Cash Flow Factors

Cash flow factors are the operational, financial, or investment activities which cause cash to enter or leave the organization.

Learning Objectives

Describe how cash flow factors can be used to improve or evaluate a business

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Cash flow factors can be used to calculate parameters to measure organizational performance.

- Operational cash flows are those originating from the organization’s internal business.

- Financing cash flows are those originating from the issuance of debt or equity.

- Investment cash flows are those originating from assets and capital expenditures.

Key Terms

- parameter: A variable kept constant during an experiment, calculation, or similar.

- liquidity: Availability of cash over short term: ability to service short-term debt.

Definition

Cash flow is the movement of money into or out of a business, project, or financial product. It is usually measured during a specified, finite period of time. Measurement of cash flow can be used for calculating other parameters that give information on a company’s value and situation.

Statement of Cash Flow in a Business’s Financial Statements

A business’s Statement of Cash Flows illustrates its calculated net cash flow. The net cash flow of a company over a period (typically a quarter or a full year) is equal to the change in cash balance over this period: It’s positive if the cash balance increases (more cash becomes available); it’s negative if the cash balance decreases. The total net cash flow is composed of several factors:

- Operational cash flows: Cash received or expended as a result of the company’s internal business activities. This includes cash earnings plus changes to working capital. Over the medium term, this must be net positive if the company is to remain solvent.

- Investment cash flows: Cash received from the sale of long-life assets or spent on capital expenditure, such as, investments, acquisitions, and long-life assets.

- Financing cash flows: Cash received from the issue of debt and equity, or paid out as dividends, share repurchases or debt repayments.

Uses

Cash flow factors can be used for calculating parameters, such as:

- to determine a project’s rate of return or value. The cash flows into and out of projects are used as inputs in financial models, such as internal rate of return and net present value.

- to determine problems with a business’s liquidity. Being profitable does not necessarily mean being liquid. A company can fail because of a shortage of cash even while profitable.

- as an alternative measure of a business’s profits when it is believed that accrual accounting concepts do not represent economic realities. For example, a company may be notionally profitable but generating little operational cash (as may be the case for a company that barters its products rather than selling for cash). In such a case, the company may be deriving additional operating cash by issuing shares or raising additional debt finance.

- can be used to evaluate the “quality” of income generated by accrual accounting. When net income is composed of large non-cash items, it is considered low quality.

- to evaluate the risks within a financial product (e.g., matching cash requirements, evaluating default risk, re-investment requirements, etc)

Cash flow is a generic term used differently depending on the context. It may be defined by users for their own purposes. It can refer to actual past flows or projected future flows. It can refer to the total of all flows involved or a subset of those flows.

Replacement Projects

A replacement project is an undertaking in which the company eliminates a project at the end of its life and substitutes another investment.

Learning Objectives

Analyze a possible replacement projects to determine if it should be implemented

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The cash flow analysis must take all cash flow components into account, such as opportunity costs and depreciation and maintenance expense.

- The replacement project’s cash flows are the additional inflows and outflows to be provided by the prospective replacement project.

- The comparison between the replacement and the current project informs the decision whether to undertake the replacement and, if applicable, at what point replacement should occur.

Key Terms

- capital budgeting: The budgeting process in which a company plans its capital expenditure (the spending on assets of long-term value).

- sunk cost: A cost that has already been incurred and which cannot be recovered to any significant degree.

- Opportunity cost: The cost of an opportunity forgone (and the loss of the benefits that could be received from that opportunity); the most valuable forgone alternative.

Definition

The possibility of replacement projects must be taken into account during the process of capital budgeting and subsequent project management. A replacement project is an undertaking in which the company eliminates a project at the end of its life and substitutes another investment. This replacement project can serve the purpose of replacing an expiring investment with a new, identical one, or replacing an existing investment that is producing unfavorable results with one that management believes will perform better.

When analyzing a project, and ultimately deciding whether it is a good investment decision or not, one focuses on the expected cash flows associated with the project. These cash flows form the basis for the project’s value, usually after implementing a method of discounted cash flow analysis. Most projects have a finite useful life. Analysis can be undertaken in order to determine when the optimum point of replacement will be, as well as if replacement is a viable option in the first place. To accomplish this, one analyzes the cash flows of the current project in relation to the expected cash flows from the replacement project.

Analysis

The net cash flows for a project take into account revenues and costs generated by the project, along with more indirect implications, such as sunk costs, opportunity costs and depreciation costs related to the project. All of these considerations taken together allow management to consider the project’s incremental cash flows, which are inflows and outflows the project produces over predictable periods of time. Discounted cash flow analysis should be undertaken for both the existing project and the potential replacement project. These analyses can then be used to compare the expected profitability of both projects; which will, in theory, lead management to make the right decision regarding the investments.

In general, there will be some sort of cash inflow from ending the old project — for example, from the terminal value realized upon the sale of existing equipment — and a subsequent cash outflow to begin the new project. The loss of expected future cash flows from the previous project, or opportunity cost, must also be taken into account. A general form that can be used to analyze these cash flows is:

Increase in Net Income + (Depreciation on New Investment – Depreciation on Old Investment)

Sunk Costs

Sunk costs are retrospective costs that cannot be recovered, and are therefore irrelevant to future investment decisions in the project which incurs them.

Learning Objectives

Identify sunk costs when making an investment decision

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Only prospective costs should impact an investment decision. Therefore, sunk costs are not to be considered when deciding whether to undertake a project.

- A sunk cost is distinct from an economic loss. A loss may be caused by a sunk cost, however.

- Sunk costs are irrecoverable.

Key Terms

- retrospective: Affecting or influencing past things; retroactive.

Definition

Sunk costs are retrospective costs that have already been incurred and cannot be recovered. Sunk costs are sometimes contrasted with prospective costs, which are future costs that may be incurred or changed if an action is taken.

Impact on Investment Decision

The idea of sunk costs is often employed when analyzing business decisions. In traditional microeconomic theory, only prospective (future) costs are relevant to an investment decision. For example the research and development of a pharmaceutical are retrospective once it is time to market the product. Once spent, such costs are sunk and should have no effect on future pricing decisions. The company will charge market prices whether R&D had cost one dollar or one million dollars. Therefore, the costs of R&D are considered sunk once they are retrospective and irrecoverable. At that point, they have no rational bearing on further investment decisions.

Difference from Economic Loss

The sunk cost is distinct from economic loss. For example, when a car is purchased, it can subsequently be resold; however, it will probably not be resold for the original purchase price. The economic loss is the difference between these values (including transaction costs). The sum originally paid should not affect any rational future decision-making about the car, regardless of the resale value. If the owner can derive more value from selling the car than not selling it, then it should be sold, regardless of the price paid. In this sense, the sunk cost is not a precise quantity, but an economic term for a sum paid in the past, which is no longer relevant to decisions about the future. The sunk cost may be used to refer to the original cost or the expected economic loss. It may also be used as shorthand for an error in analysis due to the sunk cost fallacy, irrational decision-making or, most simply, as irrelevant data.

Opportunity Costs

Opportunity cost refers to the value lost when a choice is made between two mutually exclusive options.

Learning Objectives

Identify opportunity costs when making an economic choice

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Opportunity cost can be seen as the second-best choice available to an economic actor.

- Opportunity cost can be measured monetarily, or more subjectively in terms of pleasure or utility.

- Opportunity cost shows not only that resources are scarce, but also that economic choices are limited.

Key Terms

- explicit costs: a direct payment made to others in the course of running a business, such as wage, rent and materials.

- implicit costs: The opportunity cost equal to what a firm must give up in order to use factors which it neither purchases nor hires.

Definition

Opportunity cost is the cost of any activity measured in terms of the value of the next best alternative forgone (that is not chosen). In other words, it is the sacrifice of the second best choice available to someone, or group, who has picked among several mutually exclusive choices..

Economic Concept

Opportunity cost is a key concept in economics; it relates the scarcity of resources to the mutually exclusive nature of choice. The notion of opportunity cost plays a crucial role in ensuring that scarce resources are allocated efficiently. Thus, opportunity costs are not restricted to monetary or financial costs: the real cost of output forgone, lost time, pleasure or any other benefit that provides utility are also considered implicit. or opportunity, costs. In the context of cash flow analysis, opportunity cost can be thought of as a cash flow that could be generated from assets the organization already owns, if they are not used for the project in question. There is always a trade-off between making decisions on the allocation of assets.

Assessing Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost is assessed not only in monetary or material terms, but also in terms of anything which is of value to the decision maker. For example, a person who desires to watch each of two television programs being broadcast simultaneously, and cannot record one, can only watch one of the desired programs. Therefore, the opportunity cost of watching an NFL football game could be not enjoying the college football game, or vice versa.

Examples

In a restaurant situation, the opportunity cost of eating steak could be trying the salmon. The opportunity cost of ordering both meals could be twofold: the extra $20 to buy the second meal, and reputation with peers, as the diner may be thought of as greedy or extravagant for ordering two meals. A family might decide to use a short period of vacation time to visit Disneyland rather than doing household improvement work. The opportunity cost of having happier children could therefore be a remodeled bathroom.

In a job situation, a person could either choose to run their own bakery, or work as an employee for a restaurant. There are explicit costs on the line, such as the capital necessary to start a business, purchase of all the inputs, and so forth. However, there are possible implicit benefits, such as autonomy and freedom to be “your own boss”, and implicit costs, such as the stress of running your own business. If the individual chooses to run their own bakery, their opportunity costs are the salary that the restaurant would have paid, and the smaller burden of responsibility as an employee instead of an owner.

Externalities

An externality is an effect of an economic action, the cost or benefit of which is shouldered by someone outside the transaction.

Learning Objectives

Explain how externalities can affect different parties to a transaction

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- An externality that is a cost is a negative externality, while one that is a benefit is a positive externality.

- Prices do not reflect externalities because they affect people outside the economic transaction.

- Negative externalities can lead to over-production, while positive externalities can lead to under-production. The former case occurs because the producer does not pay the external cost, while the latter occurs because the benefit is generated without profit.

Key Terms

- benefit: An advantage, help, or aid from something.

Definition

In economics, an externality is a cost or benefit that is not transmitted through prices and is incurred by a party who was not involved as either a buyer or seller of the goods or services. The cost of an externality is a negative externality, or external cost, while the benefit of an externality is a positive externality, or external benefit.

Relation to Prices

In the case of both negative and positive externalities, prices in a competitive market do not reflect the full costs or benefits of producing or consuming a product or service. Producers and consumers may neither bear all of the costs nor reap all of the benefits of the economic activity.

Over- and Under-Production

Standard economic theory states that any voluntary exchange is mutually beneficial to both parties involved in the trade. This is because buyers or sellers would not trade if either thought it was not beneficial.

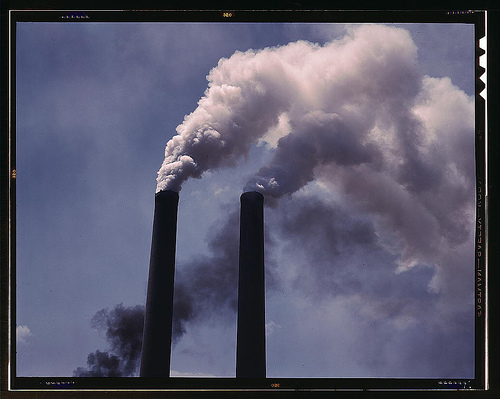

However, an exchange can cause additional effects on third parties. Those who suffer from external costs do so involuntarily, while those who enjoy external benefits do so at no cost. A voluntary exchange may reduce total economic benefit if external costs exist. The person who is affected by the negative externalities in the case of air pollution will see it as lowered utility: either subjective displeasure or potentially explicit costs, such as higher medical expenses.

On the other hand, a positive externality would increase the utility of third parties at no cost to them. Since collective societal welfare is improved, but the providers have no way of monetizing the benefit, less of the good will be produced than would be optimal for society as a whole.

For example, manufacturing that causes air pollution imposes costs on the whole society, while public education is a benefit to the whole society. If there exist external costs such as pollution, the good will be overproduced by a competitive market, as the producer does not take into account the external costs when producing the good.

If there are external benefits, such as in areas of education, too little of the good would be produced by private markets as producers and buyers do not take into account the external benefits to others. Here, overall cost and benefit to society is defined as the sum of the economic benefits and costs for all parties involved.

“Free Rider” Problem

Positive externalities are often associated with the free rider problem. For example, individuals who are vaccinated reduce the risk of contracting the relevant disease for all others around them, and at high levels of vaccination, society may receive large health and welfare benefits. Conversely, any one individual can refuse vaccination, still avoiding the disease by “free riding” on the costs borne by others.

Market Correction

The market-driven approach to correcting externalities is to “internalize” third-party costs and benefits, for example, by requiring a polluter to repair any damage that they cause. But in many cases internalizing costs or benefits is not feasible, especially if the true monetary values cannot be determined.

Tax Rate

The tax rate is the amount of tax expressed as a percentage.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate the different types of tax rates

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The methods used to present a tax rate include: statutory, average, marginal, and effective rates.

- Statutory tax rates are those imposed by law.

- Average tax rate is the total tax liability divided by taxable income.

- Marginal tax rate is the rate at a specific level of spending or income. It is also known as tax “on the last dollar,” earned or spent.

- Effective tax rate describes when varying measures of tax are divided by varying measures of the tax base. It is inconsistently defined in practice.

Key Terms

- margin: Collateral that the holder of a financial instrument has to deposit to cover some or all of the credit risk of their counterparty.

Definition

In a tax system, the tax rate describes the ratio at which a business or person is taxed.

Methods

There are several methods used to present a tax rate:

- statutory

- average

- marginal

- effective

Statutory

A statutory tax rate is the legally imposed rate. An income tax could have multiple statutory rates for different income levels, whereas a sales tax may have a flat statutory rate.

Average

An average tax rate is the ratio of the amount of taxes paid to the tax base (taxable income or spending). To calculate the average tax rate on an income tax, divide the total tax liability by the taxable income.

Marginal

A marginal tax rate is the tax rate that applies to the last dollar of the tax base (taxable income or spending) and is often applied to the change in one’s tax obligation as income rises.

For an individual, this rate can be determined by increasing or decreasing the income earned or spent and calculating the change in taxes payable. An individual’s tax bracket is the range of income for which a given marginal tax rate applies.

The marginal tax rate may increase or decrease as income or consumption increases, although in most countries the tax rate is progressive in principle. In such cases, the average tax rate will be lower than the marginal tax rate. For instance, an individual may have a marginal tax rate of 45%, but pay an average tax of half this amount.

In a jurisdiction with a flat tax on earnings, every taxpayer pays the same percentage of income, regardless of income or consumption. Some proponents of this system propose to exempt a fixed amount of earnings (such as the first $10,000) from the flat tax.

Marginal tax rates may be published explicitly, together with the corresponding tax brackets, but they can also be derived from published tax tables showing the tax for each income. It may be calculated by noting how tax changes with changes in pre-tax income, rather than with taxable income.

Effective

The term effective tax rate has significantly different meanings when used in different contexts or by different sources. Generally it means that some amount of tax is divided by some amount of income or other tax base. In U.S. income tax law, the term is used in relation to determining whether a foreign income tax on specific types of income exceeds a certain percentage of U.S. tax that might apply on such income.

The popular press, Congressional Budget Office, and various think tanks have used the term to refer to varying measures of tax divided by varying measures of income, with little consistency in definition. An effective tax rate may incorporate econometric, estimated, or assumed adjustments to actual data, or may be based entirely on assumptions or simulations. It also incorporates tax breaks or exemptions.

Depreciation

Depreciation is the process by which an asset is used up, and its cost is allocated over a period of time.

Learning Objectives

Describe the relationship between allocation of cost and the matching principle when calculating depreciation

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Fair value depreciation is an estimate of the market value of an asset.

- The cost of an asset that is to be allocated by depreciation is the amount paid for it minus any salvage value it will have at the end of its useful life.

- Methods used for apportioning the cost over a period of time include fixed percentage, straight-line, and declining balance.

Key Terms

- allocate: To distribute according to a plan.

Definition

Depreciation refers to two very different but related concepts: the decrease in value of assets (fair value depreciation), and the allocation of the cost of assets to periods in which the assets are used (depreciation with the matching principle ).

Fair Value Depreciation

Fair value depreciation affects the values of businesses and entities. It is a concept used in accounting and economics, defined as a rational and unbiased estimate of the potential market price of a good, service, or asset, taking into account the amount at which the asset could be bought or sold in a current transaction between willing parties.

Allocation of Cost with Matching Principle

The allocation of the cost of an asset to periods in which it is used up affects net income. Any business or income producing activity using tangible assets incurs costs related to those assets. In determining the net income from an activity, the receipts from the activity must be reduced by appropriate costs.

One such cost is the cost of assets used but not currently consumed in the activity. Such costs must be allocated to the period of use. Where the assets produce benefit in future periods, the matching principle of accrual accounting dictates that those costs must be deferred rather than treated as a current expense.

The business records depreciation expense as an allocation of such costs for financial reporting. The costs are allocated in a rational and systematic manner as a depreciation expense to each period in which the asset is used, beginning when the asset is placed in service.

Generally this involves four criteria:

- the cost of the asset

- the expected salvage value, also known as residual value of the asset

- the estimated useful life of the asset

- a method of apportioning the cost over such life.

The cost of an asset so allocated is the difference between the amount paid for the asset and the salvage value.

Methods

Depreciation is any method of allocating net cost to those periods expected to benefit from use of the asset. Generally the cost is allocated as a depreciation expense, among the periods in which the asset is expected to be used. Such expense is recognized by businesses for financial reporting and tax purposes. Methods of computing depreciation may vary by asset for the same business. Methods may be specified in the accounting or tax rules of a country. Several standard methods of computing depreciation expense may be used, including:

- fixed percentage

- straight line

- declining balance method

Depreciation expense generally begins when the asset is placed in service. For instance, a depreciation expense of 100 dollars per year for 5 years may be recognized for an asset costing 500 dollars.

Elective Expensing

Section 179 of the IRS code allows some pieces of property to be expensed entirely when they are purchased, rather than depreciated.

Learning Objectives

Summarize section 179 of the tax code and how it applies to businesses

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Usually this provision applies to small businesses because there are limitations on what and how much property can be expensed.

- Though buildings were not originally eligible, a 2010 law included them.

- The total deduction for a year cannot exceed the person’s income for that year.

Key Terms

- deduction: A sum that can be removed from tax calculations; something that is written off.

Definition

Section 179 of the United States Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C. § 179) allows a taxpayer to elect to deduct the cost of certain types of property on their income taxes as an expense, rather than requiring the cost of the property to be capitalized and depreciated. This property is generally limited to tangible, depreciable, personal property which is acquired by purchase for use in the active conduct of a trade or business. This can afford considerable tax savings in some circumstances.

Property

Buildings were not eligible for section 179 deductions prior to the passage of the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010; however, qualified real property may now be deducted. Depreciable property that is not eligible for a section 179 deduction is still deductible over a number of years through MACRS depreciation according to sections 167 and 168. The 179 election is optional, and the eligible property may be depreciated according to sections 167 and 168 if preferable for tax reasons. Furthermore, the 179 election may be made only for the year the equipment is placed in use and is waived if not taken for that year. However, if the election is made, it is irrevocable unless special permission is given.

Limitations

The § 179 election is subject to three important limitations:

- There is a dollar limitation. Under section 179(b)(1), the maximum deduction a taxpayer may elect to take in a year is 500,000 dollars in 2010 and 2011, 125,000 dollars in 2012, and 25,000 dollars for years beginning after 2012.

- If a taxpayer places more than 2 million dollars worth of section 179 property into service during a single taxable year, the 179 deduction is reduced, dollar for dollar, by the amount exceeding the 2 million threshold. This threshold is further reduced to 500,000 dollars beginning in 2012, and then 200,000 dollars afterward.

- Lastly, the section provides that a taxpayer’s 179 deduction for any taxable year may not exceed the taxpayer’s aggregate income from the active conduct of trade or business by the taxpayer for that year. If, for example, the taxpayer’s net trade or business income from active conduct of trade or business was 72,500 dollars in 2006, then the deduction cannot exceed 72,500 dollars that year. However, any deduction not allowed in a given year under this limitation can be carried over to the next year.

Licenses and Attributions

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC licensed content, Specific attribution

- liquidity. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/liquidity. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cash flow. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- parameter. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | Cash | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blatantworld/4149529614/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Opportunity cost. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Linh Luong, Project Management 101. September 17, 2013. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:f0a795f0-0309-43f1-b93c-eb772e5d4c5d. License: CC BY: Attribution

- capital budgeting. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- sunk cost. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | Cash | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blatantworld/4149529614/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Replacement Window Installation | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/andersenwindows/5738170170/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Sunk cost. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunk_cost. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- retrospective. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | Cash | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blatantworld/4149529614/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Replacement Window Installation | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/andersenwindows/5738170170/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Sunk Boat | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/janeladeimagens/262555625/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Opportunity cost. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- explicit costs. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- implicit costs. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | Cash | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blatantworld/4149529614/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Replacement Window Installation | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/andersenwindows/5738170170/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Sunk Boat | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/janeladeimagens/262555625/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Scales Of Justice | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vaxzine/485424742/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Externalities. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- benefit. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | Cash | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blatantworld/4149529614/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Replacement Window Installation | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/andersenwindows/5738170170/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Sunk Boat | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/janeladeimagens/262555625/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Scales Of Justice | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vaxzine/485424742/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Smoke stacks (LOC) | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2179929940/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Tax rate. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tax_rate. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- margin. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | Cash | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blatantworld/4149529614/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Replacement Window Installation | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/andersenwindows/5738170170/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Sunk Boat | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/janeladeimagens/262555625/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Scales Of Justice | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vaxzine/485424742/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Smoke stacks (LOC) | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2179929940/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Tax | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/[email protected]/6629120915/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Depreciation. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- allocate. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | Cash | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blatantworld/4149529614/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Replacement Window Installation | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/andersenwindows/5738170170/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Sunk Boat | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/janeladeimagens/262555625/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Scales Of Justice | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vaxzine/485424742/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Smoke stacks (LOC) | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2179929940/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Tax | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/[email protected]/6629120915/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | In-n-Out-burger—eating | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/lifeontheedge/458706241/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Section 179 depreciation deduction. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Section_179_depreciation_deduction. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- deduction. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- All sizes | Cash | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/blatantworld/4149529614/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Replacement Window Installation | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/andersenwindows/5738170170/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Sunk Boat | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/janeladeimagens/262555625/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Scales Of Justice | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vaxzine/485424742/sizes/o/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Smoke stacks (LOC) | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2179929940/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Tax | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/[email protected]/6629120915/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | In-n-Out-burger—eating | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/lifeontheedge/458706241/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- All sizes | Truck load of ponderosa pine, Edward Hines Lumber Co.noperations in Malheur National Forest, Grant County, Oregon (LOC) | Flickr – Photo Sharing!. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2178329189/sizes/m/in/photostream/. License: CC BY: Attribution