10. The Sociological Function And The Trickster

The Sociological Function, which Campbell decried as having, “… taken over in our world … ethical laws, the laws of life in the society … what kind of clothes to wear, how to behave to each other … in terms of the values of this particular society”, is a narrower focus than the Cosmological Function. Whereas the latter seeks to describe and explain the nature and working of the objective physical universe, the former concentrates on the institutions and practices that are specific to a particular culture’s social functioning and interactions. The Cosmological Function often describes the origins and creation of humankind, the Sociological Function, in part, is the vehicle for “… validating or maintaining a certain society; ethical laws, the laws of life in the society … the values of [a] particular society.”2

Thomas Hobbes, in Leviathan, believed that humans originally existed in a State of Nature3 in which the natural condition is for each person to do whatever seems best to ensure their own survival and thriving. They spent their time competing ceaselessly with one another over limited resources and life was, “… solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”4

Hobbes goes on to explain that eventually people realized that oftentimes more can be achieved through cooperation than competition, but that for cooperation to be engendered and maintained, certain limitations must be levied against the liberty of the individual by the collective.

Some behaviors, mandatory in the State of Nature, must be curtailed or proscribed in the social environment in order to ensure the smooth functioning of collective efforts. Social stratification, hierarchy, and structures of legislation and systems of justice all resulted from the advent of collective life and livelihood.

Thus, there are numerous behaviors available to the individual because of their inalienable right to personal liberty which must be voluntarily surrendered for the benefit of the group. The other side of this coin, of course, is that the group also reserves the right to require certain behaviors from the individual which are not necessarily naturally voluntary.

In other words, the collective decrees some behaviors as approved, and others as prohibited. Engagement in approved behaviors elicits rewards; transgression of prohibitions induces punishments. In this way, the Sociological Function is associated with the Trickster archetype, which may be justifiably termed “the most human” of all the archetypes.

William Hynes, et. al., in Mythical Trickster Figures: Contours, Contexts, and Criticisms, identifies and enumerates “… a number of shared characteristics [which] appear to cluster together in a pattern that can serve as an index to the presence of the trickster. At least six similarities … can be identified,”5 but these should not be viewed as in any way exhaustive or proscriptive.

The six characteristic qualities or behaviors6 are:

- Ambiguous and Anomalous: the nature of the Trickster, its motivations and goals are never clear or concise; as soon as one believes they have “nailed the Trickster down”, it will alter its behavior to escape definition.

- Deceiver and Trick-player: the most commonly recognized trickster trait; whatever the Trickster appears to be, it is always something more; any act it performs will always have unexpected (though not necessarily always malicious) results.

- Shape-Shifter: whatever guise the Trickster appears in, there is always more than meets the eye; and the Trickster is supremely talented at either actually changing its physical form, or at least disguising itself (often playing its opponent’s own naïveté against them).

- Situation-Invertor: similar to Shape-Shifter, any situation in which the Trickster is involved is certain to have more aspects and complexity than a cursory inspection reveals.

- Messenger and Imitator of the Gods: Tricksters are often (unwisely?) employed by divine authority to announce or disseminate their decrees and pronouncements, and in this way the Trickster often seems to (or actively does) take on the mantle of authority, itself.

- Sacred and Lewd Bricoleur: a tinker or jack-of-all-trades, the Trickster is adept at using whatever objects or circumstances are at hand to fashion the means and accomplishment of its trickery.

Some of these characteristics have areas of overlap, in that a given behavior may be identified as falling into more than one category. For instance, in the Nez Percé story “How Beaver Stole Fire From The Pines,”7 Beaver hides under a bank in order to snatch up an ember from the fire.

Beaver’s act of hiding can be seen as simple deception and trick-playing (he is not making his presence known); a form of shape-shifting (he is disguising his own nature to appear as simply part of the natural surroundings); situation-inversion (the Pines believe their meeting place to be secure, when it has, in fact, already been infiltrated); acting as bricoleur (Beaver didn’t construct the bank under which he hides — it was already there and he simply made use of it); and, finally messenger of the gods, in the sense of bringing a boon from the divine realm to the mundane realm (Beaver’s intent is to bring fire to his people, à la Prometheus).

It is more of a stretch, but we could even invoke ambiguous and anomalous, in the sense that while thievery is generally frowned upon in civilized society, the intention and motivation of Beaver’s transgression is ultimately noble — he freely shares fire equally once he is in possession of it, whereas the Pines had been selfishly keeping the secret for themselves.

Lewis Hyde, in Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art, reveals other frequent aspects of the Trickster archetype. Firstly, he says that the Trickster archetype:

… begins with a being whose main concern is getting fed and it ends with the same being grown mentally swift, adept at creating and unmasking deceit, proficient at hiding his tracks and at seeing through the devices used by others to hide theirs.8

This hunger may be purely gastronomic, but it may stem from other id-centered sources as well, such as a desire for power, wealth, pleasure, security, etc. However, the object of such inducements, once acquired, is rarely enjoyed by the Trickster, for a variety of reasons. Either the food is inedible or unsatisfying, the object is less attractive once acquired, the authority is more onerous than glorifying, etc. This encodes the well-known adage to “be careful what you wish for, you may get it.”

This is effectively presented in the Aesop fable of the frogs and the stork, in which the frogs repeatedly entreat Zeus to send them a king to rule over them, but always find Zeus’ response inadequate or unsatisfying. Ultimately Zeus, simply to quiet their incessant pleading, finally sends a stork as King, which immediately sets to work devouring the frogs one-by-one.

Hyde also points out that the Trickster is often “hoist with his own petard,”9 getting “… snared in his own devices… [so] trickster is cunning about traps but not so cunning as to avoid them himself.”10

There is perhaps no better example of this in popular culture than Wile E. Coyote, the Warner Bros. cartoon character who is eternally being foiled by the very snares and devices he tries to employ to entrap the Road Runner. On more than one occasion, he is literally blown up by his own bomb.

The Trickster as Admonisher

On the wider sociological level, in true Trickster fashion, the Trickster serves simultaneously a dual purpose. The first of these, the admonisher, encompasses the cautionary tale, in which the Trickster serves to remind that punishments may befall an individual who refuses to adhere to divine and/or social mores and expectations. This relates to the “Messenger of The Gods” characteristic of the Trickster (see above), in which guise this archetype is often employed by the Moral Authoritarian Father god as a bringer of punishments to humans.

However, this aspect is also expressed in stories in which the Trickster is “back-tricked”: caught in its own trap, or has its own practices and methods used against it. Native American and African mythologies are rich with these kinds of Trickster tales. We observe Tricksters being punished by the negative consequences of their own actions (“…your sin will find you out”), by their leaders, or collectively by their communities, for engaging in misbehaviors such as refusing to share a bounty; for stealing rather than earning food or possessions; or, for causing disruption simply for the sake of watching the ensuing confusion.

This also points out the fact that selfishness and refusal to share is a major source of social disruption (especially within a small population) and may be viewed as a punishable offense by the group. A marvelous example of this is found in the White Mountain Apache story, “Coyote Steals Sun’s Tobacco,”12 in which Coyote, having stolen Sun’s tobacco, keeps it all for himself and is tricked by the community into giving it all away to them when they pretend to give him a house and a wife.13,14

The Trickster as Counselor

The second aspect of the Trickster we might call the counselor role; that of pointing out that it is not always the wisest choice to blindly obey the rules, especially if those rules have become outmoded and inflexible. The young child in “The Emperor’s New Clothes” is performing this Trickster function by refusing to subscribe to the dangerous “group-think” of the elders who know perfectly well that the Emperor is naked, but who are all afraid to speak the truth for fear of rejection by the group.

We also, however, see Tricksters in these myths “misbehaving” because limitations imposed on society are too rigid and thus detrimental to progress and growth (a prime example comes from the Greek tradition — Prometheus bringing fire to humanity in defiance of divine will). In this we find Campbell’s famous Trickster-Hero melding of archetypes (discussed later).

The Trickster, thus, manifests across a spectrum see figure 10.1 from the unconscious numbskull (think of the hapless Gilligan) who causes disruption unintentionally (sometimes as a result of poorly planned and badly executed attempts to do good); to a malicious spoiler16 (à la Rumpelstiltskin), who resonates to the baser drives of human nature and seeks self-advancement and personal pleasure at the expense of others. In this aspect, the Trickster also serves to remind a culture/society of what it values by profaning its sacred icons and institutions.17

The Trickster may be considered the most “human” of the primal archetypes, being able to associate with both mortals and with gods (Loki), perform feats of near superhuman daring and strength (Maui), and yet it is fallible and often incurs punishment, or at least reprimand. As the unconscious numbskull, the Trickster reminds us that fallibility is part of human nature; however, as the malicious spoiler, it teaches that our errancy is not a justification for willfully indulging our basest nature. The Trickster reminds us that we are fallible humans, which can make us evil if we consciously choose to follow our darker impulses.

Additionally, the Trickster is also the salve for human guilt over the need to kill to eat. Hunters who are weaker, slower, and/or less agile than their prey, in order to obtain meat, must be able to trick animals in order to kill them: wearing a buffalo hide to get close to the herd; setting snares; dangling worms on hooks, and so forth. Especially among earlier cultures and those which are still “connected” to the natural world, there is an overriding awareness that while killing to eat is an unavoidable necessity, it nevertheless requires a certain abuse of power over other living things.

As Campbell says, in part quoting Arthur Schopenhauer, “‘Life is something that should not have been. It is in its very essence and character, a terrible thing to consider, this business of living by killing and eating.’ I mean, it’s in sin in terms of all ethical judgments, all the time!”

Lastly, it is important to note that the vast majority of Tricksters in earlier mythic traditions are male in character. This is not because females are incapable of engaging in Trickster acts (indeed, in some cultures, females must become consummate Tricksters merely to survive), but in many (most?) cultures, females simply were not given the personal liberty to make a female Trickster believable to a given audience.

A signal departure from this is the Brule Sioux story of “Iktome Sleeps With His Wife By Mistake.”19 In this story, Iktome, his wife and the young girl with whom he attempts to have a dalliance all take on the Trickster archetype.20 Iktome seeks to fool the girl into having sex with him. The wife and the girl set out to fool Iktome and teach him a lesson about his self-centered motivations and behavior.

This Trickster-against-Trickster is a common trope seen, again, in the Coyote vs Roadrunner cartoons.

The counselor role of the Trickster can sometimes be the less appealing of the two, when the Trickster profanes the sacred as a means of revitalizing society’s focus on it. This often involves the most outrageous of acts – but that is the Trickster’s goal in performing them: to generate outrage (some might call it “righteous indignation”) by reminding people of what they claim to value but are actually taking for granted.

For example: in many communities around the United States, major supermarkets, “big box” stores, and malls (to say nothing of schools and government buildings) have huge American flags flying in their parking lots. Most of the time, these flags are simply part of the visual background of our lives; the only times we really pay them much attention is when we have to maneuver around the flagpole for a decent parking space.

Until someone takes one of them down and sets fire to it.

Then, we remember what it is we claim to value about that flag and we express outrage that someone would be so disrespectful to it … but then have to realize that we, ourselves, have been less than respectful to it by not paying attention to it under normal circumstances and forgetting to pay homage to the values we profess to treasure and which it represents.

You don’t have to like what the Trickster does, or what it is saying to you. You certainly don’t have to approve of its actions. In fact, most of the time the Trickster would prefer that you not approve. Its task is not to enhance equanimity, but to shatter complacency.

To this end, the Trickster “… pulverizes the univocal” by representing the “multivocality” of life:21 There is always more than one way to look at things, more than one valid viewpoint, more than one understanding of an experience.

This is also the task of the Trickster as the Situation Invertor. By turning a situation on its head, the Trickster reminds you not to fall into the trap of assuming that what you think is happening is all that is happening. When you are watching an even play out, whether it be on the television or on a social media feed, it is easy to forget that you are seeing only what that particular camera is pointing at in that particular moment. There is more going on that you’re getting access to.

In this role, the Trickster can overturn absolutely any person, place, belief, etc. The minute you think the Trickster has befriended you, it will betray you. The instant you think you’re safe, your location will become dangerous. The person who seems to have all the answers will be laid low. “No order is too rooted; no taboo too sacred; no god too high; no profanity too scatological.”22

And on that note, we are reminded that “Fecal matter, by its very nature, is anti-human and hence one of the most avoided objects and topics,23 so it forms one of the primary tools of the Trickster. What is meant, here, by “anti-human”? All living things, humans included, take in solid matter in the form of foodstuffs in order to survive. But think for a moment about what actually happens to the foods we consume.

The hamburger, for instance, is digested – literally broken down into constituent components – by the digestive fluids in the alimentary tract. Then, the body re-uses some of those constituent components to build new cells and tissues to replace those lost to age or damage. But not all of the constituent components of our food are useful for making new cells and tissues. Those components are gathered together as fecal matter and expelled from the body.

Therefore, fecal matter is composed of everything we take in as “food” that can’t be turned into replacement parts of us – it is, by definition, everything we are not. Add to this the fact that feces (and urine, for that matter) also carry away harmful microbes which our body has neutralized and needs to rid itself of, and it becomes abundantly obvious why our waste products are among our least favorite things.

And, yet, in typical Trickster fashion, it also forms a part of the definition of human. All humans defecate (as do all living creatures, after their own fashion.) Divine and supernatural beings are not (necessarily) burdened by this biological function. If it lives, it poops; if it poops, it’s alive. (Silly as that may sound, it is also profound).

The Trickster, by making use of these facts, is again reminding us of what we understand being human to mean, what we value about health and hygiene, why becoming complacent about them is detrimental, not only to the individual, but to the collective, as well.

In the guise of the Messenger/Imitator of the Gods, the Trickster reminds us not to become overconfident in our abilities. Doing something well is, indeed, an ability to be proud of, but falling into the trap of thinking you “can do no wrong” will always end in disaster.

Think of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, who, having witnessed the outward trappings of their master’s actions, believe that they, too, can achieve the same results. Copying only the superficial aspects of the Sorcerer’s endeavors, the Apprentice brings about results – disastrous ones which it then finds itself unable to control or eradicate.

This happens at the collective level, as well, as mentioned above: “group-think” can set in within a group when it has a few spectacular successes and thus loses sight of its own fallibility. And when the luck turns (and it always turns), the consequences are more disastrous the more arrogance that was indulged.

This has been seen so many times in history, when a charismatic leader has ostentatiously overcome a long-standing difficulty (to everyone’s delight), and then surrounds themselves with “yes-men”, who flatter the leader’s ego for their own ends and are unwilling to point out flaws in plans or potential negative consequences of policies, for fear of reprimand or ostracization.

Niccolò Machiavelli summed this up tidily when he wrote in The Prince, “The first method for estimating the intelligence of a ruler is to look at the men he has around him,” and “There is no other way to guard yourself against flattery than by making men understand that telling you the truth will not offend you.”24 Forget these at your peril; the Trickster will take you down a peg or two, just on principle.

All of this, of course, results in the Trickster’s status with both gods and society being unstable and suspect. This is natural; as the saying goes, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

This can lead to some confusion. Take Loki in the Norse tradition, for instance. He’ll engage in some truly atrocious act which disrupts, disorders, destroys the serenity of both Heaven and Earth, and then is usually forced to put to rights what he has upset. But, then, the reader turns the page to read the next myth, and there is Loki at his ease among the other gods, as if nothing untoward ever happened. One finds oneself asking, “Do you people never learn?”

What is important here is to remember that the Trickster is an archetype, taken on by whichever character will most effectively exercise it for the needs of the story at hand. As mentioned before, just because Loki makes an appearance, don’t automatically assume that the Trickster has appeared. Take careful note of his actions; while Loki most often carries the Trickster archetype, he may just as easily play the role of the Heroic, the Mentor, or even the Damsel. What is usual is not what is required. (And the Trickster uses this shortsightedness against you, too.)

In the sense that the Trickster archetype is a personification of Murphy’s Law that “anything that can go wrong will go wrong”, its presence and activities are a natural part of life. Confounding, disappointing, saddening, irritating, infuriating, yes; but shout at the wind and it will fill your mouth with sand.

In this way, the Trickster can teach us stoicism; accepting that things are sometimes not going to go our way, and the trick (pun intended) is to make the best of whatever befalls, correct what can be corrected, and get on with the business of life.

This is not to say that we should be nihilistic, by any means. Simply surrendering to the whims of fate and taking no action on our own behalf is quite the opposite message from what the Trickster conveys. Channeling Dylan Thomas, the Trickster exhorts us, “Do not go gentle into that good night.”25

Composite Tricksters

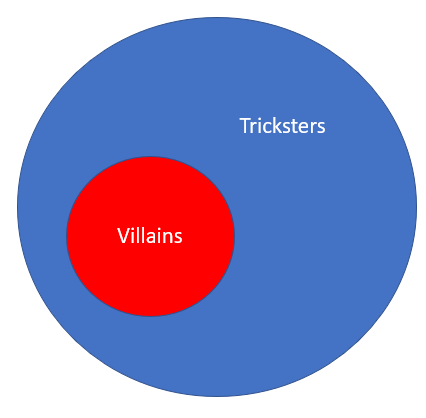

The Trickster, by its very nature, may easily combine with literally any other archetype, and frequently does. Joseph Campbell was fond of citing instances of the Trickster Heroic, and this is probably the most commonly found example. Because all Villains are Tricksters (but not all Tricksters are Villains see figure 10.2), it is often necessary for the Heroic to be more tricky than the Villain in order to get the upper hand in defeating them.

However, we see Trickster Mentors, as well. When Jedi Master Yoda makes his first appearance in The Empire Strikes Back,26 he is behaving as a Trickster Mentor, pretending to be simpler in character than he actually is, and testing Luke’s patience and compassion before agreeing to take him on as an apprentice.

Sometimes we see the Trickster Damsel, when the character who appears to need rescuing is, in fact, perfectly fine. Conversely, we might see the Damsel Trickster, in which the character needing rescuing pretends to be more helpless than they actually are.

The Most Human of the Archetypes

This is why there is profound truth in saying that the Trickster is the most human of all the archetypes. The Trickster literally exhibits every quality, admirable and deplorable, of human nature. Every single person has asked themselves at one time or another, “Why did I say that?” or “Why did I do that?” We all have more than once acknowledged (to ourselves, if not to others) that we are sometimes our own worst enemy.

And, yet, if we listen to the Trickster in ourselves, we learn valuable lessons. Lessons about who we are, who we’d like to be, where we fit in among our family, peers, community, the universe-in-general.

The great lesson of the Trickster is that “to err is human”;27 that learning happens as much by failure as by success – if we are open to the learning, if we are humble enough to submit to the lesson.

The Trickster reminds us that we are fallible; the Heroic reminds us that we can do better.