Health, Safety, and Nutrition – Impact on Brain Development

|

Topical Outline |

Colorado Standard Competencies |

|

Health, safety, and nutrition

|

Describe best practices for health, safety, and nutrition for young children and apply state regulatory requirements for nutrition, health, and safety in the early childhood setting Define developmentally appropriate practices for programs serving young children

|

Vocabulary Standard Competency: Explain basic early childhood and early childhood special education terminology |

| ACES: Adverse Childhood Experiences

Axon: Part of the neuron that sends information to other cells Boundaries: How quickly a brain can develop myelin Brain Stem and Midbrain: Lower part of the brain concerned with survival Cerebellum: Part of the brain concerned with coordination Cortex: Outer part of the brain concerned with higher level thinking Cortical Modulation: Ratio of function in brain areas Cortisol: Hormone released during stress Dendrite: Part of the neuron that receives information from other cells Distress: Negative stress Emotional Intelligence: 5 specific skills related to understanding feelings of self and others and using them to make positive life decisions Enriched Environment: Stimulating, challenging, supportive and loving environment Eustress: Positive stress Frontal Lobe: Part of the cortex that processes sensory and motor information Limbic system: Mid-part of the brain concerned with emotions and memory Mindfulness: Being aware of your body and surroundings in the current moment Myelination: Protective fatty coating on the mature neuron Neurotransmitters: Chemical messengers that transmit information between neurons Occipital Lobe: Part of the cortex that processes vision Parietal Lobe: Part of the cortex that processes sensory information Plasticity: How easily the brain can change itself. It is more plastic in the youngest years Prefrontal Lobe: Part of the cortex that processes critical thinking, problem solving and executive function and self-regulation Pruning: Reducing the number of connections and neurons in the brain Resilience: Ability to overcome early hardships Stress: Physical, chemical, or emotional factor that causes bodily or mental tension Synaptic Gap: Tiny space between neurons Temporal Lobe: Part of the cortex that processes hearing, speech, and language Thalamus: Acts like a gate for sensory information coming into the brain Window of Opportunity: Times when the brain is best suited to learn a task |

Introduction

We study the brain to get a better understanding of children’s development, disabilities, to recognize the giftedness in all of us, and to improve programs and policies for children and families. We will explore functions of the brain and the impact of stress and trauma. Finally, we will explore application of brain development to the field of early childhood.

The brain is the only organ to study itself. It is critical to understand how the brain develops and what is necessary to maintain its health because it informs and impacts everything we do in our lives, especially when working with children. As we will learn, the brain develops quickly in the early childhood years but continues to change throughout our lives. When we understand the brain, we understand the power and impact of positive early childhood experiences. We also will come to understand the impact on young brains from toxic stress and abuse and what we need to do in order to prevent this. Building healthy brains from the start helps everyone.

Brain Development

|

|

Reflection The purpose of learning basic information about brain development is to understand the theory that informs everything we do when working with children.

|

Basic Brain Facts

At the cellular level, the brain is made up of 86 billion nerve cells called neurons that regulate cognitive activity. There are at least 10 times more support cells, called glial cells. Once it was thought we had 100 billion nerve cells, but newer research has demonstrated it is actually 86 billion (BrainFacts/SFN, 2018). Neurons communicate with each other through billions of connections in an electrochemical process. There are about 500 trillion connections in the adult human brain.

Although there has long been a debate about whether we are more impacted by nurture (our environment) or nature (our individual biology), we now understand that it is actually a unique combination of both. While neither nature nor nurture fully explains what makes us human, we do know that it is a complex relationship between the two. Biology and genetics may provide the potential, but our social environment can shape our ability to access that potential.

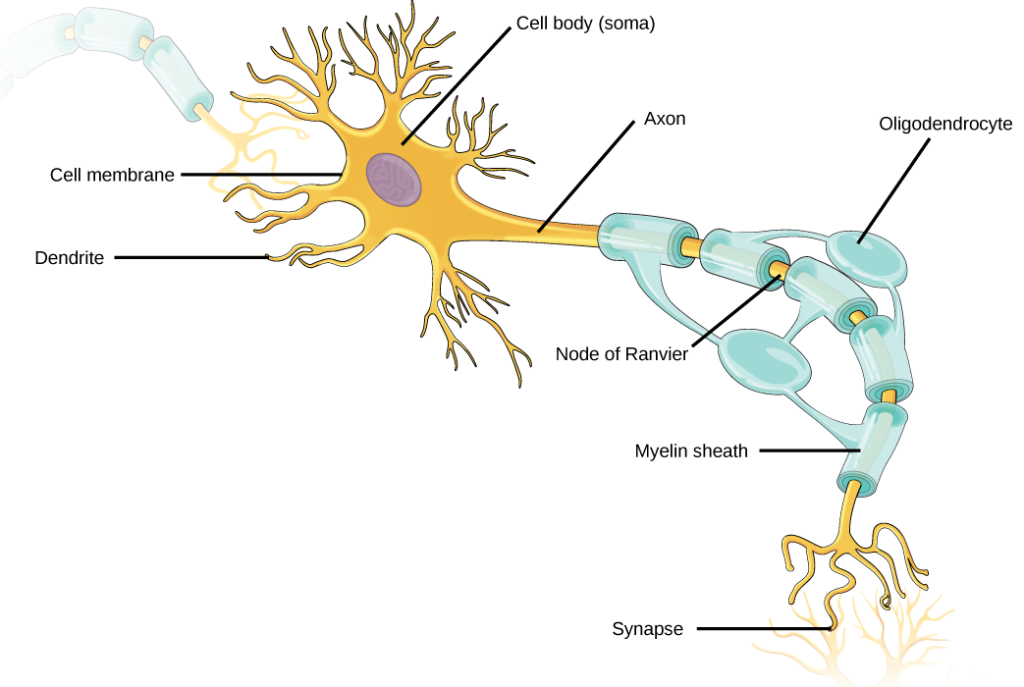

Neurons

Neurons transmit information between each other through axons and dendrites using the synaptic gap to exchange neurotransmitters. The axon sends a message through a series of electrical impulses called the action potential. When the impulse reaches the end of the axon the electrical activity ceases. A chemical process takes place in the form of neurotransmission. If the message is “transmitting” an electrical charge is triggered in the next neuron. That neuron’s dendrite receives the message and electrically sends it through the axon to the next neuron. The process repeats until the message has reached its destination.

Neurotransmission

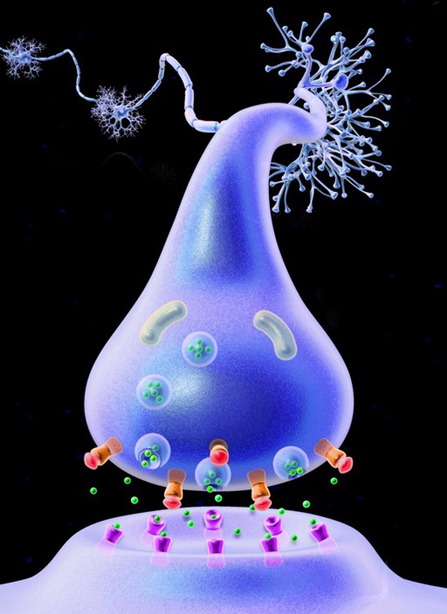

When the electrical impulse that carries information reaches the end of a neuron’s axon, they are stopped at the tiny synaptic gap that separates them from the receiving neuron. The circuit is broken. Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers secreted at the synapse that have the potential to continue the circuit and transmitting information between neurons.

Without neurotransmitters the brain could not process information or send out instructions to run the rest of the body. They affect the formation, maintenance, activity and longevity of synapses and neurons. Neurotransmitter molecules are produced within a specific type of neuron (different neurons are specialized in different neurotransmitters) and stored in tiny sacs known as vesicles. When an electrical signal reaches the vesicles, they release their neurotransmitters into the synaptic gap.

Each type of neurotransmitter has a unique shape that acts like a key. Released neurotransmitters attempt to attach to receptor sites (usually on the receiving neuron’s dendrites). Each receptor site is shaped like a lock that will fit only certain types of neurotransmitters. If the key fits, the neurotransmitter will send a message to turn on a receiving neuron- excitatory or off – inhibitory.

When a neurotransmitter’s job is done, the receptors release the molecules, which are either broken down or recycled. Each neurotransmitter has a very specialized function. Ligands or neurotransmitters can be broken down into categories: classical neurotransmitters, peptides, soluble gases, or steroids (hormones). Some neurotransmitters carry emotional information that impact our mood, outlook on life and behavior. For example, Cortisol has an impact on our stress response system.

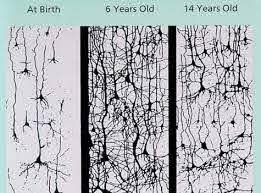

Babies are born with an estimated 86 billion brain cells. We create new connections, in the form of neural pathways, in response to our active engagement in stimulating experiences. In the first few years of life more than 1 million new neural connections form every second (Center for the Developing Child). Most neural pathways are created after birth as a result of stimuli coming from the environment that the child interacts with through the senses.

Each time the brain responds to a similar stimulus there is an increased propensity for the neurons to reconnect along the same pathway. Connections grow in a brain when experiences are repeated over and over or when an experience triggers a strong emotional reaction. The brain becomes hard wired to respond along established pathways.

Neurons physically change as a result of this activation. Neurons grow new dendrite branches and receptor sites allowing the brain to process information more effectively and efficiently in more areas of the brain. The brain changes in response to experience by making connections with new input to what is already known and in place. The brain learns by recognizing patterns to make sense of new experiences. For example, when a baby tracks a toy with their eyes while grasping at it with their hand their visual and motor pathways are connecting and growing stronger. Experience sculpts the brain!

The most active period for creating connections is in the early years of life, but new connections can form throughout life. After this rapid proliferation early on, unused brain cells and connections wither away in a process called pruning. Pruning is necessary in order to make room for the pathways the child needs most to survive in their world. Creating room also has the function of making the remaining pathways more efficient. Think of how pruning a fruit tree is essential to make room for new growth and fruit to mature. Pruning too many neurons that are important will decrease the brain’s efficiency. Most intensive pruning happens between the ages 7 and 12 but is happening in some form throughout life, starting at about 8 months. The intensity of the pruning is dependent on which area of the brain is being affected at the time.

Plasticity

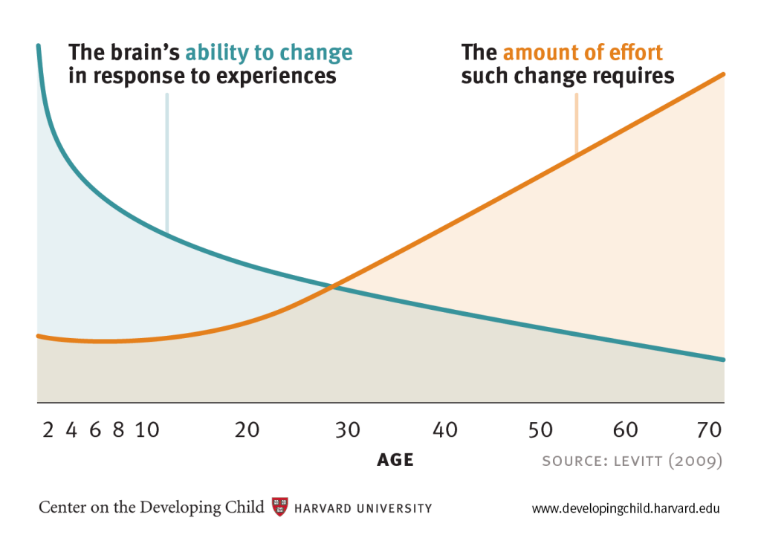

Plasticity is the term that describes the ease with which the brain can change itself. Our genes provide the blueprint, and our experiences are the architect. Which genes get turned on or off is determined by our experiences and environment. The brain’s pathways strengthen as they are used. As stated above, the neurons that are not used are subject to pruning, so it is a literal “use it or lose it” scenario. There is a remarkable increase in synapses during the first year of life. At birth we start with around 50 trillion connections, by 3 years we have around 1,000 trillion connections and as adults we have about 500 trillion connections. The brain is most plastic early in life, and it is easier to influence a baby’s brain than try to rewire parts of it in the later years.

Windows of Opportunity

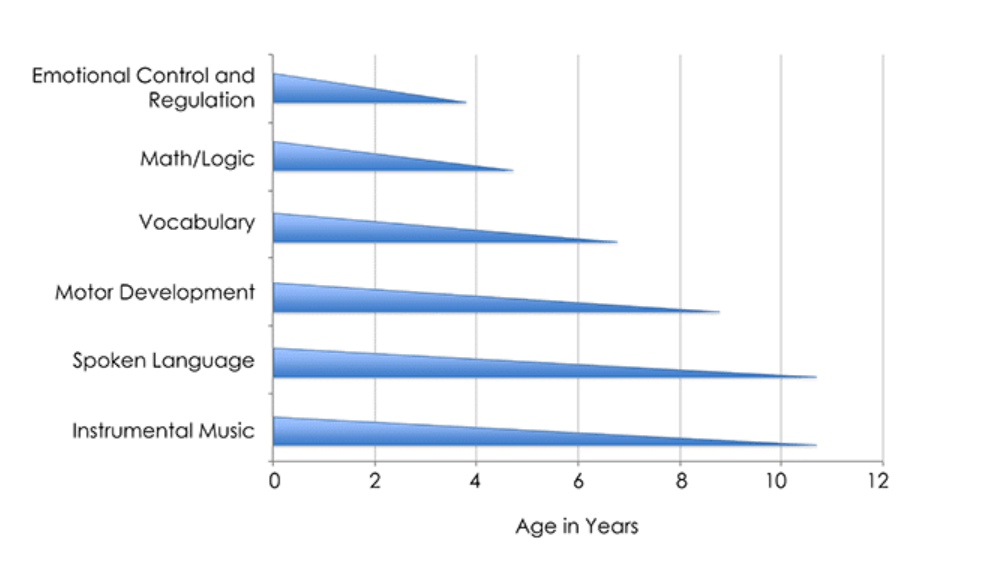

There are some windows of opportunity in the brain for optimal growth. During certain stages of brain growth, parts of the brain become much more active in response to what the senses absorb, growing and learning faster than at any other time in life. Children need the right experiences at the right time for their brains to fully develop in these areas. Sight is one of these windows of opportunity. If the eyes are deprived of sensory input early in life the neurons poised to connect for visual pathways reassign and sight will not develop. Most windows of opportunity are only optimal times and not absolutes. Every child is on their own timetable and so the age they reach the window will vary.

It is important to remember that windows of opportunity are times when the brain is the most responsive for optimal development. When developmental stages are interrupted or skipped, or an injury of any degree is experienced, some sensory-motor and cognitive functions may be impaired or missing. For most functions it is never too late to grow new neurons and pathways, but it gets increasingly harder to do this as the brain ages. Early intervention is key to helping the brain get back on track for optimal development. The human brain has a remarkable ability to heal. Windows don’t “slam shut” but slowly close as we age, never really shutting for good.

Children need active involvement in a stimulating, challenging and loving environment to cause the brain to grow and flourish. Passive involvement, isolation and an impoverished environment diminish the brain.

Enriched Environments

What is included in an enriched environment for the brain?

- Sleep: Babies, children, and adult’s brains need adequate sleep. Sleep is when the brain renews itself and cements learning.

- Nutrition: Brains need proper nutrition with the right types of fat, protein, fruits, and vegetables. We are quite literally what we eat, and our brain can only function as well as the fuel we give it. Foods high in refined sugar are toxic for a growing brain. The American Association of pediatrics recommends limiting the amount of sugar children consume each day to no more than 6 teaspoons for ages 2 and older. A typical child consumes more than triple that on average. (Jenco 2016) A great resource to make sure you are giving kids a balanced diet is MyPlate by the USDA.

- Water: It is also essential for the brain and body to stay hydrated. Encouraging children to drink water instead of juice is important to reduce the amount of sugar they are consuming while hydrating their brain. WebMD suggests the following: Toddlers need 2-4 cups, 4-8 years need 5 cups, 9-13 year need 7-8 cups and over 14 need 8-11 cups. (WebMD, 2016).

- Safety: Children need a safe environment with appropriate boundaries. Giving kids the freedom to explore while making sure that the environment is free from toxins and hazards helps young brains grow. They need the chance to interact with interesting materials and be given clear guidance about what is safe and not safe. We can think of boundaries as a fence we provide that surrounds the child and enlarges as they mature. The fence keeps them safe but within it they are free to explore and push against the boundary, so they know they are safe.

- Role Models: Another important part of an enriched environment is positive role models and guidance. Adults should model the lifestyle and behavior they want from children. Eating healthy, drinking water, getting adequate sleep and exercise, and modeling emotional intelligence and growth mind set skills are all part of this. If the adults around children strive to keep their brains healthy chances are kids will follow in suit. Positive guidance lets the child know they are safe, and that behavior is a learned skill just like tying their shoe. Both require activation of neurons to build strong pathways.

- Exercise: Young brains do best when media is limited, and they have daily exercise with time in nature. Movement of bodies creates an increase in the oxygen and blood flow to the brain, helping to keep it healthy at any age. Nature provides the brain with a complex bath of sensory input that will strengthen pathways and connections in a way that can’t be replicated indoors. In addition, our brains need down time and unstructured play. Down time for brains allows children to follow their own interests and develop mastery over skills they are learning. It is through unstructured play time that children feel free to learn about their world and strengthen their abilities. Young brains need practice repeating positive developmentally appropriate experiences with caring adults supporting them.

- Stress: It is important not to stress the child by pushing them to do things they are not ready for or providing an overstimulating environment. The best approach is to follow the lead of the child and focus on their interests and unique timetables.

The child’s brain is not a smaller version of an adult brain. Neurons are still moving into position. As the brain develops, neurons migrate from the inner surface of the brain to form the outer layers. Immature neurons use fibers from cells called glia as highways to carry them to their destinations.

Recommended Sleep

Recommended Sleep

|

Age Range |

Recommended Hours of Sleep |

|

Newborn (0-3 months) |

14-17 hours including naps |

|

Infant (4-11 months) |

12-15 hours including naps |

|

Toddlers (1-2 years) |

11-14 hours including naps |

|

Preschool (3-5 years) |

10-13 hours including naps |

|

School-age (6-13 years) |

9-11 hours |

|

Teens (14-17 years) |

8-10 hours |

|

Young Adults (18-25 years) |

7-9 hours |

|

Adults (26-64 years) |

7-9 hours |

|

Older Adults (65 or more years) |

7-8 hours |

Myelination

Mature neurons have axons that are coated by a fatty layer called myelin, the protective sheath that covers communicating neurons. Myelin acts in two ways: it provides substance for the brain and insulates the cells. The myelination of axons speeds up the conduction of nerve impulses, through an ingenious mechanism that does not require large amounts of additional space or energy. Areas of the brain do not function efficiently until they are fully myelinated. Babies are born without much myelin.

Myelin is composed of 30% protein and 70% fat. One of the most common fatty acids in myelin is oleic acid, which is also the most abundant fatty acid in human milk, and we should strive to include this in our diets. Monounsaturated oleic acid is the main component of olive oil as well as the oils from almonds, pecans, macadamias, peanuts, and avocados. According to Harvard Health, how the brain begins is how it stays for the rest of life, so it is important to make sure nerves grow, connect, and get covered with myelin.

In order to protect a baby’s unmyelinated neurons, it is important to never shake a baby. Although there may be no outside sign of damage the neurons get whipped around and have no protection from myelin. It is also essential that children get proper kinds and amounts of fats and oils. Breast milk contains a fat almost identical to the fat in myelin, so if possible, mothers should nurse during the first year of life.

How Brain Development Connects with Early Childhood

|

|

Reflection What are some ways that learning about brain development can connect to the work you do with young children? How will you incorporate what you’ve learned about brain development into your classroom? |

Media and Screen Time

The developing brain needs positive interactions with caring adults in an enriched environment for optimal growth. Interactions with media or screens can be detrimental to this development as it deprives the brain of multisensory interactions which are necessary for neuronal growth. Media includes phones, television, computers, and anything with a screen. The Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recommended limited media for all ages and an emphasis on in person interactions. Research by AAP has found that using “A healthy Family Media Use Plan, that is individualized for a specific child, teenager, or family can identify an appropriate balance between screen time/online time and other activities, set boundaries for accessing content, guide displays of personal information, encourage age-appropriate critical thinking and digital literacy, and support open family communication and implementation of consistent rules about media use.” (AAP, 2016)

The American Academy of Pediatrics also shares important information about why limited media use is important. Overuse of digital media may place your child at risk of:

- Not enough sleep. Young children with more media exposure or who have a TV, computer, or mobile device in their bedrooms sleep less and fall asleep later at night. Even babies can be overstimulated by screens and miss the sleep they need to grow.

- Delays in learning and social skills. Children who watch too much TV in infancy and preschool years can show delays in attention, thinking, language, and social skills. One of the reasons for the delays could be because they interact less with parents and family. Parents who keep the TV on or focus on their own digital media miss precious opportunities to interact with their children and help them learn. See Parents of Young Children: Put Down Your Smartphones.

- Obesity. Heavy media use during preschool years is linked to weight gain and risk of childhood obesity. Food advertising and snacking while watching TV can promote obesity. Also, children who overuse media are less apt to be active with healthy, physical play.

- Behavior problems. Violent content on TV and screens can contribute to behavior problems in children, either because they are scared and confused by what they see, or they try to mimic on-screen characters.” (AAP, 2019)

Emotional Intelligence/Social Emotional Development

One of the first brain constructs to develop are those that process emotion and are laid down before birth. Early emotional experiences form a kind of template that continued emotional development is built on. These experiences have a disproportionate importance in organizing the mature brain. Emotions develop in layers, each more complex than the last as the child responds to emotional environment. Emotional learning becomes ingrained as experiences are repeated over and over.

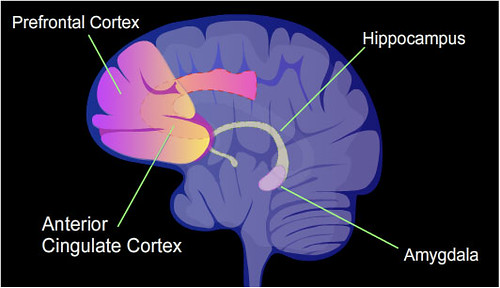

The Prefrontal cortex regulates emotional responses and are developed and connected with the limbic system early, between 8 and 18 months of life. These neural pathways in the limbic system and prefrontal lobes provide the framework for emotional intelligence.

Peter Salovey, a Yale Psychologist, and John Mayer, a University of New Hampshire psychologist, first proposed that we also have emotional intelligence. Daniel Goleman popularized this concept in his book “Emotional Intelligence” (Goleman, 1995)

Emotional Intelligence (EI) consists of a person’s abilities in 5 main areas or domains (Goleman, 2005):

- Self-Awareness –The ability to recognize or know feelings as they are happening and using them to make life decisions with which you can live. This includes pleasant, unpleasant, and multiple emotions at once. It is critical we teach children about all their feelings and give them a wide range of emotional labeling (see figure 3)

- Mood Management –The ability to manage distressing emotions in appropriate ways to maintain our wellbeing

- Self-Motivation –The ability to persist in the face of setbacks and channeling your impulses in order to pursue your goals

- Empathy – The ability to recognize and share another’s feelings

- Social Arts – The ability to interact with others in positive and socially acceptable ways.

Emotional Intelligence is important because studies with children have shown that higher emotional intelligence is a better predictor of success than IQ. Kids who participate in social emotional learning (SEL) programs at school had significantly improved social and emotional skills, attitudes, behavior, and academic performance (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor and Schellinger, 2011).

In order for emotional intelligence to develop, children need to feel secure and that their needs for survival are being met. The fundamental task of an infant is how to get their needs met in their world. Children also need to feel loved and emotionally secure. It is essential that they have a consistent, nurturing relationship with the same caregiver early in life in order to develop a secure attachment.

Attunement is also critical to the development of EI; this is when a child’s inner feelings are accepted and mirrored back to them by caregivers. The brain uses the same pathways to generate an emotion as it uses to respond to it, so these experiences strengthen their emotional intelligence pathways. If emotions are repeatedly met with indifference or clashing responses, they may fail to strengthen or be eliminated. Feelings mirrored back to children help them develop self-awareness, the foundation of Emotional Intelligence.

A child’s ability to regulate their emotions (calm down or self sooth) is built when they feel soothed by their caregivers. It is accepted that a baby does not have the ability to self –sooth until 6-8 months. It is not recommended that babies “cry it out” until after this time because even if they do become quiet, stress chemicals, like cortisol, stay active in their brain and inhibit optimal development of the stress response pathways.

Stress

Stress is defined as a “physical, chemical, or emotional factor that causes bodily or mental tension and may be a factor in disease causation” (Merriam-Webster). There are two types of stress: positive stress or eustress and negative stress or distress. Which type of stress, how much and how we interpret it all impact how damaging stress is to our systems.

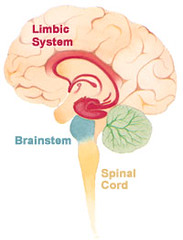

Neural pathways run from the eyes, ears, and other sense organs to a central clearing house deep in the brain called the thalamus. The thalamus works with the hypothalamus and amygdala to pass on the information to the higher levels of the cortex. They act like a gate to pathways that run to the cortex and are activated by how we feel about the information being processed by the limbic system. (Zhang, Li Steffens, Guo, and Wang 2019).

When we experience a positive emotion, are actively engaged, or appropriately challenged, while retaining a sense of control, we experience eustress. The thalamus “opens the gate” to the cortex where higher level thinking takes place. This is referred to as “upshifting.”

When a threat is perceived, we experience distress. The thalamus sends a message to the amygdala that there might be danger. The amygdala, acting as an alarm company, activates a cascade of chemicals (neurotransmitters and hormones) involved in the stress response: freeze-flight-fight. This distress closes the gate to the main road to the cortex and the brain downshifts to the lower survival brain. At the same time, another slower pathway moves up to the cortex- like a detour route. We can now access the prefrontal lobes to modulate our emotional reactions. This helps us make a rational decision about how to respond to an emotional trigger.

Children need experiences that help them develop a strong stress-response system so that they recover from stressful situations quickly and build stronger pathways between the limbic system and prefrontal lobe in their brain. The main way adults can help build this healthy stress response system is a process called “serve and return.” The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University suggests 5 steps to build positive brain pathways:

- Notice the serve and share the child’s focus of attention. It is important to pay attention to what the child is focused on and follow their lead on the interaction.

- Return the serve by supporting and encouraging. Offer comfort when they are distressed, play with them, be curious about what they are doing. Mirroring their thoughts and feelings let them know they are seen and understood.

- Give it a name! Name what a child is seeing, doing, or feeling will make important language connections in their brain, even before they can talk or understand your words. This helps them understand the world around them.

- Take turns…and wait. Keep the interaction going back and forth. Make sure to take time to let the child respond to you as you take turns interacting. They need time to form responses as they are learning so many things at once.

- Practice endings and beginnings. Sharing focus with a child helps you know when they are done. Did they turn away, fuss, or walk away? Let them take the lead and be sensitive to when they are ready to start something new.

When children are experiencing extreme amounts of stress and are not getting the positive interactions to mitigate it, they are experiencing what is known as “toxic stress.”

|

THE TAXONOMY OF STRESS The Council needed an effective way to communicate the negative effects of excessive and persistent stress on a young child’s brain and other developing organ systems. When Council members refer to stress, they describe three different levels of biological response and their impacts. |

||

|

Positive stress response is a normal part of healthy development and refers to the transient increases in heart rate and hormonal levels that occur when a child is first left with a new caregiver or is given a shot at the doctor’s office. |

Tolerable stress response refers to significant activation of the body’s “alert systems,” as might occur after the loss of a loved one or a natural disaster, in the presence of adult support. If the child is cared for by at least one responsive adult who provides a sense of security and protection, the stress response doesn’t last for an extended period of time, and the child’s brain and other organs can recover from potentially damaging effects. |

Toxic stress response is the unrelenting activation of stress response systems in the absence of adequate support or protection from adults. It can be precipitated by serious adversity, such as extreme poverty, frequent neglect, physical or emotional abuse, or maternal substance abuse and can lead to stress- related diseases or deficits in learning and behavior across the lifespan. |

|

|

|

|

Chart describing the taxonomy of stress. National scientific council on the developing child (2020)

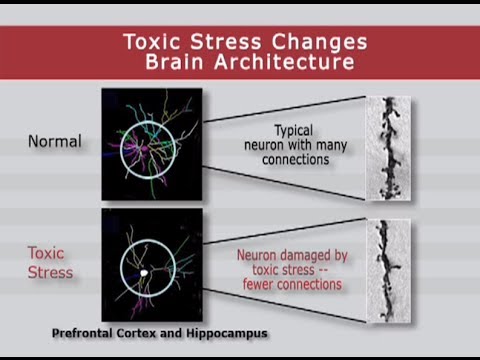

Trauma and ACEs

Too much toxic stress in a child’s life can damage the developing brain and lead to life-long problems in learning, behavior, and physical and mental health. Toxic stress can come from extreme poverty, repeated abuse, or severe maternal depression. These situations or experiences are also called Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACEs and cause a prolonged toxic stress. Many studies have confirmed the negative impact of ACEs on the health and wellbeing of children and adults. The Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University has a wealth of information about the impact of toxic stress and ACEs. There is also evidence of how racism is connected to poor outcomes for children due to the impact of toxic stress on child development. Toxic Stress impacts a growing brain’s development by causing neurons to have fewer connections in the limbic and prefrontal cortex, the areas of the brain that control emotional reactivity.

Chart of impact of toxic stress on neuron connections. Center for the Developing Child Harvard University.

Cortical Modulation

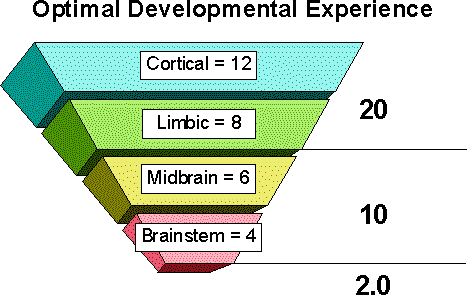

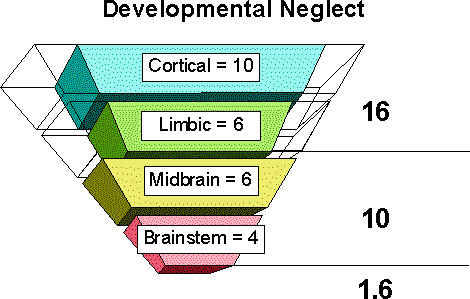

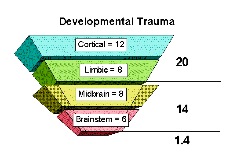

When a child experiences toxic stress or ACEs, the higher regions of the brain become less developed since the brain is constantly activating the pathways to the lower, survival regions of the brain. Dr. Bruce Perry developed a model for understanding the functioning of the layers of the brain in connection to each other called cortical modulation, specifically, how do the higher layers modulate the lower levels of the brain. He has demonstrated the decreased modulation ratio of the layers in the developing brain when impacted by ACEs.

When looking at the number of connections in each of these layers in children’s brains we see a difference in their function based on their experiences. Figure 7 shows the optimum ratio in a healthy brain. The higher levels or cortical areas of the brain have the most connections, and higher ratio. The “thinking brain” is the strongest and therefore a child would have a strong stress response system developing.

When a child is experiencing ACEs and toxic stress the ratio is less optimal. In figures 8 and 9 we see the impact on the ratios in brains experiencing neglect, trauma or both neglect and trauma. In these brains the lower regions of the brain have more connections and thus down shifting happens in the brain more readily.

The brain of a child with many adverse childhood experiences is physically smaller than that of a healthy child.

Resilience

Some children who experience ACEs and toxic stress develop brains with better ratios than others. We consider these children to have resilience. Resilience requires supportive relationships and opportunities for skill building. These relationships can be outside of the family, for example a teacher or coach, and are the active ingredient for developing resilience. If children experiencing ACEs have access to these positive experiences, their brain can reverse the ratio and develop a greater ability to manage the stress in their lives. A child’s temperament can also be a factor in developing resilience.

Trauma Informed Care and Education

Understanding how the brain develops and what can happen if children do not get positive, caring experiences helps teachers create classrooms that will benefit all children. One of the keys to creating trauma informed care is understanding what the brain needs in order for a more optimal outcome. We need to move from blaming the child to understanding them. Providing consistent care and attachment with a teacher who is loving and compassionate is essential. Classrooms must be built to allow for healthy, developmentally appropriate experiences that provide an enriched environment for young brains to flourish.

Social Emotional Learning programs in schools are helping children develop skills to build strong pathways between the limbic and cortex layers of the brain. These programs have demonstrated success in building a child’s resilience and emotional intelligence.

Colorado Health and Safety Requirements

The Division of Early Learning Licensing and Administration (DELLA) is responsible for the administration of health and safety rules and requirements for licensed child care facilities. The Department monitors programs for compliance with all rules and regulations at each licensing inspection.

These requirements include, but are not limited to:

- Building and physical premises safety, including identification of and protection from hazards that can cause bodily injury such as electrical hazards, bodies of water and vehicular traffic

- Administration of medication, consistent with standards for parental consent

- Emergency preparedness and response planning for emergencies resulting from a natural disaster, or a man-caused event (such as violence at a child care facility)

- First aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Handling and storage of hazardous materials and the appropriate disposal of bio contaminants

- Precautions in transporting children

- Prevention and control of infectious diseases, including immunization

- Prevention of and response to emergencies due to food and allergic reactions

- Prevention of shaken baby syndrome and abusive head trauma

- Prevention of sudden infant death syndrome and use of safe sleeping practices

The Division of Early Learning Licensing and Administration (DELLA) requires professionals working in child care facilities to complete training related to each health and safety requirement. Many of these trainings are currently available on-demand and free through the Colorado Shines Professional Development and Information System or other training resources.

Final Thoughts

Understanding the brain, how it develops, how it functions and what it needs for optimal development is essential in creating a developmentally appropriate early childhood classroom. Once we understand how to provide a place where children’s brains are getting what they need, we are more likely to reverse negative impacts they may be experiencing elsewhere. This chapter has given you a brief overview of brain development and function and the necessary elements a child needs in the early years and beyond.