133 18.4 Ocean Water — Physical Geology – 2nd Edition

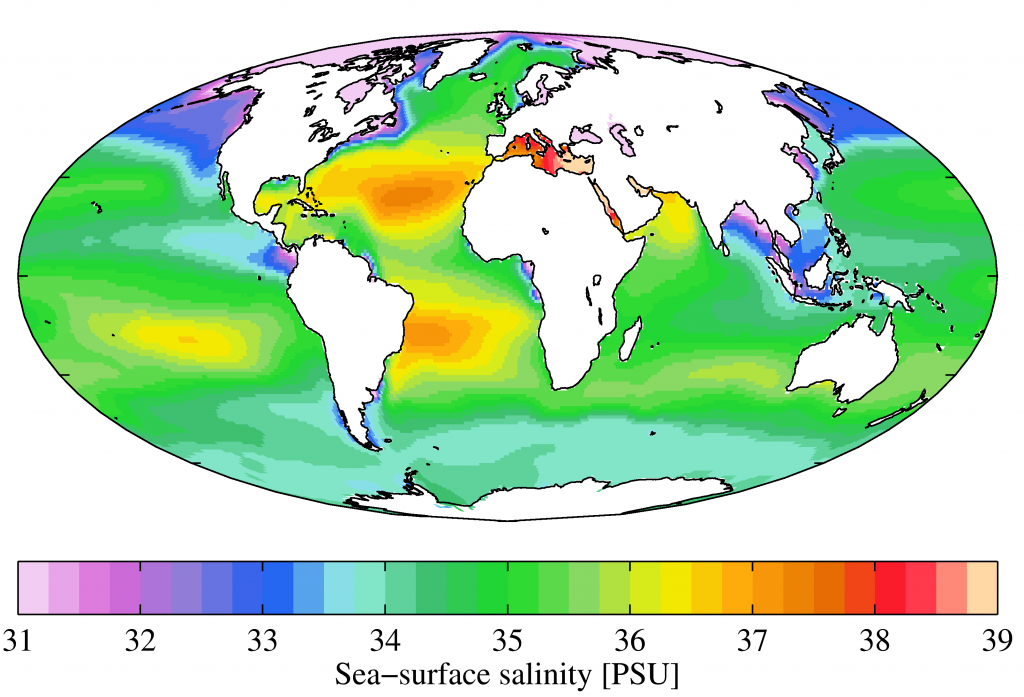

The average salinity of the oceans is 35 g of salt per litre of water, but there are significant regional variations in this value, as shown in Figure 18.4.2. Ocean water is least salty (around 31 g/L) in the Arctic, and also in several places where large rivers flow in (e.g., the Ganges/Brahmaputra and Mekong Rivers in southeast Asia, and the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in China). Ocean water is most salty (over 37 g/L) in some restricted seas in hot dry regions, such as the Mediterranean and Red Seas. You might be surprised to know that, in spite of some massive rivers flowing into it (such as the Nile and the Danube), water does not flow out of the Mediterranean Sea into the Atlantic. There is so much evaporation happening in the Mediterranean basin that water flows into it from the Atlantic, through the Strait of Gibraltar.

In the open ocean, salinities are elevated at lower latitudes because this is where most evaporation takes place. The highest salinities are in the subtropical parts of the Atlantic, especially north of the equator. The northern Atlantic is much more saline than the north Pacific because the Gulf Stream current brings a massive amount of salty water from the tropical Atlantic and the Caribbean to the region around Britain, Iceland, and Scandinavia. The salinity in the Norwegian Sea (between Norway and Iceland) is substantially higher than that in other polar areas.

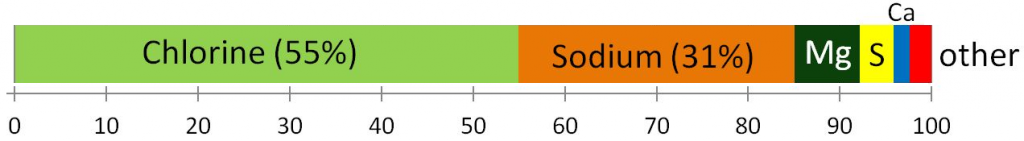

How salty is the sea? If you’ve ever had a swim in the ocean, you’ve probably tasted it. To understand how salty the sea is, start with 250 mL of water (1 cup). There is 35 g of salt in 1 L of seawater so in 250 mL (1/4 litre) there is 35/4 = 8.75 or ~9 g of salt. This is just short of 2 teaspoons, so it would be close enough to add 2 level teaspoons of salt to the cup of water. Then stir until it’s dissolved. Have a taste!

Of course, if you used normal refined table salt, then what you added was almost pure NaCl. To get the real taste of seawater you would want to use some evaporated seawater salt (a.k.a. sea salt), which has a few percent of magnesium, sulphur, and calcium plus some trace elements.

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 18.4 answers.

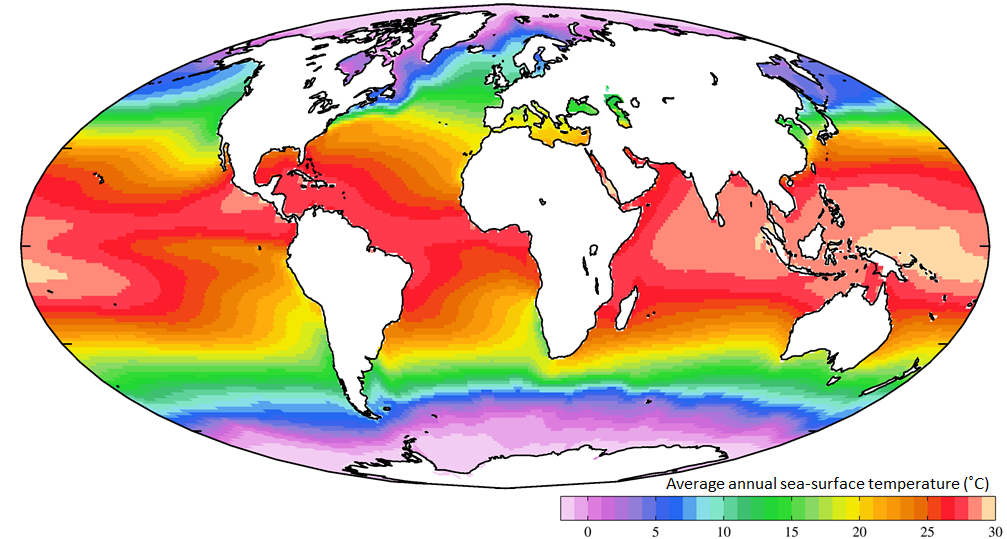

Not unexpectedly, the oceans are warmest near the equator—typically 25° to 30°C—and coldest near the poles—around 0°C (Figure 18.4.4). (Sea water will remain unfrozen down to about -2°C.) At southern Canadian latitudes, average annual water temperatures are in the 10° to 15°C range on the west coast and in the 5° to 10°C range on the east coast. Variations in sea-surface temperatures (SST) are related to redistribution of water by ocean currents, as we’ll see below. A good example of that is the plume of warm Gulf Stream water that extends across the northern Atlantic. St. John’s, Newfoundland, and Brittany in France are at about the same latitude (47.5° N), but the average SST in St. John’s is a frigid 3°C, while that in Brittany is a reasonably comfortable 15°C.

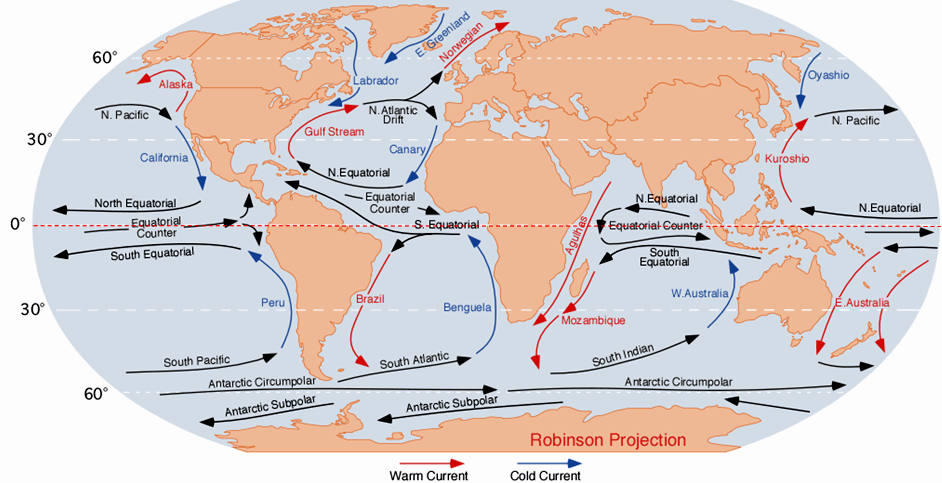

Currents in the open ocean are created by wind moving across the water and by density differences related to temperature and salinity. An overview of the main ocean currents is shown in Figure 18.4.5. As you can see, the northern hemisphere currents form circular patterns (gyres) that rotate clockwise, while the southern hemisphere gyres are counter-clockwise. This happens for the same reason that the water in your northern hemisphere sink rotates in a clockwise direction as it flows down the drain; this is caused by the Coriolis effect.

Because the ocean basins aren’t like bathroom basins, not all ocean currents behave the way we would expect. In the North Pacific, for example, the main current flows clockwise, but there is a secondary current in the area adjacent to our coast—the Alaska Current—that flows counter-clockwise, bringing relatively warm water from California, past Oregon, Washington, and B.C. to Alaska. On Canada’s eastern coast, the cold Labrador Current flows south past Newfoundland, bringing a stream of icebergs past the harbour at St. John’s (Figure 18.4.7). This current helps to deflect the Gulf Stream toward the northeast, ensuring that Newfoundland stays cool, and western Europe stays warm.

The Coriolis effect has to do with objects that are moving in relation to other objects that are rotating. An ocean current is moving across the rotating Earth, and its motion is controlled by the Coriolis effect.

Imagine that you are standing on the equator looking straight north and you fire a gun in that direction. The bullet in the gun starts out going straight north, but it also has a component of motion toward the east that it gets from Earth’s rotation, which is 1,670 kilometres per hour at the equator. Because of the spherical shape of Earth, the speed of rotation away from the equator is not as fast as it is at the equator (in fact, the Earth’s rotational speed is 0 kilometres per hour at the poles) so the bullet actually traces a clockwise curved path across Earth’s surface, as shown by the red arrow on the diagram. In the southern hemisphere the Coriolis effect is counterclockwise (green arrow).

The Coriolis effect is imparted to the rotations of ocean currents and tropical storms. If Earth were a rotating cylinder, instead of a sphere, there would be no Coriolis effect.

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 18.5 answers.

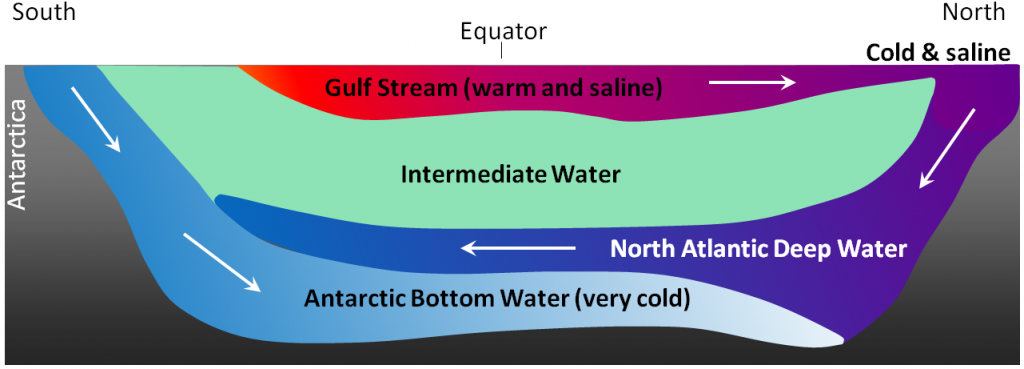

The currents shown in Figure 18.4.5 are all surface currents, and they only involve the upper few hundred metres of the oceans. But there is much more going on underneath. The Gulf Stream, for example, which is warm and saline, flows past Britain and Iceland into the Norwegian Sea (where it becomes the Norwegian Current). As it cools down, it becomes denser, and because of its high salinity, which also contributes to its density, it starts to sink beneath the surrounding water (Figure 18.4.8). At this point, it is known as North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW), and it flows to significant depth in the Atlantic as it heads back south. Meanwhile, at the southern extreme of the Atlantic, very cold water adjacent to Antarctica also sinks to the bottom to become Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) which flows to the north, underneath the NADW.

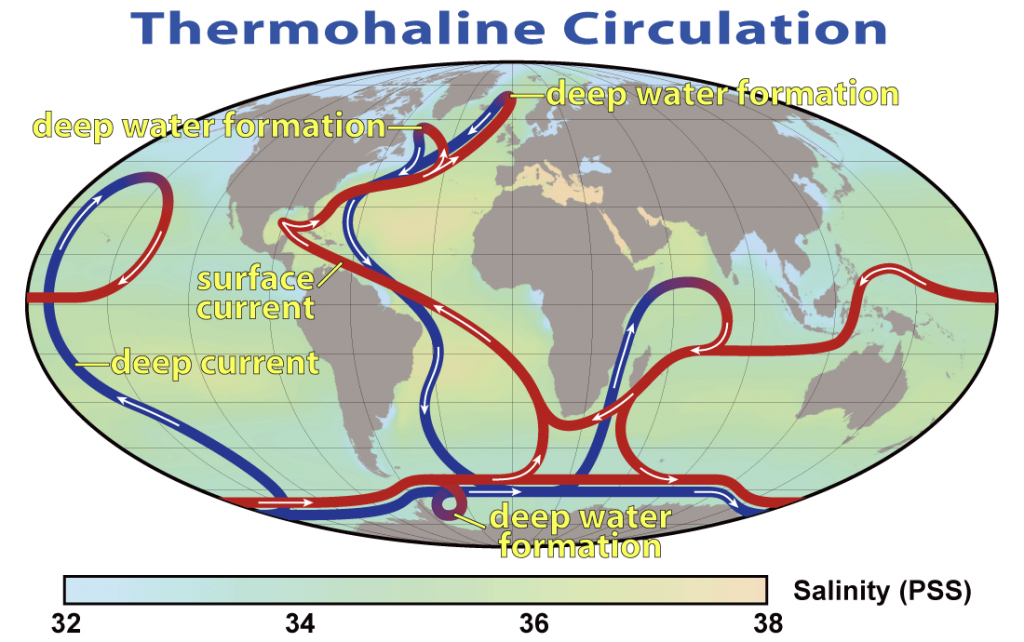

The descent of the dense NADW is just one part of a global system of seawater circulation, both at surface and at depth, as illustrated in Figure 18.4.9. The water that sinks in the areas of deep water formation in the Norwegian Sea and adjacent to Antarctica moves very slowly at depth. It eventually resurfaces in the Indian Ocean between Africa and India, and in the Pacific Ocean, north of the equator.

The thermohaline circulation is critically important to the transfer of heat on Earth. It brings warm water from the tropics to the poles, and cold water from the poles to the tropics, thus keeping polar regions from getting too cold and tropical regions from getting too hot. A reduction in the rate of thermohaline circulation would lead to colder conditions and enhanced formation of sea ice at the poles. This would start a positive feedback process that could result in significant global cooling. There is compelling evidence to indicate that there were major changes in thermohaline circulation, corresponding with climate changes, during the Pleistocene Glaciation.

Image Descriptions

Figure 18.4.5 image description: The currents of the world’s oceans work together to form a number of general patterns. Currents flow into each other to form larger currents. Groups of currents in the northern hemisphere flow clockwise. This includes groups of currents in the North Pacific Ocean and the North Atlantic Ocean. Currents in the southern hemisphere flow counter-clockwise. This includes groups of currents in the South Pacific Ocean, the South Atlantic Ocean, and the Indian Ocean. Currents flowing towards the equator are colder than the surrounding water. Currents flowing away from the equator are warmer than the surrounding water. Currents below 60° South flow from east to west (or west to east) around Antarctica. Currents along the Equator also flows east to west (or west to east). Currents flowing from east to west (or west to east) are the same temperature as the surrounding water. For a more detailed description of specific currents, refer to the following table, which describes 26 major currents, including their location, direction of flow, and relationship to surrounding currents. They are arranged in alphabetical order. Or, you can [Return to Figure 18.4.5].

| Name of Current | Temperature of current compared to the surrounding water | Direction of flow | Relationship to nearby currents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agulhas | A warm current | The Agulhas current flows south from the Arabian peninsula down the east coast of Africa. | The Agulhas current joins with the Mozambique current, which also flows south. |

| Alaska | A warm current | The Alaska current flows north up the west coast of the United States and Canada before circling to the west once it reaches Alaska | The Alaska current flows into the Oyashio current |

| Antarctic Circumpolar | No temperature difference | The Antarctic Circumpolar current flows east to circle around Antarctica. | The Antarctic Circumpolar flows east above the Antarctic Subpolar, which flows west. |

| Antarctic Subpolar | No temperature difference | The Antarctic Subpolar current flows west along the coast of Antarctica. | The Antarctic Subpolar current flows west below the Antarctic Circumpolar current, which flows east. |

| Benguela | A cold current | The Benguela current flows north along the south west coast of Africa. | The Benguela current flows into the South Equatorial current and is fed by the South Atlantic current. |

| Brazil | A warm current | The Brazil current flows south along the east coast of South America. | The Brazil current flows into the South Atlantic current and is fed by the south branch of the South Equatorial current. |

| California | A cold current | The California current flows south from the southwest coast of the United States down along the west coast of Mexico. | The California current flows into the North Equatorial current and is fed by the North Pacific current. |

| Canary | A cold current | The Canary current flows from south along the north west coast of Africa from Morocco to Sengal. | The Canary current flows into the North Equatorial current and is fed by the North Atlantic Drift. |

| East Australian | A warm current | The East Australian currents flow from the equator and south, past the east coast of Australia. One flows between New Zealand and Australia, and the other flows past the east side of New Zealand. | The East Australian currents flow into the South Pacific current and they are fed by the South Equatorial current. |

| East Greenland | A cold current | The East Greenland current flows south along the east coast of Greenland. | The East Greenland current flows into the Labrador current. |

| Equatorial Counter | No temperature difference. | The Equatorial Counter current flows east along the equator. It is broken up into three sections: One in the Pacific Ocean, one in the Atlantic Ocean, and one in the Indian Ocean. | The Equatorial Counter current flows east between the North Equatorial and the South Equatorial currents, which both flow west. |

| Gulf Stream | A warm current | The Gulf Stream flows north from the Caribbean along the east coast of the United States. | The Gulf Stream flows into the North Atlantic Drift current and is fed by the North Equatorial current. |

| Kuroshio | A warm current | The Kuroshio current flows north along the east coast of the Philippines and Japan. | The Kuroshio current flows into the North Pacific current and is fed by the North Equatorial current. |

| Labrador | A cold current | The Labrador current flows south along the eastern coast of Canada to the northern United States. | The Labrador current is partially fed by the East Greenland current. Once it reaches the northern United States, it flows past the Gulf Stream. |

| Mozambique | A warm current | The Mozambique current flows south along the east coast of Madagascar and into the Southern Ocean. | The Mozambique current flows into the South Indian current and is fed by the South Equatorial current. |

| North Atlantic Drift | No temperature difference | The North Atlantic Drift current flows east across the Atlantic Ocean from the north coast of the United States to the south coast of Spain. | The North Atlantic Drift current splits to flow north into the Norwegian current and to flow south into the Canary current. It is fed by the Gulf Stream. |

| North Equatorial | No temperature difference. | The North Equatorial current flows west just above the equator. It is broken up into three sections: One in the Pacific Ocean, one in the Atlantic Ocean, and one in the Indian Ocean. | The North Equatorial current in the Pacific Ocean flows into the Kuroshio current and is fed by the California current. The North Equatorial current in the Atlantic Ocean flows into the Gulf Stream and is fed by the Canary current. The North Equatorial current in the Indian Ocean turns at Africa to join the Equatorial Counter current. |

| North Pacific | No temperature difference | The North Pacific current flows west across the Pacific Ocean from Japan to the south coast of the United States. | The North Pacific current flows into the California current and is fed by the Kuroshio current. |

| Norwegian | A warm current | The Norwegian current flows north from the north coast of the United Kingdom to along the coast of Norway. | This current is fed by the northern branch of the North Atlantic Drift current and flows into the Arctic Ocean. |

| Oyashio | A cold current | The Oyashio current flows south along the east coast of Russia. | The Oyashio current clashes with the Kuroshio current, which flows north into the North Pacific current. |

| Peru | A cold current | The Peru current flows north along the central west coast of South America. | The Peru current flows into the South Equatorial current and is fed by the South Pacific current. |

| South Atlantic | No temperature difference | The South Atlantic current flows from the south tip of South America to towards the south tip of Africa. | The South Atlantic current flows into the Benguela current and is fed by the Brazil current. |

| South Equatorial | No temperature difference | The South Equatorial current flows west just below the equator. It is broken up into three sections: One in the Pacific Ocean, one in the Atlantic Ocean, and one in the Indian Ocean. | The South Equatorial current in the Pacific Ocean flows into the East Australian currents and is fed by the Peru current. The South Equatorial current in the Atlantic Ocean flows north and south: North along the north east coast of South America and south into the Brazil current. It is fed by the Benguela current. The South Equatorial current in the Indian Ocean flows into the Mozambique current and is fed by the West Australian current. |

| South Indian | No temperature difference | The South Indian current flows from the southern part of the Indian ocean towards the south west coast of Australia. | The South Indian current flows into the West Australian current and is fed by the Mozambique current. |

| South Pacific | No temperature difference | The South Pacific current flows east from the south east coast of Australia to the south west coast of South America. | The South Pacific current flows into the Peru current and is fed by the East Australian current. |

| West Australian current | A cold current | The West Australian current flows north along the west coast of Australia. | The West Australian current flows into the South Equatorial current and is fed by the South Indian current. |

Media Attributions

- Figure 18.4.1: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 18.4.2: “WOA09 sea-surf SAL AYool” © Plumbago. CC BY-SA.

- Figure 18.4.3: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 18.4.4: “WOA09 sea-surf TMP AYool” © Plumbago. CC BY-SA.

- Figure 18.4.5: “Corrientes Oceanicas” by Dr. Michael Pidwirny. Public domain.

- Figure 18.4.6: “Newfoundland Iceberg just off Exploits Island” © Shawn. CC BY-SA.

- Figures 18.4.7, 18.4.7: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 18.4.9: “Thermohaline Circulation” by NASA. Public domain.

<!– pb_fixme –>

<!– pb_fixme –>