Corporate taxes are levied on the income of various entities, stemming from their business operations.

Learning Objectives

Identify how each type of business association is taxed.

Corporate taxes are levied on the income of various entities, stemming from their business operations.

Identify how each type of business association is taxed.

Income taxes in the United States are an enormous and complex issue. Corporate taxes are especially complicated because of the inherent complexities of corporations themselves. Corporations may be taxed on their incomes, property, or their very existence. The types and rates of taxes vary depending on the jurisdiction in which the corporation is organized or acts. Maryland, for example, imposes a tax on corporations organized within its borders based on the number of shares of capital stock they issue.

Corporate taxation differs depending upon the legal form of the corporation. Which legal form to take is driven by the objectives of the company, but taxation also plays a vital role. Tax law contains built-in trade-offs for each corporate form, and companies often must give up some liability protection or flexibility.

A sole proprietorship is a business entity that is owned and run by a single individual. There is no legal distinction between the owner and the business. They are one in the same for tax purposes. The individual reports all income and expenses for the business on his or her personal income tax statement. In other words, the business is not taxed as a separate entity.

There is no method for sheltering tax in a sole proprietorship. Earnings are taxed regardless if they are actually distributed. In addition, the individual is held liable for the actions of the business, meaning claimants can pursue the personal property of the individual should solvency issues arise.

A partnership is a business entity with two or more owners. For tax purposes, partnerships are treated similarly to a sole proprietorship – the owners pay tax on their “distributive share” of the business’s taxable income. The partners must agree on how the income of the business will be allocated. Partners are jointly liable for the operations of the business. Thus, one partner may pursue one or any number of other partners in the case of personal damages or losses.

A C corporation refers to any corporation that is taxed separately from its owners. Although vastly outnumbered by sole proprietorships and partnerships, most of the largest companies in the U.S. are C corporations. Owners of C corporations are personally protected from any liability of the company – an idea known as the corporate veil. In return, the earnings of a C corporation are taxed both on the entity level and the individual level.

The S corporation is a hybrid entity wherein the income, deductions and tax credits of the business are taxed at the shareholder level as opposed to the entity level. However, owners enjoy the same limited liability awarded to C corporations. In exchange for this luxury, rules are placed on the types of corporations that can elect S status:

An LLC, like an S corporation, is a hybrid entity having certain characteristics of both a corporation and a partnership or sole proprietorship. The primary characteristic an LLC shares with a corporation is limited liability, and the primary characteristic it shares with a partnership is taxation on the ownership level. It differs from an S corporation in that there are no restrictions on the number or types of shareholders. It is actually a type of unincorporated association rather than a corporation.

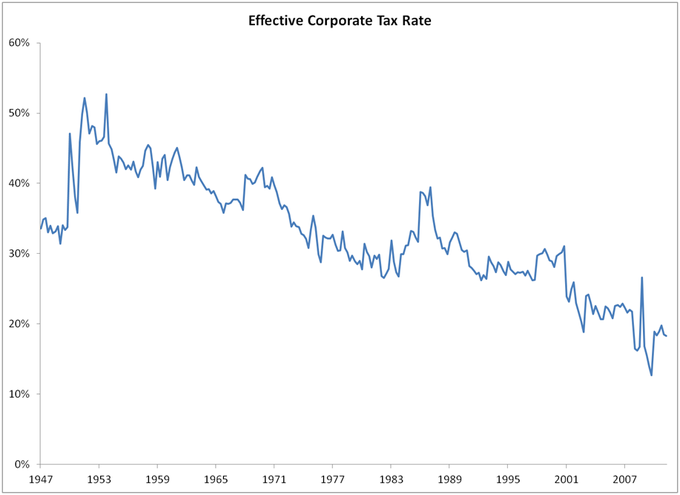

In the United States, taxable income for a corporation is defined as all gross income (sales plus other income minus cost of goods sold and tax exempt income) less allowable tax deductions and tax credits. This income is taxed at a specified corporate tax rate. This rate varies by jurisdiction and is generally the same for different types of income. Some systems have graduated tax rates – corporations with lower levels of income pay a lower rate of tax – or impose tax at different rates for different types of corporations.

In the US, federal rates range from 15% to 35%. States charge rates ranging from 0% to 10%, deductible in computing federal taxable income. Some cities charge rates up to 9%, also deductible in computing Federal taxable income. Corporations are also subject to property tax, payroll tax, withholding tax, excise tax, customs duties and value added tax. However, these are rarely referred to as “corporate tax.”

A tax deduction is a reduction of the amount of income subject to tax.

Identify deductions associated with carrying on a trade or business.

A tax deduction is a sum that can be removed from tax calculations. Specifically, it is a reduction of the income subject to tax. Often these deductions are subject to limitations or conditions. Nearly all jurisdictions that tax business income allow tax deductions for expenses incurred in trading or carrying on the trade or business. However, to be deducted, the expenses must be incurred in furthering the business, such as it must contribute to profit.

Expenses incurred in order to generate profit for a company are referred to as business expenses. These can be categorized into cost of goods sold and ordinary expenses–also knowns as trading or necessary expenses.

Nearly all income tax systems allow a deduction for cost of goods sold. This can be considered an expense or simply a reduction in gross income, which is the starting point for determining Federal and state income tax. Several complexities must be factored in when determining cost of goods sold, including:

According to tax law, the United States allows as a deduction “all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business…” Generally, this business must be regular, continuous, substantial, and entered into with an expectation of profit. Ordinary and necessary expenses tend to be those that are appropriate to the nature of the business, the sort expected to help produce income and promote the business, and those that are not lavish and extravagant.

An example of an ordinary expense is interest paid on debt, or interest expense incurred by a corporation in carrying out its trading activities. Such an expense comes with limitations, though, such as limiting the amount of deductible intrest that can be paid to related parties.

Expenses incurred from holding assets expected to produce income may also be deductible. For example, a deduction may be allowed for loss on sale, exchange, or abandonment of both business and non-business income producing assets. In the United States, a loss on non-business assets is considered a capital loss and deduction of the loss is limited to capital gains.

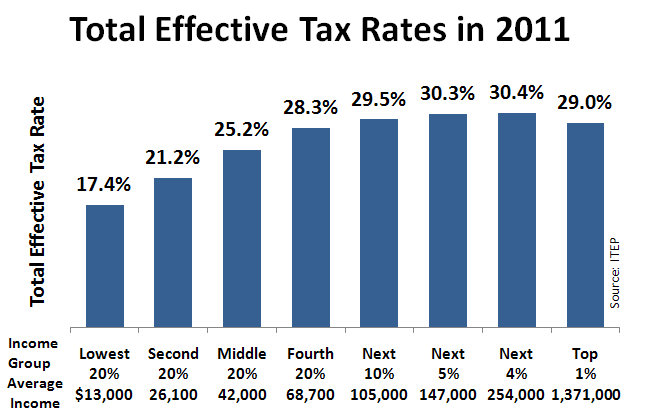

Corporate taxes in the United States are considered to be progressive. That is to say, taxes are charged at a higher rate as income grows. To fully understand the effect of tax deductions, we must consider the marginal tax rate, which is the rate of tax paid on the next or last unit of currency of taxable income. The marginal tax rate is dependent upon a jurisdiction’s tax structure, usually referred to as tax brackets. To determine the after-tax cost of a deductible expense, we simply multiply the cost by one minus the appropriate marginal tax rate.

Tax deductions and tax credits are often incorrectly equated. While a deduction is a reduction of the level of taxable income, a tax credit is a sum deducted from the total amount of tax owed. It is a dollar-for-dollar tax saving. For example, a tax credit of $1,000 reduced taxes owed by $1,000, regardless of the marginal tax rate. A tax credit may be granted in recognition of taxes already paid, as a subsidy, or to encourage investment or other behaviors.

Depreciation is the allocation of expenses associated with assets that contribute to operations over several periods.

Describe the effect depreciation has on calculating a company’s tax burden.

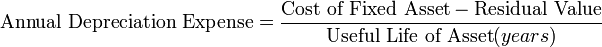

Many tax systems require that the cost of items likely to produce future benefits be capitalized. Such assets include property and capital equipment that represent a commitment of resources over several periods. In accounting, the profits ( net income ) from an activity must be reduced by the costs associated with that activity. When an asset will be used in operations for several periods, tax systems often allow the allocation of the costs to periods in which the assets are used. In the U.S., this allocation is known as depreciation expense. It is important to reasonably estimate the useful life of the asset under depreciation in time-units. Then it is important to calculate the corresponding depreciation rate that will result in extinguishing the value of the asset from the books when the estimated useful life ends. There are several methods for achieving this goal.

The straight-line method of depreciation reduces the book value of an asset by the same amount each period. This amount is determined by dividing the total value of the asset, less its salvage value, by the number of periods in its useful life. This amount is then deducted from income in each applicable period. Straight-line depreciation is the simplest and most-often-used technique.

The economic reasoning behind the straight-line method involves the acceptance that depreciation is an approximation of the rate at which an asset transfers value to the operations of a business. As a result, we should use the most economical, or simplest, method to calculate and incorporate its costs.

The declining balance method of depreciation provides for a higher depreciation expense in the first year of an asset’s life and gradually decreases expenses in subsequent years. This may be a more realistic reflection of the actual expected benefit from the use of the asset because many assets are most useful when they are new. Under this method, the annual depreciation expense is found by multiplying book value of the asset each year by a fixed rate. Since this book value will differ from year to year, the annual depreciation expense will subsequently differ. The most commonly used rate is double the straight-line rate. Since the declining balance method will never fully amortize the original cost of the asset, the salvage value is not considered in determining the annual depreciation.

Activity depreciation methods are not based on time, but on a level of activity. When the asset is acquired, its life is estimated in terms of this level of activity. This could be miles driven for a vehicle or a cycle count for a machine. Each year, the depreciation expense is calculated by multiplying the rate by the actual activity level.

Depreciation expense affects net income in each period of an asset’s useful life. Therefore, it can be deducted from taxes owed in each of these periods. In other words, depreciation allows a company to properly identify the amount of income it generates in a given period. As with all expenses, a dollar of taxes that a company can defer until later is a dollar that can be used in profit generating operations today.

The U.S. federal, state and local governments levy taxes on individuals based on income, property, estate transfers, and/or sales transactions.

Describe each type of tax that can be imposed on an individual.

In the United States, there are an assortment of federal, state, local, and special purpose taxes that are imposed by such jurisdictions on individuals in order to finance government operations. These taxes may be imposed on the same income, property, or activity, often without offset of one tax against another. Taxes may be based on property, income, transactions, importation of goods, business activity, or a variety of factors, and are generally imposed on the type of taxpayer for whom such tax base is relevant.

Individual taxes can generally be defined as either direct or indirect. A direct tax is one imposed upon an individual person or on property, as opposed to a tax imposed upon a transaction. In U.S. constitutional law, direct taxes refer to poll taxes and property taxes, which are based on simple existence or ownership. Indirect taxes, such as sales or value-added tax, are imposed only when a taxable transaction occurs. People have the freedom to engage in or refrain from such transactions, whereas a direct tax is typically imposed upon an individual in an unconditional manner.

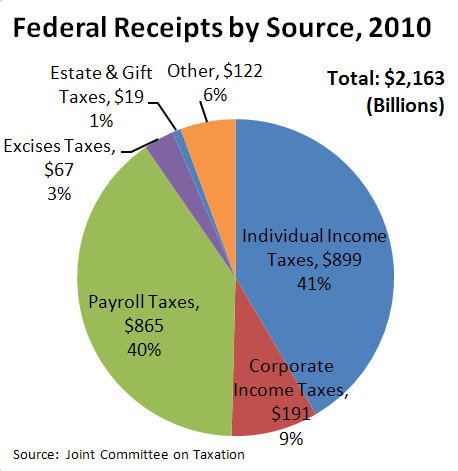

Personal income tax is generally the largest source of tax revenue in the United States. Taxes based on income are imposed at the federal, most state, and some local levels. Income tax is levied on the total income of the individual, less deductions, reducing an individual’s taxable income, and credits, a dollar-for-dollar reduction of total tax liability. The tax system allows for personal exemptions, as well as certain “itemized deductions,” including:

Income tax is often collected on a pay-as-you-earn basis (i.e., witholding taxes from wages). Small corrections are usually made after the end of the tax year. These corrections take one of two forms: payments to the government for taxpayers who have not paid enough during the tax year; and government tax refunds for those who have overpaid.

Federal and many state income tax rates are graduated or progressive–they are higher (graduated) at higher levels of income. The income level at which various tax rates apply for individuals varies by filing status. The income level at which each rate starts generally is higher, therefore, tax is lower for married couples filing a joint return or single individuals filing as head of household. Individuals are subject to federal graduated tax rates from 10% to 35%. State income tax rates vary from 1% to 16%, including local income tax where applicable.

Payroll taxes are imposed on employers and employees and on various compensation bases. These include income tax witholding, social security and medicare taxes, and unemployment taxes.

Sales tax is an indirect tax levied on the state level, including taxes on retail sale, lease and rental of goods, as well as some services. Many cities, counties, transit authorities, and special purpose districts impose an additional local sales tax. Sales tax is calculated as the purchase price times the appropriate tax rate. Tax rates vary widely by jurisdiction from less than 1% to over 10%. Nearly all jurisdictions provide numerous categories of goods and services that are exempt from sales tax or taxed at a reduced rate.

In addition to sales tax, excise taxes are imposed at the federal and state levels on a goods, including alcohol, tobacco, tires, gasoline, diesel fuel, coal, firearms, telephone service, air transportation, unregistered bonds, etc.

Most jurisdictions below the state level impose a tax on interests in real property (land, buildings, and permanent improvements). Property tax is based on fair market value the subject property. The amount of tax is determined annually based on the market value of each property on a particular date. The tax is computed as the determined market value times an assessment ratio times the tax rate.

The estate tax is an excise tax levied on the right to pass property at death. It is imposed on the estate, not the beneficiary. Gift taxes are levied on the giver (donor) of property where the property is transferred for less than adequate consideration. The Federal gift tax is computed based on cumulative taxable gifts, and is reduced by prior gift taxes paid. The Federal estate tax is computed on the sum of taxable estate and taxable gifts, and is reduced by prior gift taxes paid. These taxes are computed as the taxable amount times a graduated tax rate (up to 35%). Taxable values of estates and gifts are the fair market value.