Curriculum Through Play

|

Topical Outline |

Colorado Standard Competencies |

|

Developmentally appropriate practices Key components

Practical application

Curriculum Models in early childhood education |

Define developmentally and culturally appropriate practices for programs serving young children Practice child observation skills in early childhood program setting, including direct and indirect observation, and objective documentation |

Vocabulary Standard Competency: Explain basic early childhood and early childhood special education terminology |

|

Play Symbolic Play – play which provides children with opportunities to make sense of the things that they see (for example, using a piece of wood to symbolize a person or an object) Rough and Tumble Play – this is more about contact and less about fighting, it is about touching, tickling, gauging relative strength, discovering flexibility and the exhilaration of display, it releases energy, and it allows children to participate in physical contact without resulting in someone getting hurt Socio-Dramatic Play – playing house, going to the store, being a mother, father, etc., it is the enactment of the roles in which they see around them and their interpretation of those roles, it’s an opportunity for adults to witness how children internalize their experiences Social Play – this is play in which the rules and criteria for social engagement and interaction can be revealed, explored, and amended Creative Play – play which allows new responses, transformation of information awareness of new connections with an element of surprise, allows children to use and try out their imagination Communication Play – using words, gestures, charades, jokes, play-acting, singing, whispering, exploring the various ways in which we communicate as humans Locomotor Play – movement in any or every direction (for example, chase, tag, hide and seek, tree climbing) Deep Play – it allows children to encounter risky or even potentially life- threatening experiences, to develop survival skills, and conquer fear (for example, balancing on a high beam, roller skating, high jump, riding a bike) Fantasy Play – the type of play allows the child to let their imagination run wild, to arrange the world in the child’s way, a way that is unlikely to occur (for example, play at being a pilot and flying around the world), pretending to be various characters/people, be wherever and whatever they want to be and do Object Play – use of hand-eye manipulations and movements |

Introduction

As we have learned in previous chapters, developing relationships, as well as understanding the developmental stages and individual interests and skills of children is crucial to effective teaching. This is accomplished through interactions and both informal and formal observations with the children in our care. This information will form the cornerstone of what is called “curriculum,” which includes both the planned and unplanned experiences that occur throughout the day. This chapter will provide some of the basic concepts in a developmentally appropriate curriculum.

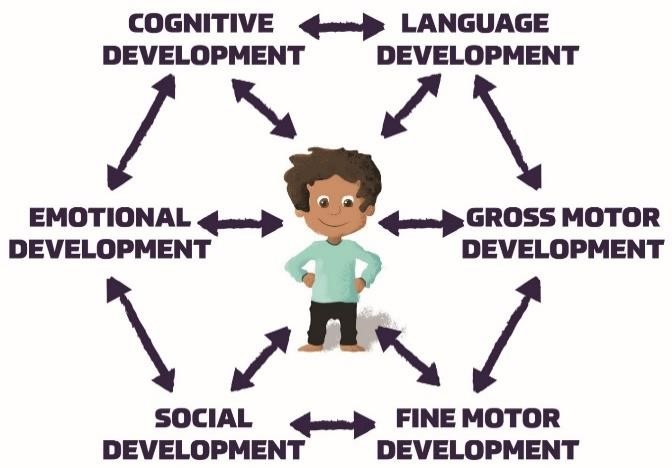

“Development” and “learning” are two integrated concepts that we promote as teachers. As children are “learning” new concepts and skills, they are fostering their “development.” Our goal is to encourage the development of the “whole child” (physical, cognitive, social, emotional, language) by providing learning experiences based on children’s interests and abilities, a concept known as “intentional teaching.”

Although children learn in an integrated manner (blending all areas of development together) these areas are often broken down for planning purposes.

The table below shows the relationship between the domains of development and concepts of learning.

|

Development |

Learning |

|

Cognitive |

Science, Technology, Math |

|

Language |

Language and Literacy |

|

Physical |

Health, Safety, Nutrition, Self-Help Skills, Physical Education |

|

Social, Emotional, Spiritual |

Social Science, Visual and Performing Arts |

Vignette

Javier and Ji are playing in the block area. They have stacked several large blocks on top of each other. Twice the blocks have fallen and each time they have modified their plan slightly to make them stay. Once stable, Ji counts the blocks and Javier turns to the teacher and proudly says, “Look at our 5-story building, you should shop here.”

|

|

Reflection Can you find development and learning for Javier and Ji in each of the categories listed in the Vignette?

|

Play: The Vehicle for Development and Learning

Children are born observers and are active participants in their own learning and understanding of the world around them from the very beginning of their existence. This means they are not just recipients of a teacher’s knowledge. Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) challenges early childhood professionals to be intentional in their interactions and environments to create optimal experiences to maximize children’s growth and development. Under this umbrella of DAP, knowledge is based upon discovery and discovery occurs through active learning and abundant opportunities for exploration. Through a “hands-on” approach and using play as a vehicle, children will develop the skills necessary for growth and development and maximize their learning.

Teachers play a pivotal role in children’s active construction of knowledge. They intentionally provide the environments, interactions, and experiences that support children in actively building concepts, skills, and overall development. The role of the teacher who works with young children in early childhood is to support children’s active construction of knowledge.

Early childhood teachers are responsible for:

- Offering children well-stocked play spaces where they can construct concepts and ideas, preferably in the company of peers

- Designing daily routines that invite children to be active participants and to use emerging skills and concepts

- Supporting children’s learning through interactions and conversations that prompt using language and ideas in new ways

Types of Play

When we think about play, it is important to remember that there are different types of play that children engage in. Quality teachers incorporate plans for each of these types of play throughout the day. They set up activities and plan experiences that will allow children to make sense of their world through each of these play modalities. A common framework used by teachers as they define areas and activities is as follows:

- Socio-Dramatic Play: Acting out experiences and taking on roles with which they are familiar. Often incorporates Symbolic Play where children use materials and actions to represent something else.

- Creative Play: Trying out new ideas and using imagination, with a focus on the process rather than the product.

- Exploratory Play: Using senses to explore and discover the properties and function of things.

- Constructive Play: Using materials to build, construct, and create.

- Loco-motor Play: Moving for movement’s sake, just because it is fun.

Think about the concepts that are being developed by each of the types of play. Is it developing the “whole child”?

Stages of Play Development

Play is all about having fun! Any activity organized or unstructured, the child finds fun and enjoyable is considered play. But play is much more than just a fun activity for your child! As a child grows, they go through different stages of play development.

Children who use their imagination and ‘play pretend’ in safe environments are able to learn about their emotions, what interests them, and how to adapt to situations. When children play with each other, they are given the opportunity to learn how to interact with others and behave in various social situations.

Be sure to give your child plenty of time and space to play. There are 6 stages of play during early childhood, all of which are important for the child’s development. All of the stages of play involve exploring, being creative, and having fun. This list explains how children’s play changes by age as they grow and develop social skills.

The 6 Stages of Play

Unoccupied Play – 0-3 months

- When baby is making movements with their arms, legs, hands, feet, etc. They are learning about and discovering how their body moves.

Solitary Play – 0-2 years

- When a child play alone and are not interested in playing with others quite yet.

Spectator/Onlooker Behavior – 2 years

- When a child watches and observes other children playing but will not play with them.

Parallel Play – 2+ years

- When a child plays alongside or near to others but does not play with them.

Associate Play – 3-4 years

- When a child starts to interact with others during play, but there is not much cooperation required. For example, kids playing on the playground but doing different things.

Cooperative Play – 4+ years

- When a child plays with others and has interest in both the activity and other children involved in playing.

What Children Learn Through Play

Just like the “whole child” is often broken down into developmental domains for studying, so too is learning. Many aspects of learning occur simultaneously; it is integrated and connected. To define learning we often break it into categories. Because the connection between play and learning is so important, the way it is broken down exists in many forms, including assessments, planning resources, and the frameworks and foundations mentioned above. Below is a compilation of such skills, compiled by Eyrich (2016) tying development into learning through play.

What Children Learn Through Play

|

Domain |

How it connects to learning |

|

Physical |

|

|

Cognitive |

|

|

Language |

|

|

Social |

|

|

Emotional |

|

|

Creative |

|

Why Play?

As children learn through play and inquiry, they develop many of the skills and competencies that they will need in order to thrive in the future, including the ability:

- To engage in innovative and complex problem-solving and critical and creative thinking

- To work collaboratively with others

- To take what is learned and apply it in new situations in a constantly changing world (The Kindergarten Program, 2016, p.11)

The benefits of play are recognized by the scientific community. There is now evidence that neural pathways in children’s brains are influenced by and advanced in their development through the exploration, thinking skills, problem-solving, and language expression that occur during play.

Research also demonstrates that play-based learning leads to greater social, emotional, and academic success. Based on such evidence, ministers of education endorse a sustainable pedagogy for the future that does not separate play from learning but brings them together to promote creativity in future generations. In fact, play is considered so essential to healthy development that the United Nations has recognized it as a specific right for all children.

Educators should intentionally plan and create challenging, dynamic, play-based learning opportunities. Intentional teaching is the opposite of teaching by rote or continuing with traditions simply because things have always been done that way. Intentional teaching involves educators’ being deliberate and purposeful in creating play-based learning environments. When children are playing, children are learning.

Benefits of play:

- Inspires imagination

- Facilitates creativity

- Fosters problem solving

- Promotes the development of new skills

- Build confidence and higher levels of self-esteem

- Allows free exploration of the environment

- Fosters learning through hands-on and sensory exploration

It is now understood that moments often discounted as “just play” or as “fooling around” are moments in which children are actively learning (Hirsh-Pasek et al. 2009; Jones and Reynolds 2011; Zigler, Singer, and Bishop-Josef 2004; Elkind 2007.) While engaged in play, children explore the physical properties of materials and the possibilities for action, transformation, or representation. Children try out a variety of ways to act on objects and materials and, in so doing, experiment with and build concepts and ideas. This active engagement with the world of people and objects starts from the moment of birth.

This description of the young child as an active participant in learning informs the role of the teacher who works with young children from birth to five. Early childhood teaching and learning begins with teachers watching and listening to discover how infants and young children actively engage in making sense of their everyday encounters with people and objects. When teachers observe and listen with care, infants and young children reveal clues about their thinking, their feelings, or their intentions. Children’s actions, gestures, and words illuminate what they are trying to figure out and how they attempt to make sense of the attributes, actions, and responses of people and objects. Effective early childhood teaching requires teachers to recognize how infants and young children actively search for meaning, making sense of ideas and feelings.

When teaching is viewed in this light, children become active participants alongside teachers in negotiating the course of the curriculum. Families who entrust their children to the care and guidance of early childhood teachers also become active participants in this process. Shared participation by everyone in the work of creating lively encounters with learning allows a dynamic exchange of information and ideas—from child to adult, from adult to child, from adult to adult, and from child to child. The perspective of each (child, family, teacher) informs the other, and each learns from the other. Each relationship (child with family, child with teacher, child with child, and family with teacher) is reciprocal, with each participant giving and receiving from the other, and each adding to the other’s learning and understanding.

Interactions

It cannot be repeated enough that human beings are social creatures that thrive on relationships. In order to maximize a child’s interests, willingness to take risks, try again when initial attempts have not gone as planned, and learn to their fullest, we must establish and maintain relationships with children that foster trust and encourage autonomy and initiative. Interactions should be as much of what we plan for as the materials and experiences themselves. Built into every curriculum plan should be thoughts about how the teacher will:

- Create a sense of safety and trust

- Acknowledge children’s autonomy

- Foster a growth mindset

- Extend learning through open-ended statements and conversations

The importance of establishing and maintaining relationships to foster brain development. The concept of a “Neuro-Relational approach” will be present in the curriculum that we plan for young children.

Quality interactions will include:

- Valuing each child for who they are

- Finding something special and positive about each child

- Maintaining a positive attitude

- Finding time each day to interact and make a connection with every child

- Respecting children’s opinions and ideas

- Being present for children

- Reflecting back what they say and do

- Listening to listen hear rather than respond

- Creating a warm and welcoming environment

- Being consistent as a means of establishing trust

- Focusing on the process

- Focusing on what children CAN do rather than what they can’t do YET

- Including families as valuable team members

- Understanding and respecting each child’s individual and group culture

Communication goes hand in hand with interaction. Being aware of what we are saying and how we are saying it is crucial in establishing and maintaining relationships. Positive communication includes:

Nonverbal:

- Get down to children’s level

- Observe

- Be present

- Listen

- Understand

- Use positive facial expressions

- Look interested

- Smile

Verbal:

- Be aware of the tone and volume of your voice

- Speak slowly and clearly

- Use facial expressions and body movements that match your words

- Give choices and share control

- Focus on the positive

- Describe what you are doing as children are watching

- Model appropriate language

- Reflect back what children are saying

- Have conversations with multiple exchanges

- Consider close vs. open-ended questions and statements

The type of questions you ask will elicit different responses. Sometimes we want a direct answer while most of the time we want to generate deeper thinking to promote learning. Consider each of the questions below regarding the color blue:

- “Are you wearing blue today”?

- “What color are your pants”?

- “Tell me all the things you see that are blue”

Considering what type of thinking we want to promote enables us to create questions and statements that spark that knowledge. Thinking is often broken down into two types:

- Convergent thinking – emphasizes coming up with one correct response: “converging” on the “right” answer.

- Divergent thinking – emphasized generating multiple responses, brainstorming and “thinking outside the box”: “diverging” into different ways of thinking and answering.

Both can be valuable as children develop and learn. Often starting with divergent questions and then following up with convergent questions allows for broad thinking that can then be narrowed down.

Plan-Do-Review

Often referred to as the Plan – Do (implement) – Review (evaluate) cycle, this type of approach allows us to continuously provide the most effective curriculum to the young children in our care.

Plan

As with most endeavors, we are more effective when we plan curriculum ahead of time. This helps us to be prepared and to adjust our ideas to be flexible as the children engage with what we have planned.

Reasons to plan:

- Make sure our plans meet the needs, interests, and abilities of the children

- Make sure we understand the learning and development that will occur

- Make sure we have all the materials we will need

- Make sure we know where in the environment to set up

- Make sure we know how to set up

- Make sure we know how to encourage children to participate

- Make sure we have thought through behavioral issues that might arise and how to manage them

- Make sure we have thought through the interactions that will take place

- Make sure we know how we will encourage the children to clean up

- Make sure we know how we might gather observational notes

- Make sure we have thought through how we might document and share this experience with parents or others.

If we have planned thoroughly and thoughtfully, it allows us to implement our plans and to reflect on them afterward, using that information for future planning.

Most programs are broken down into segments of the day, beginning with the arrival of the children and ending with their departure. Teachers will plan for all segments of the day, both inside and outside, which might include:

- Arrival and Departure

- Small group time

- Large group time

- Centers

- Child initiated play

- Nutrition (snack, lunch,…)

- Self-help (washing hands, toileting, napping,…)

- Transitions between all segments of the day

- Others as each program dictates

When planning it can be helpful to know that certain terms are used in a variety of ways by various programs. Because this chapter is written for a diverse group of future early childhood educators, we will use these terms interchangeably so that you are ready for the vocabulary used wherever you may work.

Some of the terms most frequently used to represent the “goings-on” you will plan for are:

- Lesson

- Activity

- Learning Experience

- Curriculum

- Teaching Moment

While they may have slightly different “official” meanings, they overlap in our field and can all be found to begin with a plan based on children’s interests and needs, implemented according to the plan (with modifications as they occur), and reviewed/evaluated afterward through reflection to assess and build upon for the future.

Below are examples of generic planning forms. You will see planning for a specific activity and planning for the entire day. For each there will is a blank version and a sample version. The programs you work in will each have their own unique method and planning forms, but most will include some, if not all, of the information included here.

Planning Template for an Activity

Below is a template for a specific activity. It contains all the elements you need to consider when planning an activity for a classroom of children.

Lesson Plan Template

ECE 1011 Introduction to Early Childhood Education

|

Title of Activity |

Content Areas |

Age Group |

|

Learning Objectives: (After completing the activity, the children will know….)

|

||

|

What Colorado Curriculum Standards does this activity meet?

|

||

|

Specific skills children use when doing this activity:

|

||

|

Materials/Supplied needed:

|

||

|

What teaching techniques or instructional strategies will you use with the activity |

|

|

|

Introduction/Motivation: How will you get the children’s attention to engage them in learning?

|

||

|

Procedures: Steps to implement the planned activity

|

||

|

Questions I will ask during the activity that will promote higher level thinking:

|

||

|

Closure – Check for understanding; How will you know what the children learned? How will you know they learned the objective?

|

||

|

Differentiation: Provide at least one example of how you will differentiate this activity for children who need additional support

|

||

|

Additional notes: |

||

Planning for a Thematic Unit of Study

When planning for a unit of study, you will create a web of various activities and learning experiences in all curriculum areas – math, science, literacy, cooking, art, large and fine motor skills, etc. Follow the process below and compare it to the model created by a student from Pikes Peak State College.

Think about the big ideas or concepts that you want young learners to explore through study using a variety of learning activities. Write down four or more big ideas or concepts on your planning web.

Brainstorm ways children can have real experiences with the topic and activities through which they can express what they know–through art, building blocks, dramatic play, creating books, etc.

Add to your web activities like specific songs, fingerplays, storybooks to read together, and real experiences (field trips or class visitors) for each of your big idea concepts. Each big idea should have 4-6 activities listed.

Review the Colorado Academic Standards for Preschool. Pick 2-3 standards that your curriculum web will address. Add these early learning standards to your planning web. See attached standards

Write down on your planning web how you will assess the children to know if they met the selected early learning standard(s). Will you use a checklist, anecdotal observation, photos with notes, work samples from the children, or another method? (CCCS RtT)

Planning a Daily Schedule

|

Daily Lesson Plan |

|||||

|

Date |

Class |

||||

|

Time |

Activity |

Materials |

Purpose |

Interaction |

Other |

|

Arrival 9:00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Circle Time 9:10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Learning Centers 9:20-10:30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clean Up 10:20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Snack 10:40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Outside 10:55-11:40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Circle 11:40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Departure 12:00 |

|

|

|

|

|

Do

There are many resource websites and books with ideas to spark your initial planning. The best way to consider what to plan comes from the children. Always consider WHO you are planning for and WHY you are planning. The rest will follow. Here are some general considerations for planning to follow:

Consider both the group and individual children; be inclusive of all

- Know their interests

- Know their ability levels

- Focus on what they CAN do; start with where they are

- Understand your resources (time, materials, location,…)

- Understand development of the ages and stages you are planning for

- Plan for the “whole” child

- Know your goals and objectives

- Integrate curriculum and plan for all types of play

- Consider the families, communities and cultures represented

- Include others in the planning process when possible (colleagues, families, children)

- Plan ahead of time how to transition to the next segment of the day

- Jot down quick notes to refer to later when you reflect

- Don’t worry if it doesn’t go exactly as you planned, that’s expected

- Enjoy yourself and the children, remember “this is the fun part”

Another consideration will be how you will implement the activities you plan. There are several different teaching methods to think about and most teachers will balance various strategies throughout the day:

- Child Directed – child introduces and directs activity

- Child Demonstrated – child demonstrates while teacher observes

- Assist – child explores and teacher provides minimal assistance

- Scaffold – child attempts and teacher provides guided support as needed

- Co-Construct – child and teacher or child and child work collaboratively

- Teacher Demonstrated – teacher demonstrates while child observes

- Teacher Directed – teacher introduces and directs activity

Review

The third part of the Plan-Do-Review cycle involves reflecting on what was planned and implemented. Curriculum planning is one of the primary duties teachers engage in, and as such requires a great deal of reflection and review. Some of this will be done informally as you go about your day. Other times it may be helpful to reflect more formally, in order to capture strengths and areas of growth, both in yourself, the children, and the curriculum that you are planning for them. As a form of “assessment,” this feedback proves extremely valuable for teachers and programs. Below are examples of two types of forms teachers might use in their reviews.

|

Curriculum Implementation Evaluation / Reflection A. Overall impression / comments about your activity (Be specific): B. What went well? C. What did not? D. What type of interactions took place during the implementation of your activity? (child – child, child – adult, …) E. How did individual children respond to your implementation? Did they respond the way you anticipated? (Please be specific and use examples whenever possible) F. If you were to implement this activity again, how would you modify it? Think about:

|

|

Daily Curriculum Reflection

|

Some programs will set up areas of the indoor and outdoor classroom with a variety of materials for children to choose from. Others will set up stations for children to participate in. Some portions of the day will include individual, small, and large group experiences. All should be carefully planned with intention and meaning for the children that will be engaging in them.

Play vs. Structure

Giving children the freedom to direct their own play is an idea that goes all the back to the philosophy Jean-Jacque Rousseau (1712-1778). Over the next 300 years, this belief fell in and out of favor.

The term “free play” was introduced early in the 20th century. Patty Smith Hall (1868-1946) defined “free play” as follows: “In free play, the self makes its own choices, selections, and decisions, and thus absolute freedom is given to the play of the child’s images and volition in expressing them” (Shipley, 2012, p.59-60)

In the 1960s and 1970s, any structure in programs for young children was frowned upon. (Shipley, 2012, p. 59). The pendulum swung back slightly during the 1980s when educators such as David Weikart (1931-2003) advocated that some structure was appropriate to enhance the benefits of play.

The early 1990s ushered in a new emphasis on the importance of the development of children’s self-esteem as a curriculum goal. Children were seldom held back in school for not achieving academic goals. Pedagogical practice was praising children for their efforts, not the result. This approach was labelled “child-centered education.” Unfortunately, it became incorrectly interpreted as having lower expectations for children. This misinterpretation resulted in the “back to basics” movement that was based on an unsupported linkage between poor results on standardized tests and child-centered education.

In the late 1990s, the Reggio Emilia Approach gained prominence as a successful child-centered, constructivist, curriculum model. This approach balances “both sides of the play versus structure issue, an influence that restored the credibility of developmental skills as viable outcomes and play-based intervention to help children achieve them.” (Shipley, 2012, p.60)

Increasing globalization in the 2000s has renewed the interest of parents in early academic success for their children. It is common for parents to ask Early Childhood Educators “Why do you let the children play all day?” Early Childhood Educators must:

- Be knowledgeable about the value of play

- Be able to clearly explain the developmental outcomes that children are achieving through play

- be able to make learning visible through documentation.

“Learning success for the information age emphasizes the ability to perform complex tasks and roles.” (Shipley, 2012, p.63). 21st century skills that are developed during play include:

- Making choices

- Staying focused for extended periods of time

- Demonstrating understanding

- Social skills such as entering a group, negotiating roles, collaborating with others

- Using divergent thinking skills to solve problems

- Assessing risk

The Diversity of Beliefs about Play

When children (or adults) introduce playfulness into what has been initiated as activities other than play, they in fact, at least temporarily, reframes the activity as play(ful). Research has shown that parents differ in their view of the merits of play (Roopnarine, 2011). Parents from what is referred to as European or European- heritage cultures, and particularly among higher-educated middle-class backgrounds, differ in being positive to “‘concerted cultivation’ during socialization (constantly coaching, creating opportunities) compared to low-income families who believe that children naturally acquire certain skills,” including play support. Regarding the latter, there was a positive relationship between play support and parental education, and an inverse relationship between parental education and academic focus, suggesting that parents with higher levels of educational attainment were more likely to endorse play as a means for learning early cognitive and social skills than those with lower levels of educational attainment.

Not surprisingly, but importantly, variation in parental beliefs concerning the value of play corresponds with the frequency, nature, and quality of parent-child play, with parents in European and European-heritage communities engaging, for example, in playful activities with children and objects in ways that involve labeling more than parents with other cultural backgrounds.

Unfortunately, the lay view that play is not serious, and thus not important to ‘real’ education, is still all too common. In their extensive review of studies on play in education, Fisher, Hirsch-Pasek, Golinkoff, Singer, and Berk deduce this controversy to a more long-standing debate on how children learn. They argue that historically there are two traditions to this question, what they refer to as “the ‘empty vessel’ approach” and “the whole-child perspective” respectively.

The Empty Vessel Approach

The Empty Vessel Approach comes from behaviorist ideas and suggests that children need to learn a core set of basic skills. According to this view, the best way to teach is through a carefully planned and scripted method. Teachers are seen as the main source of information, telling students the important facts they need to know for academic success. Learning is broken down into specific subjects, like math, reading, and language, to make sure the right knowledge is taught. This approach often involves worksheets, memorization, and assessments, and doesn’t place much value on play, even in preschool.

The Whole Child Approach

The Whole Child Approach, unlike the empty vessel approach, sees children as active participants in their learning. In this approach, it’s important for learning to be meaningful, and play is seen as a key way for children to learn new things, practice skills, and take part in activities that help them grow. A key idea in this approach is “agency,” which means giving children the power to take charge of their own learning. In general, the field of early childhood education is most closely aligned with the whole-child approach. However, it is important to remember that making an “either/or” distinction between the two approaches is an oversimplification and one would not expect to find clear-cut examples of either approach.

Reviewing studies on play and learning, Fisher et al. conclude that “the findings show that play can be gently scaffolded by a teacher/adult to promote curricular goals while still maintaining critical aspects of play.” What they refer to as ‘playful learning’ consists of two parts: free play and guided play. The latter has two aspects: adults enriching children’s environment with toys and other objects relevant to a curricular domain (e.g., literacy), and adults playing along with children, including critically, asking questions and “the teacher may model ways to expand the child’s repertoire (e.g., make sounds, talk to other animals, use it to ‘pull’ a wagon).” While children’s play provides the basis for this form of pedagogy, “teacher guidance will be essential.” Teacher guidance, as Fisher et al. point out, “falls on a continuum,” that is, the question is not whether or not the teacher participates (or should participate) but the extent to – and more critically, how.

The example of developing preschool children’s shape concepts can illustrate the merits of this form of pedagogy. In the study, children were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: guided play, direct instruction, or control condition. In the guided play condition, children were encouraged to “discover the ‘secret of the shapes’” and adults asked what the researchers refer to as ‘leading questions,’ such as how many sides there are to a shape. In the instruction condition, in contrast, the adult verbally described the shape properties to the children. In the control, condition children listened to a story instead of engaging with shapes. Afterward, the children were asked to draw and sort shapes.

Results from a shape-sorting task revealed that guided play and direct instruction appear equal in learning outcomes for simple, familiar shapes (e.g., circles). However, children in the guided play condition showed significantly superior geometric knowledge for the novel, highly complex shape (pentagon) than the other conditions. For the complex shapes, the direct instruction and control conditions performed similarly. The findings suggest discovery through engagement and teacher commentary (dialogic inquiry) are key elements that foster and shape learning in guided play.

This research concluded there is no difference in learning outcomes between guided play and direct instruction when it comes to relatively simple content, but when it comes to more complex content, guided play outperforms direct instruction; in fact, as found, when it comes to complex content, direct instruction was no better than what the control group performed (i.e., in this case, direct instruction made no difference to learning outcomes, on a group level). As clarified by Fisher et al.’s reasoning, teacher participation is critical to the success of guided play, not least to engage children in talking about the matters at hand and how these may be understood.

Learning Through Guided Play

Direct instruction gets educational content across quickly and may be effective for certain areas of learning. However, children are primarily passive during direct instruction, and studies show that children learn best when they’re active and engaged. Therefore, real learning happens through play.

Guided play is purposeful as the teacher intentionally sets up activities with learning goals and guides the child to achieve them. Learning goals can include social, cognitive, literacy, and early math skills.

What is guided play?

Guided play is when an adult gets involved in a child’s play activities to help them learn new skills. It’s a form of play-based learning that falls between free play and direct instruction as it combines child autonomy and adult guidance. While children thrive with free play, which is voluntary, flexible, and fun, sometimes teacher support is necessary to reach specific learning goals. Guided play is also fun and engaging, but unlike free play, it focuses on a specific learning objective. With guided play, the teacher can design a setting focused on a specific learning goal and have the children explore and discover within that context. Alternatively, the teacher will watch the children play, make comments, ask questions, and encourage children to ask questions too.

Guided play vs free play

At a glance, guided play looks similar to free play, so it might be difficult to tell them apart by simply watching the children’s activities. To tell them apart, it’s essential to look at the teacher’s role, which is more active in guided play than free play.

In guided play, the teacher intentionally plans the learning setting with specific learning goals. For example, to help children learn shapes or colors, the teacher may use building blocks in specific shapes or colors to help reinforce the concept. There are no specific learning goals for free play, so the teacher may use blocks just for the child’s sake of building a structure.

During guided play, the teacher will observe the child’s play and must ask open-ended questions to extend their learning. For example, “What shape is that?” or “What color is that?” or “What do you think will happen if you put it at the top?” During free play, the teacher should observe the child’s activity and can ask questions too. However, they may not interact with the child unless necessary, for example, if the child asks a question or seems frustrated with the activity.

During free play and guided play, the teacher can document their findings about the child’s learning by taking photographs, videos, and asking children to talk about the activity. While documentation is a “nice-to-have” for free play, guided play needs evidence of a child mastering a skill or achieving a goal.

Benefits of Guided Play

Research indicates that guided play is a powerful vehicle for early learning. Here are some benefits of guided play:

- Builds active listening skills

- Develops a love for learning

- Builds problem-solving and critical thinking skills

- Builds Cognitive Skills

- Builds communication and social skills

As a teacher you can guide play by creating and environment based on a learning goal. Here are examples of guided play activities:

- Molding playdough into different letters or numbers

- Sticking numbers on a magnetic board in order from one to ten

- Playing with foam or wooden shapes

- Memory tray games (let children choose the objects for the tray)

- Nature walks outside

- Simple jigsaw puzzles

- Activities that combine music and movement

- Pretend play such as restaurant, hair salon, or doctor’s visit

- Sensory play activities that stimulate children’s senses of touch, taste, smell, sight, hearing, body awareness, and balance

Guided play is play with a purpose. It can support individual needs and help develop critical skills and achieve specific learning goals in a hands-on setting.

The Behavioral Side of Curriculum

Rather than thinking of children’s behavior as occurring separately from everything else that goes on in the classroom, it can be helpful to recognize that it is a part of everything else. As we plan interactions and experiences that are meaningful, we consider a variety of factors that affect behavior. Part of every plan should be an understanding of who children are and intentionally planning for them. Just as with other skills that children are learning, they are learning to control their bodies, use their words, self-regulate, wait their turn, be patient, and a host of other social and emotional skills they will help them be able to manage themselves in social situations. Learning these life skills is no different from any other concept they will learn by exploring, repeated exposure, and having it make sense to them. As will other concepts, they need teachers who develop relationships with them, focus on what they CAN do, and maintain a positive attitude.

There is no magic approach to helping children learn to manage their behavior and no secret book with all of the answers. Instead, there are a variety of factors to consider and approaches to try to guide behaviors in the ways we prefer. Here is a summary of considerations as we plan for the children in early childhood education programs.

As early childhood professionals, we have an ethical obligation to understand how behavior is affected by the following factors and to plan accordingly. Understanding why a child might be behaving in a certain way can assist in planning appropriately:

The “whys” of children’s behavior teachers should consider

- Development – what to expect at various ages and stage for the “whole” child

- Environment – the physical space, routine, and interpersonal tone

- Family and Cultural Influences – influences and variations in expectations

- Temperament – individual personality styles, approaches, and ways of interpreting events

- Motivation – purpose (communicating, relating, attention, control, revenge, inadequacy, fear of failure,…)

Once we understand the “whys” of behavior, we can plan interactions that foster the behavior we desire. Here are some highlighted interactive strategies to consider.

Useful teacher interactions when planning for children’s behavior (in addition to the interactive considerations posed earlier):

- Consistency

- Clarity

- Realistic limits and expectations

- Calmness

- Focus on the behavior, not the child

- Focus on what the child can do and is doing appropriately

- Positive direction (for example instead of “don’t run” say “use walking feet”)

- Reflection and logic rather than immediate response and emotion

Some strategies to try include:

- Ignore – Can be effective if a behavior is annoying rather than dangerous. “If you choose to continue using a whining voice I will choose not to listen. As soon as you use your talking voice, I would like to hear what you have to say”

- Redirect – Directing the child to a more positive way of using that behavior. “Inside we use our walking feet, when you go outside you can run” or “We don’t throw things at other people, if you would like to throw let’s find the target and beanbags”

- Active Listening to understand – Validating what the child is saying. “I hear you saying that you want a turn, you sound very sad” or “you worked very hard on that block structure, and you are angry it got knocked over”

- Give Choices – State what needs to be done and then give 2 options for how it can be done. “It’s time to clean up now, will you clean up the paintbrushes or the paints first?” or “It’s time to come inside now, do you want to come in like a mouse or a dinosaur?”

- Logical Consequences – As children behave in certain ways (both “positively” and “negatively”) consequences will logically happen. “If you talk to your friends in that tone, they may continue not to want to play with you. If you want to play with them, what can you do differently?” or “We are having snack now; if you choose not to eat you will probably be very hungry by lunchtime”

- Problem Solving/Conflict Resolution – Helping children to solve their own issues with support as needed. “What can you do about that?” or “How might you solve that problem” or “it sounds like you both want to play with the same toy, I wonder how you will work that out?”

- Short removal with reflection and return – Taking a moment to leave a situation to gain composure and return more successfully. “It is hard for you to keep the sand in the sandbox right now. I’m going to ask you to leave the sandbox for a few moments and think about how you can be respectful to the others that are sharing this space with you. Where will you go to think?”) A very brief time later) “what can you do differently next time you enter the sandbox? Great, would you like to try out your solution? Come on back and show me.” “You did it!”

Partnerships with Families

In addition to strengthening relationships with children, sharing observations with children’s families strengthens the home–program connection. Families must be provided opportunities to increase their child observation skills and to share assessments with staff that will help plan the learning experiences.

Families are with their child in all kinds of places and doing all sorts of activities. Their view of their child is even bigger than the teacher’s. How can families and teachers share their observations, their assessment information, with each other? They can share through brief informal conversations, at drop-off or pickup time, or when parents volunteer or visit the classroom. families and teachers also share their observations during longer and more formal times. Home visits and conferences are

opportunities to chat a little longer and spend time talking about what the child is learning, what happens at home as well as what happens at school, how much progress the child is making to problem solve if the child is struggling and figure out the best ways to support the child’s continued learning.

Final Thoughts

As can be seen, there is much to consider when planning, implementing, and evaluating curriculum for early childhood programs. At the core of quality curriculum is the notion of Developmentally Appropriate Practices, including observing and understanding the individual children in your care, developing, and maintaining positive relationships and interactions, effectively communicating, valuing the role of play in learning, and understanding that children’s behavior is a part of the learning process.