112 Exchange Rates and Risk

Learning Objectives

- Describe exchange rate risk.

- Identify transaction, translation, and economic risks.

- Describe a natural hedge.

- Explain the use of forward contracts as a hedge.

- List the characteristics of an option contract.

- Describe the payoff to the holder and writer of a call option.

- Describe the payoff to the holder and writer of a put option.

The managers of companies that operate in the global marketplace face additional complications when managing the riskiness of their cash flows compared to domestic companies. Managers must be aware of differing business climates and customs and operate under multiple legal systems. Often, business must be conducted in multiple languages. Geopolitical events can impact business relationships. In addition, the company may receive cash flows and make payments in multiple currencies.

Exchange Rates

The costs to companies are impacted when the prices of the raw materials they use change. Very little coffee is grown in the United States. This means that all of those coffee beans that Starbucks uses in its espresso machines in Seattle, New York, Miami, and Houston were bought from suppliers outside of the United States. Brazil is the largest coffee-producing country, exporting about one-third of the world’s coffee.6 When a company purchases raw materials from a supplier in another country, the company needs not just money but the money that is used in that country to make the purchase. Thus, the company is concerned about the exchange rate, or the price of the foreign currency.

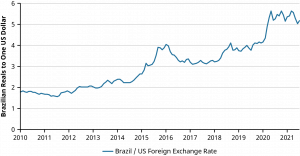

The currency used in Brazil is called the Brazilian real. Figure 12.2 shows how many Brazilian reals could be purchased for $1.00 from 2010 through the first quarter of 2021. In March 2021, 5.4377 Brazilian reals could be purchased for $1.00. This will often be written in the form of

BRL is an abbreviation for Brazilian real, and USD is an abbreviation for the US dollar. This price is known as a currency exchange rate, or the rate at which you can exchange one currency for another currency.

If you know the price of $1.00 is 5.4377 Brazilian reals, you can easily find the price of Brazilian reals in US dollars. Simply divide both sides of the equation by 5.4377, or the price of the US dollar:

If you have US dollars and want to purchase Brazilian reals, it will cost you $0.1839 for each Brazilian real you want to buy.

The foreign exchange rate changes in response to demand for and supply of the currency. In early 2020, the exchange rate was USD 1 = BRL4. In other words, $1 purchased fewer reals in early 2020 than in it did a year later. Because you receive more reals for each dollar in 2021 than you would have a year earlier, the dollar is said to have appreciated relative to the Brazilian real. Likewise, because it takes more Brazilian reals to purchase $1.00, the real is said to have depreciated relative to the US dollar.

Exchange Rate Risks

Starbucks, like other firms that are engaged in international business, faces currency exchange rate risk. Changes in exchange rates can impact a business in several ways. These risks are often classified as transaction, translation, or economic risk.

Transaction Risk

Transaction risk is the risk that the value of a business’s expected receipts or expenses will change as a result of a change in currency exchange rates. If Starbucks agrees to pay a Brazilian coffee grower seven million Brazilian reals for an order of one million pounds of coffee beans, Starbucks will need to purchase Brazilian reals to pay the bill. How much it will cost Starbucks to purchase these Brazilian reals depends on the exchange rate at the time Starbucks makes the purchase.

In March 2021, with an exchange rate of USD 0.1839 = BRL 1, it would have cost Starbucks $0.1839 × 7,000,000 = $1,287,300 to purchase the reals needed to receive the one million pounds of coffee beans. If, however, Starbucks agreed in March to purchase the coffee beans several months later, in July, Starbucks would not have known then what the exchange rate would be when it came time to complete the transaction. Although Starbucks would have locked in a price of BRL 7,000,000 for one million pounds of coffee beans, it would not have known what the coffee beans would cost the company in terms of US dollars.

If the US dollar appreciated so that it cost less to purchase each Brazilian real in July, Starbucks would find that it was paying less than $1,287,300 for the coffee beans. For example, suppose the dollar appreciated so that the exchange rate was USD 0.1800=BRL 1 in July 2021. Then the coffee beans would only cost Starbucks $ 0.1800 × 7,000,000 = $1,260,000.

On the other hand, if the US dollar depreciated and it cost more to purchase each Brazilian real, then Starbucks would find that its dollar cost for the coffee beans was higher than it expected. If the US dollar depreciated (and the Brazilian real appreciated) so that the exchange rate was USD 0.2000 = BRL 1 in July 2021, then the coffee beans would cost Starbucks $0.2000 × 7,000,000 = $1,000,400. This uncertainty regarding the dollar cost of the coffee beans Starbucks would purchase to make its lattes is an example of transaction risk.

A global company such as Starbucks has transaction risk not only because it is purchasing raw materials in foreign countries but also because it is selling its product—and thus collecting revenue—in foreign countries. Customers in Japan, for example, spend Japanese yen when they purchase a Starbucks cappuccino, coffee mug, or bag of coffee beans. Starbucks must then convert these Japanese yen to US dollars to pay the expenses that it incurs in the United States to produce and distribute these products.

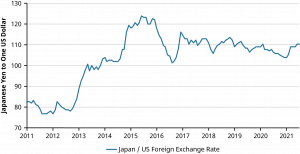

The Japanese yen–US dollar foreign exchange rates from 2011 through the first quarter of 2021 are shown in Figure 12.3. In 2012, $1.00 could be purchased with fewer than 80 Japanese yen. In 2015, it took over 120 yen to purchase $1.00.

If a company is receiving yen from customers and paying expenses in dollars, the company is harmed when the yen depreciates relative to the dollar, meaning that the yen the company receives from its customers can be exchanged for fewer dollars. Conversely, when the yen appreciates, it takes fewer yen to purchase each dollar; this appreciation of the yen benefits companies with revenues in yen and expenses in dollars.

Think It Through

Projecting Sales in US Dollars

The managers of a firm think that the exchange rate of Japanese yen to US dollars will be JPY 100 = USD 1 next year. If the company thinks that it will have sales of 50 million yen next year, how much will it project these sales will be worth in dollars? What happens if the actual exchange rate over the next year is JPY 120 = USD 1?

Solution:

An exchange rate of JPY 100 = USD 1 implies that JPY 1 = USD 0.0100. If the company expects to have sales of JPY 50,000,000, it is expecting sales to be worth USD 500,000. If the exchange rate is really JPY 120 = USD 1, this is the same as JPY 1 = USD 0.0083. With this exchange rate, JPY 50,000,000 in sales would be equivalent to USD 415,000. The company would receive $85,000 less from these sales in Japan than it was expecting, even if it met its goals as far as the number of units of items sold.

Translation Risk

In addition to the transaction risk, if Starbucks holds assets in a foreign country, it faces translation risk. Translation risk is an accounting risk. Starbucks might purchase a coffee plantation in Costa Rica for 120 million Costa Rican colones. This land is an asset for Starbucks, and as such, the value of it should appear on the company’s balance sheet.

The balance sheet for Starbucks is created using US dollar values. Thus, the value of the coffee plantation has to be translated to dollars. Because exchange rates are volatile, the dollar value of the asset will vary depending on the day on which the translation takes place. If the exchange rate is 500 colones to the dollar, then this coffee plantation is an asset with a value of $240,000. If the Costa Rican colón depreciates to 600 colones to the dollar, then the asset has a value of only $200,000 when translated using this exchange rate.

Although it is the same piece of land with the same productive capacity, the value of the asset, as reported on the balance sheet, falls as the Costa Rican colón depreciates. This decrease in the value of the company’s assets must be offset by a decrease in the stockholders’ equity for the balance sheet to balance. The loss is due simply to changes in exchange rates and not the underlying profitability of the company.

Economic Risk

Economic risk is the risk that a change in exchange rates will impact a business’s number of customers or its sales. Even a company that is not involved in international transactions can face this type of risk. Consider a company located in Mississippi that makes shirts using 100% US-grown cotton. All of the shirts are made in the United States and sold to retail outlets in the United States. Thus, all of the company’s expenses and revenues are in US dollars, and the company holds no assets outside of the United States.

Although this firm has no financial transactions involving international currency, it can be impacted by changes in exchange rates. Suppose the US dollar strengthens relative to the Vietnamese dong. This will allow US retail outlets to purchase more Vietnamese dong, and thus more shirts from Vietnamese suppliers, for the same amount of US dollars. Because of this, the retail outlets experience a drop in the cost of procuring the Vietnamese shirts relative to the shirts produced by the firm in Mississippi. The Mississippi company will lose some of its customers to these Vietnamese producers simply because of a change in the exchange rate.

Hedging

Just as companies may practice hedging techniques to reduce their commodity risk exposure, they may choose to hedge to reduce their currency risk exposure. The types of futures contracts that we discussed earlier in this chapter exist for currencies as well as for commodities. A company that knows that it will need Korean won later this year to purchase raw materials from a South Korean supplier, for example, can purchase a futures contract for Korean won.

While futures contracts allow companies to lock in prices today for a future commitment, these contracts are not flexible enough to meet the risk management needs of all companies. Futures contracts are standardized contracts. This means that the contracts have set sizes and maturity dates. Futures contracts for Korean won, for example, have a contract size of 125 million won. A company that needs 200 million won later this year would need to either purchase one futures contract, hedging only a portion of its needs, or purchase two futures contracts, hedging more than it needs. Either way, the company has remaining currency risk.

In this next section, we will explore some additional hedging techniques.

Forward Contracts

Suppose a company needs access to 200 million Korean won on March 1. In addition to a specified contract size, currency futures contracts have specified days on which the contracts are settled. For most currency futures contracts, this occurs on the third Wednesday of the month. If the company needed 125 million Korean won (the basic contract size) on the third Wednesday of March (the standard settlement date), the futures contract could be useful. Because the company needs a different number of Korean won on a different date from those specified in the standard contract, the futures contract is not going to meet the specific risk management needs of the company.

Another type of contract, the forward contract, can be used by this company to meet its specific needs. A forward contract is simply a contractual agreement between two parties to exchange a specified amount of currencies at a future date. A company can approach its bank, for example, saying that it will need to purchase 200 million Korean won on March 1. The bank will quote a forward rate, which is a rate specified today for the sale of currency on a future date, and the company and the bank can enter into a forward contract to exchange dollars for 200 million Korean won at the quoted rate on March 1.

Because a forward contract is a contract between two parties, those two parties can specify the amount that will be traded and the date the trade will occur. This contract is similar to your agreeing with a hotel that you will arrive on March 1 and rent a room for three nights at $200 per night. You are agreeing today to show up at the hotel on a future (specified) date and pay the quoted price when you arrive. The hotel agrees to provide you the room on March 1 and cannot change the price of the room when you arrive. With a forward contract, you are also agreeing that you will indeed make the purchase and you cannot change your mind; so, using the hotel room analogy, this would mean that the hotel will definitely charge your credit card for the agreed-upon $200 per night on March 1.

The forward contract is an individualized contract between the buyer and the seller; they are both under a contractual obligation to honor the contract. Because this contract is not standardized like the futures contract (so that it can be traded on an exchange), it can be tailored to the needs of the two parties. While the forward contract has the advantage of being fine-tuned to meet the company’s needs, it has a risk, known as counterparty risk, that the futures contract does not have. The forward contract is only as good as the promise of the counterparty. If the company enters into a forward contract to purchase 200 million Korean won on March 1 from its bank and the bank goes out of business before March 1, the company will not be able to make the exchange with a nonexistent bank. The exchanges on which futures contracts are traded guard the purchaser of a futures contract from this type of risk by guaranteeing the contract.

Natural Hedges

A hedge simply refers to a reduction in the risk or exposure that a company has to volatility and uncertainty. We have been focusing on how a company might use financial market instruments to hedge, but sometimes a company can use a natural hedge to mitigate risk. A natural hedge occurs when a business can offset its risk simply through its own operations. With a natural hedge, when a risk occurs that would decrease the value of a company, an offsetting event occurs within the firm that increases the value of the company.

As an example, consider a British-based travel agency. One of the major tours the company offers is a tour of Italy. The company arranges for transportation, lodging, meals, and sightseeing for Brits to visit the highlights of Rome, Florence, and Venice. Because the company charges customers in British pounds but must pay the bus companies, hotels, and other service providers in Italy in euros, the travel agency faces significant transaction exposure. If the value of the British pound depreciates after the company sets the price it will charge for the tour but before it pays the Italian suppliers, the company will be harmed. In fact, if the British pound depreciates by a great deal, the company could end up in a situation in which the British pounds it collects are not enough to purchase the euros it needs to pay its suppliers.

The company could create a natural hedge by offering tours of London to individuals living in the European Union. The travel agency could charge people who live in Germany, Italy, Spain, or any other country that has the euro as its currency for a travel package to London. Then the agency would pay British restaurants, tour guides, hotels, and bus companies in British pounds. This segment of the business also has currency risk. If the British pound depreciates, the company gains because the euros it collects from its EU customers will purchase more British pounds than before.

Thus, the company has created a situation in which if the British pound depreciates, the decrease in value of its tours of Italy is exactly offset by the increase in value of its tours of London. If the British pound appreciates, the opposite occurs: the company experiences a gain in its division that charges British pounds for tourists traveling to Italy and an offsetting loss in its division that charges euros for tourists traveling to London.

Options

A financial option gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to purchase or sell an asset for a specified price at some future date. Options are considered derivative securities because the value of a derivative is derived from, or comes from, the value of another asset.

Options Terminology

Specific terminology is used in the finance industry to describe the details of an options contract. If the owner of an option decides to purchase or sell the asset according to the terms of the options contract, the owner is said to be exercising the option. The price the option holder pays if purchasing the asset or receives if selling the asset is known as the strike price or exercise price. The price the owner of the option paid for the option is known as the premium.

An option contract will have an expiration date. The most common kinds of options are American options, which allow the holder to exercise the option at any time up to and including the expiration date. Holders of European options may exercise their options only on the expiration date. The labels American option and European option can be confusing as they have nothing to do with the location where the options are traded. Both American and European options are traded worldwide.

Option contracts are written for a variety of assets. The most common option contracts are options on shares of stock. Options are traded for US Treasury securities, currencies, gold, and oil. There are also options on agricultural products such as wheat, soybeans, cotton, and orange juice. Thus, options can be used by financial managers to hedge many types of risk, including currency risk, interest rate risk, and the risk that arises from fluctuations in the prices of raw materials.

Options are divided into two main categories, call options and put options. A call option gives the owner of the option the right, but not the obligation, to buy the underlying asset. A put option gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to sell the underlying asset.

Call Options

If a Korean company knows that it will need pay a $100,000 bill to a US supplier in six months, it knows how many US dollars it will need to pay the bill. As a Korean company, however, its bank account is denominated in Korean won. In six months, it will need to use its Korean won to purchase 100,000 US dollars.

The company can determine how many Korean won it would take to purchase $100,000 today. If the current exchange rate is

, then it will need KWN 110,000,000 to pay the bill. The current exchange rate is known as the spot rate.

The company, however, does not need the US dollars for another six months. The company can purchase a call option, which is a contract that will allow it to purchase the needed US dollars in six months at a price stated in the contract. This allows the company to guarantee a price for dollars in six months, but it does not obligate the company to purchase the dollars at that price if it can find a better price when it needs the dollars in six months.

The price that is in the contract is called the strike price (exercise price). Suppose the company purchases a call contract for US dollars with a strike price of KWN 1,200/USD. While this contract would be for a set size, or a certain number of US dollars, we will talk about this transaction as if it were per one US dollar to highlight how options contracts work.

The company must pay a price, known as the premium, to purchase this call option contract. For our example, let’s assume the premium for the call option contract is KWN 50. In other words, the company has paid KWN 50 for the right to buy US dollars in six months for a price of KWN 1,200/USD.

In six months, the company makes a choice to either (1) pay the strike price of KWN 1,200/USD or (2) let the option expire. If the company chooses to pay the strike price and purchase the US dollars, it is exercising the option. How does the company choose which to do? It simply compares the strike price of KWN 1,200/USD to the market, or spot, exchange rate at the time the option is expiring.

If, six months from now, the spot exchange rate is KWN 1,150 = USD 1, it will be cheaper for the company to buy the US dollars it needs at the spot price than it would be to buy the dollars with the option. In fact, if the spot rate is anything below KWN 1,200 = USD 1, the company will not choose to exercise the option. If, however, the spot exchange rate in six months is KWN 1,300 = USD 1, the company will exercise the option and purchase each US dollar for only KWN 1,200.

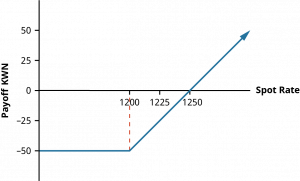

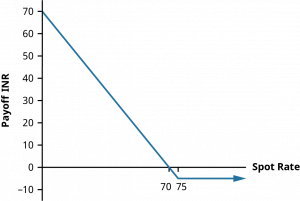

The profitability, or the payoff, to the owner of a call option is represented by the chart in Figure 12.4 below. Possible spot prices are measured from left to right, and the financial gain or loss to the company of the option contract is measured vertically. If the spot price is anything less than KWN 1,200/USD, the option expires without being exercised. The company paid KWN 50 for something that ended up being worthless.

If, in six months, the spot exchange rate is KWN 1,225 = USD 1, then the company will choose to exercise the option. The company will be saving KWN 25 for each dollar purchased, but the company originally paid 50 KWN for the contract. So, the company will be 25 KWN worse off than if it had never purchased the call option. If the spot exchange rate is KWN 1,250 = USD 1, the company will be in exactly the same position having purchased and exercised the call option as it would have been if it had not purchased the option. At any spot price higher than KWN 1,250/USD, the firm will be in a better financial position, or will have a positive payoff, because it purchased the call option. The more the Korean won depreciates over the next six months, the higher the payoff to the firm of owning the call contract. Purchasing the call contract is a way that the company can protect itself from the currency exposure it faces.

For any transaction, there must be two parties—a buyer and a seller. For the company to have purchased the call option, another party must have sold the call option. The seller of a call option is called the option writer. Let’s consider the potential benefits and risks to the writer of the call option.

When the company purchases the call option, it pays the premium to the writer. The writer of the option does not have a choice regarding whether the option will be exercised. The purchaser of the option has the right to make the choice; in essence, the writer of the option sold the right to make that decision to the purchasers of the call option.

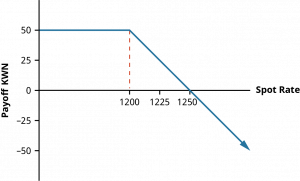

Figure 12.5 shows the payoff to the writer of the call option. Recall that the buyer of the call option will let the option expire if the spot rate is less than KWN1,200=USD1

when the call option matures in six months. If this occurs, the writer of the option collected the KWN 50 option premium when the contract was sold and then never hears from the purchaser again. This is what the writer of the option is hoping for; the writer of the call option profits when the options contract is not exercised

If the spot rate is above KWN 1,200 = USD 1, then the holder of the option will choose to exercise the right to purchase the won at the option strike price. Then the writer of the option will be obligated to sell the Korean won at a price of KWN 1,200/USD. If the spot rate is KWN 1,250 =USD 1, the option writer will be obligated to sell the dollars for KWN 50 less than what they are worth; because the option writer was initially paid a KWN 50 premium for taking on that obligation, the option writer will just break even. For any exchange rate higher than KWN 1,250 = USD 1, the writer of the call option will have a loss. The option contract is a zero-sum game. Any payoff the owner of the option receives is exactly equal to the loss the writer of the option has. Any loss the owner of the option has is exactly equal to the payoff the writer of the option receives.

Put Options

While the call option you just considered gives the owner the right to buy an underlying asset, the put option gives the owner to right to sell an underlying asset. Take, for example, an Indian company that has a contract to provide graphic artwork for a US company. The US company will pay the Indian company 200,000 US dollars in three months.

While the Indian company receives US dollars, it must pay its workers in Indian rupees. Because the company does not know what the spot exchange rate will be in three months, it faces transaction risk and may be interested in hedging this exposure using a put option.

The company knows that the current spot rate is INR 75 = USD 1, meaning that the company would be able to use $200,000 to purchase

if it possessed the $200,000 today. If the Indian rupee appreciates relative to the US dollar over the next three months, however, the company will receive fewer rupees when it makes the exchange; perhaps the company will not be able to purchase enough rupees to cover the wages of its employees.

Assume the company can purchase a put option that gives it the right to sell US dollars in three months at a strike price of INR 75/USD; the premium for this put option is INR 5. By purchasing this put option, the company is spending INR 5 to guarantee that it can sell its US dollars for rupees in three months at a price of INR 75/USD.

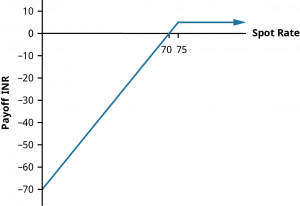

If, in three months, when the company receives payment in US dollars, the spot exchange rate is higher than INR 75 = USD 1, the company will simply exchange the US dollars for rupees at that exchange rate, allowing the put option to expire without exercising it. The payoff to the company for the option is INR -5, the premium that was paid for the option that was never used (see Figure 12.6).

If, however, in three months, the spot exchange rate is anything less than INR75 = USD1, then the company will choose to exercise the option. If the spot rate is between INR 70 = USD 1 and INR 75 = USD 1, the payoff for the option is negative. For example, if the spot exchange rate is INR 72 = USD 1, the company will exercise the option and receive three more Indian rupees per dollar than it would in the spot market. However, the company had to spend INR 5 for the option, so the payoff is INR -2. At a spot exchange rate of INR 70 = USD 1, the company has a zero payoff; the benefit of exercising the option, INR 5, is exactly equal to the price of purchasing the option, the premium of INR 5. If, in three months, the spot exchange rate is anything below INR 70 = USD 1, the payoff of the put option is positive. At the theoretical extreme, if the USD became worthless and would purchase no rupees in the spot market when the company received the dollars, the company could exercise its option and receive INR 75/USD, and its payoff would be INR 70.

Now that we have considered the payoff to a purchaser of a put contract, let’s consider the opposite side of the contract: the seller, or writer, of the put option. The writer of a put option is selling the right to sell dollars to the purchaser of the put option. The writer of the put option collects a premium for this. The writer of the put has no choice as to whether the put option will be exercised; the writer only has an obligation to honor the contract if the owner of the put option chooses to exercise it.

The owner of the option will choose to let the option expire if the spot exchange rate is anything above INR 75 = USD 1. If that is the case, the writer of the put option collects the INR 5 premium for writing the put, as shown by the horizontal line in Figure 12.7. This is what the writer of the put is hoping will occur.

The owner of the option will choose to exercise the option if the exchange rate is less than INR 75 = USD 1. If the spot exchange rate is between INR 70 = USD 1 and INR 75 = USD 1, the writer of the put option has a positive payoff. Although the writer must now purchase US dollars for a price higher than what the dollars are worth, the INR 5 premium that the writer received when entering into the position is more than enough to offset that loss. If the spot exchange rate drops below INR 70 = USD 1, however, the writer of the put option is losing more than INR 5 when the option is exercised, leaving the writer with a negative payoff. In the extreme, the writer of the put will have to purchase worthless US dollars for INR 75/USD, resulting in a loss of INR 70.

Notice that the payoff to the writer of the put is the negative of the payoff to the holder of the put at every spot price. The highest payoff occurs to the writer of the put when the option is never exercised. In that instance, the payoff to the writer is the premium that the holder of the put paid when purchasing the option (see Figure 12.7).

Table 12.2 provides a summary of the positions that the parties who enter into options contract are in. Remember that the buyer of an option is always the one purchasing the right to do something. The seller or writer of an option is selling the right to make a decision; the seller has the obligation to fulfill the contract should the buyer of the option choose to exercise the option. The most the seller of an option can ever profit is by the premium that was paid for the option; this occurs when the option is not exercised.

| Benefits | Harm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party to an Option Contract | Right of the Party | Obligation of the Party | When | Maximum Profit | When | Maximum Loss |

| Buyer of a call | To buy | Price of underlying rises | Unlimited | Price of underlying falls | Premium paid | |

| Seller of a call | To sell | Price of underlying falls | Premium received | Price of underlying rises | Unlimited | |

| Buyer of a put | To sell | Price of underlying falls | Strike price minus premium | Price of underlying rises | Premium paid | |

| Seller of a put | To buy | Price of underlying rises | Premium received | Price of underlying falls | Strike price minus premium | |

Footnotes

- 6Global Agricultural Information Network. Brazil: Coffee Annual 2019. GAIN Report No. BR19006. Washington, DC: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, May 2019. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Coffee%20Annual_Sao%20Paulo%20ATO_Brazil_5-16-2019.pdf

- 7Data from Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). “Brazil / US Foreign Exchange Rate (DEXBZUS).” FRED. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed August 6, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DEXBZUS

- 8Data from Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). “Japan / US Foreign Exchange Rate (DEXJPUS).” FRED. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed August 6, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DEXJPUS

Attribution:

This chapter is from “Principles of Finance” https://openstax.org/books/principles-finance/pages/1-why-it-matters by Dahlquist and Knight. This book is licensed under the CC-BY 4.0 license. 2022 OpenStax.