshold |

|

|

Fulfilment |

Test, Allies, and Enemies |

|

The Innermost Cave |

|

|

Ordeal |

|

|

Reward |

|

|

Return |

The Road Back |

|

Resurrection/Purification |

|

|

Return With the Elixir |

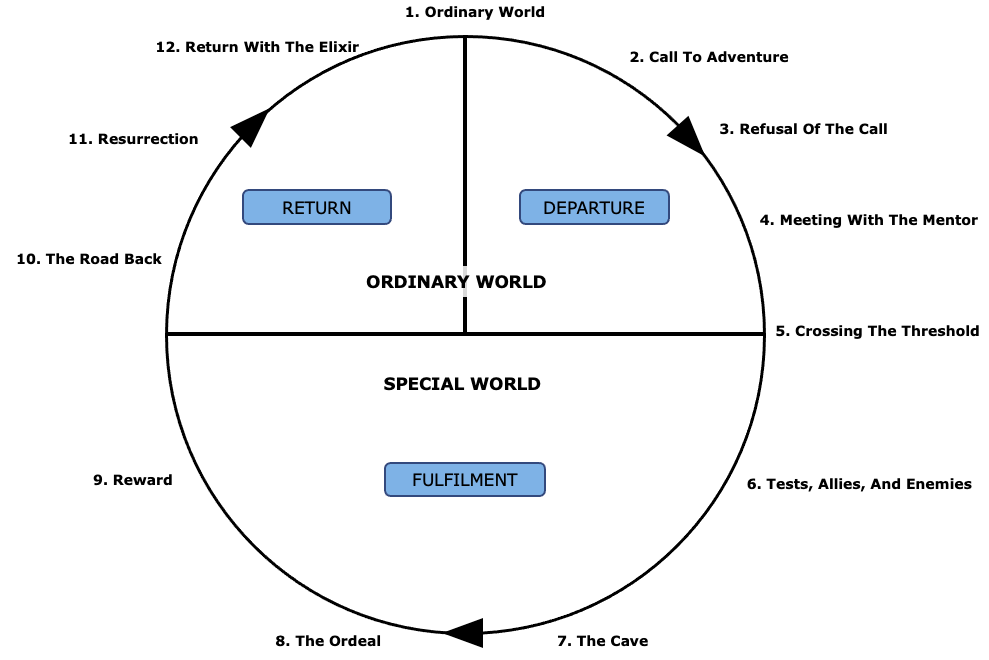

Vogler both broadened and condensed Campbell’s Heroic Arc. The twelve more generalized stages see figure 12.1, which served to open the system to mythologies both old and new, remove limitations to its universal applicability. This arrangement also provides a workable framework for the consciously equitable construction of new Heroic paradigms which are both contemporarily relevant and yet timeless.

The simplification to twelve “steps” fitted into the three broad categories makes remembering the steps and their primary association to the Heroic Journey easier and more straightforward. It is Vogler’s system which forms the foundation (with some minor modification of terminology) of our exploration of the Heroic Archetype.

Some of the benefits of Vogler’s system are: firstly, that it is fundamentally inclusive; Heroic status is not gender-centric, race-centric, or even species-centric. Any character which shows a Willingness to Sacrifice and experiences a Transformation of Personal Consciousness, which leads ultimately to realization of a Potential to Change The Ordinary World can be said to have undergone a heroic adventure.

Secondly, Vogler’s system allows for the construction of a story line which is not slavishly formulaic. While certain aspects are more strongly identified with a given phase, they are not necessarily exclusively associated with any particular phase. “Meeting A Mentor”, for instance, is enumerated in the Departure phase, but meeting any mentor can actually happen at any point in the journey — the Fulfilment or even the Return phase. While “Tests, Allies, and Enemies” are most commonly found in the Fulfilment stage, any of these may also appear (and often do) in the Departure phase.

Thirdly, Vogler’s system not only lends itself admirably to analyzing existing Classical and traditional heroic mythologies, but it also provides a workable framework for generating storylines that are conscious of current affairs and are, therefore, readily approachable and engaging to contemporary audiences, yet still couched in symbols and metaphors which are universal and eternal.

Vogler, thus, reinforces Campbell’s emphasis that the Heroic archetype was originally intended as an aid, a guide, and a comfort for everyday human life: a guidebook for “how to live a human lifetime under any circumstances.” However, inherent in the traditional Heroic journey is the limiting assumption that the goal of the Heroic’s actions is, in itself, worthy and worthwhile and beneficial to “the greater good.” History, if not the Heroic’s own society, must see their deeds as laudable, selfless, martyrly, etc. A more modern understanding of the Heroic is less constricted.

Graphical Representation of Vogler’s

Twelve Steps of the Heroic Journey

The Departure Phase

The Ordinary World

The Ordinary World is, the character’s origin, the environment with which they are familiar and comfortable. As Campbell put it, it is “… the realm of light, which [the Heroic] controls and knows about.”12 Starting the account of the heroic journey in the Ordinary World serves to create a contrast with the Special World in which the bulk of the adventure (and transformation) takes place.

For some stories, this is a simple enough task; if you’re writing a detective story, and you start out with her office phone ringing and she answers to find it is someone wanting to hire her for a job, you don’t have to explain to your reader what a phone, an office, or a detective is, nor why someone would be seeking to hire her. You can assume the audience is already familiar with these things, and can get right to describing the nature of the Challenge.

Now, if you’re writing about Hobbits in a Shire in Middle Earth…. what are these things? You have to take the time to familiarize your audience with these aspects of your heroic character’s Ordinary World before you can even begin introducing the Challenge. If you do this introductory job well (and not in a tedious manner), then your audience will be able to spot when the heroic character enters the Special World of their adventure, because it will have obvious differences and departures from the character’s Ordinary World.

The Call to Adventure

This is when the character is presented with the first indications that a Challenge is looming; it establishes what is at stake. The Call to Adventure may take many forms, and may either be a singular, striking event (a meteor hits the city and the Heroic has to locate survivors and get them to safety), or it may build up slowly over time (little oddities here-and-there catch the Heroic’s attention, slowly adding up to an undeniable awareness that something has gone wrong and needs to be addressed. This second option is often employed by creators who need to familiarize their audience with an alien Ordinary World; by having the Heroic note departures from the normalcies of their life, those normalcies are surreptitiously described.

The Call to Adventure may also be presented to the Heroic by another character, often an as-yet unidentified Mentor (see below). Usually the Challenge takes the form of an onus on the Heroic to right a wrong or seek justice, restore a disrupted status quo, rescue an abductee, etc.

Refusal of the Call

Here, the character balks at the threshold of adventure, refuses to take part, or expresses reluctance to become involved, a natural reaction — especially for the Accidental or Forced Heroic — as they are facing the greatest of human fears: that of the unknown. This unknown is multi-dimensional. “What is the nature of the Challenge? What has brought it about? What is there to be done about it? Am I up to the task of meeting the Challenge? How will I go about it? What if I fail?”

Often at this juncture, the Heroic is provided with encouragement or added motivation (usually — but not always and not necessarily — by a mentor) to engage with and undertake the adventure, such as revealing to them how horrific the world will become, or how much damage will be done if they don’t choose to act.

Meeting with the Mentor/Sage/Wise One

This is one of the most common themes in mythology and is rich in symbolic value, capturing the bond between a knowledgeable guide and a neophyte adventurer. The wisdom of experience is offered to the novice in order to help them prepare for the rigors of addressing the Challenge. Sometimes, magical artifacts or special technology is passed along, as well as secret knowledge that may give the Heroic a small advantage at the beginning of the task.

There are two very important points to be aware of here:

- Though this is listed as the fourth step in the Heroic Journey, the Heroic can (and often does) meet various mentors at various junctures during the journey. It is unusual for a single mentor to have all of the knowledge and experience to which the Heroic will require access in order to “level up” to the task of identifying, finding, and acquiring the Solution to the Challenge.

- No mentor can accompany the Heroic throughout the entire adventure. As Campbell says to Moyers: “If you have someone who can help you, that’s fine…. But, ultimately, the last trick has to be done by you.”13 This is a crucial element of the relatability of the Heroic (see below for details); the audience must believe that there is a real chance that the Heroic will fail (possibly fatally), so that their ultimate survival and success carry the psycho-emotional release and elation that makes a heroic story so satisfying.

Active and Passive Forces

It is important to take a quick aside here to talk about active and passive allies and antagonists.

An antagonist is any person, place, thing, or circumstance which impedes the Heroic in the furtherance of their quest. For instance, encountering a great chasm in the earth with no bridge in sight represents a physical passive antagonist: a natural obstacle14 the Heroic must figure out how to overcome before they can continue on their way.

An ally is any person, place, thing, or circumstance which aids the Heroic in the furtherance of their quest. To continue with the above example, if the Heroic travels along the edge of the chasm and encounters a bridge spanning it, the bridge acts as a passive ally,15 providing a way to cross the chasm so that the journey may proceed apace.

The Mentor (assuming there is one overarching character who repeatedly carries this archetype) is an active ally (the primary one); their purpose is to help ensure that the Heroic learns the knowledge and gains the skills necessary to complete their adventure and achieve their goal.

The Villain (if the Challenge is personified) is the primary active antagonist, embodying the two-fold purpose of 1) achieving their own nefarious goals; and 2) preventing the Heroic from quashing their plans.16 Any accomplices the Villain may employ are also active antagonists, as long as their actions are directed specifically toward impeding the Heroic’s progress and preventing their success.

Another very important point that must be stressed here is that any person, place, thing, or circumstance which provides the Heroic with knowledge or experience that strengthens their resolve, improves their odds of success, grants them special powers, etc. is a mentor.

Thus, the Villain is, in this sense, a mentor to the Heroic, because the Villain presents an example of everything the Heroic doesn’t want to be or to do in the pursuit of their goal. The Heroic learns from the example of the Villain, “I know I don’t want to be (or do) that!”

This reminds us that knowledge, power, capability, etc., have no inherent moral/ethical nature — it is always the use to which they are put which is subject to moral/ethical analysis and judgement.

Crossing the First Threshold

This is the point at which the Heroic overcomes (or at least sets aside) their fear of the unknowns ahead of them, decides to (at least attempt to) confront the problem, and takes the step of entering the Special World. In this moment, the Accidental or Forced Heroic becomes just Intentional enough to agree to face the consequences of taking action.17

This step shares with the Call to Adventure the characteristic that it can happen in a single act, or be drawn out over time — although there always is a single step that accomplishes the actual migration into the Special World.

In the latter case, there usually exists a “buffer zone” between the Ordinary World and the Special World, and the Heroic has some small knowledge of the buffer zone, such that it is not completely nor well-known to them, but it is not utterly and entirely foreign, either. Events within this buffer zone often help strengthen the Heroic’s resolve, clarify the nature of the Challenge, drive home the urgency of their quest, etc., so that they are as fully committed as possible when finally confronted with the actual portal into the Special World.

The Fulfillment Phase

Tests, Allies, and Enemies

This “step” comprises all of the problems and obstacles, as well as the answers and aids, the Heroic encounters within the Special World that continue to expand their knowledge, capabilities, and especially confidence in themselves that are necessary to achieve their goal.

However while most tests occur in his phase, tests may (and usually do) occur in the Departure and Return phases, as well — indeed, overcoming the Refusal of the Call (if there is one) is the first major test the Heroic faces, and it occurs before the Special World is entered.

Also, further allies and agents of the enemy are often encountered in this phase, bringing with them vital experiences and wisdom which will contribute to the Heroic’s incremental and ultimate successes.

(Approach to) the Inmost Cave

The Inmost Cave is the most dangerous location in the Special World, in that it is the place where the Heroic is in the gravest danger of failing and becoming incapable of continuing, let alone completing, their quest.

Take heed that the Inmost Cave need not be an actual cave; nor even a physical location, at all! A setback which causes the Heroic to doubt their commitment, question their fitness to their chosen role, contemplate giving up, may present as an internal psycho-emotional struggle, rather than an all-out hack-and-slash battle with the most overwhelming monster they’ve yet encountered.

The Ordeal

In any case, the struggle which takes place within the Inmost Cave is the Ordeal; it is not the last test which the Heroic will face before their triumphal return to the Ordinary World, but it is the test which determines once-and-for-all whether they will finish the journey in success, or die in the attempt.

It is worth noting, here, that the Heroic’s Willingness to Sacrifice is ultimately what is being tested here, and it may run the gamut from simply acknowledging their fear to accepting their death. Success in the Ordeal is, first-and-foremost, final acceptance of whatever consequences result from confronting the Challenge and acting to acquire the Solution. The Heroic embraces whatever their fate is going to be and publicly declares, “Whatever the cost to myself of overcoming the Challenge, I will gladly pay it.”

The Reward

The Reward has several faces; the most important of them is simply the survival of the Heroic — be it physical, emotional, spiritual…. They have passed the test, proven (to themselves and everyone else) that they are fit to the task and stronger than their adversary. Sometimes, though not always, the actual Solution is part of the Reward: the magical sword is obtained; the crucial medicine is acquired; the correct code is deciphered…. The power exerted by the Challenge (and/or the Villain) has been taken by the Heroic and may now be applied to eradicating the Challenge and the threat it poses.

This phase sometimes also involves a reconciliation of some sort, with a parent, lover, friend, or even with oneself. An adjunct to this is that the Heroic often becomes “more attractive” as a result of overcoming the Ordeal. This may mean an actual physical transformation into a more appealing form, but more often than not it is more a case of increased charisma in the eyes of their aides and followers — who become fully convinced that they “backed the right horse”, and rededicate themselves to seeing the quest through to its completion.

The Return Phase

The Road Back

The Heroic may have acquired the magical item, technology, knowledge, etc., necessary to apply the Solution to the Challenge, but they still have to transport whatever it is back to the Ordinary World where the Challenge is actively having its effects. Possessing the medicine to cure a malady is pointless unless the medicine is applied to the affliction.

There is often a “chase scene” in this phase, when the forces of the Villain pursue the Heroic in an attempt to reclaim the Reward. Sometimes (unless a sequel is already planned) the Villain, themselves, is actually defeated and destroyed at this time. The Heroic is not “home free” just yet.

Resurrection (Purification)

In many Classical myths, because the Heroic has been in the Realm of the Dead or similar environment, there is a necessity for them to be “purified” before re-entering the Ordinary World, so that they don’t bring any harmful or malicious influences back with them.

This isn’t always a literal aspect of modern popular culture stories, though there is an analogous aspect — public acknowledgement of their accomplishment. The Heroic is “purified” and welcomed back into the Ordinary World by the recognition of others of what they have endured and accomplished; a collective statement that “we know what you suffered, and we approve of your actions.”

It is crucial to note, however, that this is in no way a requirement of the Heroic Act. Even if no one ever knows what the Heroic has done; even if those who will benefit from the Solution do not acknowledge its worth; even if those who are saved reject and vilify the Heroic, their act was still heroic. It comprised a Willingness to Sacrifice, a Transformation of their Personal Consciousness, and resulted in a Potential to Change the Ordinary World — and these three are the only requirements of a Heroic Act. Nothing else, whatsoever, has any bearing on whether an act was heroic, as long as these three things are true.

Return With the Elixir

An elixir is, of course, a potion or concoction of some kind (usually magical) that holds the power to effect change. In this case, the term simply refers to the Solution, itself, which is brought back to the Ordinary World by the Heroic.

Again, there is an important note to be taken here: 1) the Solution need not be applied by the Heroic, themselves, in order for their act to have been Heroic; and 2) the Solution need not be applied at all, in order for their act to have been Heroic. The Ordinary World, indeed, may reject or ignore the Solution if it so chooses; the Heroic’s actions are still Heroic, even if, in the end, others choose not to eliminate the Challenge and its effects.

This is a singular problem with modern conceptions of the Heroic: the focus is placed upon the end result, rather than the process. Heroism exists in the action, not the outcome. This is very clear when it is recalled that the archetypes are a vocabulary of actions, not an enumeration of accomplishments.