6 Music Recording, “Sharing” and the Information Economy

“I definitely wanted to earn my freedom. But the primary motivation wasn’t making money, but making an impact.” — Sean Parker, Napster co- founder, Spotify board member and former Facebook president

The Recording Industry as Harbinger of Digital Disruption

By reputation, the recording industry is rife with schmucks and cheats, gangsters and goons. It is also one of the most important cultural industries of all time. Popular music reflects and shapes our culture, provides a soundtrack for our lives and loves, and builds the emotional framework for our best and worst moments. Some music producers have a reputation for being unscrupulous and for caring more about making money than making music. Mob involvement in the industry is well-documented. This is not to say that the industry is completely corrupt; it is true, however, that corruption is an ongoing problem.

Still, most of us have a favorite genre of music and at least a dozen favorite artists. It is rare that you will love a film but hate the soundtrack. It is more rare, perhaps, to find a person who cannot tell you which songs were popular when they were in high school and what kind of music they would like at their wedding reception. For a speed run through the history of popular recorded music, check out this video. The link goes to a YouTube presentation tracking the “Evolution of Popular Music by Year.” The list of performers can be found in this blog post, which notes the gender balance in pop music over the years, as well as a few other brief highlights.

This chapter about recorded music focuses mostly on the changing industry. But as you consider the industry from an academic perspective, don’t lose sight of your relationship with music. What you enjoy is an expression of yourself and of your personal culture. Preserving the emotional impact of music should concern us all, even if we are more or less enthusiastic about preserving the old order of the recording industry and the interests of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). We’ll begin by briefly visiting recording industry history before touring popular music throughout the decades.

Recording Industry History

The RIAA built a reputation for suing individual users of file sharing sites for making songs protected under copyright available to other users. A discussion about recorded music in the digital age quickly becomes a discussion about copyright. The RIAA is a trade organization. It was formed to protect record labels and their products. It fought file “sharing” — the free digital distribution of music files, most often in MP3 format — with limited success in the early 2000s. By suing consumers for making music files available online, the Association cracked down on digital music piracy somewhat, but it also angered a generation of music consumers. Around the same time that the RIAA became known for suing users for sharing music, it was sued for alleged antitrust violations related to downloading services the industry had launched. Specifically, record labels were accused of artificially inflating the prices of music downloads on services they had established. The case was dismissed by the U.S. Supreme Court. Music distributors lost a separate $143 million case that found they illegally inflated the price of CDs in the late 1990s. The RIAA is both a staunch protector of artists’ copyright-protected material and a monopolistic trade group.

A Detour Through Disney to Discuss Copyright

View the video below for a unique take on what copyright is and how it currently functions. The film does not argue that the illegal downloading and sharing of music files is fair use, but it does suggest that intellectual property copyright protections might be designed to protect corporate profits over creative endeavors.

There will always be a battle between creators, who value the disruption of previous regimes in favor of developing new products on new platforms that remediate previous works, and original producers, who want to preserve the right to earn money from their creative works. As a reminder, remediation is taking existing media content and concepts and using them in new media platforms. It may include mashups of existing content, sampling, stacking and compiling. Remediation works with many forms of media, but much of the content that cutting-edge creative producers want to use is still under copyright. At issue is under what circumstances is remediation considered fair use of material under copyright and under what circumstances does remediation violate copyright. This text does not offer a simple answer. Please note, however, that this text itself is presented on an open platform with a CCBY copyright license. The author was not paid for creating this text, but if others can rework parts of it into profitable products, that is allowed. This ensures that this text will always be available for all to use, repurpose, build on or subtract from. The author works in a nonprofit academic setting, and the incentive is to earn tenure by publishing this and other works. This form of publishing under a Creative Commons license is growing in popularity, but it cannot be expected of those working in for-profit media industries.

At the root of copyright law is whether a new work hurts the market value of the original work (assuming the original is not yet in the public domain). This question is sometimes settled on a case- by-case basis. Before students as would-be disruptors begin to think the system is unfair, they must remember that their own products will be protected by copyright. Weak copyright law makes it easy for works to be altered slightly and republished with little or no gain going to the creator. Aspiring mass communication professionals often find themselves tied in conceptual knots over how to think about copyright law. A few suggestions: Obey it without letting it stop you from producing works you love. Work around violations and assume your digital work will be open to disruption and copying the moment it is made public.

The film Downloaded directed by Alex Winter (Ted of Bill & Ted fame) documents the battle between the founders of Napster and the RIAA in the first major intellectual property battle of the digital age. The entire recording industry was shaken up by young college students who identified as hackers. The RIAA won the battle against Napster but lost the war against digital music sharing and the formation of digital music platforms. Apple’s iTunes legitimized digital music sharing. Spotify and Pandora created legal means for people to consume mass amounts of digital content for free. For a fee, you can usually access most of the music you want, and you can create playlists from massive music databases that put pre-digital download music collections to shame.

On the other hand, there has been something of a backlash against digital music downloading as a new generation of audiophiles discover the LP record as a means of owning physical copies of the music they love. Records can be owned and cherished, but they are also cumbersome. Digital music is ubiquitous but the sound quality is often lacking, and maintaining a digital library takes effort and often an investment in cloud storage. One way or another, if you want to hold onto recorded music for your own personal use, you are probably going to have to pay. Even if you use YouTube as your own personal music collection, when you search for a specific song you will often pay with your attention by watching pre-roll ads.

The recording industry and many artists would argue that of course music should not be available for free. It costs time and effort to create popular professional music. On the other hand, the recording industry is notorious for not paying artists. Much of the money to be made in professional music comes from live performances and merchandise sales. An option for artists is to release their music for free and use it to garner attention and bring people into live shows where they can sell apparel, artistic LPs and CD box sets to “true” fans for a greater percentage of the profit.

As consumers, you should be aware of where your money goes when you pay for music and who benefits from the attention you pay to advertisers when you do not pay for music. The popularity of Pandora and Spotify helped drive radio broadcasting conglomerates to act more like streaming services. The iHeartRadio app, for example, is a paid app that gives you a digital connection to a host of radio stations and podcasts. It takes something that was free — over-the-air radio — and makes it a paid service, albeit with added features and convenience.

The broadcast industry will be discussed more in the next chapter. For now, it is enough to understand that in the history of broadcasting in the United States, there is a long tradition of production and distribution companies either directly collaborating or being one and the same. The people who made radio also made recorded music or had close relationships with those who did, and they could determine what music and other programming went over the air. This is different from agenda setting where messages in the mass media can set the bulk of the public’s political agenda. This is a matter of keeping messages off the air that are considered too disruptive or radical. In some countries, the airwaves are directly regulated by the government. In the U.S., closely watched monopolies give the appearance that the government is not censoring music, but in essence, the monopolies do it for them. Before there were Napster “pirates,” there was pirate radio. The freedom for an individual to play the songs they want to play when they want to play them over the airwaves for public consumption has not existed since the very early days of radio. Consider this the next time you build and share a Spotify playlist (or, if you’re old school, make a mixtape).

Music monopolies existed with government support and were justified as being necessary, particularly during times of war when leaders wanted to keep tight control over messages. When political will built up in support of splitting mass media monopolies in favor of protecting the intent of the First Amendment, antitrust laws were used; however, if history shows anything it is that powerful people in media seek to consolidate their power. In other words, we should expect music broadcasters to attempt to form monopolies, even as existing radio broadcasting conglomerates such as iHeart Radio face hard times.

The Evolution of Popular Music 1920s to 1960s

The first stirrings of popular or pop music—any genre of music that appeals to a wide audience or subculture—began in the late 19th century, with discoveries by Thomas Edison and Emile Berliner. In 1877, Edison discovered that sound could be reproduced using a strip of tinfoil wrapped around a rotating metal cylinder. Edison’s phonograph provided ideas and inspiration for Berliner’s gramophone, which used flat discs to record sound. The flat discs were cheaper and easier to produce than were the cylinders they replaced, enabling the mass production of sound recordings. This would have a huge impact on the popular music industry, enabling members of the middle class to purchase technology that was previously available only to an elite few. Berliner founded the Berliner Gramophone Company to manufacture his discs, and he encouraged popular operatic singers such as Enrico Caruso and Dame Nellie Melba to record their music using his system. Opera singers were the stars of the 19th century, and their music generated most of the sheet music sales in the United States. Although the gramophone was an exciting new development, it would take 20 years for disc recordings to rival sheet music in commercial importance (Shepherd, 2003).

In the late 19th century, the lax copyright laws that existed in the United States at the beginning of the century were strengthened, providing an opportunity for composers, singers, and publishers to work together to earn money by producing as much music as possible. Numerous publishers began to emerge in an area of New York that became known as Tin Pan Alley. Allegedly named because the cacophony of many pianos being played in the publishers’ demo rooms sounded like people pounding on tin pans, Tin Pan Alley soon became a prolific source of popular music, with its publishers mass-producing sheet music to satisfy the demands of a growing middle class.

Whereas classical artists were exalted for their individuality and expected to differ stylistically from other classical artists, popular artists were praised for conforming to the tastes of their intended audience. Popular genres expanded from opera to include vaudeville—a form of variety entertainment containing short acts featuring singers, dancers, magicians, and comedians that opened new doors for publishers to sell songs popularized by the live shows—and ragtime, a style of piano music characterized by a syncopated melody.

The Tin Pan Alley tradition of song publishing continued throughout the first half of the 20th century with the show tunes and soothing ballads of Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, and George Gershwin, and songwriting teams of the early 1950s, such as Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. By hiring songwriters to compose music based on public demand and mainstream tastes, the Tin Pan Alley publishers introduced the concept of popular music as we know it.

The Roaring 1920s: Radio versus Records

In the 1920s, Tin Pan Alley’s dominance of the popular music industry was threatened by two technological developments: the advent of electrical recording and the rapid growth of radio.

During the early days of its development, the gramophone was viewed as a scientific novelty that posed little threat to sheet music because of its poor sound quality. However, as inventors improved various aspects of the device, the sales of gramophone records began to affect sheet music sales. The Copyright Act of 1911 had imposed a royalty on all records of copyrighted musical works to compensate for the loss in revenue to composers and authors. This loss became even more prominent during the mid-1920s, when improvements in electrical recording drastically increased sales of gramophones and gramophone records. The greater range and sensitivity of the electrical broadcasting microphone revolutionized gramophone recording to such an extent that sheet music sales plummeted. From the very beginning, the record industry faced challenges from new technology.

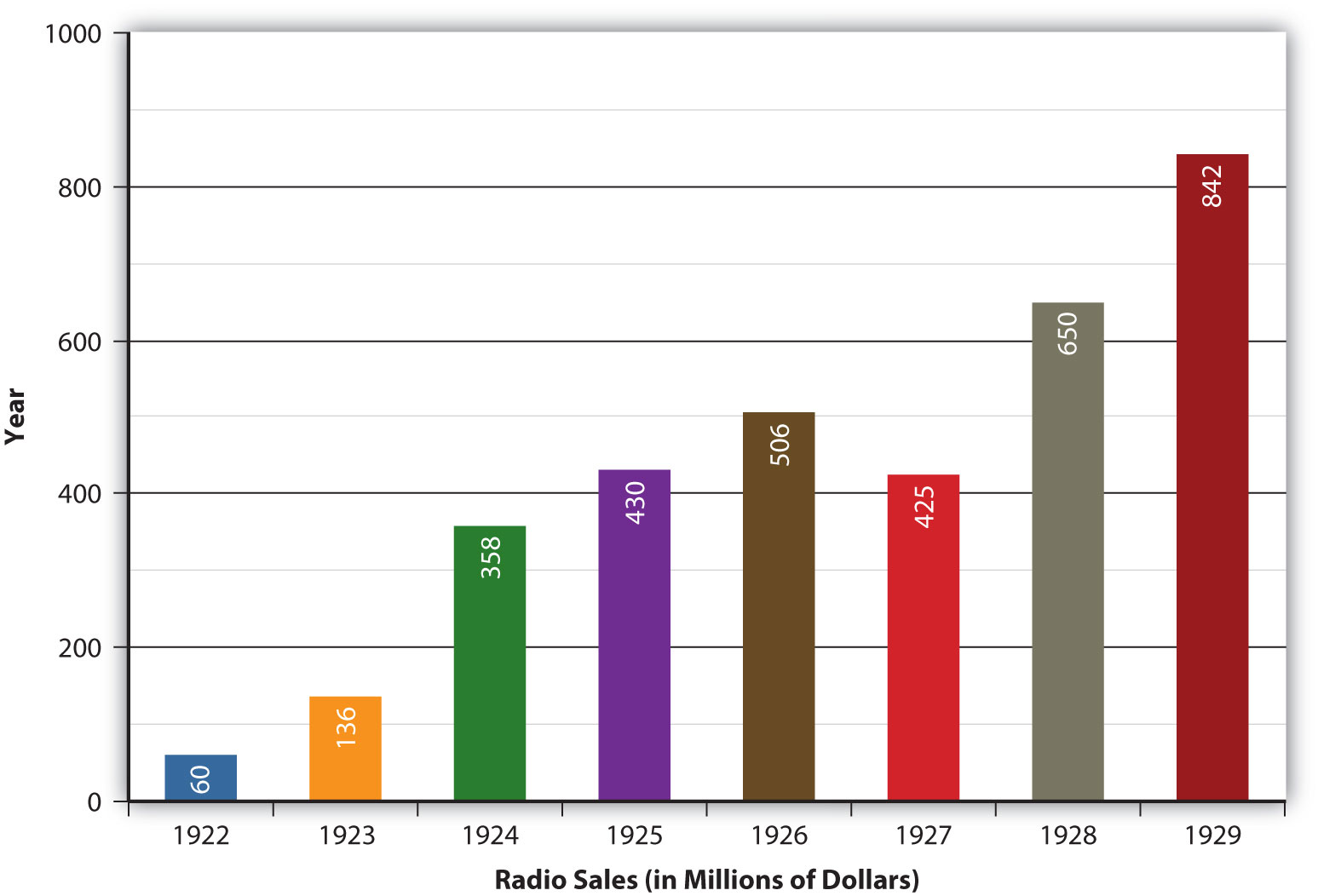

Radio sales dramatically increased throughout the 1920s because radios were an affordable way to listen to free music and live events.

Composers and publishers could deal with the losses caused by an increase in gramophone sales because of the provisions made in the Copyright Act. However, when radio broadcasting emerged in the early 1920s, both gramophone sales and sheet-music sales began to suffer. Radio was an affordable medium that enabled listeners to experience events as they took place. Better yet, it offered a wide range of free music that required none of the musical skills, expensive instruments, or sheet music necessary for creating one’s own music in the home, nor the expense of purchasing records to play on the gramophone. This development was a threat to the entire recording industry, which began to campaign for, and was ultimately granted, the right to collect license fees from broadcasters. With the license fees in place, the recording industry eventually began to profit from the new technology

The 1930s: The Rise of Jazz and Blues.

The ascendance of Tin Pan Alley coincided with the emergence of jazz in New Orleans. An improvisational form of music that was primarily instrumental, jazz incorporated a variety of styles, including African rhythms, gospel, and blues. Established by New Orleans musicians such as King Oliver and his protégé, Louis Armstrong, who is considered by many to be one of the greatest jazz soloists in history, jazz spread along the Mississippi River by the bands that traveled up and down the river playing on steamboats. During the Prohibition era in the 1920s and early 1930s, some jazz bands played in illegal speakeasies, which helped generate the genre’s reputation for being immoral and for threatening the country’s cultural values. However, jazz became a legitimate form of entertainment during the 1930s, when White orchestras began to incorporate jazz style into their music. During this time, jazz music began to take on a big band style, combining elements of ragtime, Black spirituals, blues, and European music. Key figures in developing the big jazz band included bandleaders Duke Ellington, Coleman Hawkins, and Glenn Miller. These big band orchestras used an arranger to limit improvisation by assigning parts of a piece of music to various band members. Although improvisation was allowed during solo performances, the format became more structured, resulting in the swing style of jazz that became popular in the 1930s. As the decade progressed, social attitudes toward racial segregation relaxed and big bands became more racially integrated.

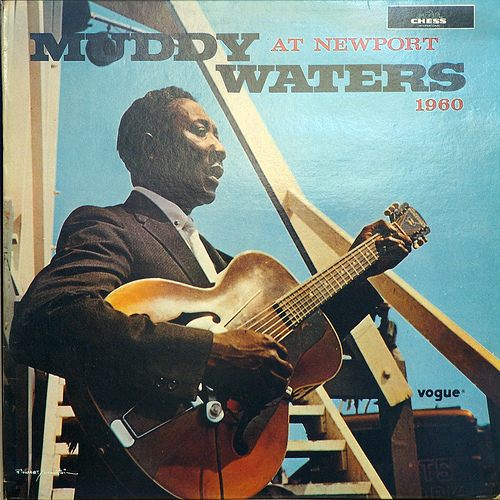

At the heart of jazz, the blues was a creation of former Black slaves who adapted their African musical heritage to the American environment. Dealing with themes of personal adversity, overcoming hard luck, and other emotional turmoil, the blues is a 12-bar musical form with a call-and-response format between the singer and his guitar. Originating in the Mississippi Delta, just upriver from New Orleans, blues music was exemplified in the work of W. C. Handy, Ma Rainey, Robert Johnson, and Lead Belly, among others. Unlike jazz, the blues did not spread significantly to the Northern states until the late 1930s and 1940s. Once Southern migrants introduced the blues to urban Northern cities, the music developed into distinctive regional styles, ranging from the jazz-oriented Kansas City blues to the swing-based West Coast blues. Chicago blues musicians such as Muddy Waters were the first to electrify the blues through the use of electric guitars and to blend urban style with classic Southern blues. The electric guitar, first produced by Adolph Rickenbacker in 1931, changed music by intensifying the sound and creating a louder volume that could cut through noise in bars and nightclubs (Rickenbacker, 2010). By focusing less on shouting, singers could focus on conveying more emotion and intimacy in their performances. This electrified form of blues provided the foundations of rock and roll.

The Chicago blues, characterized by the use of electric guitar and harmonica,provided the foundations of rock and roll. Muddy Waters was one of the most famous Chicago blues musicians. The 1920s through the 1950s is considered the golden age of radio. During this time, the number of licensed radio stations in the United States exploded from five in 1921 to over 600 by 1925 (Salmon, 2010). The introduction of radio broadcasting provided a valuable link between urban city centers and small, rural towns. Able to transmit music nationwide, rural radio stations broadcasted local music genres that soon gained popularity across the country.

The 1940s: Technology Progresses

Technological advances during the 1940s made it even easier for people to listen to their favorite music and for artists to record it. The introduction of the reel-to-reel tape recorder paved the way for several innovations that would transform the music industry. The first commercially available tape recorders were monophonic, meaning that they only had one track on which to record sound onto magnetic tape. This may seem limiting today, but at the time it allowed for exciting innovations. During the 1940s and 1950s, some musicians—most notably guitarist Les Paul, with his song “Lover (When You’re Near Me)”—began to experiment with overdubbing, in which they played back a previously recorded tape through a mixer, blended it with a live performance, and recorded the composite signal onto a second tape recorder. By the time four-track and eight-track recorders became readily available in the 1960s, musicians no longer had to play together in the same room; they could record each of their individual parts and combine them into a finished recording.

While the reel-to-reel recorders were in the early stages of development, families listened to records on their gramophones. The 78 revolutions per minute (rpm) disc had been the accepted recording medium for many years despite the necessity of changing the disc every 5 minutes. In 1948, Columbia Records perfected the 12-inch 33 rpm long-playing (LP) disc, which could play up to 25 minutes per side and had a lower level of surface noise than the earlier (and highly breakable) shellac discs (Lomax, 2003). The 33 rpm discs became the standard form for full albums and would dominate the recorded music industry until the advent of the compact disc (CD).

During the 1940s, a mutually beneficial alliance between sound recording and radio existed. Artists such as Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald profited from radio exposure. Until this time, music had primarily been recorded for adults, but the popularity of Sinatra and his contemporaries revealed an entirely untapped market: teenagers. The postwar boom of the 1930s and early 1940s provided many teenagers spending money for records. Radio airplay helped to promote and sell records and the recording artists themselves, which in turn stabilized the recording industry. The near riots caused by the appearance of New Jersey crooner Frank Sinatra in concert paved the way for mass hysteria among Elvis Presley and Beatles fans during the rock and roll era.

The 1950s: The Advent of Rock and Roll

New technology continued to develop in the 1950s with the introduction of television. The new medium spread rapidly, primarily because of cheaper mass-production costs and war-related improvements in technology. In 1948, only 1 percent of America’s households owned a television; by 1953 this figure had risen to nearly 50 percent, and by 1978 nearly every home in the United States owned a television (Genova). The introduction of television into people’s homes threatened the existence of the radio industry. The radio industry adapted by focusing on music, joining forces with the recording industry to survive. In an effort to do so, it became somewhat of a promotional tool. Stations became more dependent on recorded music to fill airtime, and in 1955 the Top 40 format was born. Playlists for radio stations were based on popularity (usually the Billboard Top 40 singles chart), and a popular song might be played as many as 30 or 40 times a day. Radio stations began to influence record sales, which resulted in increased competition for spots on the playlist. This ultimately resulted in payola—the illegal practice of receiving payment from a record company for broadcasting a particular song on the radio. The payola scandal came to a head in the 1960s, when Cleveland, Ohio, DJ Alan Freed and eight other disc jockeys were accused of taking money for airplay. Following Freed’s trial, an antipayola statute was passed, making payola a misdemeanor crime.

Technology wasn’t the only revolution that took place during the 1950s. The urban Chicago blues typified by artists such as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and B. B. King surged in popularity among White and Black teenagers alike. Marketed under the name rhythm and blues, or R&B, the sexually suggestive lyrics in songs such as “Sexy Ways” and “Sixty Minute Man” and the electrified guitar and wailing harmonica sounds appealed to young listeners. At the time, R&B records were classified as “race music” and their sales were segregated from the White music records tracked on the pop charts (Szatmary, 2010). Nonetheless, there was a considerable amount of crossover among audiences. In 1952, the Dolphin’s of Hollywood record store in Los Angeles, which specialized in R&B music, noted that 40 percent of its sales were to White individuals (Szatmary, 2010).

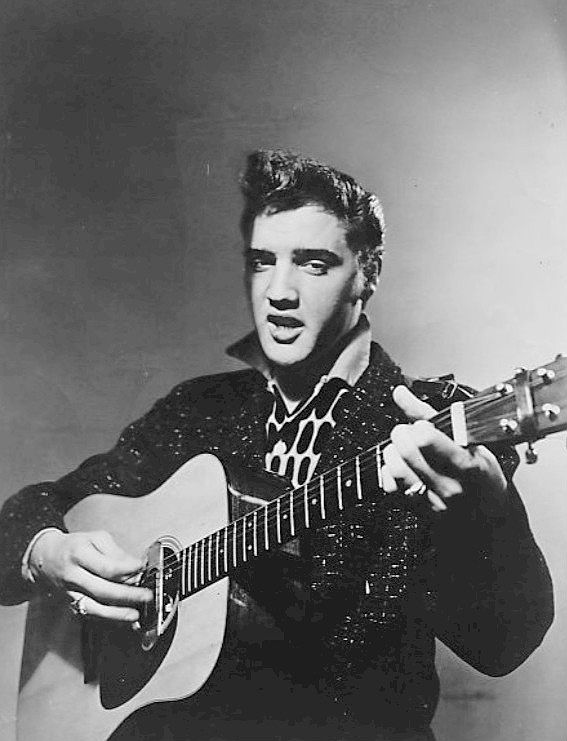

Although banned from some stations, others embraced the popular new music. In 1951, Freed started a late-night R&B show called The Moondog Rock & Roll House Party and began referring to the music he played as rock and roll (History Of Rock). Taking its name from a blues slang term for sex, the music obtained instant notoriety, gaining widespread support among teenage music fans and widespread dislike among the older generation (History Of Rock). Frenetic showmen Little Richard and Chuck Berry were early pioneers of rock and roll, and their wild stage performances became characteristic of the genre. As the integration of White and Black individuals progressed in the 1950s with the repeal of segregation laws and the initiation of the civil rights movement, aspects of Black culture, including music, became more widely accepted by many White individuals. However, it was the introduction of a White man who sang songs written by Black musicians that helped rock and roll really spread across state and racial lines. Elvis Presley, a singer and guitarist, the “King of Rock and Roll,” further helped make music written by Black individuals acceptable to mainstream White audiences and also helped popularize rockabilly—a blend of rock and country music—with Black audiences during the mid-1950s. Heavily influenced by his rural Southern roots, Presley combined the R&B music of bluesmen B. B. King, John Lee Hooker, and Howlin’ Wolf with the country-western tradition of Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb, and Jimmie Rodgers, and added a touch of gospel (Elvis). The reaction Presley inspired among hordes of adolescent girls—screaming, crying, rioting—solidified his reputation as the first true rock and roll icon.

The 1960s: Rock and Roll Branches Out From R&B

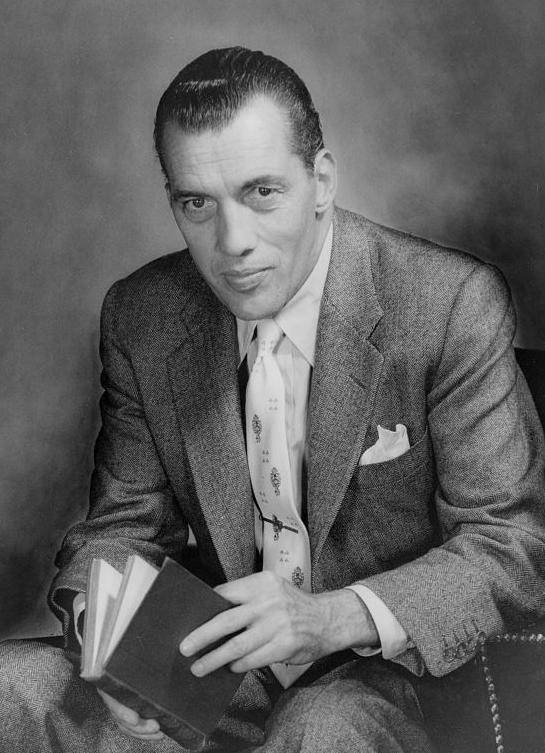

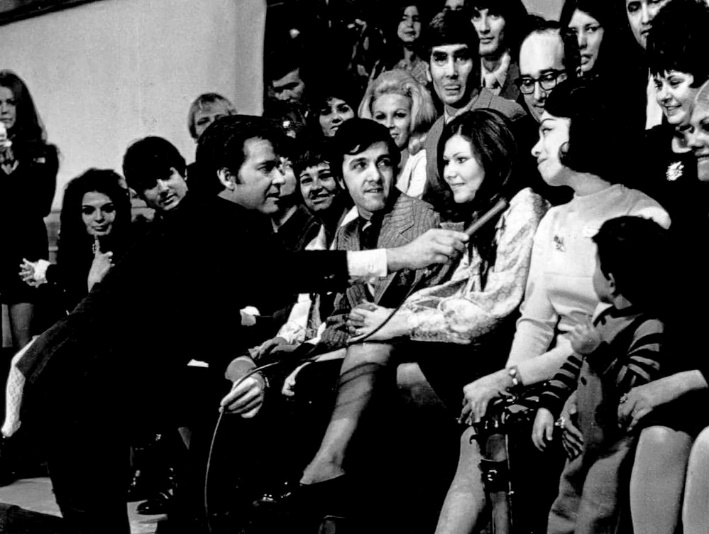

Prior to 1964, rock and roll was primarily an American export. Although U.S. artists frequently reached the top of the charts overseas, few European artists achieved success on this side of the Atlantic. This situation changed almost overnight with the arrival of British pop phenomenon the Beatles. Combining elements of skiffle—a type of music played on rudimentary instruments, such as banjos, guitars, or homemade instruments—doo-wop, and soul, the four mop-haired musicians from Liverpool, England, created a genre of music known as Merseybeat, named after the River Mersey. The Beatles’ genial personalities and catchy pop tunes made them an instant success in the United States, and their popularity was heightened by several appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show. When the Beatles arrived in New York in 1964, they were met by hundreds of reporters and police officers and thousands of fans. Their appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show a few days later was the largest audience for an American television program, with approximately one in three Americans (74 million) tuning in (Gould, 2007). Beatlemania—the term coined to describe fans’ wildly enthusiastic reaction to the band—extended to other British bands, and by the mid-1960s, the Kinks, the Zombies, the Animals, Herman’s Hermits, and the Rolling Stones were all making appearances on the U.S. charts. The Rolling Stones’ urban rock sound steered away from pop music and remained more true to the bluesy, R&B roots of rock and roll. During their first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, the Stones were lewd and vulgar, prompting host Ed Sullivan to denounce their behavior (although he privately acknowledged that the band had received the most enthusiastic applause he had ever seen) (Ed Sullivan). The British Invasion transformed rock and roll into the all-encompassing genre of rock, sending future performers in two different directions: the melodic, poppy sounds of the Beatles, on the one hand, and the gritty, high-volume power rock of the Stones on the other.

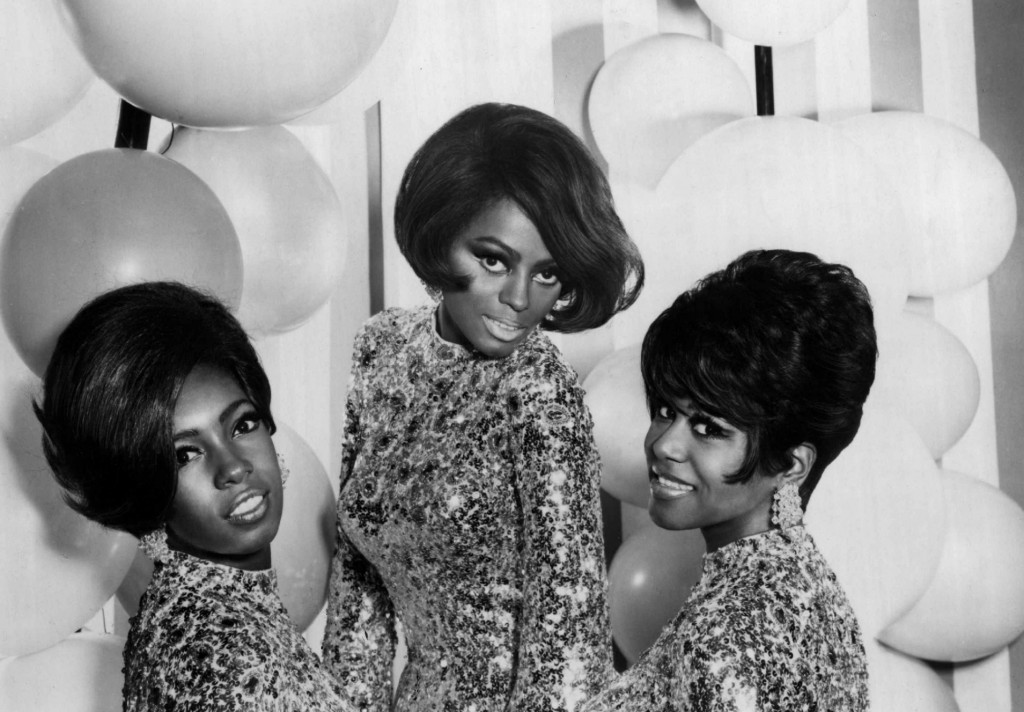

The branching out of rock and roll continued in several other directions throughout the 1960s. Surf music, embodied by artists such as the Beach Boys, Jan and Dean, and Dick Dale, celebrated the aspects of youth culture in California. With their twanging electric guitars and glossy harmonies, the surf groups sang of girls, beaches, and convertible cars cruising along the West Coast. In Detroit, some Black performers were developing a sound that would have crossover appeal with both Black and White audiences. Combining R&B, pop, gospel, and blues into a genre known as soul, vocalists such as James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, and Wilson Pickett sang about the lives of Black Americans. Producer and songwriter Berry Gordy Jr. developed soul music through the creation of his Motown label, which would become one of the most successful businesses owned by a Black individual in American history (Notable Biographies). Capitalizing on the 1960s girl-group craze, Gordy produced hits by the Marvelettes, Martha and the Vandellas, and, most successfully, Diana Ross and the Supremes. For his bands, he created a slick, polished image designed to appeal to the American mainstream.

In the late 1960s, supporters of the civil rights movement—along with feminists, environmentalists, and Vietnam War protesters—were gravitating toward folk music, which would become the sound of social activism. Broadly referring to music that is passed down orally through the generations, folk music retained an unpolished, amateur quality that inspired participation and social awareness. Carrying on the legacy of the 1930s labor activist Woody Guthrie, singer-songwriters such as Joan Baez; Peter, Paul, and Mary; and Bob Dylan sang social protest songs about civil rights, discrimination against Black Americans, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Having earned himself a reputation as a political spokesperson, Dylan was lambasted by traditional folk fans for playing an electric guitar at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. However, his attempt to reach a broader crowd inspired the folk rock genre, pioneered by the Los Angeles band the Byrds (PBS). Even though many fans questioned his decision to go electric, Dylan’s poetic and politically charged lyrics were still influential, inspiring groups like the Beatles and the Animals. Protest music in the 1960s was closely aligned with the hippie culture, in which some viewed taking drugs as a form of personal expression and free speech. Artists such as Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, and the Doors believed that the listening experience could be enhanced using mind-altering drugs (Rounds, 2007). This spirit of freedom and protest culminated in the infamous Woodstock festival in the summer of 1969, although the subsequent deaths of many of its stars from drug overdoses cast a shadow over the psychedelic culture.

The 1970s: From Glam Rock to Punk

After the Vietnam War ended, college students began to settle down and focus on careers and families. For some, selfish views took the place of concern with social issues and political activism, causing writer Tom Wolfe to label the 1970s the “me” decade (Wolfe, 1976). Musically, this ideological shift resulted in the creation of glam rock, an extravagant, self-indulgent form of rock that incorporated flamboyant costumes, heavy makeup, and elements of hard rock and pop. A primarily British phenomenon, glam rock was popularized by acts such as Slade, David Bowie, the Sweet, Elton John, and Gary Glitter. It proved to be a precursor for the punk movement in the late 1970s. Equally flamboyant, but rising out of a more electronic sound, disco also emerged in the 1970s. Popular disco artists included KC and the Sunshine Band, Gloria Gaynor, the Bee Gees, and Donna Summer, who helped to pioneer its electronic sound. Boosted by the success of 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, disco’s popularity spread across the country. Records were created especially for discos, and record companies churned out tunes that became huge hits on the dance floor.

Reacting against the commercialism of disco and corporate rock, punk artists created a minimalist, angry form of rock that returned to rock and roll basics: simple chord structures, catchy tunes, and politically motivated lyrics. Like the skiffle bands of the 1950s, the appeal of punk rock was that anyone with basic musical skills could participate. The punk rock movement emerged out of CBGB, a small bar in New York City that featured bands such as Television, Blondie, and the Ramones. Never a huge commercial success in the United States, punk rock exploded in the United Kingdom, where high unemployment rates and class divisions had created angry, disenfranchised youths (BBC). The Sex Pistols, fronted by Johnny Rotten, developed an aggressive, pumping sound that appealed to a rebellious generation of listeners, although the band was disparaged by many critics at the time. In 1976, British music paper Melody Maker complained that “the Sex Pistols do as much for music as World War II did for the cause of peace (Gray, 2001).” Punk bands began to abandon their sound in the late 1970s, when the punk style became assimilated into the rock mainstream.

The 1980s: The Hip-Hop Generation

Whereas many British youths expressed their displeasure through punk music, many disenfranchised Black American youths in the 1980s turned to hip-hop—a term for the urban culture that includes break dancing, graffiti art, and the musical techniques of rapping, sampling, and scratching records. Reacting against the extravagance of disco, many poor urban rappers developed their new street culture by adopting a casual image consisting of T-shirts and sportswear, developing a language that reflected the everyday concerns of the people in low-income, urban areas, and by embracing the low-budget visual art form of graffiti. They described their new culture as hip-hop, after a common phrase chanted at dance parties in New York’s Bronx borough.

The hip-hop genre first became popular among Black youths in the late 1970s, when record spinners in the Bronx and Harlem started to play short fragments of songs rather than the entire track (known as sampling) (Demers, 2003). Early hip-hop artists sampled all types of music, like funk, soul, and jazz, later adding special effects to the samples and experimenting with techniques such as rotating or scratching records back and forth to create a rhythmic pattern. For example, Kool Moe Dee’s track “How Ya Like Me Now” includes samples from James Brown’s classic funk song “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag.” The DJs would often add short raps to their music to let audiences know who was playing the records, a trend that grew more elaborate over time to include entire spoken verses. Artists such as Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five added political and social commentary on the realities of life in low-income, high-crime areas—a trend that would continue with later rappers such as Public Enemy and Ice-T.

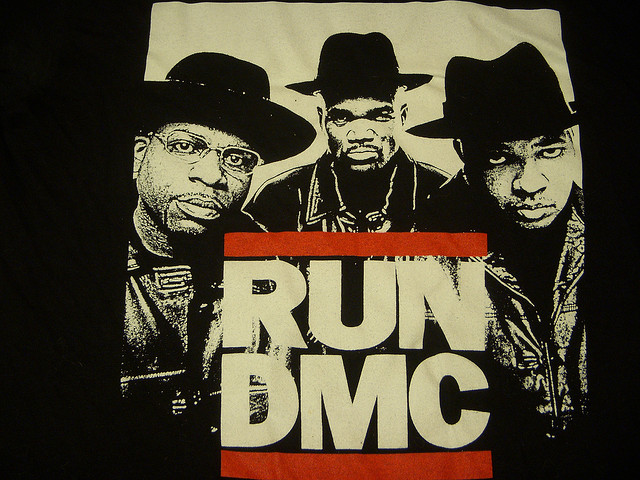

In the early 1980s, a second wave of rap artists brought inner-city rap to American youths by mixing it with hard guitar rock. Pioneered by groups such as Run-D.M.C. and the Beastie Boys, the new music appealed to Black and White audiences alike. Another subgenre that emerged was gangsta rap, a controversial brand of hip-hop epitomized by West Coast rappers such as Ice Cube and Tupac Shakur. Highlighting violence and gang warfare, gangsta rappers faced accusations that they created violence in inner cities—an argument that gained momentum with the East Coast–West Coast rivalry of the 1990s.

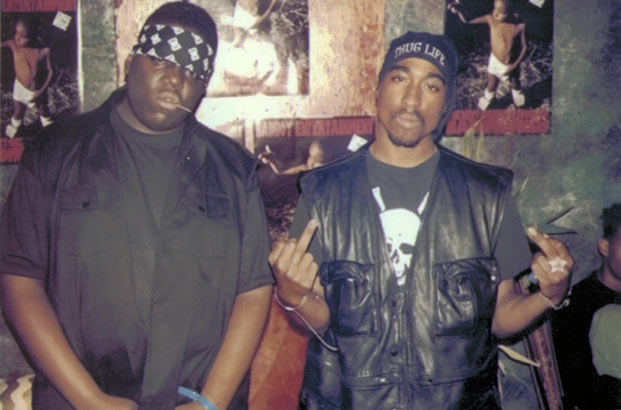

The 1990s: New Developments in Hip-Hop, Rock, and Pop

Hip-hop and gangsta rap maintained their popularity in the early 1990s with artists such as Tupac Shakur, the Notorious B.I.G., Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, and Snoop Dogg at the top of the charts. West Coast rappers such as Tupac Shakur and Snoop Dogg favored gangsta rap, while East Coast rappers, like the Notorious B.I.G. and Sean Combs, stuck to a traditional hip-hop style. The rivalry culminated with the murders of Shakur in 1996 and B.I.G. in 1997.

Along with hip-hop and gangsta rap, alternative rock came to the forefront in the 1990s with grunge. The grunge scene emerged in the mid-1980s in the Seattle area of Washington State. Inspired by hardcore punk and heavy metal, this subgenre of rock was so-called because of its messy, sludgy, distorted guitar sound, the disheveled appearance of its pioneers, and the disaffected nature of the artists. Initially achieving limited success with Seattle band Soundgarden, Seattle independent label Sub Pop became more prominent when it signed another local band, Nirvana. Fronted by vocalist and guitarist Kurt Cobain, Nirvana came to be identified with Generation X—the post–baby boom generation, many of whom came from broken families and experienced violence both on television and in real life. Nirvana’s angst-filled lyrics spoke to many members of Generation X, launching the band into the mainstream. Ironically, Cobain was uncomfortable and miserable, and he would eventually commit suicide in 1994. Nirvana’s success paved the way for other alternative rock bands, including Green Day, Pearl Jam, and Nine Inch Nails. More recently, alternative rock has fragmented into even more specific subgenres.

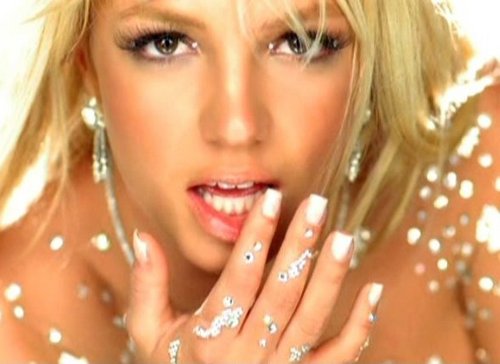

By the end of the 1990s, mainstream tastes leaned toward pop music. A plethora of boy bands, girl bands, and pop starlets emerged, sometimes evolving from gospel choir groups, but more often than not created by talent scouts. The groups were aggressively marketed to teen audiences. Popular bands included the Backstreet Boys, ’N Sync, and the Spice Girls. Meanwhile, individual pop acts from the MTV generation such as Madonna, Michael Jackson, and Prince continued to generate hits.

The 2000s: Pop Stays Strong as Hip-Hop Overtakes Rock in Popularity

The 2000s began right where the 1990s left off, with young singers such as Christina Aguilera and Destiny’s Child ruling the pop charts. Pop music stayed strong throughout the decade with Gwen Stefani, Mariah Carey, Beyoncé, Katy Perry, and Lady Gaga achieving mainstream success. By the end of the decade, country artists, like Carrie Underwood and Taylor Swift, transitioned from country stars to bona fide pop stars. While rock music started the decade strong, by the end of the 2000s, rock’s presence in mainstream music had waned, with a few exceptions such as Nickelback, Linkin Park, and Green Day.

Unlike rock music, hip-hop maintained its popularity, with more commercial, polished artists such as Kanye West, Jay-Z, Lupe Fiasco, and OutKast achieving enormous success. While some gangsta rappers from the 1990s—like Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg—softened their images, other rappers—such as 50 Cent and Eminem—continued to project a tough image and to use violent lyrics. An alternative style of hip-hop emerged in the 2000s that infused positive messages and an element of social conscience to the music that was missing from early hip-hop tracks. Artists such as Common, Mos Def, and the Black Eyed Peas found success even though they didn’t represent traditional stereotypes of hip-hop.

The 2010s: Streaming and Globalization

Your current playlist might begin with Lady Gaga, take a tour to a hit K-Pop band, then land in the productive sounds of a song you found in Roblox by Tobu. Think about the control you have over the playlists you develop. Consider the mixes you make to match the way you feel, for study time, or on road trips, these creations do not box in consumers. All while expressing the moods and emotions tied to our lives. From the 2010s to 2020s, consumers have more control over how music reaches them.

From Post Malone, the Weeknd, Ariana Grande, Adele, and Juice WRLD, to Imagine Dragons, Bastille, Macklemore, Wiz Khalifa, Halsey, and Bruno Mars, the variety of musical styles and artists is evident on the Billboard Decade-End Chart of the 2010s. By breaking away from strict genres to platforms that will suggest a variety of artists and songs, consumers are free to fully explore their interests in the digital realm. Ray Browne’s emphasis on popular culture as a democratic space comes to light through YouTube and SoundCloud providing an avenue for artists creating lo-fi channels, Justin Bieber’s career, and SoundCloud rap. With gatekeepers out of the way and cheaper ways to create music, artists can wield platforms such as YouTube and TikTok to share their music and gather supporters.

In 2018, K-pop band BTS’ Love Yourself: Tear was number one on the Billboard 200 chart. Popular music became a space that crossed cultural and language boundaries to share music world-wide. A playlist no longer has only U.S. hits, but can easily incorporate Latinx, K-pop, Euro-rock, synthwave, and anything else a consumer comes across. Applying Stella Ting-Toomey’s definition of culture here, consider traditions, symbols, norms, values, and beliefs that you have been exposed to through music. Whether you found a new subgenre of rock or a hit from Iceland, you’re experiencing music in a very different way than in decades past.

The Reciprocal Nature of Music and Culture

The tight knit relationship between music and culture is almost impossible to overstate. For example, policies on immigration, war, and the legal system can influence artists and the type of music they create and distribute. Music may then influence cultural perceptions about race, morality, and gender that can, in turn, influence the way people feel about those policies.

The evolution of popular music in the United States in the 20th century was shaped by a myriad of cultural influences. Rapidly shifting demographics brought previously independent cultures into contact and also created new cultures and subcultures, and music evolved to reflect these changes. Among the most important cultural influences on music are migration, the evolution of youth culture, and racial integration.

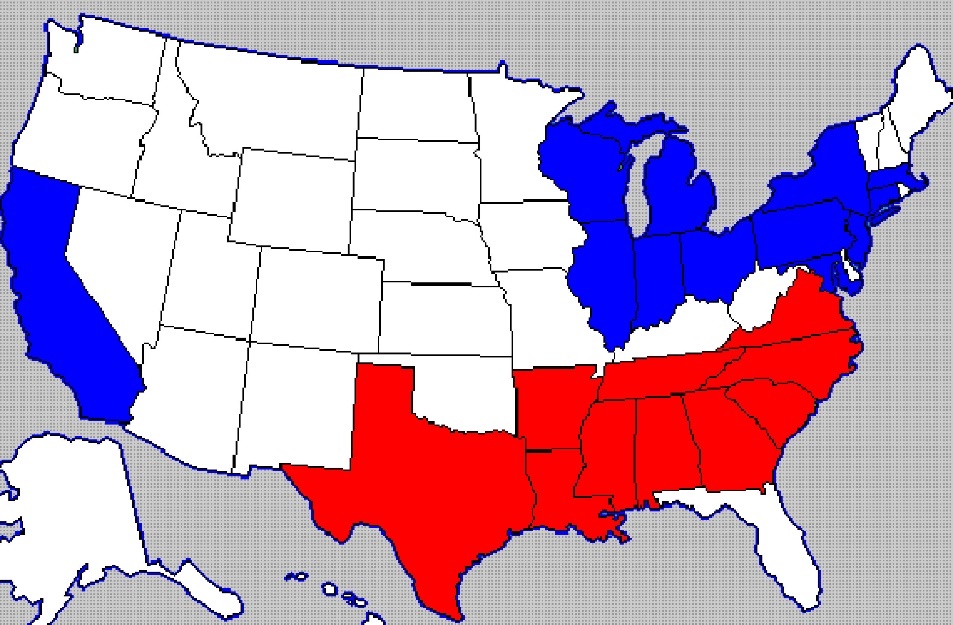

Migration

One of the major cultural influences on the popular music industry over the past century is migration. In 1910, 89 percent of Black Americans still lived in the South, most of them in rural farming areas (Weingroff, 2011). Three years later, a series of disastrous events devastated the cotton industry. World cotton prices plummeted, a boll weevil beetle infestation destroyed large areas of crops, and in 1915, flooding destroyed many of the houses and crops of farmers along the Mississippi River. Already suffering from the restrictive “Jim Crow” laws that segregated schools, restaurants, hotels, and hospitals, Black sharecroppers began to look to the North for a more prosperous lifestyle. Northern states were enjoying an economic boom as a result of an increased demand for industrial goods because of the war in Europe. They were also in need of labor because the war had slowed the rate of foreign immigration to Northern cities. Between 1915 and 1920, as many as 1 million Black individuals moved to Northern cities in search of jobs, closely followed by another million throughout the following decade (Nebraska Studies, 2010). The mass exodus of Black farmers from the South became known as the Great Migration, and by 1960, 75 percent of all Black Americans lived in cities (Emerging Minds, 2005). The Great Migration had a huge impact on political, economic, and cultural life in the North, and popular music reflected this cultural change.

Some of the Black individuals who moved to Northern cities came from the Mississippi Delta, home of the blues. The most popular destination was Chicago. Delta-born pianist Eddie Boyd later told Living Blues magazine, “I thought of coming to Chicago where I could get away from some of that racism and where I would have an opportunity to, well, do something with my talent…. It wasn’t peaches and cream, man, but it was a hell of a lot better than down there where I was born (Szatmary).” At first, the migrants brought their style of country blues to the city. Characterized by the guitar and the harmonica, the Delta blues was identified by its rhythmic structure and strong vocals. Migrant musicians were heavily influenced by Delta blues musicians such as Charley Patton and legendary guitarist Robert Johnson. However, as the urban setting began to influence the migrants’ style, they started to record a hybrid of blues, vaudeville, and swing, including the boogie-woogie and rolling-bass piano. Mississippi-born guitarist Muddy Waters, who moved to Chicago in the early 1940s, revolutionized the blues by combining his Delta roots with an electric guitar and amplifier. He did so partly out of necessity, since he could barely make himself heard in crowded Chicago clubs with an acoustic guitar (Chicago Blues Guitar). Waters’s style was peppier and more buoyant than the sullen country blues. His plugged-in electric blues became the hallmark of the Chicago blues style, influencing countless other musicians and creating the underpinnings of rock and roll. Other migrant bluesmen helped to create regional variations of the blues all around the country, including John Lee Hooker in Detroit, Michigan, and T-Bone Walker in Los Angeles, California.

Youth Culture

Prior to 1945, most music was created with adults in mind, and teenage musical tastes were barely a consideration. Young adults had few freedoms—most males were expected to join the military or get a job to support their fledgling families, while most females were expected to marry young and have children. Few young adults attended college, and personal freedom was limited. Following World War II, this situation changed drastically. A booming economy helped create an American middle class, which created an opening for a youth consumer culture. Unsavory memories of the war discouraged some parents from forcing their children into the military, and many emphasized enjoying life and having a good time. As a result, teenagers found they had a lot more freedom. This new liberalized culture allowed teenagers to make decisions for themselves, and, for the first time, many had the financial means to do so. Whereas many adults enjoyed the traditional sounds of Tin Pan Alley, teens were beginning to listen to rhythm and blues songs played by radio disc jockeys such as Alan Freed. Increased racial integration within the younger generation made them more accepting of Black musicians and their music, which was considered “cool,” and provided a welcome escape from the daunting political and social tension caused by Cold War anxieties. The wide availability of radios, juke boxes, and 45 rpm records exposed this new style of rock and roll music to a broad teenage audience.

Once teenagers had the buying power to influence record sales, record companies began to notice. Between 1950 and 1959, record sales in the United States skyrocketed from $189 million to nearly $600 million (Szatmary). The 45 rpm vinyl records that were introduced in the late 1940s were an affordable option for teens with allowances. Dick Clark, a radio presenter in Philadelphia, soon tuned in to the new teenage tastes. Sensing an opportunity to tap in to a potentially lucrative market, he acquired enough advertising support to turn local hit music telecast Bandstand into a national television phenomenon.

The result was the launch of American Bandstand in 1957, a music TV show that featured a group of teenagers dancing to current hit records. The show’s popularity prompted record producers to create a legion of rock and roll acts specifically designed to appeal to a teenage audience, including Fabian and Frankie Avalon (Grimes, 2011). During its almost 40-year run, American Bandstand was a prominent influence on teenage fashions and musical tastes and, in turn, reflected the contemporary youth culture.

Racial Integration

Following the Great Migration, racial tensions increased in Northern cities. Whereas many Northerners had previously been unconcerned with the issue of race relations in the South, they found themselves confronted with the very real issue of having to compete for jobs with Black migrant workers. Black workers found themselves pushed into undesirable neighborhoods, often living in crowded, unsanitary slums where they were charged exorbitant rates by unscrupulous landlords. During the 1940s, racial tensions boiled over into race riots, most notably in Detroit. The city’s 1943 riot caused the deaths of 34 people, 25 of whom were Black (Gilcrest, 1993).

Frustrated with inequalities in the legal system that distinguished Black and White individuals, members of the civil rights movement pushed for racial equality. In 1948, an executive order granted by President Harry Truman integrated the military. The move toward equality gained further momentum in 1954, with the U.S. Supreme Court decision to end segregation in public schools in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education. The civil rights movement escalated throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, aided by highly publicized events such as Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her seat on a bus to a White passenger in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. In 1964, Congress passed the most sweeping civil rights legislation since the Civil War, forbidding discrimination in public places and authorizing financial aid to enable school desegregation.

Although racist attitudes did not change overnight, the cultural changes brought on by the civil rights movement laid the groundwork for the creation of an integrated society. The Motown sound developed by Berry Gordy Jr. in the 1960s both reflected and furthered this change. Gordy believed that by coaching talented but unpolished Black artists, he could make them acceptable to mainstream culture. He hired a professional to head an in-house finishing school, teaching his acts how to move gracefully, speak politely, and use proper posture (Michigan Rock and Roll Legends). Gordy’s commercial success with gospel-based pop acts such as the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Tops, and Martha and the Vandellas reflected the extent of racial integration in the mainstream music industry. Gordy’s most successful act, the Supremes, achieved 12 No. 1 singles on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

Musical Influences on Culture

Even though pop music is frequently characterized as a negative influence on society, particularly with respect to youth culture, it also has positive effects on culture. Many artists in the 1950s and 1960s pushed the boundaries of socially acceptable behavior with sexually charged movements and androgynous appearances. Without these precedents, acts like the Rolling Stones or David Bowie may have never made the transition into mainstream success.

On the other hand, over the past 50 years, critics have blamed rock and roll for juvenile delinquency, heavy metal for increased teenage aggression, and gangsta rap for a rise in gang warfare among young urban males. One recent study claimed that youths who listen to music with sexually explicit lyrics were more likely to have sex at an early age, stating that exposure to lots of sexually degrading music gives teens “a specific message about sex (MSNBC, 2006).” In addition to its effects on youth culture, popular music has contributed to shifting cultural values regarding race, morality, and gender.

Race

As the music of Chuck Berry and Little Richard gained popularity among White teens in the United States during the 1950s, most of the new rock acts were signed to independent labels, and larger companies such as RCA were losing their share of the market.

To capitalize on the public’s enthusiasm for rock and roll and to prevent the loss of further potential profits, big record companies signed White artists to cover the songs of Black artists. The songs were often censored for the mainstream market by the removal of any lyrics that referenced sex, alcohol, or drugs. Pat Boone was the most successful cover artist of the era, releasing songs originally sung by artists such as Fats Domino, the El Dorados, Little Richard, and Big Joe Turner. Releasing a cover of a Black performer’s song by a White performer was known as hijacking a hit, and this practice usually left black artists signed to independent labels broke. Because large companies such as RCA could widely promote and distribute their records—six of Boone’s recordings reached the No. 1 spot on the Billboard chart—their records frequently outsold the original versions. Many White artists and producers would also take writing credit for the songs they covered and would buy the rights to songs from Black writers without giving them royalties or songwriting credit. This practice fueled racism within the music industry. Independent record producer Danny Kessler of Okeh Records said, “The odds for a black record to crack through were slim. If the black record began to happen, the chances were that a white artist would cover—and the big stations would play the white records…. There was a color line, and it wasn’t easy to cross (Szatmary).”

Although cover artists profited from the work of Black R&B singers, occasionally they also helped to promote the original recordings. Many teenagers who heard covers on mainstream radio stations sought out the original artists’ versions, increasing sales and prompting Little Richard to refer to Pat Boone as “the man who made me a millionaire (Crane, 2005).” Benefiting from covers also worked both ways. In 1962, soul singer Ray Charles covered Don Gibson’s hit “I Just Can’t Stop Loving You,” which became a hit on country and western charts and furthered mainstream acceptance of Black musicians. Other Black artists to cover hits by White performers included Otis Redding, who performed the Rolling Stones hit “Satisfaction,” and Jimi Hendrix, who covered Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower.”

Hijacking Hits

Releasing cover versions of hit songs was fairly standard practice before the 1950s because it was advantageous for songwriters and producers to have as many artists as possible sing their records to maximize royalties. Several versions of the same song often appeared in the music charts at the same time. However, the practice acquired racial connotations during the 1950s when larger music labels hijacked R&B hits, using their financial strength to promote the cover version at the expense of the original recording, which often exploited Black talent. As a result, many 1950s R&B artists lost out on royalties.

Two contemporary Black performers who were victims of this practice were R&B singer LaVern Baker and blues singer Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. Baker, who was signed with then small-time label Atlantic Records, had been promoted as a pop singer. Because her songs appealed to mainstream audiences, they were ideal for covering, and industry giant Mercury Records took full advantage of this. When Baker released her 1955 hit “Tweedle Dee,” Mercury immediately put out its own version, a note-for-note cover sung by White pop singer Georgia Gibbs. Atlantic could not match Mercury’s marketing budget, and Gibbs’s version outsold Baker’s recording, causing her to lose an estimated $15,000 in royalties (Parales, 1997).

Around the same time, Arthur Crudup was producing hits such as “So Glad You’re Mine,” “Who’s Been Foolin’ You,” “That’s All Right Mama,” and “My Baby Left Me,” which were subsequently released by performers such as Elvis Presley, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Rod Stewart for huge financial gain, Crudup’s songs made everybody rich—except him. This realization caused him to quit playing altogether in the late 1950s. A later attempt to collect back royalties was unsuccessful (Stanton, 1998). Baker filed a lawsuit in an attempt to revise the Copyright Act of 1909, making it illegal to copy an arrangement verbatim without permission. The lawsuit was unsuccessful, and Gibbs continued to cover Baker’s songs (Dahl)

Morality

When Elvis Presley burst onto the rock and roll scene in the mid-1950s, many conservative parents of teenagers all over the United States were horrified. With his gyrating hips and sexually suggestive body movements, Presley was viewed as a threat to the moral well-being of young women. Television critics denounced his performances as vulgar, and on a 1956 appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, cameras filmed him only from the waist up. One critic for the New York Daily News wrote that popular music “has reached its lowest depths in the ‘grunt and groin’ antics of one Elvis Presley (Collins, 2002).” Despite the critics’ opinions, Presley immediately gained a fan base among teenage audiences, particularly adolescent girls, who frequently broke into hysterics at his concerts. Rather than tone down his act, Presley defended his movements as manifestations of the music’s rhythm and beat and continued to gyrate on stage. Liberated from the constraints imposed by morality watchdogs, Presley set a precedent for future rock and roll performers and marked a major transition in popular culture.

In addition to decrying raunchy onstage performances by rock and roll artists, moralists in the conservative Eisenhower era objected to the sexually suggestive lyrics found in original rock and roll songs. Big Joe Turner’s version of “Shake, Rattle, and Roll” used sexual phrases and referred to the bedroom, while Little Richard’s original version of “Tutti Frutti” contained the phrase “tutti frutti, loose booty (Hall & Hall, 2006).” Although many of these lyrics were sanitized for mainstream White audiences when they were rereleased as cover versions, the idea that rock and roll was a threat to morality had been firmly implanted in many people’s minds.

Ironically, many of the controversial key figures in the rock and roll era came from extremely religious backgrounds. Presley was a member of the evangelical First Assembly of God Church, where he acquired his love of gospel music (History Of Rock). Similarly, Ray Charles soaked up gospel influences from his local Baptist church (Walk Of Fame). Jerry Lee Lewis came from a strict Christian background and often struggled to reconcile his religious beliefs with the moral implications of the music he created. During a recording session in 1957, Lewis argued with manager Sam Phillips that the hit song “Great Balls of Fire” was too “sinful” for him to record (History, 1957). The religious backgrounds of the rock and roll pioneers both influenced and challenged moral norms. When Ray Charles recorded “I Got a Woman” in 1955, he reworded the gospel tune “Jesus Is All the World to Me,” drawing criticism that the song was sacrilegious. Despite the objections, Charles’s style caught on with other musicians, and his experimentation with merging gospel and R&B resulted in the birth of soul music.

Gender

While Presley was revolutionizing people’s notions of sexual freedom and expression, other performers were changing cultural norms regarding gender identity. Dressed in flamboyant clothing with a pompadour hairstyle and makeup, Little Richard was an exotic, androgynous performer who blurred traditional gender boundaries and shocked 1950s audiences with his blatant campiness. Between his wild onstage antics, bisexual tendencies, and love of post-concert orgies, the self-proclaimed “King and Queen of Rock and Roll” challenged many social conventions of the time (Buckley, 2003). Little Richard’s flamboyant, gender-bending appearance was so outrageous that it was not taken seriously during the 1950s—he was considered an entertainer whose androgynous look bore no relevance to the real world. However, Richard paved the way for future entertainers to shift cultural perceptions of gender. Later musicians such as David Bowie, Prince, and Boy George adopted his outrageous style, frequently appearing on stage wearing glittery costumes and heavy makeup. The popularity of these 1970s and 1980s pop idols, along with other gender-bending performers such as Annie Lennox and Michael Jackson, helped make androgyny more acceptable in mainstream society.