Childhood Behaviors and Guidance Strategies

|

Topical Outline |

Colorado Standard Competencies |

|

Guidance Strategies

|

Identify appropriate guidance techniques and classroom management strategies. Defining developmentally appropriate practices for programs serving young children |

Vocabulary Standard Competency: Explain basic early childhood and early childhood special education terminology |

|

Behavior: Behaviors are the way in which a child acts, especially toward others. Behavior can be positive, supporting learning, positive relationships and interactions with others or be challenging and interfere with the same. Challenging Behavior: Challenging behavior is inappropriate behavior that children use and rely on to get their needs met. These behaviors interfere with learning, development, and success at play. Challenging behaviors may include aggressive and disruptive behavior, or timid and withdrawn behavior. Communication: Communication is the ability to understand and to be understood, and is essential to relationships, learning, play, and social interaction. Communication can be verbal or non-verbal Compliance: The child’s ability or willingness to conform to the direction of others and follow rules. Cultural Dissonance: Cultural dissonance is defined as a sense of disagreement, tension, confusion, or conflict experienced within a cultural environment. Emotional Development: Emotional development refers to the child’s development of and identification of emotions and feelings, and includes the child’s experience, expression, and management of their emotions. Goal: A goal is the final product you are working toward Guidance: Child guidance means to teach and to help children learn social skills that will support them to have a good relationship with other people. Interaction: The way in which the child initiates social responses to parents, other adults, and peers Planned Ignoring: Deliberate and intentional inattention to an identified attention-seeking or other strategic behavior. Reflective Practice: The ability to reflect on one’s actions to engage in a process of continuous learning Relationships: Relationships are the construct in which children and teachers talk, share experiences, and participate in activities that support the child to be engaged in learning. Relationships support a child to think, understand, communicate, express their emotions, and develop social skills Self-regulation: Self-regulation is a child’s ability to understand and manage their behavior. This process supports a child to manage their reactions to feelings and help to regulate their emotions Strengths-Based Approach: Interactions that begin with helpful and encouraging mindsets, that support adults to see children and families in a more optimistic manner and allows us a strong foundation to build our positive relationship. Using a strengths-based approach begins with focus on a child’s (and family’s) strengths Unwanted (undesired) behavior: Behavior(s) that challenge us as adults, therefore are “unwanted.” These behaviors are typically seen as negative |

Introduction

This chapter provides insight into child behavior is within a developmentally appropriate context. Later in the chapter we will address intentional and positive guidance to teach children appropriate and expected behaviors. The content of this chapter is presented in a positive or strengths-based approach to support children as they grow, develop, and learn. This approach centers on our lens looking for and identifying a child’s strengths as a starting point for our work.

The foundation begins with building a shared definition of what guidance is, as well as what it is not. Throughout the chapter you will examine the basis of behaviors both seen and unseen. It is also important to delve into some background and information about neurodiversity and trauma, and how this relates to and impacts behavior. The chapter will also address how emotions, psychological state, and social relationships influence child behavior. The final focus area is communication with families along with mutual perspectives in guidance and the role of reflective practice.

Behavior Defined

According to the dictionary published by Merriam-Webster, behavior is a noun, and used to describe the way in which someone conducts oneself or behaves. It is important to note that behavior includes not only the way in which one acts or conducts oneself, but especially how one acts or interacts toward others. Likewise, behavior is the way a person acts in response to a particular situation. Behavior has two purposes:

- to get something or

- to avoid something

Children learn all behavior. They learn from watching others and we learn from the reactions we get in response to behavior. As behavior is learned, it can also be unlearned. When we stop and ask the question “why is this behavior occurring?” we can identify the opportunity to teach new, more appropriate behaviors as replacement.

All behavior is communication. This communication happens every moment of every day. This important function is a signal that a child may not have the words or skills to tell you what they need, so they communicate with behavior. It can also be that a child does not even know what they need! When we understand and acknowledge this communication that is the basis of unwanted behavior or “misbehavior,” we can work to change that communication into a form that is socially acceptable, safe, and healthy.

Behavior is observable. It is what we see and what we can hear, such as a child throwing a block, standing up, speaking, whispering, yelling, or arguing with a classmate. On the reverse side, behavior is how a feeling is expressed, not what the child is feeling. An example of expressing a feeling is that a child may show anger by making rolling her eyes, making a face, yelling, or crossing his arms, or turning away from the adult. These are observable actions and are more descriptive than just stating that the child looks anxious.

Behavior is measurable. This means that the early care and education professional can define and describe the behavior in objective, concrete, fact-based terms. The adult can easily identify the behavior when it occurs, including when the behavior begins, ends, and how often it occurs. An example of this is taken from circle time and the child who is “interrupting all the time.” This behavior is not measurable because it is not specific. However, stating that “Holly yells, ‘teacher!’ 4 times during circle time” is specific and we can measure and track the data each day at circle time. Using this operational definition of objective data, anyone observing in the classroom would be able to identify specifically which behavior the teacher is working to change.

Behavior does not occur in isolation. The process of behavior has three parts:

1. The action or event that comes first (the trigger)

2. The resulting behavior(s)

3. The consequences of or reaction to the behavior.

Behaviors are visible. This visibility is in terms of desired and undesired behaviors. Think for a moment in terms of behavior being like an iceberg. Above the water we see and observe the behavior. What we do not see is the part of the iceberg that is below the water. It is the same with behavior. We see the actions and manifestations of the behavior. We do not see the underlying characteristics of feelings, thinking and attitude(s).

Behavior falls under the domain of social and emotional development. Children are born with the desire and need to connect with those around them. When parents and teachers along with other caregivers create positive relationships with children beginning at birth through the early years, they value their diverse cultures and languages, children feel safe and secure. This creates a base for strong social and emotional development. This also affects how children experience the world, express themselves, manage their emotions, and establish positive relationships with others.

Consider this image of an iceberg. Above the water represents what is seen-observable behavior. Below the water represents what is unseen – unobservable behavior.

Behaviors are an outcome (or result) that can be observed. Above the ground the behaviors we see children say and do might include indicators adapted from Mona Delahooke’s work:

| Positive Behavior | Not-so-Nice Behavior |

|

|

A child’s behavior may not be communicating what it seems outwardly. Every behavior has a motivation or purpose. While we cannot assume that we know the motivation for the behavior, we can observe the results of the motivations. Those observations must be objective, factual, and descriptive to assist in identification of the motivation. Any of these motivations can be the reason for behavior:

| I feel angry.

I feel frustrated. I feel scared. I feel happy. I feel loved. I feel proud. I feel lonely. I feel worried. |

I feel embarrassed.

I feel sad. I feel sick. I am tired. I am hungry. I do not feel safe. I do not belong. I am not respected. |

I am not understood.

I am not accepted. I do not matter. I do not feel loved. I cannot do things by myself. |

Look again at the photo of the iceberg. Most of the ice is underwater, therefore not observed. Here are some behaviors that are typically “under the surface” and are not seen are:

- social skills

- basic needs

- physical safety

- need to belong

- security

- hunger

- thoughts

- executive functioning

- environmental stressors

- attention

- sleep

- attachment

- need for connection

- need for attention

Here are some needs that are an underlying cause of behavior in children: (dfwchild.com)

- Sensory needs

- Emotions

- Self-esteem

- Developmental level

- Fear

- Anger

- Power

- Sadness

The theory behind the iceberg model of childhood behavior is that there are many things that influence the way that children act and react, including the skills, knowledge, experience, social role or values, self-image, traits, and motives. Under the surface in the iceberg are the unseen forces that can shape their behaviors.

As adults, we need to take the time to understand behavior and the motivations or causes of behavior. True behavior “problems” or challenges are those that are continuous and that get in the child’s way of social relationships, communication, and learning. These misunderstood behaviors can potentially cause harm to the child, the family, other children, and other adults.

|

|

Reflection Behaviors are communication and are both seen and unseen. Think in terms of the iceberg presented above. The ice is seen, just like in behavior where we can observe changes and growth. The photo shows that the ice below water, hidden, and not easy to see or observe. That ice, even though not observable, is a vital part of the whole.

|

The Role of Relationships – How Relationships, Social-Emotional Development, and Behavior(s) Connect

Now that we have a shared understanding of how behavior is defined, this section of the chapter will support you to explore and reflect on the connection between relationships, social development, emotional development, and behavior. Did you know that relationships with others may influence behavior either positively or negatively?

Reflect for a moment on this photo of the young boy playing Jenga. As he moves and/or removes the blocks the structure becomes unbalanced and even unpredictable. A child’s behavior and the relationships in his or her life can mirror this game of Jenga. Social and emotional development are also important to the foundation as they help to inform how the child manages feelings and emotions and how he/she can socialize and cooperate with others within a relationship.

According to the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, young children experience their world as an environment of relationships, and these relationships affect every aspect of their development. Simply put, relationships are the “active ingredients” of the environment’s influence on healthy human development. They incorporate the qualities that best promote competence and well-being – individualized responsiveness, mutual action-and-interaction, and an emotional connection to another human being such as a parent, peer, grandparent, aunt, uncle, neighbor, teacher, coach, or any other person who has an important impact on the child’s early development. Relationships engage children in the human community in ways that help them define who they are, what they can become, and how and why they are important to other people (NSCDC, 2004).

When children have secure and stable relationships with caring adults, they are more able to develop warm and positive relationships with others. These children are more excited about learning, more positive about coming to school, more self-confident and have stronger skills having a good relationship with others (NSCDC, 2004). When relationships are secure and stable the child’s social skills to support interactions are strengthened, along with the ability to express and manage feelings and emotions.

It is also important to understand that the relationships children have with other children also inform and influence their behavior. Young children learn from each other how to share, how to participate in shared interactions such as taking turns, the reciprocal acts of giving and receiving, how to respect and accept the needs and wants of others, and how to manage their own impulses.

Simply being around other children, however, is not enough to build the skills for positive behaviors. The development of friendships is critical, as children learn and play more competently in the bond created with friends rather than when they are dealing with the social challenges of interacting with casual acquaintances or unfamiliar peers. Positive relationships and positive behaviors all add to healthy brain development and depend upon the relationships with individuals in the child’s close community as well as in the family (Harvard, 2006).

It is within that context of family that we must remember that everything we think, say, and do is processed through our own individual lens and our unique cultural backgrounds. For teachers it is essential to see and understand your own culture to see and understand how the cultures of children and their families influence children’s behavior. Only then can you give every child a fair chance to succeed (Kaiser, Raminsky, 2020).

According to Kaiser and Raminsky, your culture and the children’s cultures are not the only cultures at work in your classroom. Every school and early childhood education program has a culture too. The cultures of most American schools are based on White European American values. As the makeup of the US population becomes more diverse, there is more cultural dissonance—which impacts children’s behavior.

White European American culture has an individual orientation that teaches children to function independently, stand out, talk about themselves, and view property as personal. In contrast, many other cultures value interdependence, fitting in, helping others, and being helped, being modest, and sharing property. In fact, some languages have no words for I, me, or mine. (sbs.com.au)

Children who find themselves in an unfamiliar environment—such as a classroom that reflects a culture different from their home culture—are likely to feel confused, isolated, alienated, conflicted, and less competent because what they have learned so far in their home culture simply does not apply. They may not understand the rules, or they may be unable to communicate their needs in the school’s language. (Kaiser, Rasminsky)

Since the way you respond to children’s behavior and conflict is bound to your own culture, it is common to get the wrong idea about a child’s words or behaviors. When you observe a child’s behavior that is noncompliant, ask yourself if that behavior could be culturally influenced. Honest and open conversations with the family will help you understand and respect their cultural beliefs and practices regarding education and child development.

In terms of relationships, when you as the teacher are responsive to the children’s culture you are better able to form genuine and caring relationships with the children and their families. You can scaffold on this to build on what the child already knows and can do and identify their next steps for learning. This information will help you choose and implement appropriate activities and strategies that honor children’s cultures as well as life experiences and teach children what they need to know and do to be successful in the world today. (Kaiser, Rasminsky).

The Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL) outlines the fundamental importance of positive relationships in an article by Drs. Gail Joseph and Phillip Strain. When adults invest time and effort to teaching proactively prior to behavior “events” children are more successful in achieving improved behavior change, even in situations that might lead to escalating challenging behavior. The key is communicating non-contingent affection and unquestioned valuing of children. The bottom line is that success is dependent on building a positive relationship first. Adults need to invest the time and attention with children as a precedent to the optimum use of sound behavior change strategies (CSEFEL).

The first step is to invest the time in relationship building, and the second is to understand that as your relationships with the child become stronger, so does your potential influence on their behavior. Children will “cue in” on the presence of you as a meaningful and caring adult and will attend differentially and selectively to what you say and do, continuing to seek out ways to ensure even more positive attention from the adult (Lally, Mangione, & Honig).

Review these strategies as you work to build relationships with children, adapted from work by Drs. Joseph and Strain (CSEFEL):

- Offer children a choice as much as possible vs. asking for compliance. Instead of saying “it’s time to clean up,” ask the child if she would like to put the blocks in the basket or the cars on the shelf.

- Take time to reflect to determine if you might ignore some forms of challenging behavior (for example a child’s loud voice), which is simply a decision about where and when to intervene. Note that this is different “planned ignoring” for behavior designed to elicit attention.

- Be aware of your own behaviors and expectations. Set appropriate goals for behavior and determine a way (a counter or visual reminder) to make and track multiple and ongoing relationship deposits.

There will be times that you should and will need to give feedback to children that is in the form of correction and reminders. This will not hinder your relationship building. The important take-away is that your positive interactions need to happen in a greater number and frequency. As you learn to do this you can begin to keep a tally of how many times you remind a child about an unwanted behavior. The goal is for you to find at least twice the number of positive things to comment on and tally those also (CSEFEL).

When children do not receive positive feedback, they are less likely to enter the positive cycle of motivation and learning. The conclusion here is that when children have positive interactions with teachers and other adults, they have fewer instances of challenging behavior. When children feel safe and understood they can use those positive interactions to help build positive relationships. This will build motivation and stimulates within the brain a cycle of repetition focused on motivation and learning.

Social and Emotional Connections to Behavior

As children grow and learn to be in the world, they learn the skills needed to take turns, help their friends, play together, and cooperate with others. Around the same time, children are learning about their own feelings and emotions.

Children are born with the need and desire to connect with those around them. This is social development. When teachers and providers establish positive relationships with children from birth through the early years, and value their diverse cultures and languages, children feel safe and secure, laying the foundation for healthy social and emotional development.

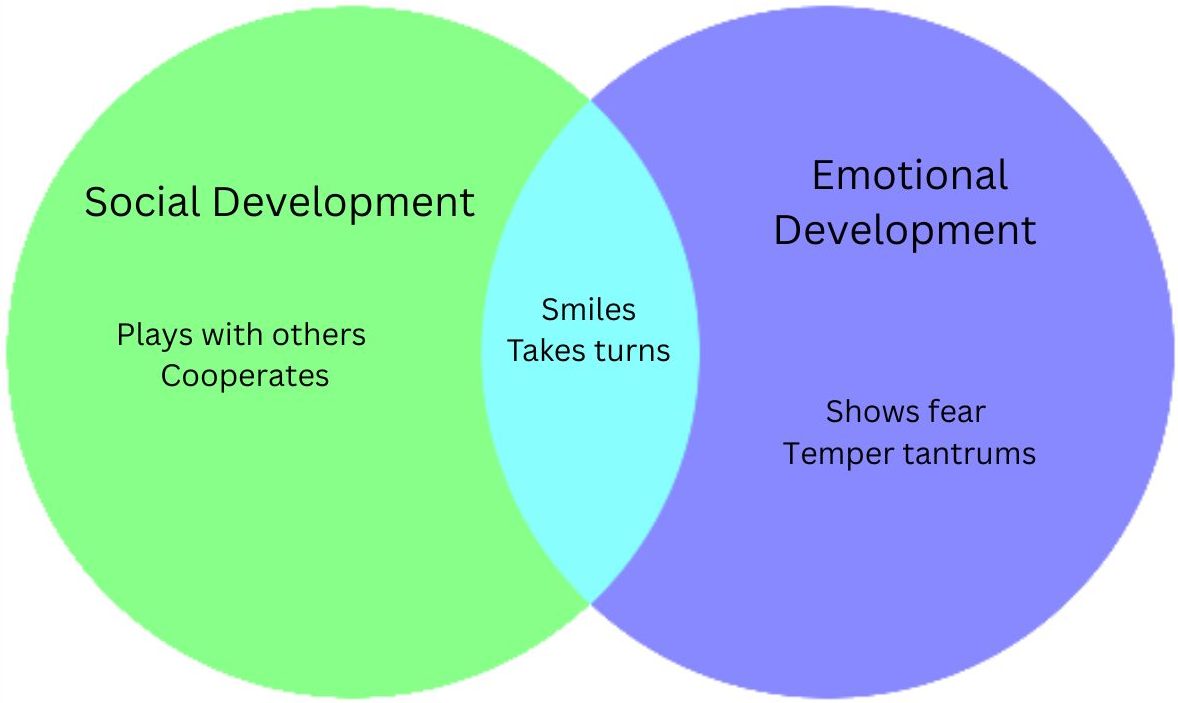

This process affects how children experience the world, express themselves, manage their emotions, and establish positive relationships with others, which is emotional development. Emotional awareness is the ability to recognize and identify our own feelings and actions along with the feelings and actions of other people and understand how our own feelings and actions affect ourselves and others. Review this example of how a Venn Diagram can be used to show some of the discrete social development milestones and emotional development milestones, as well as the intersection (overlap) between the two.

Checkout examples of social and emotional developmental milestones as they relate to behavior:

|

Age |

Examples of social and emotional developmental milestones |

|

Birth to 2 Months |

May briefly calm himself (may bring hands to mouth and suck on hand). Tries to make eye contact with caregiver. Begins to smile at people. |

|

4 Months |

May smile spontaneously, especially at people. Likes interacting with people and might cry when the interaction stops. Copies some movements and facial expressions, like smiling or frowning. |

|

6 Months |

Reacts positively to familiar faces and begins to be wary of strangers. Likes to play with others, especially parents and other caregivers. Responds to own name. |

|

9 Months |

May show early signs of separation anxiety and may cry more often when separated from caregiver and be clingy with familiar adults. May become attached to specific toys or other comfort items. Understands “no.” Copies sounds and gestures of others. |

|

12 Months |

May show fear in new situations. Repeats sounds or actions to get attention. May show signs of independence and resist a caregiver’s attempt to help. Begins to follow simple directions. |

|

18 Months |

May need help coping with temper tantrums. May begin to explore alone but with parent close by. Engages in simple pretend or modeling behavior, such as feeding a doll or talking on the phone. Demonstrates joint attention; for example, the child points to an airplane in the sky and looks at caregiver to make sure the caregiver sees it too. |

|

2 Years |

Copies others, especially adults and older children. Shows increased independence and may show defiant behavior. Mainly plays alongside other children (parallel play) but is beginning to include other children in play. Follows simple instructions. |

|

3 Years |

May start to understand the idea of “mine” and “his” or “hers.” May feel uneasy or anxious with major changes in routine. May begin to learn how to take turns in games and follows directions with 2-3 steps. Names a friend and may show concern for a friend who is sad or upset. |

|

4 Years |

Cooperates with other children and may prefer to play with other children than by herself. Often cannot tell what is real and what is make-believe. Enjoys new things and activities. |

|

5 Years |

May want to please caregivers and peers. Is aware of gender. May start recognizing what is real and what is make-believe. |

|

6-7 Years |

Measure his performance against others. Continue to develop her social skills by playing with other children in a variety of situations. Be able to communicate with others without adult help. Start to feel sensitive about how other children feel about him. |

Social and emotional development involve several interrelated areas of development, including social interaction, emotional awareness, and self-regulation. Below are examples of important aspects of social and emotional development for young children.

Social interaction focuses on the relationships we share with others, including relationships with adults and peers. As children develop socially, they learn to take turns, help their friends, play together, and cooperate with others. Emotional awareness includes the ability to recognize and understand our own feelings and actions and those of other people, and how our own feelings and actions affect ourselves and others. Self-regulation is the ability to express thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in socially appropriate ways. Learning to calm down when angry or excited and persisting at difficult tasks are examples of self-regulation.

Children who are socially and emotionally healthy tend to demonstrate, and continue to develop, several important behaviors and skills (adapted from McClellan & Katz 2001 and Bilmes 2012). According to these three authors, children

- Are usually in a positive mood

- Listen and follow directions

- Have close relationships with caregivers and peers

- Recognize, label, and manage their own emotions

- Understand others’ emotions and show empathy

- Express wishes and preferences clearly

- Gain access to ongoing play and group activities

- Ability to play, negotiate, and compromise with others

Social and emotional development are both related to behavior, and include the areas of social interaction, emotional awareness, and self-regulation. Social interaction spotlights the relationships children share with others and includes relationships with adults and other children. As children develop socially, they learn the skills needed to take turns, help their classmates, play together, and cooperate with others.

|

|

Reflection Affirm the Child, Not the Behavior Read the quote by Dan Cartell, 2020. Explain what it means to you. What are some specific examples of how you would do this in the classroom? |

Direct and Indirect Guidance

Direct guidance and indirect guidance are two methods that early childhood educators (ECEs) use to help young children learn in a safe and engaging environment. Both guidance methods have their advantages in and outside of the classroom. Yet, they are not the same. These teaching methods are used as part of positive guidance.

What is Indirect Guidance?

Young children are highly influenced by their environment. This includes sounds, visuals, objects, and even the people in the same room as them. These indirect factors can disrupt a child’s behavior. So, it is essential to use positive guidance techniques to create a safe learning environment.

These factors are thought about when arranging a classroom, setting class rules, and designing lesson plans. This is called indirect guidance, and it is a preventative guidance technique. By indirectly influencing a child’s behavior through their physical space, e.g., providing enough learning materials, we can teach young children how to behave in different social situations.

What is Direct Guidance?

On the other hand, direct guidance is a method used to respond to a child’s inappropriate behavior as it happens. This guidance strategy uses verbal and non-verbal communication to help young children acknowledge their wrong or mistaken behavior and correct it.

The direct guidance technique involves teachers using simple language or actions in a relaxed manner to help children understand how they should behave. This can be done in many ways, but the most popular methods are modeling behavior or redirecting a child’s attention. Direct guidance is a reactive approach.

How Are These Guidance Strategies Used in the Early Learning Setting?

One of the best ways to understand these early childhood guidance strategies is through real-life examples. If you have ever wondered how direct and indirect guidance is used in your child’s early learning center, we will enlighten you.

Here are a few of our favorite direct guidance and indirect guidance examples to use:

Direct Guidance Examples

- Offer children choices: If a child is misbehaving, redirect their attention by giving them a choice between two appropriate behaviors. For example, ask them, “Do you want to read a book in this chair, or do you want to play with the building blocks?” This helps them to choose a more suitable activity to do.

- Redirecting their attention: Redirecting a child’s attention is another excellent way to assist them in making thoughtful choices. For example, when a child is moving something they shouldn’t be, say, “Ben, the paints stay in the arts and crafts section. This is where we read books. Let’s go over to the bookshelves and choose a story to read together.”

- Encourage them to solve problems: Facilitating problem-solving is another effective direct guidance example. If there is a conflict with another child, ask them to explain the problem and how it can be solved. This helps them learn how to navigate conflicts.

- Intervene: If a child is misbehaving and not listening to your guidance, intervention may be necessary. Changing their physical environment can help, e.g., move them to a different area of the room, provide more materials, or remove certain toys or equipment.

Indirect Guidance Examples

- Change the physical space: Make the classroom environment as child-friendly and learning-friendly as possible. Have different learning sections, so they know that one area of the room is for playing and another is for building scientific inquiry skills. Place learning materials and other furniture at the child’s height. For example, bookshelves should be at eye level so a child can choose their own book.

- Provide consistent schedules: Children love consistency as it makes them feel safe. Including fun and engaging activities into their daily routine can help reduce misbehaving. Include various activities that will help them develop early learning skills while also encouraging them to explore their own interests.

- Have set class rules: Children need structure, which also applies to the classroom rules. Having consistent rules the children must follow, e.g., “we walk in the classroom, we run when we’re outside,” helps them understand what is expected of them.

Final Thoughts

We will look at behavior again in another chapter when we look at the classroom environment and real life supports.