The cost of money is the opportunity cost of holding money instead of investing it, depending on the rate of interest.

Learning Objectives

Explain the sources of the cost of money

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The concept of the cost of money has its basis, as does the subject of finance in general, in the time value of money.

- The time value of money refers to the fact that a dollar in hand today is worth more than a dollar promised at some future time.

- The trade-off between money now (holding money) and money later (investing) depends on, among other things, the rate of interest you can earn by investing. Therefore, interest is the cost of money.

Key Terms

- Opportunity cost: The cost of an opportunity forgone (and the loss of the benefits that could be received from that opportunity); the most valuable forgone alternative.

- interest rate: The percentage of an amount of money charged for its use per some period of time. It can also be thought of as the cost of not having money for one period, or the amount paid on an investment per year.

The concept of the cost of money has its basis, as does the subject of finance in general, in the time value of money. The time value of money is the value of money, taking into consideration the interest earned over a given amount of time. If offered a choice between $100 today or $100 in a year’s time – and there is a positive real interest rate throughout the year – a rational person will choose $100 today. This is described by economists as time preference. Time preference can be measured by auctioning off a risk free security–like a US Treasury bill. If a $100 note, payable in one year, sells for $80 now, then $80 is the present value of the note that will be worth $100 a year from now. This fee paid as compensation for the current use of assets is known as interest. In other words, the concept of interest describes the cost of having funds tied up in investments or savings.

Furthermore, the time value of money is related to the concept of opportunity cost. The cost of any decision includes the cost of the most forgone alternative. The cost of money is the opportunity cost of holding money in hands instead of investing it. The trade-off between money now (holding money) and money later (investing) depends on, among other things, the rate of interest that can be earned by investing. An investor with money has two options: to spend it right now or to save it. The financial compensation for saving it as against spending it is that the money value will accrue through the compound interest that he will receive from a borrower (the bank account or investment in which he has the money).

Interest Rate Levels

An interest rate is the rate at which interest is paid by a borrower for the use of money that they borrow from a lender.

Learning Objectives

Describe the crowding out phenomenon

Key Takeaways

Key Points

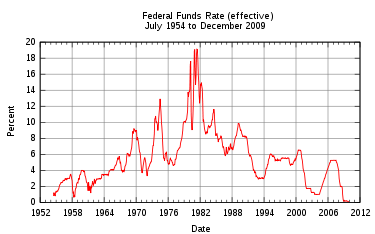

- In the U.S., the Federal Reserve (often referred to as ‘The Fed’) implements monetary policies largely by targeting the federal funds rate.

- Expansionary monetary policy is traditionally used to try to combat unemployment in a recession by lowering interest rates in the hope that easy credit will entice businesses into expanding.

- Contractionary monetary policy is intended to slow inflation in hopes of avoiding the resulting distortions and deterioration of asset values.

- Crowding out is a phenomenon occurring when expansionary fiscal policy causes interest rates to rise, thereby reducing investment spending.

Key Terms

- monetary policy: The process by which the monetary authority of a country controls the supply of money, often targeting a rate of interest for the purpose of promoting economic growth and stability.

An interest rate is the rate at which interest is paid by a borrower for the use of money that they borrow from a lender. Changes in interest rate levels signal the status of the economy. As a vital tool of monetary policy, interest rates are kept at target levels – taking into account variables like investment, inflation, and unemployment – for the purpose of promoting economic growth and stability. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve (often referred to as ‘The Fed’) implements monetary policies largely by targeting the federal funds rate. This is the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, which are the reserves held by banks at the Fed.

Monetary policies are referred to as either expansionary or contractionary. Expansionary policy is traditionally used to try to combat unemployment in a recession by lowering interest rates in the hope that easy credit will entice businesses into expanding. An expansionary policy increases the total supply of money in the economy more rapidly than usual. Contractionary policy is intended to slow inflation in hopes of avoiding the resulting distortions and deterioration of asset values. Contractionary policy increases interest rate levels by expanding the money supply more slowly than usual or even shrinking it. Most central banks around the world assume and expect that lowering interest rates (expansionary monetary policies) would produce the effect of increasing investments and consumptions. However, lowering interest rates can sometimes lead to the creation of massive economic bubbles, when a large amount of investments are poured into the real estate market and stock market.

Crowding Out

Crowding out is a phenomenon occurring when expansionary fiscal policy causes interest rates to rise, thereby reducing investment spending. That means increase in government spending crowds out investment spending. This change in fiscal policy shifts equilibrium in the goods market. A fiscal expansion increases equilibrium income. If interest rates are unchanged, an increase in the level of aggregate demand will follow. This increase in demand must be met by rise in output.

With this increase in equilibrium income, the quantity of money demanded is higher. Because there is an excessive demand for real balances, the interest rate rises. Firms planned spending declines at higher interest rates, thus the aggregate demand falls. The adjustment of interest rates and their impact on aggregate demand dampen the expansionary effect of the increased government spending.

Drivers of Market Interest Rates

Market interest rates are mostly driven by inflationary expectations, alternative investments, risk of investment, and liquidity preference.

Learning Objectives

Calculate the nominal interest rate of a given investment

Key Takeaways

Key Points

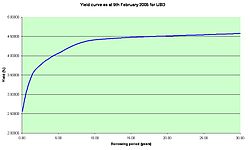

- A market interest rate is the rate at which interest is paid by a borrower for the use of money that they borrow from a lender in the market.

- Economists generally agree that the interest rates yielded by any investment take into account: the risk -free cost of capital, inflationary expectations, the level of risk in the investment, and the costs of the transaction.

- A basic interest rate pricing model for an asset is presented by the following formula: in = ir + pe + rp + lp.

Key Terms

- inflation: An increase in the general level of prices or in the cost of living.

- abscond: To flee; to withdraw from.

- interest rate risk: the potential for loss that arises for bond owners from fluctuating interest rates

- liquidity: Availability of cash over short term: ability to service short-term debt.

A market interest rate is the rate at which interest is paid by a borrower for the use of money that they borrow from a lender in the market.

Factors Influencing Market Interest Rates

Deferred consumption: When money is loaned the lender delays spending the money on consumption goods. According to time preference theory, people prefer goods now to goods later. In a free market there will be a positive interest rate.

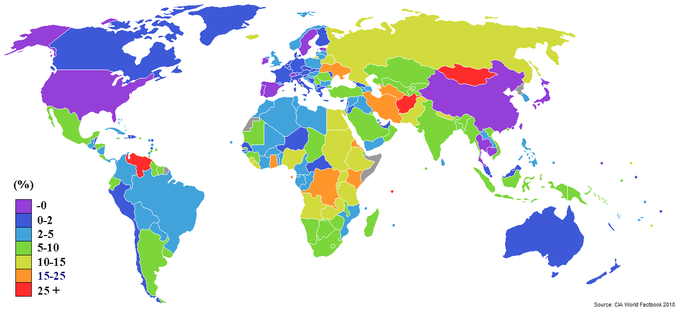

Inflationary expectations: Most economies generally exhibit inflation, meaning a given amount of money buys fewer goods in the future than it will now. The borrower needs to compensate the lender for this. If the inflationary expectation goes up, then so does the market interest rate and vice versa.