4 Film and Bricolage

“Walt Whitman once said, ‘I see great things in baseball. It’s our game, the American game. It will repair our losses and be a blessing to us.’ You could look it up.” — Annie Savoy, played by Susan Sarandon, from the film Bull Durham

More than Merely Movies

The LA Times looked up the reference quoted at the end of the film Bull Durham and found that Whitman’s sentiments were represented more or less accurately. What appears in the film is a distillation of a longer paraphrase—made by Horace L. Traubel, a noted Whitman biographer—of a statement that Whitman probably did make. The line in Bull Durham captures the essence of the quote, even if it is a paraphrase of a paraphrase. This is often what great films do. They take what is available in reality and distill it down so viewers can understand it the first time. When you make a copy of a copy, things get blurry and more difficult to decipher. Films often do the exact opposite with elements of culture. They reduce present reality and essential past experiences into distilled intertextual products—mediated messages that combine various types of text into one.

A movie combines moving pictures (video, film or animation), sound, graphics, special effects and, of course, written text, which is most often spoken as dialogue. It can be delivered as a disembodied voice speaking over video in what is called a voice-over, or text can appear in graphic form as actual text on screen. Each element from video to sound to graphics and special effects is considered a text. The various texts are sewn together in a multi-layered story.

Movies are popular because of the stories they tell and the way they tell them. The most popular films have a compelling narrative, fantastic special effects, great cinematography, supportive, realistic sound effects and often a great score. Compiling and combining texts for mass audiences in major motion pictures is incredibly difficult to do well, but with digital technology, many millions of people can create intertextual stories on their own.

Whether you are a YouTube producer or enjoy making social media stories every day, you can be an intertextual storyteller with tools readily available on the mass market. The “readily available” part calls to mind the concept of bricolage, which in intertextual storytelling means taking the images, sounds, and words readily available to you, along with the recording and editing tools that are also available, and making stories intended for others to appreciate.This chapter covers the film industry and bricolage together to emphasize that all mediated messages, whether they are an individual’s latest Instagram production or a major motion picture studio’s latest multimillion-dollar gamble, are exercises in bricolage.

This chapter first discusses film as an industry and as a modern mass media platform. It goes on to examine the potential cultural influence of filmmaking and the implications of this potential for filmmakers. The chapter unpacks the concept of bricolage in the context of filmmaking. Finally, this chapter considers the role of passion in crafting messages for mass media audiences.

Filmmakers are some of the most passionate, creative people in the mass media industry. They balance knowledge and skill in managing many types of media production. At their best, they are enthusiastic about storytelling and about professionally mastering many aspects of the art form. At their worst, filmmakers (including producers, directors and others in the industry) are controlling manipulators who apply their efforts recklessly and for personal gain. There is a reason some of the worst outrages leading to the Me Too movement happened in the film industry. It is an industry where powerful people, usually men, have for too long used their power to do awful things without repercussions. This issue will be addressed before the chapter’s conclusion.

A Brief History of Film

This section draws heavily from a text called Movie-Made America by Robert Sklar who points out that popular films in America were the first modern mass medium. Since this text considers the penny press the first mass medium, it will be necessary to clarify. The penny press arose around the end of the First Industrial Revolution. By the 1830s, many people in newly-developing nations had left the agrarian life and moved to cities to work for wages in some form of manufacturing. The penny press was identified as their mass medium because large numbers of people consumed the same newspapers at an affordable cost. They shared collective narratives about what was happening in the world that editors considered important. (Readers were privy to the agenda-setting function of the mass media; however, the penny press was often a regional mass medium. Different city, different paper.)

Fifty years later, the Second Industrial Revolution progressed with advancements in the textile, steel, automotive and war industries, which continued through World War I and World War II. Sklar argues this industrialization made the film industry viable. After working 10- or 12-hour days to keep up with demand and to make enough money to survive and perhaps thrive, people were looking for quick, easy and relatively affordable entertainment. Motion pictures shown on big screens in theaters built for sizable audiences fit the bill.

What made filmmaking a mass media industry was the ability to show the same film to large audiences again and again. Films also presented a new way of telling stories. Early filmmakers experimented with the art form and actively sought to make their work different from anything that had come before. In art and culture, a purposeful break from the past is one way of defining modernity. Thus, film was the first modern mass medium. The very first movie parlors, however, were not capable of projecting film.

Early Moviegoing

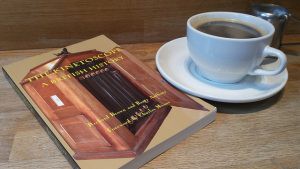

According to Sklar, when the film industry arose at the turn of the 20th century, films were first exhibited as short motion pictures viewed in kinetoscopes. In the image of the kinetoscope shown in this chapter on a book’s cover, you can see an open cabinet. Inside the cabinet is a long, winding film. To watch a movie, you would lean over the top of the closed cabinet and peer into the viewfinder. It cost a nickel. Most often, immigrants and working-class people frequented nickelodeons, which is what the parlors and theaters housing kinetoscopes were called. In the United States, film brought American culture to immigrants and immigrant culture to other Americans in an exchange that helped foster social change.

The Developing Movie Industry

Nickelodeons were not profitable enough to sustain the industry in the long term. Recognizing that showing films was more profitable when movies were projected for many viewers at the same time, filmmakers rushed to create films that looked best in that format. When film was taken out of the box and projected on large screens, it opened up the medium to become the mass market industry it is today. From the perspective of theater owners, it was better to show one film from one protected projection machine to an audience of paying customers than to have people fill up a parlor and wait in line to climb on top of the equipment one at a time. As film became a mass medium, concerns over content and the medium’s potential to influence public opinion grew.

Movie Ratings

In the 20th century, producers quickly learned that motion pictures could be the most powerful propaganda tool in the world. By bringing modern messages to mass audiences, films were (and still are) able to shape public opinion through culture. Their reach extends beyond influencing trends: Films are massively popular emotional and educational cultural products that can influence the shape and direction of social structures.

Early on, messages in the medium were not subject to government or church approval, which concerned the leaders of these institutions. The battle for control over the industry has never stopped. The current rating system used in the United States is a voluntary system. That is, the government does not censor films. The industry regulates and censors itself through the maintenance of a movie ratings system, which is not without controversy.

Because films can have massive economic, cultural and social impacts, it should always be expected that powerful groups will try to exert their influence over this medium.

Movies and Culture

There are dozens of journals that examine the relationships between film and culture. Films influence popular culture, group culture and just about everyone’s personal culture. If your professor or instructor were to name an abstract emotion, a major industry, or a popular sport, you could probably think of a film that deals with that aspect of culture or society. Think about gender norms, religious sensibilities, economic inequality, gay rights, militarism, environmentalism, family values, popular history, patriotism, cultural violence, liberty, race, global technology, artificial intelligence, or sheep farming. There is a movie for almost every group culture. Social issues often drive filmmakers, but they may also pursue stories about popular issues to attract the broadest possible audience. Filmmakers often balance the desire to highlight the social and cultural issues they care about with the need to make money in a global cultural industry.

Filmmaking Practice

The American film industry employs more than 2 million people, according to the Motion Picture Association of America. Filmmakers and studios are protected by the First Amendment to discuss almost any topic they choose. The marketplace is often a more limiting factor than other forms of social or cultural influence. Many great stories are not made into films because it is too costly to produce a major motion picture to risk box-office losses. It is the right of the film studio to pursue profits, but many filmmakers consider their work a vocation or calling. The driving artistic and economic forces often compete wherever movies are made.

Filmmakers today gain experience by making commercials, music videos, television shows, independent movies, and even web series posted directly online. Young filmmakers rarely work with actual film. It is far more expensive to shoot film than video. The most common format at the time this book is being revised is SD (secure digital) media. The file type and codec depends on the camera. Many filmmakers shoot video on DSLR cameras and enjoy the ability to switch lenses for different conditions or effects. This type of media can store large files (think 2 to a theoretical max of 128 terabytes of storage). As video quality increases, so does the need for greater storage capacity. Video formats such as 4K and 8K are known as ultra-high definition (UHD). They enable filmmakers to capture and show incredibly detailed images.

Successful filmmakers not only have to know the tools of the trade, but they must also be good at networking. Films may cost up to a billion dollars to make and to promote. Filmmakers must demonstrate they can work well with others before a studio will take such a large chance on their talent. Because so much social and cultural influence and financial risk rest on a few flagship films each year, the controls are generally only given to proven filmmakers. To truly represent the voices of women, minorities, immigrants and other cultural groups in our society, there need to be pathways in the industry to producing, directing and promoting major films. For example, even before news broke about the many women who have been sexually assaulted in the industry, Hollywood had drawn mass attention for problems with industry sexism. Perhaps for the industry to be a better place for women personally, it needs to be a better place professionally. For this reason, there must be a variety of industry entry points if Hollywood is truly going to offer diverse points of view told from diverse groups of people. An entry point is a position in an industry that an individual can use to gain the experience needed to move up the career ladder. All of the technical skill in the world is of little use if there are not pathways to powerful positions.

Storytelling

Filmmaking tools and practical career preparations give options and opportunities to professionals, but they do not make films better by themselves. In other words, a technically skilled filmmaker might still fail because the industry is about storytelling. You might like a film with great special effects more than you like one without any, but the development of a new special effects technology does not make every film that employs it a good one. You can probably think of a bad movie with relatively good special effects (Spoiler alert: Lots of Michael Bay). Likewise, there are great classic films with almost no special effects. The tools are only as good as the people wielding them.

As suggested, films can play an important social and cultural role. They can communicate political agendas and can push issues to the forefront of media attention. Filmmakers and studies, on the other hand, may also go out of their way not to make political statements. Whether a film communicates directly or, more subtly, the most successful films combine great technical skill with a combination of trusted and innovative storytelling techniques.

A key goal of movie marketing is to make people anticipate a film so much that they feel they have to see it on the opening weekend for fear of missing out. For people who do not often go to movies, one key indicator they use to judge a film’s success is its rank at the box office. It takes the support of both regular movie fans and those who only see a few films a year for a movie to be a true blockbuster. The best and most successful films combine great technical prowess with innovative but approachable storytelling. The best filmmakers have to be able to get professional work out of hundreds or even thousands of people working on a single project. They must be able to manage actors, special effects crew members, film crews, and marketing professionals, to name a few. Filmmakers must also have a sense of the interplay between texts. The best storytelling is multifaceted and emotional but sufficiently connected to reality to be relatable.

Bricolage

Every motion picture that succeeds at being intertextual — that is, every film that combines a variety of types of text into a tapestry for audiences with a good story behind it — is a matter of bricolage. The term “bricolage” is related to the French word for “tinkering” and calls to mind the word “collage.” Perhaps you’ve made several collages in school with the idea being to create art or to depict a concept using available materials rather than drawing or painting something from scratch using a single medium. Bricolage refers to a do-it-yourself tinkering process where you make something new out of other things.

You might argue that new films are made with new technology, not existing film clips or video files. You might also point out that special effects, 3D projection, and IMAX technology are not cheap, and the materials to make modern blockbusters are not going to be found simply lying around. You would be correct if movies were only storage media they are shot on, the computers they are edited in, and the 3D glasses you wear in the theater. But in reality, every film is made with limited resources using the existing tools and the talent available at the time. Every film is, to some extent, a pastiche, a reference to the films that came before. Bricolage is about taking the tools, materials, and talents available to you, tinkering with them, and making something different that has its own meaning. Think about making dinner from leftovers. Turkey and Swiss cheese with pancakes for bread? Why not? Throw some chili on it. Wash it down with a light beer. Bricolage.

Some bricolage is better than others. Major motion picture filmmakers do a kind of bricolage. They simply have more expensive tools. Often, it is said, films are written three times. First, the script is written. Then the film is shot and brought to life by the director, actors, film crews and effects crews. Finally, a film is rewritten in editing. This notion that films are written as scripts, revised in the shooting process and written a third time in the editing booth comes from this video summarizing how the original Star Wars was saved in editing. Filmmaking is a collaborative, iterative process, which means it may take many people many tries to create a successful story.

The Limits of Passion

Some individuals will be impressed by Quentin Tarantino’s assertion, “I didn’t go to film school. I went to films.” It is tempting to think that all you need to know about filmmaking can be learned by watching films. That is certainly the start of developing a passion that can drive a career, but there is a case to be made for a formal education.

College is where you learn how to think strategically. You learn how to work with other professionals-in-training. Working through college for four years or more, you gain stability and personal connections. You may not all end up as filmmakers or mass media professionals, but the critical thinking and problem-solving skills you learn from a liberal arts background prepare you to evaluate sources of information. You learn how to ask where people selling you a story got their information. If you learn how to learn, how to analyze media critically and how to make your own work as professional as possible, you will be prepared for shifts in the industry that might otherwise sap your passion.

Passion is like a pit bull. It can be a friend, companion, and protector — something to rely on when times are tough. Passion that is mistreated, ignored, or that knows only about the darker, more violent side of life, can get out of its owner’s control. There is no specific, perfect formula for cultivating your passion. Choose one and apply it in every college course you possibly can. If your education works for you, your passion can be tamed and it will always with you.

Before he was known as a screenwriter and before he had directed anything, Quentin Tarantino was doing more than just watching movies. He worked with people who made films. His work at a production company enabled him to get his script for True Romance to film director Tony Scott. Without his production company experience, no one would have cared that he knew everything there was to know about kung fu movies and westerns. He would have been a very knowledgeable video store clerk in a world where video stores were about to die.

So Wrong for so Long

When Uma Thurman talked about Harvey Weinstein’s attempts to sexually assault her, she told a story dozens of other women shared about Weinstein’s abusive, criminal behavior. The prevalence of sexual assault in Hollywood was a driving force behind the global Me Too movement of women as well as men sharing stories of sexual assault and abuse. Abusive behavior, mostly on the part of men in the workplace, has been tolerated in Hollywood and in other corporate and institutional cultures for far too long. Sometimes it was even joked about. Most often, it was allowed to be part of the business of entertainment.

In a better future for film and other forms of media making, sexual assault would not be tolerated, and people of all genders and backgrounds would support each other against those who abuse their power to reinforce their dominance and for sexual gratification. Laws did not do enough to protect women from predators, but speaking out has started to make a difference in a culture that has tolerated harassment, abuse, and rape. For the film industry to truly be one of free expression and thoughtful cultural and social meaning-making, it cannot be a place where more than half of society is objectified and dehumanized regularly.

Uma Thurman also noted in her opinion article about Harvey Weinstein that she was objectified to the point that Quentin Tarantino pushed her to risk her life when shooting a car chase scene. Her story was about sexual objectification and assault but also about the way men, in particular, devalue women in many aspects of life. If Hollywood can change, its stories change too and the social and cultural impacts of that movement would be felt like waves emanating from this time for future generations.

Movies Mirror Culture

The relationship between movies and culture involves a complicated dynamic. While American movies certainly influence the mass culture that consumes them, they are also an integral part of that culture, a product of it, and therefore a reflection of prevailing concerns, attitudes, and beliefs. In considering the relationship between film and culture, it is important to keep in mind that, while certain ideologies may be prevalent in a given era, not only is American culture as diverse as the populations that form it, but it is also constantly changing from one period to the next. Mainstream films produced in the late 1940s and into the 1950s, for example, reflected the conservatism that dominated the sociopolitical arenas of the time. However, by the 1960s, a reactionary youth culture began to emerge in opposition to the dominant institutions, and these anti-establishment views soon found their way onto the screen—a far cry from the attitudes most commonly represented only a few years earlier.

In one sense, movies could be characterized as America’s storytellers. Not only do Hollywood films reflect certain commonly held attitudes and beliefs about what it means to be American, but they also portray contemporary trends, issues, and events, serving as records of the eras in which they were produced. Consider, for example, films about the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks: Fahrenheit 9/11, World Trade Center, United 93, and others. These films grew out of a seminal event of the time, one that preoccupied the consciousness of Americans for years after it occurred.

Birth of a Nation

In 1915, director D. W. Griffith established his reputation with the highly successful (and extremely racist) film The Birth of a Nation, based on Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansman, a pro-segregation narrative about the American South during and after the Civil War. At the time, The Birth of a Nation was the longest feature film ever made, at almost 3 hours, and contained huge battle scenes that amazed and delighted white audiences. Griffith’s storytelling ability helped solidify the narrative style that would go on to dominate feature films. He also experimented with existing editing techniques such as close-ups, jump cuts, and parallel editing that helped make the film an artistic achievement. In the past, filmmaking classes praised Griffith for these filmmaking techniques, that had already been introduced and used by other innovative filmmakers (see Alice Guy or the short silent film “The Sick Kitten”).

Griffith’s film found success largely because it captured the social and cultural tensions of the era. As American studies specialist Lary May has argued, “[Griffith’s] films dramatized every major concern of the day (May, 1997).” In the early 20th century, fears about recent waves of immigrants had led to certain racist attitudes in mass culture, with “scientific” theories of the time purporting to link race with inborn traits like intelligence and other capabilities. Additionally, the dominant political climate, largely a reaction against populist labor movements, was one of conservative elitism, eager to attribute social inequalities to natural human differences (Darity). According to a report by the New York Evening Post after the film’s release, even some Northern audiences “clapped when the masked riders took vengeance on Negroes (Higham).” However, the outrage many groups expressed about the film is a good reminder that American culture is not monolithic, that there are always strong contingents in opposition to dominant ideologies.

While critics praised the film for its narrative complexity and epic scope, many others were outraged and even started riots at several screenings because of its highly controversial, openly racist attitudes, which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and blamed Southern Blacks for the destruction of the war (Higham). Many Americans joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in denouncing the film, and the National Board of Review eventually cut a number of the film’s racist sections (May). However, it’s important to keep in mind the attitudes of the early 1900s. At the time the nation was divided, and Jim Crow laws and segregation were enforced. Nonetheless, The Birth of a Nation was the highest grossing movie of its era. In 1992, the film was classified by the Library of Congress among the “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant films” in U.S. history.

“The American Way”

Until the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, American films after World War I generally reflected the neutral, isolationist stance that prevailed in politics and culture. However, after the United States was drawn into the war in Europe, the government enlisted Hollywood to help with the war effort, opening the federal Bureau of Motion Picture Affairs in Los Angeles. Bureau officials served in an advisory capacity on the production of war-related films, an effort with which the studios cooperated. As a result, films tended toward the patriotic and were produced to inspire feelings of pride and confidence in being American and to clearly establish that America and its allies were forces of good. For instance, critically acclaimed Casablanca paints a picture of the ill effects of fascism, illustrates the values that heroes like Victor Laszlo hold, and depicts America as a place for refugees to find democracy and freedom (Digital History).

These early World War II films were sometimes overtly propagandist, intended to influence American attitudes rather than present a genuine reflection of American sentiments toward the war. Frank Capra’s Why We Fight films, for example, the first of which was produced in 1942, were developed for the U.S. Army and were later shown to general audiences; they delivered a war message through narrative (Koppes & Black, 1987). As the war continued, however, filmmakers opted to forego patriotic themes for a more serious reflection of American sentiments, as exemplified by films like Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat.

Youth versus Age: From Counterculture to Mass Culture

In Mike Nichols’s 1967 film The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman, as the film’s protagonist, enters into a romantic affair with the wife of his father’s business partner. However, Mrs. Robinson and the other adults in the film fail to understand the young, alienated hero, who eventually rebels against them. The Graduate, which brought in more than $44 million at the box office, reflected the attitudes of many members of a young generation growing increasingly dissatisfied with what they perceived to be the repressive social codes established by their more conservative elders (Dirks).

This baby boomer generation came of age during the Korean and Vietnam wars. Not only did the youth culture express a cynicism toward the patriotic, prowar stance of their World War II–era elders, but they displayed a fierce resistance toward institutional authority in general, an antiestablishmentism epitomized in the 1967 hit film Bonnie and Clyde. In the film, a young, outlaw couple sets out on a cross-country bank-robbing spree until they’re killed in a violent police ambush at the film’s close (Belton).

Bonnie and Clyde’s violence provides one example of the ways films at the time were testing the limits of permissible on-screen material. The youth culture’s liberal attitudes toward formally taboo subjects like sexuality and drugs began to emerge in film during the late 1960s. Like Bonnie and Clyde, Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 Western The Wild Bunch, displays an early example of aestheticized violence in film. The wildly popular Easy Rider (1969)—containing drugs, sex, and violence—may owe a good deal of its initial success to liberalized audiences. And in the same year, Midnight Cowboy, one of the first Hollywood films to receive an X rating (in this case for its sexual content), won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture (Belton). As the release and subsequently successful reception of these films attest, what at the decade’s outset had been countercultural had, by the decade’s close, become mainstream.

The Hollywood Production Code

When the MPAA (originally MPPDA) first banded together in 1922 to combat government censorship and to promote artistic freedom, the association attempted a system of self-regulation. However, by 1930—in part because of the transition to talking pictures—renewed criticism and calls for censorship from conservative groups made it clear to the MPPDA that the loose system of self-regulation was not enough protection. As a result, the MPPDA instituted the Production Code, or Hays Code (after MPPDA director William H. Hays), which remained in place until 1967. The code, which according to motion picture producers concerned itself with ensuring that movies were “directly responsible for spiritual or moral progress, for higher types of social life, and for much correct thinking (History Matters),” was strictly enforced starting in 1934, putting an end to most public complaints. However, many people in Hollywood resented its restrictiveness. After a series of Supreme Court cases in the 1950s regarding the code’s restrictions to freedom of speech, the Production Code grew weaker until it was finally replaced in 1967 with the MPAA rating system (American Decades Primary Sources, 2004).

MPAA (MPA) Ratings

films like Bonnie and Clyde and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) tested the limits on violence and language, it became clear that the Production Code was in need of replacement. In 1968, the MPAA adopted a ratings system to identify films in terms of potentially objectionable content. By providing officially designated categories for films that would not have passed Production Code standards of the past, the MPAA opened a way for films to deal openly with mature content. The ratings system originally included four categories: G (suitable for general audiences), M (equivalent to the PG rating of today), R (restricted to adults over age 16), and X (equivalent to today’s NC-17).

The MPAA rating systems, with some modifications, is still in place today. Before release in theaters, films are submitted to the MPAA board for a screening, during which advisers decide on the most appropriate rating based on the film’s content. However, studios are not required to have the MPAA screen releases ahead of time—some studios release films without the MPAA rating at all. Commercially, less restrictive ratings are generally more beneficial, particularly in the case of adult-themed films that have the potential to earn the most restrictive rating, the NC-17. Some movie theaters will not screen a movie that is rated NC-17. When filmmakers get a more restrictive rating than they were hoping for, they may resubmit the film for review after editing out objectionable scenes (Dick, 2006).

The New War Film: Cynicism and Anxiety

Unlike the patriotic war films of the World War II era, many of the films about U.S. involvement in Vietnam reflected strong antiwar sentiment, criticizing American political policy and portraying war’s damaging effects on those who survived it. Films like Dr. Strangelove (1964), M*A*S*H (1970), The Deer Hunter (1978), and Apocalypse Now (1979) portray the military establishment in a negative light and dissolve clear-cut distinctions, such as the “us versus them” mentality, of earlier war films. These, and the dozens of Vietnam War films that were produced in the 1970s and 1980s—Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986) and Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), for example—reflect the sense of defeat and lack of closure Americans felt after the Vietnam War and the emotional and psychological scars it left on the nation’s psyche (Dirks, 2010; Anderegg, 1991). A spate of military and politically themed films emerged during the 1980s as America recovered from defeat in Vietnam, while at the same time facing anxieties about the ongoing Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Fears about the possibility of nuclear war were very real during the 1980s, and some film critics argue that these anxieties were reflected not only in overtly political films of the time but also in the popularity of horror films, like Halloween and Friday the 13th, which feature a mysterious and unkillable monster, and in the popularity of the fantastic in films like E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Star Wars, which offer imaginative escapes (Wood, 1986).

Movies Shape Culture

Just as movies reflect the anxieties, beliefs, and values of the cultures that produce them, they also help to shape and solidify a culture’s beliefs. Sometimes the influence is trivial, as in the case of fashion trends or figures of speech. After the release of Flashdance in 1983, for instance, torn T-shirts and leg warmers became hallmarks of the fashion of the 1980s (Pemberton-Sikes, 2006). However, sometimes the impact can be profound, leading to social or political reform, or the shaping of ideologies.

Film and the Rise of Mass Culture

During the 1890s and up until about 1920, American culture experienced a period of rapid industrialization. As people moved from farms to centers of industrial production, urban areas began to hold larger and larger concentrations of the population. At the same time, film and other methods of mass communication (advertising and radio) developed, whose messages concerning tastes, desires, customs, speech, and behavior spread from these population centers to outlying areas across the country. The effect of early mass-communication media was to wear away regional differences and create a more homogenized, standardized culture.

Film played a key role in this development, as viewers began to imitate the speech, dress, and behavior of their common heroes on the silver screen (Mintz, 2007). In 1911, the Vitagraph company began publishing The Motion Picture Magazine, America’s first fan magazine. Originally conceived as a marketing tool to keep audiences interested in Vitagraph’s pictures and major actors, The Motion Picture Magazine helped create the concept of the film star in the American imagination. Fans became obsessed with the off-screen lives of their favorite celebrities, like Pearl White, Florence Lawrence, and Mary Pickford (Doyle, 2008).

American Myths and Traditions

American identity in mass society is built around certain commonly held beliefs, or myths about shared experiences, and these American myths are often disseminated through or reinforced by film. One example of a popular American myth, one that dates back to the writings of Thomas Jefferson and other founders, is an emphasis on individualism—a celebration of the common man or woman as a hero or reformer. With the rise of mass culture, the myth of the individual became increasingly appealing because it provided people with a sense of autonomy and individuality in the face of an increasingly homogenized culture. The hero myth finds embodiment in the Western, a film genre that was popular from the silent era through the 1960s, in which the lone cowboy, a seminomadic wanderer, makes his way in a lawless, and often dangerous, frontier. An example is 1952’s High Noon. From 1926 until 1967, Westerns accounted for nearly a quarter of all films produced. In other films, like Frank Capra’s 1946 movie It’s a Wonderful Life, the individual triumphs by standing up to injustice, reinforcing the belief that one person can make a difference in the world (Belton). And in more recent films, hero figures such as Indiana Jones, Luke Skywalker (Star Wars), and Neo (The Matrix) have continued to emphasize individualism.

Social Issues in Film

In Helen O’Hara’s 2022 book Women vs. Hollywood: The Rise of Women in Film, O’Hara outlines the early women pioneers of film. Filmmakers such as Lori Weber, one of the most powerful and successful female directors of the silent era, wielded film to address social issues such as gossip, sexual assault, poverty, abortion, and birth control (O’Hara, 2022). Since these early days, filmmakers have been producing movies that address social issues, sometimes subtly, and sometimes very directly. Films like Hotel Rwanda (2004), about the 1994 Rwandan genocide, or The Kite Runner (2007), a story that takes place in the midst of a war-torn Afghanistan, have captured audience imaginations by telling stories that raise social awareness about world events. The comedy/drama sci-fi film Don’t Look Up (2021), explores disinformation and media as two astronomers attempt to warn humanity about a planet-destroying comet. A number of documentary films directed at social issues have had a strong influence on cultural attitudes and have brought about significant change.

In the 2000s, documentaries, particularly those of an activist nature, were met with greater interest than ever before. Films like Super Size Me (2004), which documents the effects of excessive fast-food consumption and criticizes the fast-food industry for promoting unhealthy eating habits for profit, and Food, Inc. (2009), which examines corporate farming practices and points to the negative impact these practices can have on human health and the environment, have brought about important changes in American food culture (Severson, 2009). Just 6 weeks after the release of Super Size Me, McDonald’s took the supersize option off its menu and since 2004 has introduced a number of healthy food options in its restaurants (Sood, 2004). Other fast-food chains have made similar changes (Sood, 2004).

Other documentaries intended to influence cultural attitudes and inspire change include those made by director Michael Moore. Moore’s films present a liberal stance on social and political issues such as health care, globalization, and gun control. His 2002 film Bowling for Columbine, for example, addressed the Columbine High School shootings of 1999, presenting a critical examination of American gun culture. While some critics have accused Moore of producing propagandistic material under the label of documentary because of his films’ strong biases, his films have been popular with audiences, with four of his documentaries ranking among the highest grossing documentaries of all time. Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), which criticized the second Bush administration and its involvement in the Iraq War, earned $119 million at the box office, making it the most successful documentary of all time (Dirks, 2006).

Mediated messages that combine various types of text into one. Texts are broadly defined here to include video, audio, animated, graphic and other forms of textual information.

Voiced information edited to accompany video such that the audio overrides the sound of the original video. Voice-overs can complement the video but do not necessarily reference it directly. As an editing technique, using voice-over is common in entertainment and video news production.

In the context of the praxis of digital culture, it means to “do it yourself,” or to make a creative work on any media platform of your choosing using available tools and content. From the French and related to another French word, “collage.”

In reference to art and other forms of cultural production, a purposeful break from the past.

A parlor or theater housing kinetoscopes, which were early machines used for viewing motion pictures. So named because kinetoscopes usually cost a nickel to play. Nickel + odeon, which itself is a classical term (Greek and Roman) for a building dedicated to singing or poetry productions.

A position in an industry that an individual can use to gain the experience needed to move up the career ladder.