Theories and Evidence-Based Practices in Early Childhood Education

|

Student Outcomes |

Colorado Standard Competencies |

|

Evidence-based practices

History and theories in early childhood

|

Demonstrate basic knowledge of national, state, and local regulatory agencies and quality initiatives

|

Vocabulary Standard Competency: Explain basic early childhood and early childhood special education terminology |

| ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences related to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance abuse as adults

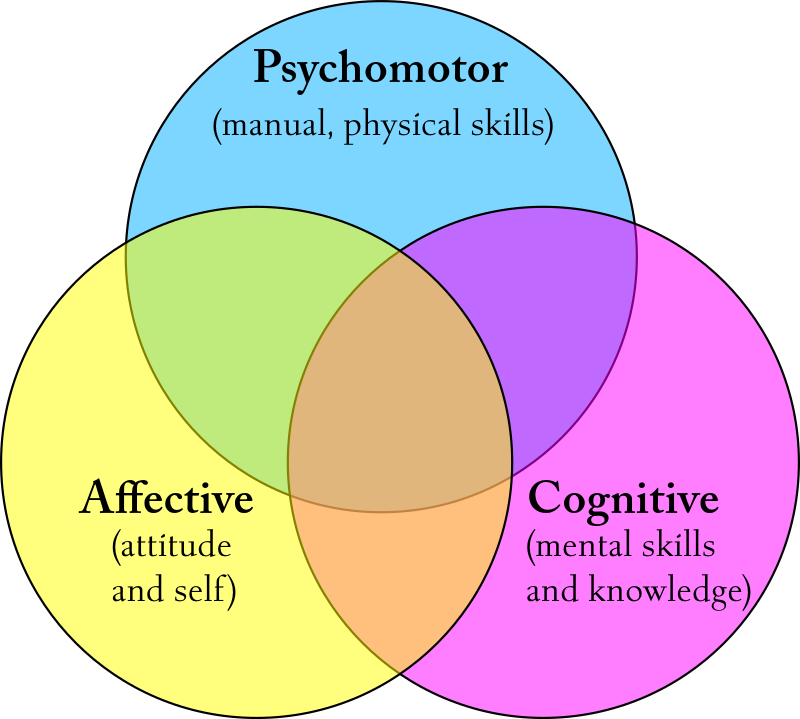

Affective Development: Our emotions, social interactions, personality, creativity, spirituality, and relationships Attachment Theory: Tendency for infants to become emotionally close to certain individuals and calm while in their presence Cognitive or Intellectual Development: Our thoughts and how our brain processes information, as well as utilizes language Physical Development: Gross motor, fine motor, perceptual motor Psychomotor: Gross motor, fine motor, and perceptual motor Theory: A supposition or system of ideas that explains principles on which the practice of an activity is based |

Introduction

This chapter goes deeper into the developmental and learning theories that guide our practices with young children. The theories presented help us better understand the complexities of human development. We conclude the chapter looking at some of the current topics about children’s development and inform and influence our field and provides us with valuable insight into the whole child – physically, cognitively, and affectively.

Theory and Why It’s Important

Human development is divided into 3 main areas: Physical, Cognitive, and Affective. Together these address the development of the whole child. All three areas of development are of critical importance in how we support the whole child. For example, if we are more concerned about a child’s cognitive functioning we may neglect to give attention to their affective development. We know that when a child feels good about themselves and their capabilities, they are often able to take the required risks to learn about something new to them. Likewise, if a child is able to use their body to learn, that experience helps to elevate it to their brain.

Theories help us to understand behaviors and recognize developmental milestones so that we can organize our thoughts and consider how to best support a child’s individual needs. With this information, we can:

- Plan and implement learning experiences that are appropriate for the development of that child (called, “developmentally appropriate practice, which is discussed more later in this chapter)

- Set up engaging environments, and most importantly,

- Develop realistic expectations based on the child’s age and stage of development.

Theories for the underlying “principles’ that guide our decisions about children in our care – how to best support them as they learn, grow, and develop – have been proposed by scientists and theorists who studied human development extensively. Here are a few questions developmental theorists have considered:

- Is development due to maturation or due to experience? This is often described as the nature versus nurture debate. Theorists who side with nature propose that development stems from innate genetics or heredity. It is believed that as soon as we are conceived, we are wired with certain dispositions and characteristics that dictate our growth and development. Theorists who side with nurture claim that it is the physical and temporal experiences or environment that shape and influence our development. It is thought that our environment, our socio-economic status, the neighborhood we grow up in, and the schools we attend, along with our parents’ values and religious upbringing that impact our growth and development. Many experts feel it is no longer an “either nature OR nurture” debate but rather a matter of degree; which influences development more?

- Does one develop gradually or does one undergo specific changes during distinct times? This is considered the continuous or discontinuous debate. On one hand, some theorists propose that growth and development are continuous; it is a slow and gradual transition that occurs over time, much like an acorn growing into a giant oak tree. While on the other hand, there are theorists that consider growth and development to be discontinuous, which suggests that we become different organisms altogether as we transition from one stage of development to another, similar to a caterpillar turning into a butterfly. Let’s take a look at some theories:

Roots – Foundational Theories

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Maturational Arnold Gesell 1880 – 1961 |

All children move through stages as they grow and mature On average, most children of the same age are in the same stage There are stages in all areas of development (physical, cognitive, language, affective) You can’t rush stages |

There are “typical” ages and stages Understand current stage as well as what comes before and after Give many experiences that meet the children at their current stage of development When child is ready they move to the next stage |

|

Ecological “Systems” Urie Bronfenbrenner 1917 – 2005 |

There is broad outside influence on development (Family, school, community, culture, friends ….) There “environmental” influences impact development significantly |

Be aware of all systems that affect child Learning environments have impact on the developing child Home, school, community are important Supporting families supports children |

Branches – Topical Theories

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Psycho-Analytic Sigmund Freud 1856 – 1939 |

|

|

|

Psycho-Social Erik Erikson 1902 – 1994 |

|

|

|

Humanistic Abraham Maslow 1908-1970 |

|

|

|

Ethology/Attachment John Bowlby 1907-1990 Mary Ainsworth 1913 – 1999 |

|

|

Branches – Cognitive Theories

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

||

|

Constructivist Jean Piaget 1896 – 1980 |

|

|

||

|

Socio-cultural Lev Vygotsky 1896 – 1934 |

|

|

||

|

Information Processing (Computational Theory) 1970 – |

|

|

||

|

Multiple Intelligences Howard Gardner 1943 – |

|

|

||

Branches – Behaviorist Theories

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Classical Conditioning Ivan Pavlov 1849 – 1936 |

|

|

|

Operant Conditioning B. F. Skinner 1904 – 1990 |

|

|

|

Social Learning |

|

|

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Albert Bandura 1925 – |

|

|

Attribution: This content was created by Sharon Eyrich. It is used with permission and should not be altered.

|

Reflection What type of program do you see yourself working in, or are currently working in? What are the benefits for you? Is there a type of program that you would not be comfortable working in? |

Evidence-Based Practices That Inform Current Practice

The following is a brief overview of developmental principles that are important to our practice and explored later in this book.

Brain Functioning

In the 21st century, we have medical technology that has enabled us to discover more about how the brain functions. “Neuroscience research has developed sophisticated technologies, such as ultrasound; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); positron emission tomography (PET); and effective, non-invasive ways to study brain chemistry (such as the steroid hormone cortisol).” These technologies have made it possible to investigate what is happening in the brain, both how it is wired and how the chemicals in our brain affect our functioning. Here are some important aspects, from this research, for us to consider in working with children and families:

Rushton (2011) provides these four principles that help us to connect the dots to classroom practice:

Principle #1: “Every brain is uniquely organized”

- When setting up our environments, it is important to use this lens so we can provide varied materials, activities, and interactions that are responsive to each individual child.

Principle #2: “The brain is continually growing, changing, and adapting to the environment.”

- The brain operates on a “use it or lose it” principle. Why is this important? We know that we are born with about 100 billion brain cells and 50 trillion connections among them. We know that we need to use our brain to grow those cells and connections, or they will wither away. Once they are gone, it is impossible to get them back.

- Children who are not properly nourished, both with nutrition and stimulation suffer from deterioration of brain cells and the connections needed to grow a healthy brain.

- Early experiences help to shape the brain. Attunement (which is a bringing into harmony) with a child, creates that opportunity to make connections.

Principle #3: “A brain-compatible classroom enables connection of learning to positive emotions.”

- Give children reasonable choices.

- Allow children to make decisions. (yellow shovel or blue shovel, jacket on or off, etc.)

- Allow children the full experience of the decisions they make. Mistakes are learning opportunities. (F.A.I.L. – First attempt in learning). Trying to do things multiple times and in multiple ways provides children with a healthy self-image.

Principle #4: “Children’s brains need to be immersed in real life, hands-on, and meaningful learning experiences that are intertwined with a commonality and require some form of problem-solving.”

- Facilitate exploration in children’s individual and collective interests.

- Give children the respect to listen and engage regarding their findings.

- Give children time to explore.

- Give children the opportunity to make multiple hypotheses about what they are discovering.

Developmentally Appropriate Practices

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), one of the professional organizations in the field of early childhood education, has recently updated their position statement on developmentally appropriate practice. You can explore this more at NAEYC Developmentally Appropriate Practice Position Statement. There are three core considerations of Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP):

-

Fig 2.2 Photo by Yan Krukau via Pexels. Commonality—Current research and understandings of processes of child development and learning that apply to all children, including the understanding that all development and learning occur within specific social, cultural, linguistic, and historical contexts. It is important to acknowledge that much of the research and the principal theories that have historically guided early childhood professional preparation and practice have primarily reflected norms based on a Western scientific-cultural model. As a result, differences from this Western (typically White, middle-class, monolingual English-speaking) norm have been viewed as deficits, helping to perpetuate systems of power and privilege and to maintain structural inequities. Increasingly, theories once assumed to be universal in developmental sciences, such as attachment, are now recognized to vary by culture and experience.

- Individuality—The characteristics and experiences unique to each child, within the context of their family and community, which have implications for how best to support their development and learning. Each child reflects a complex mosaic of knowledge and experiences that contributes to the considerable diversity among any group of young children. These differences include the children’s various social identities, interests, strengths, and preferences; their personalities, motivations, and approaches to learning; and their knowledge, skills, and abilities related to their cultural experiences, including family languages, dialects, and vernaculars. Children may have disabilities or other individual learning needs, including needs for accelerated learning. Sometimes these individual learning needs have been diagnosed, and sometimes they have not.

- Context—Everything discernible about the social and cultural contexts for each child, each educator, and the program as a whole. Context includes both one’s personal cultural context (that is, the complex set of ways of knowing the world that reflect one’s family and other primary caregivers and their traditions and values) and the broader multifaceted and intersecting (for example, social, racial, economic, historical, and political) cultural contexts in which each of us live. In both the individual- and societal- definitions, these are dynamic rather than static contexts that shape and are shaped by individual members as well as other factors.

What does this mean?

Utilizing the core components of DAP is important as practitioners of early learning. Here are some things to consider:

- Knowledge about child development and learning helps us to make predictions about what children of a particular age group are like typically. This helps us to make decisions with some confidence about how we set up the environment, what learning materials we use in our classrooms, and what are the kinds of interactions and activities that will support the children in our class. In addition, this knowledge tells us that groups of children and the individual children within that group will be the same in some ways and different in other ways.

- To be an effective early childhood professional, we must use a variety of methods – such as observation, clinical interviews, examination of children’s work, individual child assessments, and talking with families so we get to know each individual child in the group well. When we have compiled the information we need to support each child, we can make plans and adjustments to promote each child’s individual development and learning as fully as possible.

Each child grows up in a family and in a broader social and cultural community. This provides our understanding of what our group considers appropriate, values, expects, admires, etc. (think Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory and Vygotsky’s Socio-Cultural Theory). These understandings help us to absorb “rules” about behaviors:

- How do I show respect in my culture

- How do I interact with people I know well, and people I have just met

- How do I regard time and personal space

- How should I dress

When young children are in a group setting outside their home, what makes the most sense to them, how they use language to interact, and how they experience this new world depend on the social and cultural contexts to which they are accustomed. Skilled teachers consider such contextual factors, along with the children’s ages and their individual differences, in shaping all aspects of the learning environments. More information about DAP will come in later chapters.

Identity Formation

Who we are is an especially important aspect of our well-being. As children grow and develop, their identity is shaped by who they are when they arrive on this planet and the adults and peers whom they interact with throughout their lifespan. Many theories give us supportive evidence that helps us to see that our self-concept is critical to the social and emotional health of human beings. (ex. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory, John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory, etc.) As early childhood professionals, we are called upon to positively support the social/emotional development of the children and the families that we serve. We do this by:

- Honoring each unique child and the family they are a part of

- Acknowledging their emotions with attunement and support

- Listening to hear not to respond

- Providing an emotionally safe space in our early childhood environments

- Recognizing that all emotions are important and allowing children the freedom to express their emotions while providing them the necessary containment of safety

Our social-emotional life or our self-concept has many aspects to it. We are complex beings, and we have several identities that early childhood professionals need to be aware of when interacting with the children and families in their early childhood environments. Our identities include but are not limited to the following categories:

- Gender

- Ethnicity

- Race

- Economic Class

- Sexual Identity

- Religion

- Language

- (Dis)abilities

- Age

Understanding our own identities and that we are all unique, helps us to build meaningful relationships with children and families that enable us to have understanding and compassion. Being aware (using reflective practice) that all humans are diverse and that our environments, both emotionally and physically, need to affirm all who come to our environments to learn and grow.

While we begin to form our identities from the moment we are conceived, identity formation is not stagnant. It is a dynamic process that develops throughout the life span. Hence, it is our ethical responsibility as early childhood professionals to create supportive language, environments, and inclusive practices that will affirm all who are a part of our early learning programs.

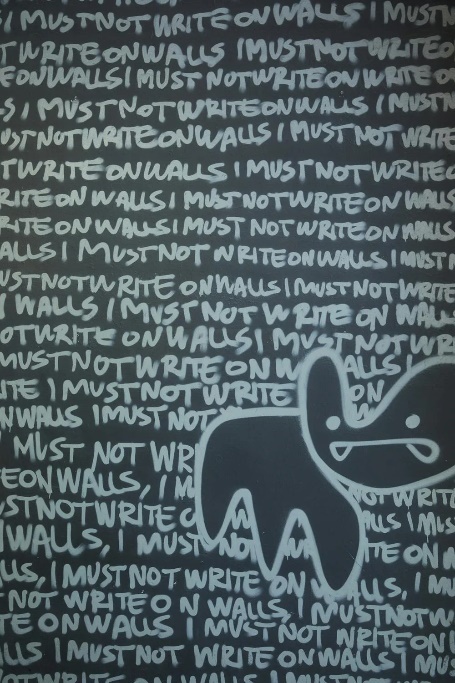

While we delve more into guiding the behavior of young children, there is evidence that when children feel supported and accepted by adults for who they are, this helps to wire and equip the brain for self-regulation. As we model regulation behavior (this is often identified as co-regulation behavior) which includes acceptance, compassion, belonging, and empathy, we are helping children to develop the regulation skills needed to get along and live in a diverse society.

Attachment

As noted in Attachment Theory, co-created by Bowlby and Ainsworth, it is clear to us that attachment is a critical component of healthy development. Our brains are wired for attachment. Many of you may have witnessed a newborn baby as they interact with their parents/caregivers. Their very survival hinges on the attachment bonds that develop as they grow and develop. Children who are not given the proper support for attachment to occur may develop reactive attachment disorder. Reactive attachment disorder is a rare but serious condition in which an infant or young child does not establish healthy attachments with parents or caregivers. Reactive attachment disorder may develop if the child’s basic needs for comfort, affection, and nurturing are not met and loving, caring, stable attachments with others are not established.

Why is this important for early childhood practitioners to know? The role of an early childhood professional is one of caregiving. While you are not the parent, nor a substitute for the parent, you do provide care for children in the absence of their parent. Families bring their children to early childhood centers for a whole host of reasons, but one thing that they share is that they trust their child’s caregivers to meet the need of their child is a loving and supportive way.

Healthy attachments begin with a bond with the child’s primary caregivers (usually their family) and then extend to others who provide care for their child. How we as early childhood professionals care and support children, either adds or detracts from their healthy attachment. Our primary role is to ensure that the needs of children are met with love and support.

It is also possible that children may enter our early childhood environment with unhealthy attachment or could have reactive attachment disorder. In this case, it is our ethical and moral responsibility to meet with the family and to provide them with resources and support that they could use to help their children to have better outcomes. As the course of study of an early childhood professional affords them with knowledge and understanding of how children grow and develop, families do not often have this foundational knowledge. It is our duty to develop a reciprocal relationship with families that is respectful and compassionate. When we offer them support, we do so without judgment.

The Value of Play in Childhood

There has been much research done in recent years about the importance of play for young children. During the last 20 years, we have seen a decline in valuable play practices for children from birth to age 8. This decline has been shown to be detrimental to the healthy development of young children as play is the vehicle in which they learn about and discover the world.

The true sense of play is that it is spontaneous, rewarding, and fun. It has numerous benefits for young children as well as throughout the lifespan.

- It helps children build foundational skills for learning to read, write and do math.

- It helps children learn to navigate their social world. How to socialize with peers, how to understand others, how to communicate and negotiate with others, and how to identify who they are and what they like.

- It encourages children to learn, to imagine, to categorize, to be curious, to solve problems, and to love learning.

- It gives children opportunities to express what is troubling them about their daily life, including the stresses that exist within their home and other stresses that arise for them outside of the home.

Trauma Informed Care

Over the last few decades, we have seen an increase in childhood trauma. Many types of trauma have a lasting effect on children as they grow and develop. When we think of trauma, we may think of things that are severe; however, we know that trauma also comes in small doses that are repeated over time.

There has been much research done to help identify what these adverse childhood experiences are. The compilation of research has identified some traumatic events that occur in childhood (0 – 17 years) that have an impact on children’s well-being that can last into adulthood if not given the proper support to help to mitigate this trauma. Here is a list of some of the traumatic events that may impact children’s mental and physical well-being:

- Experiencing violence or abuse

- Witnessing violence in the home or community

- Having a family member attempt or die by suicide

Also, there are aspects of the child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding such as growing up in a household with:

- Substance misuse

- Mental health problems

- Emotional abuse or neglect

- Instability due to parental separation or household members being in jail or prison

These adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness and substance abuse in adulthood, and a negative impact on educational and job opportunities.

Here are some astounding facts about ACEs:

- ACE’s are common. About 61% of adults surveyed across 25 states reported that they had experienced at least one type of ACE, and 1 in 6 reported they had experienced four or more types of ACEs.

- Preventing ACEs could potentially reduce a large number of health conditions. For example, up to 1.9 million cases of heart disease and 21 million cases of depression could have been potentially avoided by preventing ACEs.

- Some children are at greater risk than others. Women and several racial/ethnic minority groups were at greater risk for having experienced 4 or more types of ACEs.

- ACEs are costly. The economic and social costs to families, communities, and society total hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

Trauma Informed Care is an organizational structure and treatment framework that involves understanding, recognizing, and responding to the effects of all types of trauma. Trauma Informed Care also emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety for both consumers and providers, and helps survivors rebuild a sense of control and empowerment.

What can we do in our early childhood programs? We can help to ensure a strong start for children by:

- Creating an early learning program that supports family engagement.

- Make sure we are providing a high-quality childcare experience.

- Support the social-emotional development of all children.

- Provide parenting workshops that help to promote the skills of parents.

- Use home visitation as a way to engage and support children and their families.

- Reflect on our own practices that could be unintentionally harmful to children who have experienced trauma.

What can we do in our community? As early childhood professionals, our ethical responsibilities extend to our community as well (NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, May 2011):

- Be a part of changing how people think about the causes of ACEs and who could help prevent them.

- Shift the focus from individual responsibility to community solutions.

- Reduce stigma around seeking help with parenting challenges or for substance misuse, depression, or suicidal thoughts.

- Promote safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments where children live, learn, and play.

Final Thoughts

This chapter explored the developmental and learning theories that guide our practices with young children. This included a look at some of the classic theories that have stood the test of time, as well as the current developmental topics to give us opportunities to think about what we can do to create the most supportive learning environment for children and their families. Learning is a complex process that involves the whole child – physically, cognitively, and affectively.