11. The Pedagogical Function And The Heroic

Vocabulary Notes

- I prefer the term “Heroic character” (or, simply “Heroic”) to “hero”; the latter tends to be androcentric in English, and as such tends to perpetuate limiting, gender-binary thinking, as well as promoting exclusion rather than inclusion as a central motif of the Heroic Archetype. While it is true that in many Classical and traditional mythologies, heroism was often the exclusive domain of males (and then only of males of a certain type), a universalist understanding of mythology and of the archetypes recognizes the Heroic as fundamentally inclusive and accessible.

- For purposes of diversity and inclusion, I use the generic pronoun “they” when speaking of the Heroic in generalities and hypotheticals; however, in reference to existing Classical and traditional myths, the gendered pronouns will be used to refer to Heroic characters commonly accepted to be male or female, or when quoting an original source when the generic masculine pronoun is employed.

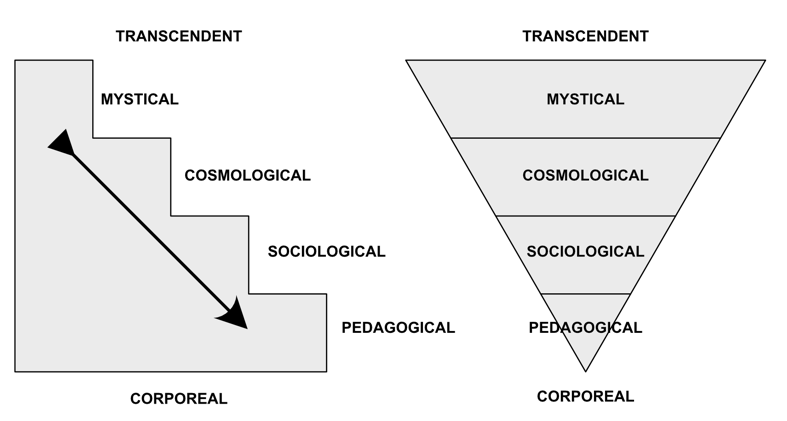

The Pedagogical Function, though it is the fourth and “lowest” function on the Mythic Structure Diagram see figure 11.1, is in many ways the most important, as it is about the “… experience of being alive”1, within the context of the other three functions. It is about the question, “How do I do this thing called Life, in a way that fulfills me and expresses my individuality and uniqueness (Pedagogical Function); in a way that is minimally disruptive to the culture and society of which I am part (Sociological Function); in a way that is minimally destructive to the natural environment of which I and my culture/society are a part (Cosmological Function); and in a way which keeps me ‘… in accord with the universal being’2 (Mystical Function)?” What a typically complex-simple question!

If we simplify the Mythic Structure Diagram as a perspectival image of a set of stairs viewed from above, we see that the exploration of mythology is like walking down those stairs (figure 11.1), with each step bringing us closer to our destination, yet each step also having a part of its meaning carried forward from the step above it.

The content becomes ever more specific, even as the context becomes ever broader. Think of looking closely at a painting of a landscape: the whole picture may be of a stand of trees, but as you get closer and closer, you are able to make out particular trees, then separate branches of that tree, and finally individual leaves on that branch of that tree, but you are still aware that the leaf you’re inspecting is on a branch attached to a tree in a painting of a lot of trees.

The Nature of The Heroic Archetype

As explained above, all archetypes act as “… vocabulary in the form, not of words, but of acts and adventures…” Thus, the fundamental impulse of an archetype is to act, to behave in certain ways. This is especially true of the Heroic; its raison d’être is to act in response to some event, situation, circumstance (collectively, a Challenge), and for the benefit of others who may be unable or unwilling to act on their own behalf. The Heroic seeks to find (though not always to directly implement) a Solution.

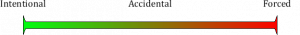

This brings us to Campbell’s three Heroic types: Intentional, Accidental (Serendipitous), and Reluctant (Forced).4 These are by no means exhaustive categories (see below), nor will all “heroic” characters necessarily fall definitively or exclusively into one of these three.5 However, these categories do serve as a workable wrapper within which to begin to explore the Heroic Archetype.

The Intentional Heroic

In some ways, this is the least relatable (more on this later) of the three types. The Intentional Heroic seeks adventure; one might say that they “go looking for trouble”. The Intentional Heroic is already quite self-assured in their abilities to confront and vanquish Challenges; they simply seek an opportunity to display their prowess (usually the more ostentatious the better). Joseph Campbell mentions “… a typical early-culture hero who goes around slaying monsters”6 (the Monster-Slayer Heroic); this is a subtype of the Intentional Heroic — they see it as their job to make the world “safe” for humanity, and they go in search of ways to do just that (more on this below).

The Accidental (Serendipitous) Heroic

This type of Heroic character is carried by circumstance into a situation of needing to act in response to a Challenge. Something unexpected happens which requires a response, and the Heroic character finds that they are the only one who can (or is willing to) act to address the situation.7 In essence, the Accidental Heroic becomes involved in an adventure by happenstance. The classic example of this heroic type is Alice In Wonderland; she literally falls into her adventure by plummeting down the rabbit hole. Yes, she followed the White Rabbit in order to satisfy her curiosity, but she had no intention of going anywhere beyond her familiar and comfortable garden in doing so.

The central motif of this aspect of the Heroic Archetype is codified by Robert Frost’s famous observation that “… the best way out is always through.”8 In other words, we may not be happy about the situation, but we must stoically accept that it is what it is and work toward a solution.

In Alice’s case, she cannot return via the route by which she arrived. Her only options are to sit at the bottom of the hole and starve, or to act on her own behalf to find another way to get home. She may not immediately know what is the right thing to do, but she knows for certain that inaction is the wrong thing.

President Theodore Roosevelt is supposed to have said: “In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing,”9 often rendered down to the more prosaic “Do something, even if it’s wrong.”

The Reluctant (Forced) Heroic

This type of Heroic is compelled by another’s actions into responding to a Challenge. The difference between the Accidental Heroic and the Reluctant Heroic is subtle but crucial. They are similar in that in neither case is the character actively seeking an adventure. They differ in the nature or source of the Challenge faced, how the Heroic becomes aware of it, and how they react to it (at least initially). For the Accidental Heroic, often the Challenge is simply the result of happenstance, not malice. As J. H. Holmes observed, “The universe is not hostile, nor yet is it friendly — it is simply indifferent.”10

Or, as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes in Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, “A meteorite on a collision course with New York City [is only] obeying all the laws of the universe, but it [is] still a damn nuisance.”11 The meteorite isn’t acting out of malice; it didn’t consciously choose its path, but it still represents a problem to be dealt with.

On the other hand, a foreign army using trebuchets to lob boulders at your castle walls also presents you with a Challenge, but it’s one they’re forcing you into choosing whether or not to deal with. You may not have sought conflict, but there it is. A less severe example is when someone else makes a decision which impacts you, and you have to decide how to respond — receiving an unexpected break-up text, for instance. You didn’t choose to upend your life, but it has been upended, and you have to decide how you’re going to adjust. It is helpful to see these three options as points on a continuum see figure 11.2:

… arranged in terms of both the attitude of the character toward heroism and of their willingness to engage with the Challenge. The Intentional can think of nothing they’d rather do;, the Forced would rather do just about anything else, and the Accidental is somewhere between the two extremes (and may, in fact, vacillate around the median frequently as the adventure proceeds).

However, the Accidental and Forced types must become Intentional (to a greater-or-lesser degree) at some point in the process of the adventure. This doesn’t mean that the character must adopt a gung-ho enthusiasm for their situation, but they must become at least resigned to the fact that the best way out is always through. This often results in “The Heroic In Spite of Themself” trope wherein the character struggles (or even petulantly complains), but takes the necessary actions, nevertheless.

The Heroic archetype is the manifestation of the Pedagogical Function, which “teaches us how to live a human lifetime under any circumstances,” as Campbell so poetically puts it. It has manifested in many guises in human cultures around the world and across time, but the heroic character is always a product of the society which produces it, and thus reflects the stresses its progenitor society is experiencing at the time of the archetype’s emergence (and which it is manifested to resolve).

Part of the purpose of the Pedagogical Function and of the Heroic archetype is to help individuals address those circumstances wherein the needs of self-expression conflict with the duties of social obligation. For example, an action which might have been questionable behavior for your grandparents may be a survival necessity for you. Contrariwise, some things your grandparents may have taken for granted as their just due as human beings may today land you in court. As Campbell says, “The virtues of the past are the vices of today, and many of what were thought to be the vices of the past are the necessities of today.”

Finally, there is Campbell’s lesson that there are two types of Heroic deed:

One is the physical deed; the hero who has performed a war act or a physical act of heroism — saving a life, that’s a hero act. Giving himself, sacrificing himself to another. And the other kind is the spiritual hero, who has learned or found a mode of experiencing the supernormal range of human spiritual life, and then come back and communicated it.14 [emphasis added]

The physical deed is the fundamental character of the action-hero movie in the modern medium, and it may apply to any of the three Heroic types, even the Forced, because such a Heroic character is required to perform a physical feat, even if it is the last thing they’d have chosen to be doing.

The spiritual deed is less common in the modern, post-Enlightenment idiom, though such stories are still told from time-to-time. The contemporary analog might be called the intellectual deed, in which learning information or adapting one’s thinking to view the situation in a new way is what leads to the discovery and application of the Solution.

The Distributed Heroic

Just as the Trickster archetype can be taken on by more than one character in a story (even at the same time), so it can be with the Heroic. There are three chief expressions of this: 1) the Aggregate Heroic; 2) the Sequential Heroic; and 3) the Partite Heroic.

The Aggregate Heroic

This is a very common trope in the modern medium; a group of characters of Heroic nature who possess various Heroic qualities and (often widely) varying personalities, working together to address a particularly powerful or widespread Challenge. Two stand-out examples, of course, are Marvel’s Avengers and DC’s Justice League. Each character is Heroic in their own fashion, all are working toward the same goal, and all are displaying Heroic qualities simultaneously, but their individual efforts are concentrated on separate parts of the overall Challenge (with an occasional pairing or grouping for variety).

This expression of the Heroic is a very open-faced expression of the realization that a single person often does not have the totality of the power, talents, and/or capabilities to address all the aspects of a Challenge single-handedly (in contrast to several Classical Heroics — such as Herakles — who acted as individual, free-agent executors of the Solution).15

The Sequential Heroic

In this expression, the Heroic archetype is taken on by various separate characters at different times in the adventure; again, all are Heroic after their own fashion, and usually each has a special talent or ability which is addressed to a specific aspect of the Challenge, but each operates individually, one-at-a-time. The Heroic archetype is passed from one character to another like the baton in a relay race (sometimes cycling through the group several times), as each component of the Challenge is met and dispensed with in progression toward the ultimate victory.

This is often seen in suites of novels which are all set in the same milieu, but in which each title is dedicated to a particular character (often, but not always, addressing an entirely independent Challenge than that faced by other Heroic characters in other books, and sometimes in entirely different historical periods of the setting).

The Partite Heroic

This trope is about as common as the Aggregate Heroic, and has a somewhat longer history. In this configuration, the archetype of the Heroic is shared among several characters (usually either two or three, but rarely more), simultaneously, and each character represents a specific aspect of Heroism. However, in this case, it is more as if the characters represent personality traits of a single individual, such that the Heroic archetype is wholly present only because all of its component parts are present.

An excellent example of this is found in Star Trek: The Original Series,16 in which McCoy, Spock, and Kirk represent, respectively, the affective/subjective aspect of the personality (McCoy); the practical/objective aspect (Spock); and the motivational/applicational aspect (Kirk).17 This implementation can be found in the earliest trilogy of Star Wars18 movies, in which Luke can be seen as the Kirk-like character; Han as the Spock-like character; and Leia as the McCoy-like character — though there is hardly a point-for-point correspondence.

Another way this can be implemented is by assigning the spiritual/intellectual aspect of the deed to one character, and the practical/physical aspect of the deed to another character. A very good example of this can be seen in Independence Day19 (1996), in which David Levinson (played by Jeff Goldblum) comprehends the intellectual aspect of the Challenge (that the signal shared between the alien craft is, in fact, a countdown, coordinating their simultaneous destruction of several major population centers around the world), and Captain Steven Hiller (played by Will Smith) understands and is conversant with the physical aspect of the Challenge (actively countering the aggressive and destructive actions of the aliens).

While Hiller is engaged in piecemeal dispatching aliens who are in the act of killing humans,20 Levinson reasons out the aliens’ organizational structure, finds its weakness, and formulates a counterattack which will eradicate the threat at its source Ultimately, for the solution to be implemented, both must come together and act in concert: Hiller flies the salvaged alien craft to their Mothership, where Levinson infects their computer system with a virus which causes it to catastrophically malfunction, and they leave behind a nuclear weapon which destroys the craft, thus “cutting the head off of the snake”.