- Generate a forecasted income statement that incorporates pertinent sales, functional, and policy variables.

- Generate a forecasted balance sheet.

- Connect the balance sheet and income statement forecasts with appropriate feedback linkages.

39 Generating the Complete Forecast

Learning Objectives

In this section of the chapter, we will tie together what we have learned so far about forecasting sales, common-size analysis, and using what we know about the company and its environment to create a full set of pro forma (forward-looking or forecasted) financial statements.

Forecast the Income Statement

To arrive at a fully forecasted income statement, we use historical income statements, common-size income statements, and any additional information we have about future sales and costs, such as the effects of the economy and competition. As we saw earlier in the chapter, we begin with forecasted sales because they are the basis for many of the forecasted costs.

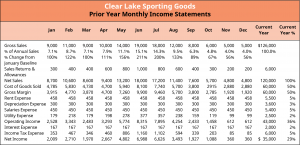

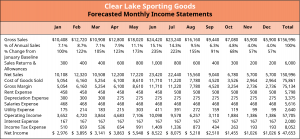

Let’s begin with the sales forecast for Clear Lake Sporting Goods that we saw earlier in the chapter, in Figure 4.9, and use it along with the prior year income statement by month shown in Figure 4.12. We will consider other data we have about the business to begin creating a full income statement (see Figure 4.13).

Rent is a fixed cost that historically amounts to $458 per month. However, we know that the landlord is increasing rent by $50 starting on July 1. Thus, we will forecast rent at the same fixed cost of $458 per month for the first six months and increase it to $508 per month for the second half of the year.

Depreciation, also a fixed cost, was historically $300 per month. However, we know that depreciation expense will go down by $25 beginning in April. Thus, we forecast depreciation at $300 for the first three months and at $275 for the last 9 months.

Salaries expense has historically been $450 per month. However, we know that the company is implementing a new compensation program on January 1 that will increase salaries expense by 4% ($18). Thus, we will forecast salaries for the whole year at $468.

Utilities expense seems to vary somewhat by sales from month to month, as shops are open longer hours during their busy season. However, the total utilities expense is not expected to change for the coming year. Thus, the forecast for utilities expense remains at $2,500, broken down by month as a percentage of sales.

Interest expense is a fixed cost and isn’t anticipated to change. Thus, the same $167 interest expense per month is forecast for the coming year.

Finally, income tax expense is forecasted as a percentage of operating income because tax liability is incurred as a direct result of operating income. Figure 4.13 shows the next 12 months’ forecast for Clear Lake Sporting Goods using all of this data.

Forecast the Balance Sheet

Now that we have a reasonable income statement forecast, we can move on to the balance sheet. The balance sheet, however, is entirely different from the income statement. It requires a bit more research and additional assumptions. Just like the income statement, it’s often a work in progress. A first draft is a good starting point, but adjustments must be made once it is created, and all the interrelationships between the statements, cash flow in particular, are taken into consideration.

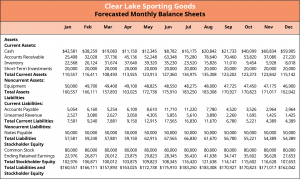

The balance sheet is a bit more difficult to forecast because the statement reflects balances at just a given point in time. Account balances change daily, so forecasting just one snapshot in time for each month can be a challenge. A good starting point is to assess general company financial policies or rules of thumb. For example, assume that Clear Lake pays most of its vendors on net 30-day terms. A good way to forecast accounts payable on the balance sheet might be to add up the cost of goods sold from the forecasted income statement for the prior month. For example, in Figure 4.14, we see that Clear Lake has forecasted its accounts payable for March as the cost of goods sold in March from its forecasted income statement.

For accounts receivable, Clear Lake generally receives payment from customers within net 90-day terms. Thus, it uses the sum of the current and prior two months’ forecasted sales to estimate its accounts receivable balance.

Inventory will vary throughout the year. For the first six months, the company tries to build inventory for four months of sales. Once the busy season hits, inventory goes down to three months’ worth of future sales, then finally drops to only two months of sales in December. Thus, managers use their sales forecast by month to estimate their inventory ending balance each month.

The equipment balance is forecasted by reducing the prior month’s balance by the forecasted depreciation expense on the forecasted income statement.

Unearned revenue is historically around 50% of the current month’s sales. Thus, Clear Lake estimates its unearned revenue balance each month by taking the current month’s net sales from the forecasted income statement and multiplying it by 50%.

Short-term investments, notes payable, and common stock are not anticipated to change, so the current balance is forecasted to remain the same for the next 12 months.

To forecast the ending balance for retained earnings for each month, managers add the monthly net income from the forecasted balance sheet to the prior balance and subtract a quarterly $10,000 dividend.

Once all of these accounts are completed, the balance sheet is out of balance. Given that all of these events are somewhat related but are not tied together dollar for dollar, it’s not surprising when the forecasted balance sheet is finished and does not balance. To complete the first draft (see Figure 4.14), the cash account is used as a variable and plugged in to make the balance sheet balance. Notice that by the end of the year, the company has $59,905 in cash. However, look at what happens midyear—the cash account falls to only $8,782. In the next section, we will generate a cash flow forecast, which will allow Clear Lake to update its balance sheet forecast once it estimates what it will do to cover the cash flow gaps.

Linkages between the Forecasted Balance Sheet and the Income Statement

Notice that in the discussion in the prior section on the balance sheet forecast, a lot of the information in the forecasted income statement was used to generate the forecasted balance sheet. The balance sheet accounts generally depend on activity reported in the income statement. For example, for many firms, the balance in their accounts receivable account is tied to their sales. Looking at historical balances in the accounts receivable account and how those relate to historical sales will help determine how to use the forecasted future sales to estimate the future balance of accounts receivable.

The same is true of accounts payable. Looking at past balances, past expenses (normally cost of goods sold), and the firm’s payment terms for its vendors allows managers to use forecasted cost of goods sold or other expenses to estimate the balance in the accounts payable account.

We learned in Financial Statements that net income flows into retained earnings. Thus, the net income from the forecasted income statement can be used to help estimate the ending balance in retained earnings. If the firm intends to issue any dividends in the coming year, managers should also estimate that reduction in their forecast.

It’s also common to find other general policies or procedures that help drive performance and aid in forecasting balances. For example, if the company has a goal of maintaining a certain level of inventory or a minimum balance in its cash account, that information can be used to guide the estimate for those accounts.

Attribution:

This chapter is from “Principles of Finance” https://openstax.org/books/principles-finance/pages/1-why-it-matters by Dahlquist and Knight. This book is licensed under the CC-BY 4.0 license. 2022 OpenStax.