Price Risk

Price risk is the risk that the market price of a bond will fall, usually due to a rise in the market interest rate.

Learning Objectives

Identify a bond’s price risk

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The market price of bonds will decrease in value when the generally prevailing interest rates rise and vice versa.

- Unless you plan to buy or sell them in the open market, changing interest rates do not affect the interest payments to the bondholder.

- Price changes in a bond will immediately affect mutual funds that hold these bonds. If the value of the bonds in their trading portfolio falls, the value of the portfolio also falls.

Key Terms

- mutual funds: A type of professionally-managed collective investment vehicle that pools money from many investors to purchase securities. While there is no legal definition, the term is most commonly applied only to those collective investment vehicles that are regulated, available to the general public and open-ended in nature.

Interest rates and bond prices carry an inverse relationship. Bond price risk is closely related to fluctuations in interest rates. Fixed-rate bonds are subject to interest rate risk, meaning that their market prices will decrease in value when the generally prevailing interest rates rise. Since the payments are fixed, a decrease in the market price of the bond means an increase in its yield. When the market interest rate rises, the market price of bonds will fall, reflecting investors ‘ ability to get a higher interest rate on their money elsewhere — perhaps by purchasing a newly-issued bond that already features the new higher interest rate. On the flip side, if the prevailing interest rate were on the decline, investors would naturally buy bonds that pay lower rates of interest. This would force bond prices up.

Unless you plan to buy or sell them in the open market, changing interest rates do not affect the interest payments to the bondholder, so long-term investors who want a specific amount at the maturity date do not need to worry about price swings in their bonds and do not suffer from interest rate risk. However, because of the interest rate risk, bonds with longer terms are more risky than bonds with shorter terms.

Price changes in a bond will immediately affect mutual funds that hold these bonds. If the value of the bonds in their trading portfolio falls, the value of the portfolio also falls. This can be damaging for professional investors such as banks, insurance companies, pension funds and asset managers (irrespective of whether the value is immediately “marked to market” or not). If there is any chance a holder of individual bonds may need to sell his bonds and “cash out”, interest rate risk could become a real problem.

Bond prices can become volatile depending on the credit rating of the issuer – for instance if the credit rating agencies like Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s upgrade or downgrade the credit rating of the issuer. An unanticipated downgrade will cause the market price of the bond to fall. As with interest rate risk, this risk does not affect the bond’s interest payments (provided the issuer does not actually default), but puts at risk the market price, which affects mutual funds holding these bonds, and holders of individual bonds who may have to sell them.

Reinvestment Risk

Reinvestment risk is the risk that a bond is repaid early, and an investor has to find a new place to invest with the risk of lower returns.

Learning Objectives

Define reinvestment risk

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Reinvestment risk is more likely when interest rates are declining.

- Reinvestment risk affects the yield-to- maturity of a bond, which is calculated on the premise that all future coupon payments will be reinvested at the interest rate in effect when the bond was first purchased.

- Two factors that have a bearing on the degree of reinvestment risk are maturity of the bond and the coupon interest rate.

Key Terms

- Yield to maturity: The Yield to maturity (YTM) or redemption yield of a bond or other fixed-interest security, such as gilts, is the internal rate of return (IRR, overall interest rate) earned by an investor who buys the bond today at the market price, assuming that the bond will be held until maturity, and that all coupon and principal payments will be made on schedule.

Reinvestment risk is one of the main genres of financial risk. The term describes the risk that a particular investment might be canceled or stopped somehow, and that one may have to find a new place to invest their money with the risk being there might not be a similarly attractive investment available. This primarily occurs if bonds (which are portions of loans to entities) are paid back earlier than expected.

The risk resulting from the fact that interest or dividends earned from an investment may not be able to be reinvested in such a way that they earn the same rate of return as the invested funds that generated them. Reinvestment risk is more likely when interest rates are declining. For example, falling interest rates may prevent bond coupon payments from earning the same rate of return as the original bond. Pension funds are also subject to reinvestment risk. Especially with the short-term nature of cash investments, there is always the risk that future proceeds will have to be reinvested at a lower interest rate.

Reinvestment risk affects the yield-to-maturity of a bond, which is calculated on the premise that all future coupon payments will be reinvested at the interest rate in effect when the bond was first purchased.

Two factors that have a bearing on the degree of reinvestment risk are:

Maturity of the bond – The longer the maturity of the bond, the higher the likelihood that interest rates will be lower than they were at the time of the bond purchase.

Interest rate on the bond – The higher the interest rate, the bigger the coupon payments that have to be reinvested, and, consequently, the reinvestment risk. Zero coupon bonds are the only fixed-income instruments to have no reinvestment risk, since they have no interim coupon payments.

Comparing Price Risk and Reinvestment Risk

Price risk is positively correlated to changes in interest rates, while reinvestment risk is inversely correlated.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate between price risk and reinvestment risk

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Price risk and reinvestment risk are both the uncertainty associated with the effects of changes in market interest rates.

- Price risk and changes in interest rates are positively correlated.

- Reinvestment risk and changes in interest rates are inversely correlated.

Key Terms

- duration: A measure of the sensitivity of the price of a financial asset to changes in interest rates, computed for a simple bond as a weighted average of the maturities of the interest and principal payments associated with it.

Overview

Price risk and reinvestment risk both represent the uncertainty associated with the effects of changes in market interest rates. Both types of interest rate risks are important considerations in investments, corporate financial planning, and banking.

Price Risk

Price risk is the uncertainty associated with potential changes in the price of an asset caused by changes in interest rate levels in the economy. The price risk is sometimes referred to as maturity risk since the greater the maturity of an investment (the greater the duration), the greater the change in price for a given change in interest rates. Bond market prices will decrease in value when the generally prevailing interest rates rise (price risk is on the rise). Since the payments are fixed, a decrease in the market price of the bond means an increase in its yield. When the market interest rate rises, the market price of bonds will fall, reflecting investors ‘ ability to get a higher interest rate on their money elsewhere — perhaps by purchasing a newly issued bond that already features the newly higher interest rate. When interest rates fall, bond prices increase, and there is less price risk. To sum up, price risk and interest rates are positively correlated.

Reinvestment Risk

Reinvestment risk is the risk that a particular investment might be canceled or stopped somehow, and that one may have to find a new place to invest their money with the risk that there might not be a similarly attractive investment available. This primarily occurs if bonds (which are portions of loans to entities) are paid back earlier than expected. When interest rates increase, there is less likelihood that a bond is called and paid back before maturity. So there is little reinvestment risk. When interest rates decrease, there is more likelihood that the bond is called and paid back earlier than expected. There is, accordingly, more reinvestment risk. Reinvestment risk and interest rates are inversely correlated.

Discussion

In summary, price risk and reinvestment risk are two main financial risks resulting from changes in interest rates. The former is positively correlated to interest rates, while reinvestment risk is inversely correlated to fluctuations in interest rates.

Default Risk

Default risk is the risk that a bond issuer will default on any type of debt by failing to make payments which it is obligated to make.

Learning Objectives

Define default risk

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- With default risk, the risk is primarily that of the bondholder and includes lost principal and interest, disruption to cash flows, and increased collection costs.

- To reduce the bondholders’ credit risk, the lender may perform a credit check on the prospective borrower and may require the issuer to take out appropriate insurance.

- A company’s bondholders may lose much or all their money if the company goes bankrupt. There is no guarantee of how much money will remain to repay bondholders.

Key Terms

- liquidated: In law, liquidation is the process by which a company (or part of a company) is brought to an end and the assets and property of the company redistributed.

- insolvent: Unable to pay one’s bills as they fall due.

Default risk (or credit risk) of a bond refers to the risk that a bond issuer will default on any type of debt by failing to make payments which it is obligated to do. The risk is primarily that of the bondholder and includes lost principal and interest, disruption to cash flows, and increased collection costs. The loss may be complete or partial and can arise in a number of circumstances. For example, a company is unable to repay amounts secured by a fixed or floating charge over the assets of the company, a business or consumer does not pay a trade invoice when due, a business does not pay an employee’s earned wages when due, a business or government bond issuer does not make a payment on a coupon or principal payment when due, an insolvent insurance company does not pay a policy obligation, and an insolvent bank won’t return funds to a depositor.

To reduce the bondholders’ credit risk, the lender may perform a credit check on the prospective borrower, may require the issuer to take out appropriate insurance, such as mortgage insurance or seek security or guarantees of third parties, besides other possible strategies. In general, the higher the risk, the higher will be the interest rate that the issuer will have to pay.

A company’s bondholders may lose much or all their money if the company goes bankrupt. Under the laws of many countries (including the United States and Canada), bondholders are in line to receive the proceeds of the sale of the assets of a liquidated company ahead of some other creditors. Bank lenders, deposit holders (in the case of a deposit taking institution such as a bank), and trade creditors may take precedence.

There is no guarantee of how much money will remain to repay bondholders. As an example, after an accounting scandal and a Chapter 11 bankruptcy at the giant telecommunications company Worldcom, in 2004 its bondholders ended up being paid 35.7 cents on the dollar. In a bankruptcy involving reorganization or recapitalization, as opposed to liquidation, bondholders may end up having the value of their bonds reduced, often through an exchange for a smaller number of newly issued bonds.

Bond Rating System

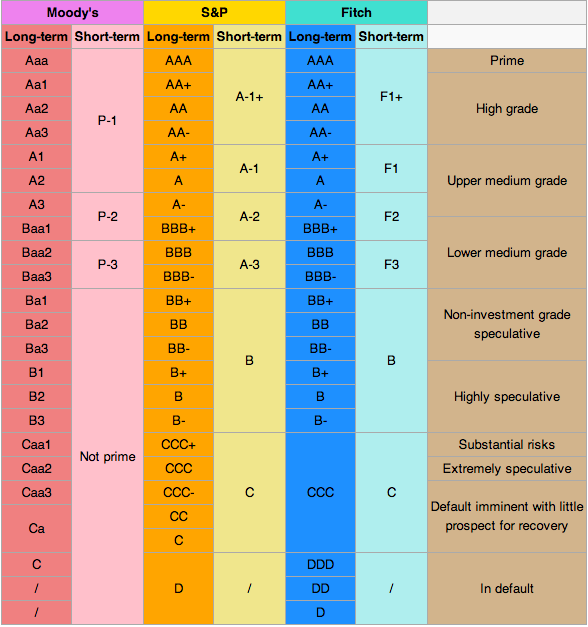

The credit rating is a financial indicator assigned by credit rating agencies; bond ratings below BBB-/Baa are considered junk bonds.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the role of NRSROs in the bond market

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- In investment, the bond credit rating assesses the credit worthiness of a corporation ‘s or government debt issues.

- The credit rating is a financial indicator to potential investors of debt securities, such as bonds. These are assigned by credit rating agencies such as Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch Ratings to have letter designations (such as AAA, B, CC) which represent the quality of a bond.

- Bond ratings below BBB-/Baa are considered not to be investment grade and are colloquially called junk bonds.

Key Terms

- asset-backed securities: An asset-backed security is a security that has value and income payments derived from and collateralized (or “backed”) by a specified pool of underlying assets. The pool of assets is typically a group of small and illiquid assets that are unable to be sold individually.

In investment, the bond credit rating assesses the credit worthiness of a corporation’s or government’s debt issues. It is analogous to credit ratings for individuals.The credit rating is a financial indicator to potential investors of debt securities, such as bonds. These are assigned by credit rating agencies such as Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch Ratings to have letter designations (such as AAA, B, CC), which represent the quality of a bond. Bond ratings below BBB-/Baa are considered to be not investment grade and are colloquially called “junk bonds. ”

Credit rating agencies registered as such with the SEC are “Nationally recognized statistical rating organizations. ” The following firms are currently registered as NRSROs: A.M. Best Company, Inc.; DBRS Ltd.; Egan-Jones Rating Company; Fitch, Inc.; Japan Credit Rating Agency, Ltd.; LACE Financial Corp.; Moody’s Investors Service, Inc.; Rating and Investment Information, Inc.; and Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services.

Under the Credit Rating Agency Reform Act, an NRSRO may be registered with respect to up to five classes of credit ratings: (1) financial institutions, brokers, or dealers; (2) insurance companies; (3) corporate issuers; (4) issuers of asset-backed securities; and (5) issuers of government securities, municipal securities, or securities issued by a foreign government. S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch dominate the market with approximately 90-95% of world market share.

Moody’s assigns bond credit ratings of Aaa, Aa, A, Baa, Ba, B, Caa, Ca, C, with WR and NR as withdrawn and not rated. Standard & Poor’s and Fitch assign bond credit ratings of AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, CCC, CC, C, and D.

A bond is considered investment grade or IG if its credit rating is BBB- or higher by Standard & Poor’s or Baa3 or higher by Moody’s or BBB (low) or higher by DBRS. Generally, they are bonds that are judged by the rating agency as likely enough to meet payment obligations that banks are allowed to invest in them. Ratings play a critical role in determining how much companies and other entities that issue debt, including sovereign governments, have to pay to access credit markets (i.e., the amount of interest they pay on their issued debt). The threshold between investment-grade and speculative-grade ratings has important market implications for issuers’ borrowing costs. Bonds that are not rated as investment-grade bonds are known as high-yield bonds or more derisively as junk bonds. The risks associated with investment-grade bonds (or investment-grade corporate debt) are considered significantly higher than those associated with first-class government bonds.

Bankruptcy and Bond Value

There is no guarantee of how much money will remain to repay bondholders in a bankruptcy, therefore, the value of the bond is uncertain.

Learning Objectives

Identify which stakeholders take precedence in receiving cash from a bankrupt business

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- When a business is unable to service its debt or pay its creditors, it or its creditors can file with a federal bankruptcy court for protection under either Chapter 7 or Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy code.

- If a company goes bankrupt, its bondholders will often receive some money back (the recovery amount).

- In a bankruptcy involving reorganization or recapitalization, as opposed to liquidation, bondholders may end up having the value of their bonds reduced, often through an exchange for a smaller number of newly-issued bonds.

Key Terms

- liquidation: The selling of the assets of a business as part of the process of dissolving the business.

- recapitalization: A restructuring of a company’s mixture of equity and debt.

A company’s bondholders may lose much or all their money if the company goes bankrupt. Under the laws of many countries (including the United States and Canada), bondholders are in line to receive the proceeds of the sale of the assets of a liquidated company ahead of some other creditors.

Bank lenders, deposit holders (in the case of a deposit-taking institution such as a bank) and trade creditors may take precedence. However, compared to equity holders, bondholders also enjoy a measure of legal protection: under the law of most countries, if a company goes bankrupt, its bondholders will often receive some money back (the recovery amount), whereas the company’s equity stock often ends up valueless.

When a business is unable to service its debt or pay its creditors, the business or its creditors can file with a federal bankruptcy court for protection under either Chapter 7 or Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy code. In Chapter 7, the business ceases operations, a trustee sells all of its assets, and then distributes the proceeds to its creditors. Any residual amount is returned to the owners of the company. In Chapter 11, in most instances, the debtor remains in control of its business operations as a debtor in possession, and is subject to the oversight and jurisdiction of the court.

There is no guarantee of how much money will remain to repay bondholders, therefore, the value of the bond is uncertain. As an example, after an accounting scandal and a chapter 11 bankruptcy at the giant telecommunications company Worldcom in 2004, its bondholders ended up being paid 35.7 cents on the dollar. In a bankruptcy involving reorganization or recapitalization, as opposed to liquidation, bondholders may end up having the value of their bonds reduced, often through an exchange for a smaller number of newly-issued bonds.

Licenses and Attributions

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

CC licensed content, Specific attribution

- Bond (finance). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bond_(finance). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- mutual funds. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e5/Durvexity.GIF. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Reinvestment risk. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Yield to maturity. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e5/Durvexity.GIF. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

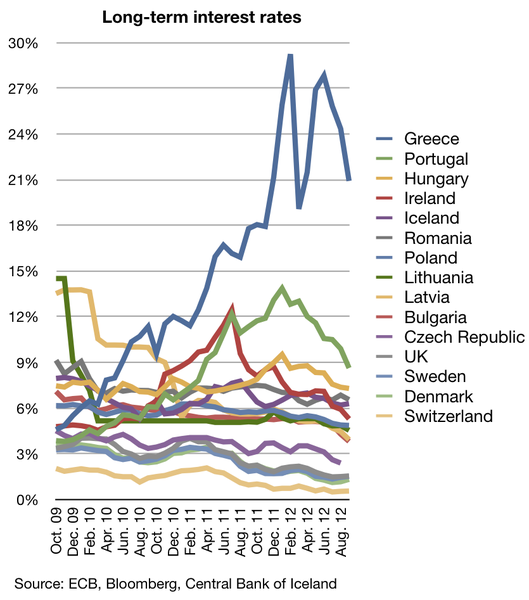

- Long term interest rates. Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Reinvestment risk. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bond (finance). Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- duration. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

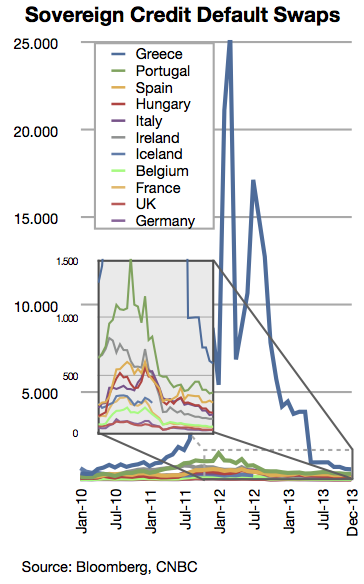

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Long term interest rates. Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

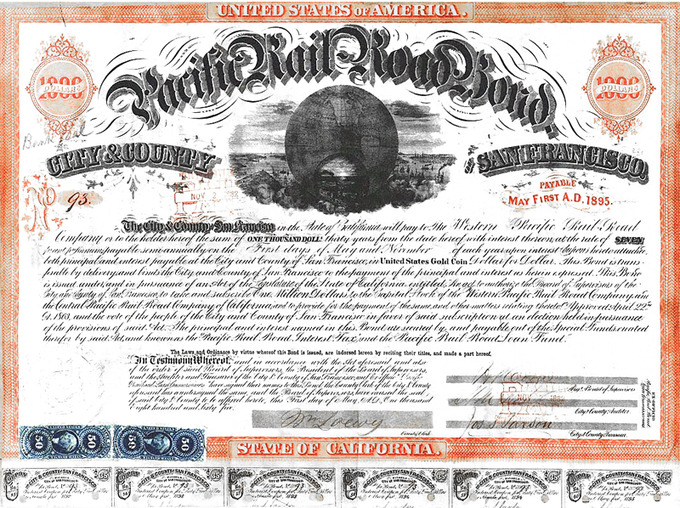

- San Francisco Pacific Railroad Bond WPRR 1865. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bond (finance). Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Credit risk. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- insolvent. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- liquidated. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Long term interest rates. Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- San Francisco Pacific Railroad Bond WPRR 1865. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bond rating. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- asset-backed securities. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Long term interest rates. Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- San Francisco Pacific Railroad Bond WPRR 1865. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bond rating. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Bond (finance). Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chapter 11, Title 11, United States Code. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- recapitalization. Provided by: Wiktionary. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- liquidation. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/liquidation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Long term interest rates. Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- San Francisco Pacific Railroad Bond WPRR 1865. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Bond rating. Provided by: Wikipedia. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tallahassee FL Bankruptcy Courthouse01. Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike