24 2.6 Mineral Properties — Physical Geology – 2nd Edition

Streak

In the context of minerals, “colour” is what you see when light reflects off the surface of the sample. One reason that colour can be so variable is that the type of surface is variable. It may be a crystal face or a fracture surface or a cleavage plane, and the crystals may be large or small depending on the nature of the rock. If we grind a small amount of the sample to a powder we get a much better indication of its actual colour. This can easily be done by scraping a corner of the sample across a streak plate (a piece of unglazed porcelain) to make a streak. The result is that some of the mineral gets ground to a powder and we can get a better impression of its “true” colour (Figure 2.6.2).

Lustre

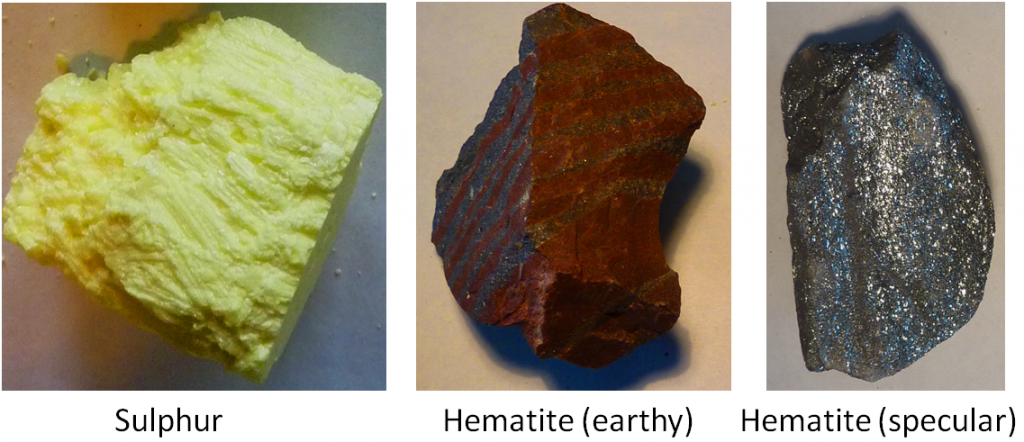

Lustre is the way light reflects off the surface of a mineral, and the degree to which it penetrates into the interior. The key distinction is between metallic and non-metallic lustres. Light does not pass through metals, and that is the main reason they look “metallic.” Even a thin sheet of metal—such as aluminum foil—will not allow light to pass through it. Many non-metallic minerals may look as if light will not pass through them, but if you take a closer look at a thin edge of the mineral you can see that it does. If a non-metallic mineral has a shiny, reflective surface, then it is called “glassy.” If it is dull and non-reflective, it is “earthy.” Other types of non-metallic lustres are “silky,” “pearly,” and “resinous.” Lustre is a good diagnostic property since most minerals will always appear either metallic or non-metallic. There are a few exceptions to this (e.g., hematite in Figure 2.6.1).

Hardness

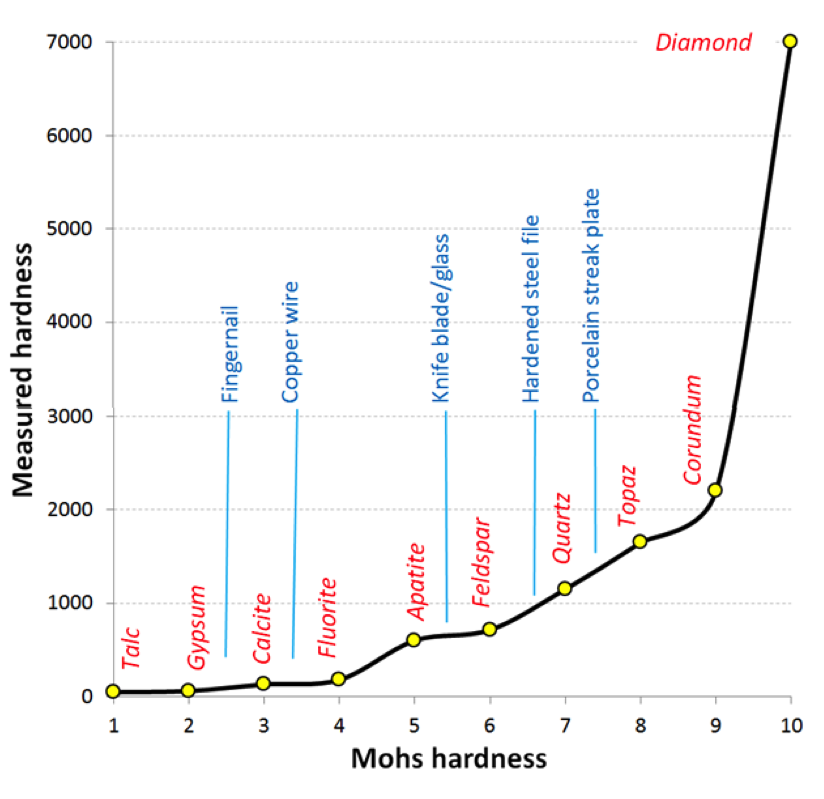

One of the most important diagnostic properties of a mineral is its hardness. In 1812 German mineralogist Friedrich Mohs came up with a list of 10 reasonably common minerals that had a wide range of hardnesses. These minerals are shown in Figure 2.6.3, with the Mohs scale of hardness along the bottom axis. In fact, while each mineral on the list is harder than the one before it, the relative measured hardnesses (vertical axis) are not linear. For example apatite is about three times harder than fluorite and diamond is three times harder than corundum. Some commonly available reference materials are also shown on this diagram, including a typical fingernail (2.5), a piece of copper wire (3.5), a knife blade or a piece of window glass (5.5), a hardened steel file (6.5), and a porcelain streak plate (7). These are tools that a geologist can use to measure the hardness of unknown minerals. For example, if you have a mineral that you can’t scratch with your fingernail, but you can scratch with a copper wire, then its hardness is between 2.5 and 3.5. And of course the minerals themselves can be used to test other minerals.

Crystal Habit

When minerals form within rocks, there is a possibility that they will form in distinctive crystal shapes if they formed slowly and if they are not crowded out by other pre-existing minerals. Every mineral has one or more distinctive crystal habits, but it is not that common, in ordinary rocks, for the shapes to be obvious. Quartz, for example, will form six-sided prisms with pointed ends (Figure 2.6.4a), but this typically happens only when it crystallizes from a hot water solution within a cavity in an existing rock. Pyrite can form cubic crystals (Figure 2.6.4b), but can also form crystals with 12 faces, known as dodecahedra (“dodeca” means 12). The mineral garnet also forms dodecahedral crystals (Figure 2.6.4c).

Because well-formed crystals are rare in ordinary rocks, habit isn’t as useful a diagnostic feature as one might think. However, there are several minerals for which it is important. One is garnet, which is common in some metamorphic rocks and typically displays the dodecahedral shape. Another is amphibole, which forms long thin crystals, and is common in igneous rocks like granite (Figure 1.4.2).

Mineral habit is often related to the regular arrangement of the molecules that make up the mineral. Some of the terms that are used to describe habit include bladed, botryoidal (grape-like), dendritic (branched), drusy (an encrustation of minerals), equant (similar in all dimensions), fibrous, platy, prismatic (long and thin), and stubby.

Cleavage and Fracture

Crystal habit is a reflection of how a mineral grows, while cleavage and fracture describe how it breaks. Cleavage and fracture are the most important diagnostic features of many minerals, and often the most difficult to understand and identify. Cleavage is what we see when a mineral breaks along a specific plane or planes, while fracture is an irregular break. Some minerals tend to cleave along planes at various fixed orientations, some do not cleave at all (they only fracture). Minerals that have cleavage can also fracture along surfaces that are not parallel to their cleavage planes.

As we’ve already discussed, the way that minerals break is determined by their atomic arrangement and specifically by the orientation of weaknesses within the lattice. Graphite and the micas, for example, have cleavage planes parallel to their sheets (Figures 2.2.5 and 2.4.5), and halite has three cleavage planes parallel to the lattice directions (Figure 2.2.6).

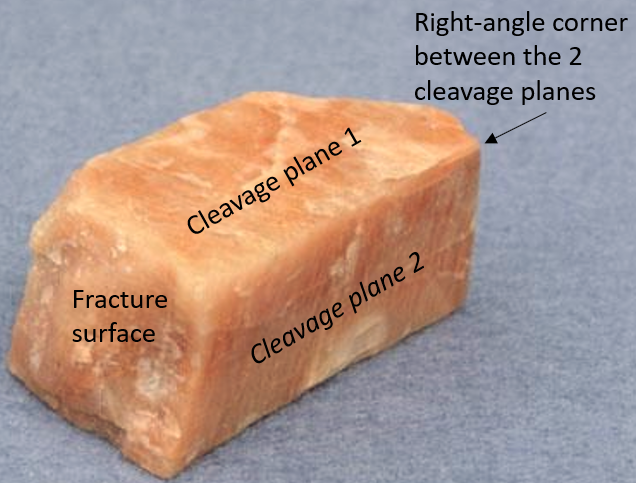

Quartz has no cleavage because it has equally strong Si–O bonds in all directions, and feldspar has two cleavages at 90° to each other (Figure 2.6.5).

One of the main difficulties with recognizing and describing cleavage is that it is visible only in individual crystals. Most rocks have small crystals and it’s very difficult to see the cleavage within those crystals. Geology students have to work hard to understand and recognize cleavage, but it’s worth the effort since it is a reliable diagnostic property for most minerals.

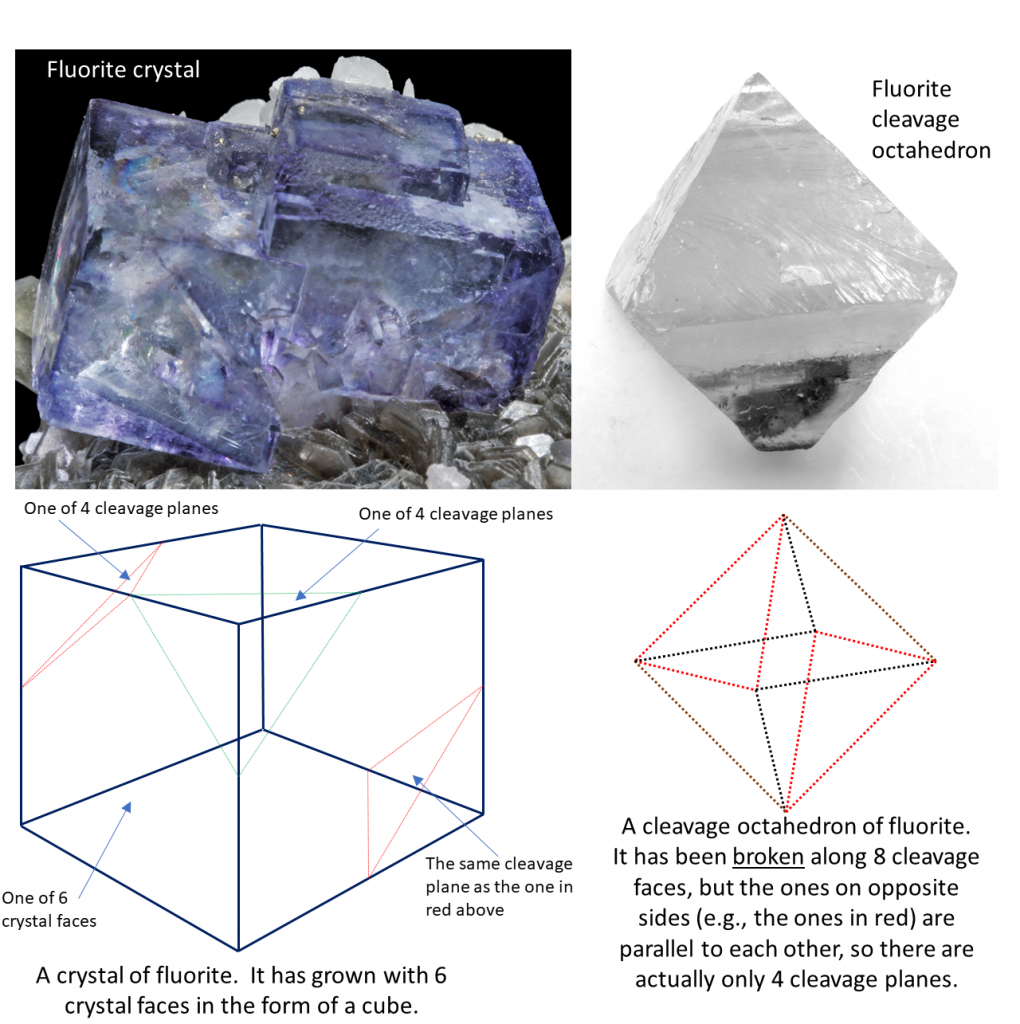

One last thing: it is important to recognize the difference between cleavage planes and crystal surfaces. As already noted, crystal surfaces are related to how a mineral grows while cleavage planes are related to how it breaks. In most minerals cleavage planes and crystal surfaces do not align with one-another. An exception is halite, which grows in cubic crystals and has cleavage along those same planes (Figure 1.4.1 and 2.2.6). But this doesn’t hold for most minerals. Quartz has crystal surfaces but no cleavage at all. Fluorite forms cubic crystals like those of halite, but it cleaves along planes that differ in orientation from the crystal surfaces. This is illustrated in Figure 2.6.6.

Density

Density is a measure of the mass of a mineral per unit volume, and it is a useful diagnostic tool in some cases. Most common minerals, such as quartz, feldspar, calcite, amphibole, and mica, have what we call “average density” (2.6 to 3.0 grams per cubic centimetre (g/cm3)), and it would be difficult to tell them apart on the basis of their density. On the other hand, many of the metallic minerals, such as pyrite, hematite, and magnetite, have densities over 5 g/cm3. They can easily be distinguished from the lighter minerals on the basis of density, but not necessarily from each other. A limitation of using density as a diagnostic tool is that one cannot assess it in minerals that are a small part of a rock that is mostly made up of other minerals.

Other Properties

Several other properties are also useful for identification of some minerals. For example, calcite is soluble in dilute acid and will give off bubbles of carbon dioxide. Magnetite is magnetic, so will affect a magnet. A few other minerals are weakly magnetic.

Image Descriptions

| Talc | Gypsum | Calcite | Fluorine | Apatite | Feldspar | Quartz | Topaz | Corundum | Diamond | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Hardness | 50 | 60 | 105 | 200 | 659 | 700 | 1100 | 1648 | 2085 | 7000 |

| Mohs Hardness | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.6.2: © Karla Panchuk. CC BY.

- Figure 2.6.4a: Quartz Bresil © Didier Descouens. CC BY.

- Figure 2.6.4b: Pyrite cubic crystals on marlstone © Carles Millan. CC BY-SA.

- Figure 2.6.4c: Almandine garnet © Eurico Zimbres (FGEL/UERJ) and Tom Epaminondas (mineral collector). CC BY-SA.

<!– pb_fixme –>

<!– pb_fixme –>