2 Europe and Africa

This chapter of our story is bracketed by two population disasters. It begins in the 14th century with the Black Death and ends with the American depopulation of the Columbian Exchange, which we’ll talk about next time.

Nations and Empires

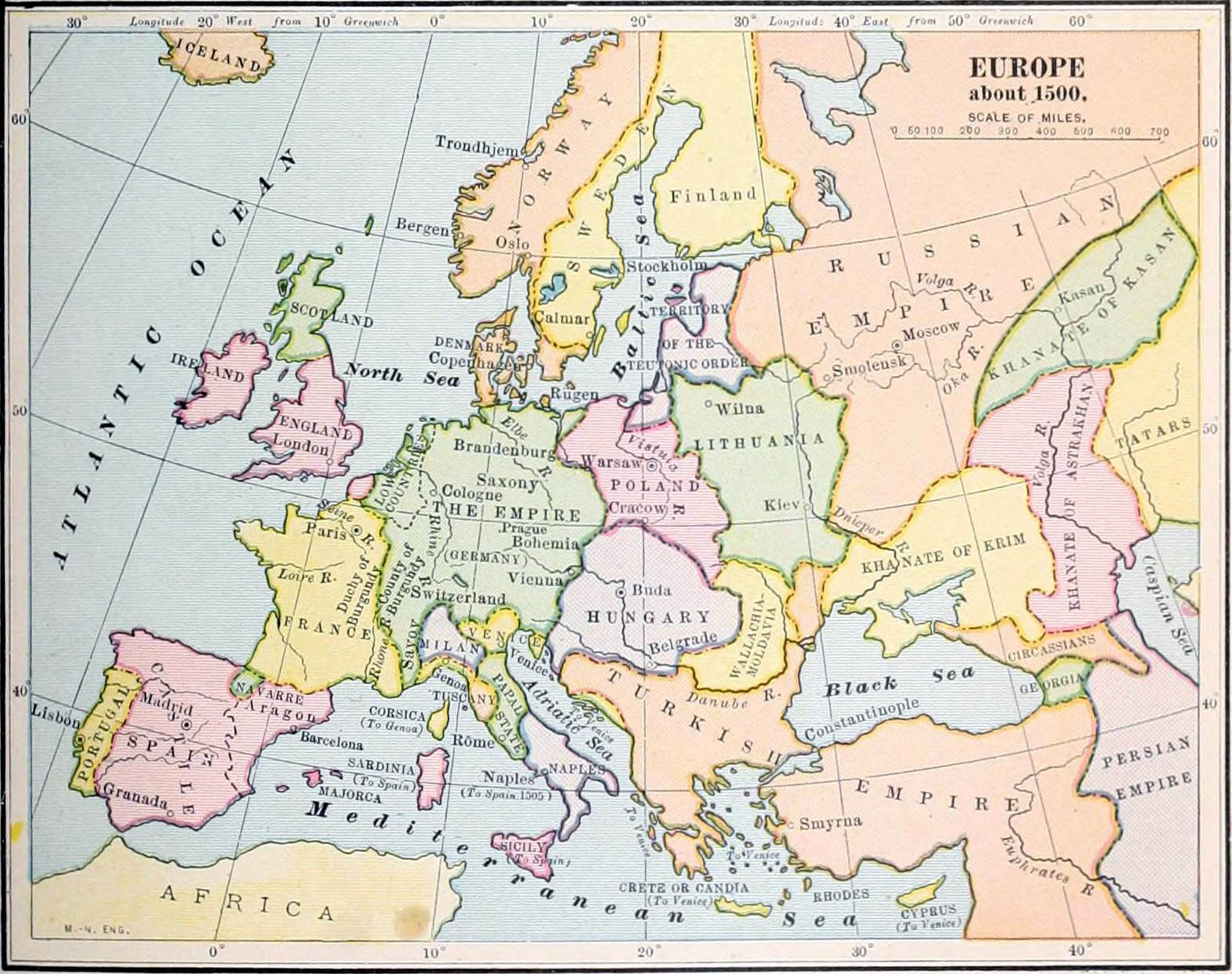

One of the major changes in Europe in the early modern period, which we take for granted today, is the beginning of a tendency toward nations rather than empires. Although some European rulers like Napoleon, Queen Victoria, and later Hitler tried to expand the scale of their realms into empires, these were exceptions that proved the rule (and Victoria’s British Empire was outside Europe). Europe’s nations were identified by factors like ethnicity, language, customs, and religion. Often these nations fought neighbors that were defined by different identities. This made European nations unlike the empires of Asia and the near east that typically included wide varieties of cultures and ethnicities within their borders.

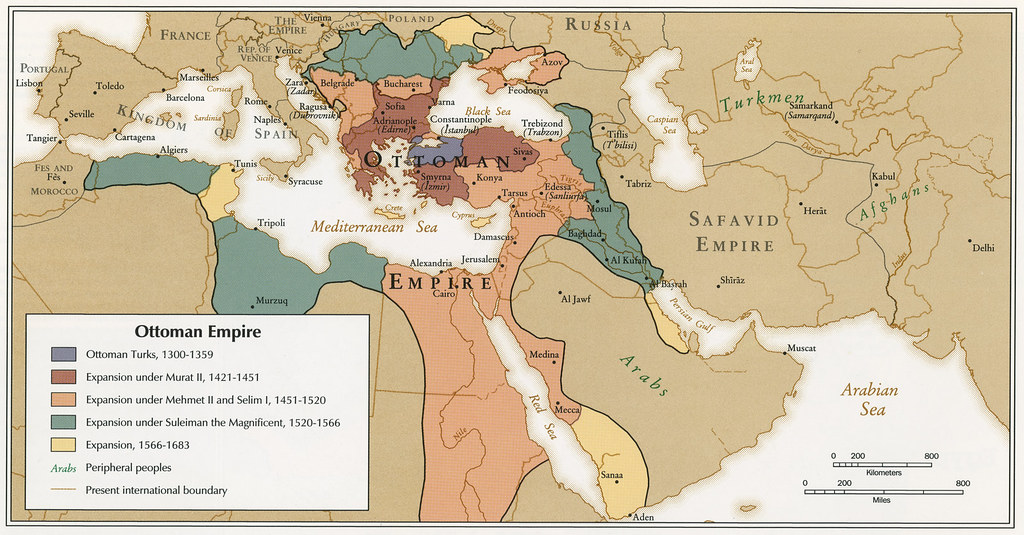

The first, oldest, and largest Asian empire was China, as we’ve already discussed. But there were four additional empires that set the scene for the early modern period, and whose histories helped shape the world today. These were the Mughal Empire in India, the Safavid Empire in Persia (Iran), the Russian Empire on Europe’s eastern border, and the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East. The Ottomans were a Muslim dynasty that rose on the borders of the Byzantine Empire in the 1300s and became a world power when Sultan Mehmed II (called Mehmed the Conqueror) overwhelmed the defenders of Constantinople in 1453.

Constantinople had been the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire) since the Emperor Constantine had moved his government there in 330 CE. The city was strategically important because it controlled the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits that connected the Mediterranean Sea with the Black Sea. This made it the gateway between Europe and Asia. Mehmed took the city as his new capital and renamed it Istanbul. The Sultan allowed Christians and Jews to continue living in Istanbul and granted the Eastern Orthodox Church autonomy as long as they accepted Ottoman authority. But many Christian refugees fled the city and found their ways to cities like Venice and Florence, where they helped ignite the period known as the Renaissance.

Istanbul quickly became the largest Eurasian city outside China. Under Sultans like Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566), the Ottomans expanded into Europe and nearly captured Vienna in 1529 and again in 1683. They controlled shipping in the western Mediterranean and the trade routes and major markets connecting to the Silk Road such as Cairo and Baghdad. The high cost of doing business in the Ottoman-controlled Middle East created an incentive for European merchants to seek other ways of reaching Asia. The Ottomans were actually quite tolerant of ethnic, language, and religious diversity, and their empire was multi-ethnic and multicultural. Local languages, religions, and even self-government were allowed as long as people remained loyal to the empire and paid their taxes.

In regions that were too poor to pay in money or produce, the Ottomans often took a tax in the form of people. For example, young boys were taken as tribute captives from villages in the Balkans. They were converted to Islam, educated, and trained into an elite fighting force called the Janissaries who reported directly to the Emperor. Because they were personally loyal to one man, the Janissaries became politically powerful. Fear that the private army would betray him and name another heir Sultan caused new rulers to assassinate all their brothers as soon as they took the throne. The Janissaries were the Ottomans’ most effective weapon from 1363 to 1826, when the sultan decided to disband them in favor of a modern military. The Janissaries mutinied and marched on the Sultan’s palace, but several thousand were wiped out by modern artillery and the survivors executed.

The Ottoman Empire tried to modernize in other ways as well, but fell behind its European neighbors in the nineteenth century and finally met its end during the First World War. We’ll return to that story in a few chapters.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did Istanbul rapidly become the largest city outside China?

- Why was it dangerous that the Janissaries reported personally to the Sultan?

The Safavid Empire of Persia (1501-1736) was a Shiite Muslim dynasty that controlled the region from the eastern border of the Ottoman Empire, through Iran, and into what is now Afghanistan, Georgia, Armenia, and Pakistan. The Safavid’s greatest ruler, Shah Abbas the Great, moved his capital to Isfahan in central Iran. The ancient Persian city had once been a home for Israelite refugees freed from the Babylonian Captivity by Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BCE. Shah Abbas continued the tradition of settling refugees in Isfahan, welcoming hundreds of thousands of Armenians in the early 1600s from the disputed border region separating the Shiite Safavid Empire from the Sunni Ottoman Empire. After the Armenian genocide in 1915, during World War One, the Armenian quarter of Isfahan became one of the oldest and largest Armenian centers in the world.

The Mughal Empire of India was established in 1526 by a Persian-speaking dynasty that traced its authority back to Genghis Khan’s second son, Chagatai. The empire formed in a region that had been conquered by Tamerlane, a Mongol leader who consolidated the remains of several khanates. Tamerlane wanted to reassemble Genghis’s Mongol Empire, and he also considered himself “the Sword of Islam.” He died in 1405 on his way to a planned invasion of Ming China which his successor immediately called off.

Inspired by Tamerlane’s fusion of cultures and religious movements, a new religion called Sikhism developed in the Punjab in the 15th century by combining elements of the traditional Hinduism of the region with Islam. Sikhs opposed India’s caste system, while becoming legendary warriors on the sub-continent.

The Mughals (from whom we get the term mogul) ruled a wealthy empire that included most of the Indian subcontinent and large parts of Afghanistan. It lasted until 1857 and at its peak ruled a population of over 150 million people.

The Mughal golden age began in 1556 with the reign of Akbar the Great, who expanded the empire’s territory but allowed his Indian subjects to keep their languages and religions. Hinduism, which is still the dominant religion of India, is based on ancient traditions and practices originating centuries before the development of Judaism and other religions in the Middle East. It is a polytheistic religion in which the stories of the relations among the gods and goddesses help explain the human condition. Unlike Muslims and Christians, differences related to religious practice have rarely divided Hindus.

Akbar’s grandson Shah Jahan (r. 1628-1658) was also an accomplished military leader, but his reign is remembered for its architectural achievements. Among them is the Taj Mahal, built as a tomb for Jahan’s favorite wife Mumtaz Mahal.

The Russian Empire grew out of resistance to Mongol rule and the fall of Constantinople. A ruler of the Grand Duchy of Moscow named Ivan III (later called Ivan the Great) refused to pay tribute to the Golden Horde and after the death of the last Greek Orthodox Christian emperor, Ivan decided his kingdom would become the new Rome. Ivan (r. 1462-1505) tripled the size of his state and rebuilt the Kremlin in Moscow. His grandson, Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrible, r. 1547-1584) was the first to declare himself Tsar of all the Russias—a title which is Russian for “Caesar.” He annexed the khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia and recruited Cossacks from southern Russia and Ukraine to colonize Siberia.

Russia became the largest kingdom in the world, stretching from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean, but much of it was unoccupied and primitive. Peter I (Peter the Great, r. 1672-1725) visited Europe in disguise for 18 months to study shipbuilding and new administrative techniques that he used to modernize his realm and establish the Russian Empire. We’ll return to Russia later, but let’s explore some of the things that attracted Peter to Europe in the late 1600s.

Questions for Discussion

- Why were the Ottomans and the Safavids always at war?

- What was the advantage for empires like the Mughal of letting subject peoples retain their languages, religions, and customs?

- What attracted Peter the Great to study Europe?

The Enlightenment and Protestant Reformation

Europe’s Dark Ages ended in the 15th century, after the disaster of the Black Death. Even before the bubonic plague arrived, harsh winters and rainy summers beginning around 1310 had caused widespread famine. Feudal lords squeezed their peasants for crops and labor, and states raised taxes. Several million died during the famine, and then two thirds of Europe’s population disappeared between the plague’s arrival in 1347 and 1353. This depopulation threatened the power of the Church and the nobility, as surviving peasants became less patient with the taxes and labor demands of their bishops and lords. Peasant revolts in France and England in the second half of the 14th century showed the feudal system of the Middle Ages was coming to an end.

Unlike the new eastern Muslim empires and the continuing Chinese Empire, Europe was unable to reunify under a single leader and create its own empire—although Austria’s Hapsburg dynasty did its best to lead an alliance optimistically named the Holy Roman Empire for centuries. Too many languages and local centers of power competed for dominance, and the Catholic Church (Europe’s largest landowner) was unable to exercise secular as well as spiritual power. Instead the church found itself pulled into regional contests for power, and in 1309 a French-born Pope moved his residence to Avignon. Seven popes resided in France under the control of the French king until 1378, when another French-born Pope decided to move back to Rome. But the French rulers and a growing class of aristocratic French cardinals were unwilling to give up the power that came with having their own Pope. For another sixty years there were two competing Papal Courts, one in Rome and a rival in Avignon. Although the Avignon Popes have been called Anti-Popes, it’s important to understand that the conflict was primarily about political power rather than about theology or religious doctrine. But theological conflicts were right around the corner.

The arrival of the printing press in Europe in the middle of the fifteenth century allowed critics of the church like the friar Martin Luther to publish books and pamphlets calling for reform. Printing was a Chinese invention that was improved by Johannes Gutenberg, a German goldsmith who understood that moveable type was much more useful for an alphabet-based language than for a character-based system like Chinese. Printing spread classical Greek and Roman texts that had been carried to Europe by refugees from Constantinople, helping ignite the Renaissance (literally “rebirth”) of Europe. A new philosophy called Humanism focused scholars on learning that was not contained in Scripture or in church-approved sources, and on skepticism toward the decrees of religious authorities. Some Renaissance geniuses like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo did not directly challenge the claims of political and religious authorities. Others like Machiavelli and Galileo did. The encounter with the Americas (the topic of the next chapter) also upset a traditional understanding of the world’s origin and history that did not account for the existence of these continents. And religious reformers like Martin Luther used the ability to print books to radically change the way Europeans thought about their Christianity and the Catholic Church.

Questions for Discussion

- Do you think the existence of the Church in Europe was a significant factor in preventing an empire from forming?

- How did the spread of new knowledge encourage humanism and skepticism?

Martin Luther (1483-1546) was an Augustinian monk who began the Protestant Reformation as a reaction against what he perceived as a betrayal of Christian ideals by the wealthy and self-indulgent Catholic Church. The Church had long gone through cycles of corruption and reform, which was usually led by new religious orders of monks (such as the Franciscans and Dominicans in the early 13th century). Among Among Luther’s radical ideas was that the Catholic Church and the Papacy were so corrupt and far away from the teachings of Jesus that Christianity needed to be reestablished, rather than reformed.

Luther received a Doctorate in Theology in 1512 and joined the faculty of the University of Wittenberg in Germany. In 1516 the Catholic Church began selling indulgences to raise money for the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Indulgences were basically tickets for “time off” in purgatory (the place souls went to purify before entering heaven), and Luther objected on theological grounds; he also criticized the wealthy Pope for taxing the poor to build an unnecessary Vatican monument he could easily afford himself. Luther did not intend to split from the Catholic Church, but after his 95 Theses were translated from Latin to German, his criticism of the church and his new approach to theology caught on.

Luther was tried for heresy (no laughing matter: Czech religious reformer Jan Hus had been burned at the stake in 1415) and was excommunicated in 1521. The church banned Luther’s books, but Luther was a prolific writer who went on to publish scores of works using the new printing press condemning the Roman church. Luther translated the Bible into German and wrote a hymnal, so Germans could worship in their own language and understand what they were saying at church—Latin was still the official language of the Catholic Church (and would remain so until 1965).

Printing presses and expanding European literacy helped accelerate the Reformation.

Many members of the nobility, particularly in northern Germany and Scandinavia, embraced Luther’s ideas not only for theological reasons but also for political reasons: they would no longer need to pay tribute and pledge to submit their authority to the Pope in Rome. The Reformation was not the only challenge that alarmed religious authorities into reacting with persecution. When Galileo used a telescope to prove Copernicus’s new theories that extended understanding of planetary motion beyond the second-century theories of Ptolemy, it was not the ancient Greeks who put him under house arrest for the rest of his life and nearly burned him as a heretic, but the Catholic Church—Copernicus and Galileo were rejecting a human-centered world founded by God Himself. Galileo’s challenge to the Church’s outdated description of the natural world was the first of many disputes that science has had (and continues to have) with religious authority.

To be fair, though, the idea that new data should challenge centuries of intellectual and theological tradition was as radical as the idea that the Earth orbits around the Sun and not vice versa. The Church, and European society in general, sought to have eternal and unchanging answers for social and personal conditions. Although today we are accustomed to the idea that new information that can reorganize the ways we understand the world is always becoming available, this was not part of the early modern worldview—which makes Galileo and Luther such radical figures in European and Western history.

As challenges became more frequent, some people tried to resist them by force. The Inquisition and persecution of witches flourished because authorities felt threatened. And the doctrine of papal infallibility did not even exist until the First Vatican Council in 1868 when science had gained a pretty substantial lead over faith…something to think about, since it implies that the Catholic Church never seemed to need to declare infallibility until it was challenged (curiously, the Papacy has only used that authority once, in 1950 in relation to doctrines concerning Mary, the mother of Jesus).

Questions for Discussion

- Was Luther justified in criticizing Church leaders in the Vatican?

- What other motivations did people have for rejecting Roman authority, beyond theological differences?

- Was the Church’s reaction to the challenges of new doctrines and new information about he world appropriate?

The development of science in Europe during the Renaissance would not have been possible without the contributions made by Muslim scholars. During the period when Europe was suffering an intellectual “Dark Age” in the centuries following the fall of Rome, the embrace of Islam in North Africa, the Middle East, and beyond created stability that encouraged the establishment of trade routes to China, which was accompanied by an exchange of ideas and technology. While medieval monks in Europe were busy copying illuminated Latin Bibles and hymnals, scholars like Al-Khwarizmi (780-850) the inventor of algebra, Al-Kindi (801-873) philosopher and musician Al-Zahrawi (936-1013) the father of surgery, Ibn Al-Haytham (965-1040) physicist and father of optics), Al-Biruni (973-1050), historian and scientist, Ibn Sina (980-1037) astronomer and physician, and Ibn Rushd (1126-1198) philosopher and scientist, not only preserved classical Greek philosophy and science that was lost in Europe but made important original contributions to knowledge and culture. Arab mathematicians were also impressed with the Indian number system, which included the concept of zero—in the 1200s, western Europeans began to change from Roman numerals (which did not have a zero) to Arabic numerals. There would be no computers without this revolutionary change in mathematics…try dividing using Roman numerals. Arab scholars helped trigger the Renaissance which led to both the European Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution that produced the modern world we live in today.

In most of their kingdoms and caliphates, Muslim sovereigns respected Jews and Christians as “people of the book.” This was especially important in the Iberian Peninsula—present-day Portugal and Spain—parts of which were dominated by Muslim rulers from 711 to 1492. The introduction of ideas in astronomy, navigation, and mathematics in Iberia soon spread to other parts of Europe. In 1492, Christopher Columbus was able to sail to the New World partly because of Arab naval and navigation technology.

The European philosophers and scientists who led the Enlightenment were dominated by Isaac Newton (1643-1727), who co-invented calculus and produced the first unified theory of nature. Newton’s Principia Mathematica (first published in 1687) created a foundation for all the physics and engineering that followed it, and his theories were basically undisputed until Einstein and quantum physics took up the challenge of describing the universe at the macroscopic and microscopic levels in the early 20th century. Other important Enlightenment thinkers included Émilie du Châtelet, a French aristocrat who studied and translated both Newton and his chief rival, German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Leibniz was the other inventor of Calculus, and the version we now use is actually based a little bit more on his notation system than on Newton’s. These scholars and their colleagues described their field as “natural science” and they tried to find natural laws for society, politics, and the economy to parallel Newton’s discoveries of gravity and optics. John Locke, Adam Smith, and Voltaire formulated ideas about natural rights and society that epitomized what English speakers called Enlightenment and what Germans like philosopher Immanuel Kant called aufklärung (literally, a “clearing up”). Kant famously explained that his aufklärung was humanity’s emergence from its self-imposed adolescence.

One of the consequences of Newton’s physics and other Enlightenment ideas was a crisis in religion. Although Newton himself seems to have believed in a God of some type, the universe he described in his theories did not require a personal deity to be actively engaged in making things happen. Newton’s universe seemed more like one of the new mechanical clocks that were just becoming popular. These complex machines might require a mechanical engineer or a watchmaker to design and build them, but once made and wound they could be left to themselves. Absorbing this watchmaker metaphor, many Enlightenment thinkers rejected the popular religious vision of an activist God who was involved in the day-to-day operation of the world, who rewarded the righteous and punished sinners, or who chose sides in history. The Protestant idea of predestination suggested that there was no free will, and that from God’s perspective time and chance did not really exist—Newton and other European scientists challenged that notion. Many also began to doubt traditional stories of the deity’s interference in history, including the Christian story of Jesus.

For example, Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote an essay on miracles in 1748 that was widely influential and is still a required text for philosophy students. Hume did not argue that miracles could not happen, but that people who believed in miracles were usually not talking about events they had witnessed themselves, but only retelling stories of miracles they had heard or read about (for instance, in the Christian Bible). For Hume, the issue that divided religious believers from skeptics was not actually miracles, but testimony about miracles reported to have happened years, decades, or even centuries ago.

In contrast, Hume argued, laws of nature could be deduced right now because they continued to operate and their effects could be seen every day. Hume left this essay out of the first edition of his book, An Enquiry into Human Understanding, to avoid antagonizing the faithful. But it found its way into print and remains an important challenge to traditions that seek to assert their authority based on supernatural claims.

Questions for Discussion

- How did Muslim scholars contribute to building the modern world?

- Do you think the term Enlightenment (or aufklärung) is an accurate description of the change in our understanding of the world produced by the new “natural science”?

- Were philosophers such as David Hume justified in suggesting that supernatural claims were problematic?

European intellectuals also considered economic questions. Capitalism, the idea that invested wealth can be an engine for economic, social, and technological development, was most famously explained by the English philosopher Adam Smith. An agricultural revolution contributed to increased crop production and population growth in the 1400s, and that led to a surplus population being able to gather in towns and cities to engage in artisanal activities—metropolises which were once mainly centers of commerce and government and Church administration, began to produce goods for trade as well. Even before the development of mechanized textile factories in Great Britain, for example, weavers lived and worked in districts like East London for generations. People began to specialize in particular trades, making products for customers beyond their own families and neighborhoods. Some general-purpose craftsmen like blacksmiths became increasingly specialized, focusing on manufacturing products with broader, mass markets (for example guns or carriage-springs, rather than just horseshoes, nails, hinges, and whatever the locals needed from day to day).

Banks in Europe began forming financial networks that standardized prices across larger regions, such as in Italy, the Low Countries and along the Baltic coast. When transportation and communication are poor, there are many opportunities for arbitrage: buying products cheap where they are abundant and then selling them for a profit where they are scarce. As networks improved, these opportunities decreased – or at least were pushed farther away.

Politics and finance were connected at this time: capitalism did not develop in a vacuum. Although Adam Smith famously described the “Invisible Hand” of market forces in 1776, merchants were heavily involved in government in England and Europe, influencing their nations’ policies and regulations to favor their own goals. Also, as described in later chapters, imperial expansion and colonial armies were indispensable for the spread of capitalism throughout the world.

Question for Discussion

- Is it significant that the stories we tell about the capitalist system focus on the “Invisible Hand” and stress freedom, in spite of the close ties between business and government power?

The Reconquista and Portuguese Trade with Africa

In the next chapter, we will turn to the Americas and their discovery by Europeans. The backstory for this discovery and colonization is the Reconquista, a centuries-long effort by the Portuguese and Spanish to push the Muslim Moors back to Africa. Muslims had taken over most of the Iberian Peninsula beginning in 711. The Reconquista begun by Christian nobles in northern Spain took about 800 years to complete.

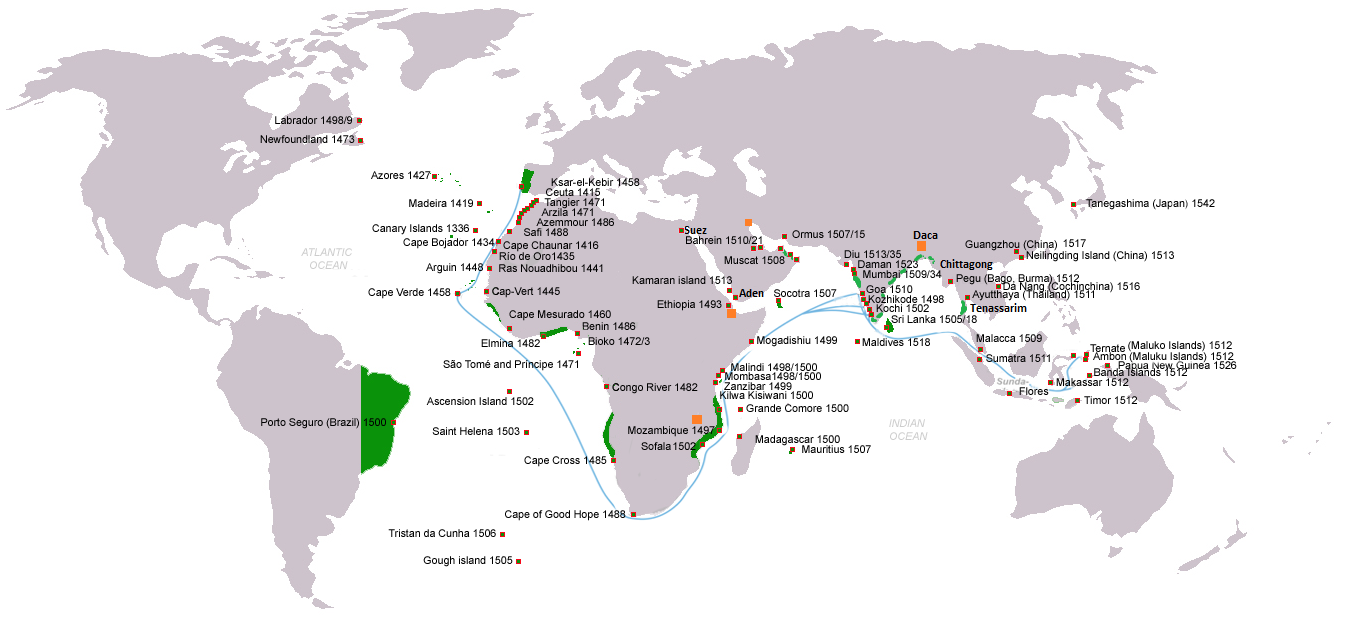

The Portuguese Christians “reconquered” more quickly, because Portugal does not extend as far into the south and the Spanish kings and princes had to contend with the fortified cities of Seville and Granada. However, Portugal also captured Ceuta, a Moroccan fortress in North Africa in 1415, which gave them control over the western Mediterranean and the Atlantic. After a brief but successful war with Castile, the principle kingdom in central Spain, Portugal turned its attention to exploring and acquiring territory along the coast of Africa in the 1430s and 1440s under the direction of Prince Henry the Navigator (Henry’s older brother Edward became King when their father died of the plague). The Portuguese were becoming merchants and traders while the Christian Spanish were still fighting Muslims.

Portuguese mariners, following the route established by Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco de Gama in 1488 and 1497, began sailing to Asia around southern Africa. They conquered coastal east African city-states, established colonies in Angola and Mozambique, and took advantage of a slave-trading network that provided possibly 10 million captives for Muslim slave auctions from the 9th century to the twentieth. Portuguese control of the African coast was one of the reasons the royal court in Lisbon showed little interest in Columbus’s proposal to sail west across the Atlantic to India; it is also why the Spanish were eager to take Columbus up on his plan in search of a route to Asia. We will return to Spain’s interest in Columbus in the next chapter.

As mentioned above, in the wake of the Black Death peasants and artisans demanded and received better pay, leading to increased commercial activity in Europe in the late 1300s which included not only the important Mediterranean trade dominated by Italian merchants, but also in the Baltic and across the English Channel. However, economic expansion was limited by the availability of gold and silver coins, which had been used in exchange since the sixth century BCE in Greece and Persia.

Portuguese merchants were interested in developing a route around Africa to Asia for the trade in spice and silks, but they were pleased to find trade in sub-Saharan Africa as well. The story of the enormous gold reserves of Mansa Musa, Muslim ruler of Mali, were well known to Europeans, especially after he spent enormous amounts of gold in the Middle East during his pilgrimage to Mecca in the 1327. The Portuguese enquired about the availability of gold in every contact that they made in their explorations, and were not disappointed. Present-day Ghana in West Africa was known as the “gold coast” by European traders and imperialists until its independence in 1957, and is still second only to South Africa in gold production on the continent.

African gold certainly aided in economic exchange in Europe, but it was not enough. As we will see in the next chapter, the search for gold was an important motivation for the exploration, conquest, and colonization of the Americas by the Spanish and Portuguese.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did Portugal complete its Reconquista earlier than Spain?

- How did a lack of gold and silver slow economic growth in Europe?

The African Slave Trade

As in most world societies in the 1400s, the institution of slavery was a traditional element in African kingdoms and chiefdoms. Captives were usually acquired through war or as for payment of debts, and enslaved for a period of time or even for life. However, enslaved captives often gained positions in the societies that had captured them, and their children were generally born free. African traders were willing to include this human cargo in commerce with the Portuguese and other Europeans, who readily accepted them as enslaved laborers and domestic servants.

The trade of enslaved people, especially from eastern Europe, had been important in many parts of that continent even into the 1400s. We have seen that in the Ottoman Empire, the Janissaries were eastern European captives who were trained as an elite military corps. The thriving economies of all of the Islamic empires, from Spain through Persia, also created a demand for enslaved people from Europe. The Vikings of northern Europe sold captives from Britain to the Middle East, as did the Frankish kings of western and central Europe, who enslaved prisoners-of-war from among the Slavic peoples of eastern Europe (as had the Romans before them). Although the demand for enslaved labor was less in Europe than in the more economically-developed Muslim world, some European slaves certainly served owners in the fiefdoms of the western Europe.

The human cargo brought to Europe from Africa by the Portuguese in the 1400s, however, became much more highly favored than that of eastern Europe: not only were dark-skinned people more exotic for service in the royal courts, they also could not escape by simply blending in with the local population. One can easily imagine how this would lead to ideas of superior and inferior races—within a few generations, slave-owning “whites” would consider “blacks” to be only suited for enslavement.

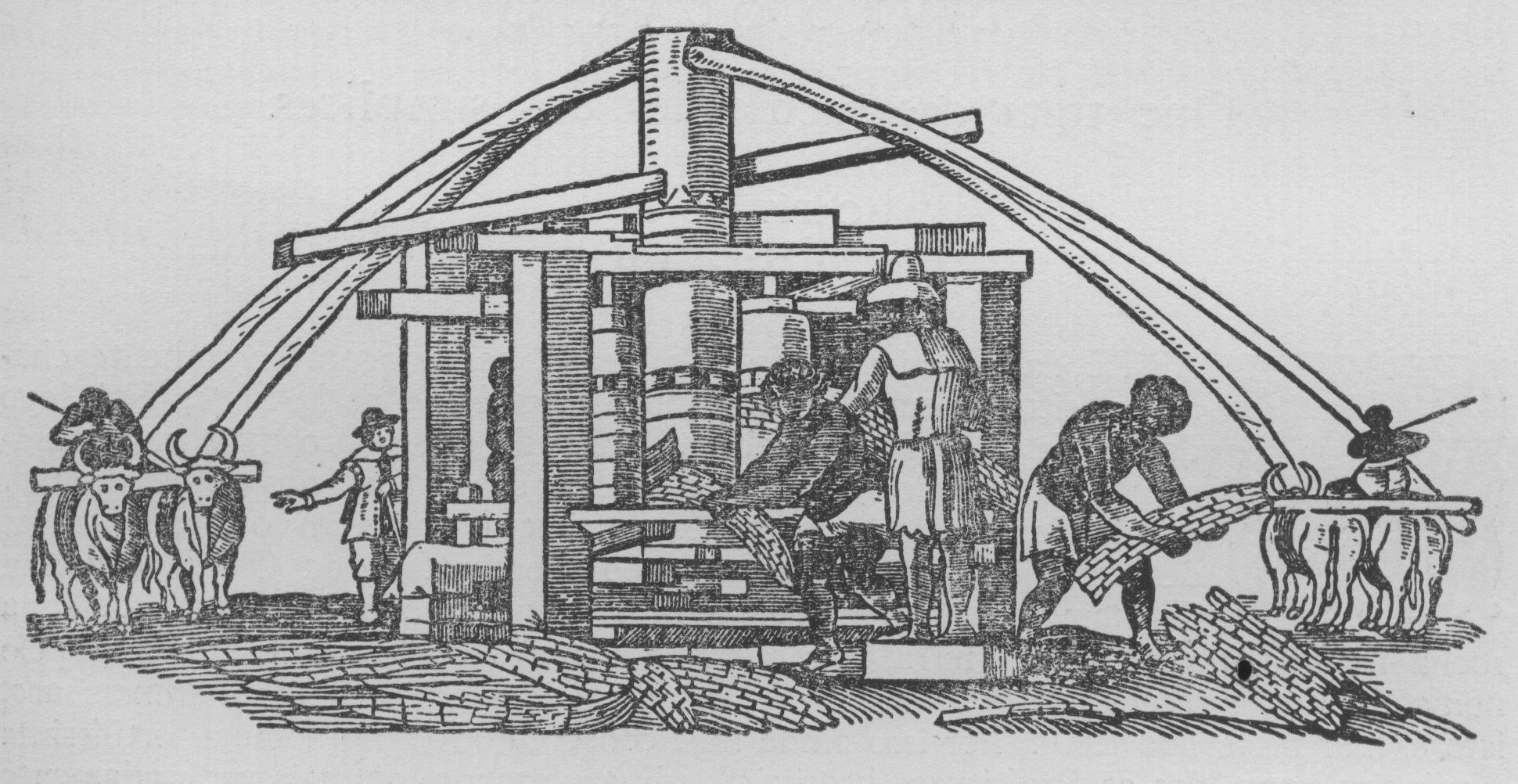

However, what made the African slave trade so lucrative by the 1500s and into the beginning of the 1800s was not the demand for labor in Europe, but rather on sugar plantations on the islands of the Atlantic and later in Brazil and the Caribbean. The vast majority of the enslaved from Africa were used as forced labor in the back-breaking cultivation and processing of sugar cane. Portuguese trade with sub-Saharan Africa coincided with the discovery that sugar cane grew well on the eastern Atlantic islands off the African coast controlled by the Portuguese and Spanish in the 1400s.

Sugar cane itself was first developed in the archipelagos of Southeast Asia. Arab traders brought the plant to the Middle East, where Europeans discovered sugar during the crusades and developed a taste for it through their commerce in the region. Sugar was at first considered an exotic medicinal, but once the Portuguese and Spanish began cultivating cane on the Madeiras and Canary Islands, a European addiction to sugar soon began—replacing honey as the region’s main sweetener.

Eventually, more than two thirds of all enslaved Africans in the Western Hemisphere were involved in cultivating, harvesting, and processing sugar cane in Brazil and the Caribbean. Sugar was such a lucrative cash crop for plantation owners, that they would import enslaved Africans, work them to death in three to five years, and bring in more. We will examine this history in a later chapter.

The Portuguese established the first European colony in sub-Saharan Africa, which they called Angola, in 1575, south of the powerful Kongo kingdom on the West African coast. The Kongolese royal family had converted to Christianity and the ruler, Afonso I, tried to negotiate as a peer with the rulers of Portugal. King Afonso was not able to prevent Portuguese slave traders from indiscriminately taking people with high social status in his kingdom as slaves. Generally only criminals and war captives were sold to foreign slavers, not the sons of noblemen and the king’s relatives. It is unclear whether King Afonso tried to ban all trade in slaves, or whether he compromised to avoid antagonizing his European allies. Either way, his ban was ineffective and the Portuguese carried off more and more slaves to their sugar plantations in Brazil.

Occasionally the Iberians tried to claim that they were doing the Africans a favor by Christianizing them. But conditions on sugar plantations were so harsh that slaves typically only survived a few years. So their conversions were not so much to prepare them for a life as Christians, but to save their souls when they perished from overwork and malnutrition. Over the next several centuries, nearly six times more Africans were forcibly sent to the Americas than Europeans who went willingly. In all, about 16 million Africans were shipped to the Americas in chains. About 4 million died on the way and were thrown overboard into the Atlantic.

Questions for Discussion

- How was the slave trade practiced by the Portuguese different than earlier types of unfree labor?

- How significant was the European interest in sugar to the growth of slavery in the Atlantic world?

Primary Source Supplement #1: King Afonso I of the Kongo’s letters to João, King of Portugal

Sir, Your Highness should know how our kingdom is being lost in so many ways that it is convenient to provide for the necessary remedy, since this is caused by the excessive freedom given by your agents and officials to the men and merchants who are allowed to come to this kingdom to set up shops with goods and many things which have been prohibited by us, and which they spread throughout our kingdoms and domains in such an abundance that many of our vassals, whom we had in obedience, do not comply because they have the things in greater abundance than we ourselves; and it was with these things that we had them content and subjected under our vassalage and jurisdiction, so it is doing a great harm not only to the service of God, but the security and peace of our kingdoms and state as well.

And we cannot reckon how great the damage is, since the mentioned merchants are taking every day our natives, sons of the land and the sons of our noblemen and vassals and our relatives, because the thieves and men of bad conscience grab them wishing to have the things and wares of this kingdom which they are ambitious of; they grab them and get them to be sold; and so great, Sir, is the corruption and licentiousness that our country is being completely depopulated, and Your Highness should not agree with this nor accept it as in your service. And to avoid it we need from those your kingdoms no more than some priests and a few people to reach in schools, and no other goods except wine and flour for the holy sacrament. That is why we beg of Your Highness to help and assist us in this matter, commanding your factors that they should not send here either merchants or wares, because it is our will that in these kingdoms there should not be any trade of slaves nor outlet for them. Concerning what is referred above, again we beg of Your Highness to agree with it, since otherwise we cannot remedy such an obvious damage. Pray Our Lord in His mercy to have Your Highness under His guard and let you do forever the things of His service. I kiss your hands many times.

(dated July 6, 1526)

Moreover, Sir, in our kingdoms there is another great inconvenience which is of little service to God, and this is that many of our people, keenly desirous as they are of the wares and things of your kingdoms, which are brought here by your people, and in order to satisfy their voracious appetite, seize many of our people, freed and exempt men, and very often it happens that they kidnap even noblemen and the sons of noblemen, and our relatives, and take them to be sold to the white men who are in our kingdoms; and for this purpose they have concealed them; and others are brought during the night so that they might not be recognized.

And as soon as they are taken by the white men they are immediately ironed and branded with fire, and when they are carried to be embarked, if they are caught by our guards’ men the whites allege that they have bought them but they cannot say from whom, so that it is our duty to do justice and to restore to the freemen their freedom, but it cannot be done if your subjects feel offended, as they claim to be.

And to avoid such a great evil we passed a law so that any white man living in our kingdoms and wanting to purchase goods in any way should first inform three of our noblemen and officials of our court whom we rely upon in this matter…who should investigate if the mentioned goods are captives or free men, and if cleared by them there will be no further doubt nor embargo for them to be taken and embarked. But if the white men do not comply with it they will lose the aforementioned goods. And if we do them this favor and concession it is for the part Your Highness has in it, since we know that it is in your service too that these goods are taken from our kingdom, otherwise we should not consent to this. . . .

Sir, Your Highness has been kind enough to write to us saying that we should ask in our letters for anything we need, and that we shall be provided with everything, and as the peace and the health of your kingdom depend on us, and as there are among us old folks and people who have lived for many days, it happens we have continuously many and different diseases which put us very often in such a weakness that we reach almost the last extreme; and the same happens to Our children, relatives and natives owing to the lack in this country of physicians and surgeons who might know how to cure properly such diseases. And us we have got neither dispensaries nor drugs which might help us in this forlornness, many of those who had been already confirmed and instructed in the holy faith of Our Lord Jesus Christ perish and die; and the rest of the people in their majority cure themselves with herbs and breads and other ancient methods, so that they put all their faith in the mentioned herbs and ceremonies if they live, and believe that they are saved if they die; and this is not much in the service of God. And to avoid such a great error and inconvenience, since it is from God in the first place and then from your kingdoms and from Your Highness that all the good and drugs and medicines have come to save us, we beg of you to be agreeable and kind enough to send us two physicians and two apothecaries and one surgeon, so that they may come with all the necessary things to stay in our kingdoms, because we are in extreme need of them. We shall do them all good and shall benefit them by all means, since they are sent by Your Highness, whom we thank for your work in their coming. We beg of Your Highness as a great favor to do this for us, because besides being good in itself it is in the service of God as we have said above.

(dated October 18, 1526)

Primary Source Supplement #2: Excerpts from Luther’s Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, 1520.

The Romanists have, with great adroitness, drawn three walls round themselves, with which they have hitherto protected themselves, so that no one could reform them, whereby all Christendom has suffered terribly.

First, if pressed by the temporal power, they have affirmed and maintained that the temporal power has no jurisdiction over them, but, on the contrary, that the spiritual power is above the temporal.

Secondly, if it were proposed to admonish them with the Scriptures, they objected that no one may interpret the Scriptures but the Pope.

Thirdly, if they are threatened with a council, they invented the notion that no one may call a council but the Pope.

Thus they have privily stolen from us our three sticks, so that they may not be beaten. And they have dug themselves in securely behind their three walls, so that they can carry on all the knavish tricks which we now observe. . .

Now may God help us, and give us one of those trumpets that overthrew the walls of Jericho, so that we may blow down these walls of straw and paper, and that we may have a chance to use Christian rods for the chastisement of sin, and expose the craft and deceit of the devil; thus we may amend ourselves by punishment and again obtain God’s favor.

Let us, in the first place, attack the first wall.

There has been a fiction by which the Pope, bishops, priests, and monks are called the ‘spiritual estate’; princes, lords, artisans, and peasants are the ‘temporal estate.’ This is an artful lie and hypocritical invention, but let no one be made afraid by it, and that for this reason: that all Christians are truly of the spiritual estate, and there is no difference among them, save of office. As St Paul says (I Cor. xii), we are all one body, though each member does its own work so as to serve the others. This is because we have one baptism, one Gospel, one faith, and are all Christians alike; for baptism, Gospel, and faith, these alone make spiritual and Christian people.

As for the unction by a pope or a bishop, tonsure, ordination, consecration, and clothes differing from those of laymen–all this may make a hypocrite or an anointed puppet, but never a Christian or a spiritual man. Thus we are all consecrated as priests by baptism, as St Peter says: ‘Ye are a royal priesthood, a holy nation’ (I Pet. ii. 9); and in the Book of Revelation: ‘and hast made us unto our God (by Thy blood) kings and priests’ (Rev. v. 10). For, if we had not a higher consecration in us than pope or bishop can give, no priest could ever be made by the consecration of pope or bishop, nor could he say the mass or preach or absolve. Therefore the bishop’s consecration is just as if in the name of the whole congregation he took one person out of the community, each member of which has equal power, and commanded him to exercise this power for the rest; just as if ten brothers, co-heirs as king’s sons, were to choose one from among them to rule over their inheritance, they would all of them still remain kings and have equal power, although one is appointed to govern.

And to put the matter more plainly, if a little company of pious Christian laymen were taken prisoners and carried away to a desert, and had not among them a priest consecrated by a bishop, and were there to agree to elect one of them … and were to order him to baptize, to celebrate the mass, to absolve and to preach, this man would as truly be a priest, as if all the bishops and all the popes had consecrated him. That is why, in cases of necessity, every man can baptize and absolve, which would not be possible if we were not all priests. This great grace and virtue of baptism and of the Christian estate they have annulled and made us forget by their ecclesiastical law . . .

Since then the ‘temporal power’ is as much baptized as we, and has the same faith and Gospel, we must allow it to be a priest and bishop, and account its office an office that is proper and useful to the Christian community. For whatever has undergone baptism may boast that it has been consecrated priest, bishop, and pope, although it does not beseem every one to exercise these offices. For, since we are all priests alike, no man may put himself forward, or take upon himself without our consent and election, to do that which we have all alike power to do. For if a thing is common to all, no man may take it to himself without the wish and command of the community. And if it should happen that a man were appointed to one of these offices and deposed for abuses, he would be just what he was before. Therefore a priest should be nothing in Christendom but a functionary; as long as he holds his office, he has precedence; if he is deprived of it, he is a peasant or a citizen like the rest. Therefore a priest is verily no longer a priest after deposition. But now they have invented characteres indelibiles, and pretend that a priest after deprivation still differs from a mere layman. They even imagine that a priest can never be anything but a priest–that is, he can never become a layman. All this is nothing but mere talk and a figment of human invention.

It follows, then, that between laymen and priests, princes and bishops, or, as they call it, between ‘spiritual’ and ‘temporal’ persons, the only real difference is one of office and function, and not of estate . . .

But what kind of Christian doctrine is this, that the ‘temporal power’ is not above the ‘spiritual,’ and therefore cannot punish it! As if the hand should not help the eye, however much the eye be suffering . . . Nay, the nobler the member the more bound the others are to help it . . .

Therefore I say, forasmuch as the temporal power has been ordained by God for the punishment of the bad and the protection of the good, we must let it do its duty throughout the whole Christian body, without respect of persons, whether it strike popes, bishops, priests, monks, nuns, or whoever it may be . . .

Whatever the ecclesiastical law has said in opposition to this is merely the invention of Romanist arrogance . . .

Now, I imagine the first paper wall is overthrown, inasmuch as the ‘temporal’ power has become a member of the Christian body; although its work relates to the body, yet does it belong to the ‘spiritual estate’ . . .

It must indeed have been the archfiend himself who said, as we read in the canon law, ‘Were the pope so perniciously wicked as to be dragging hosts of souls to the devil, yet he could not be deposed. This is the accursed, devilish foundation on which they build at Rome, and think the whole world may go to the devil rather than that they should be opposed in their knavery. If a man were to escape punishment simply because he was above his fellows, then no Christian might punish another, since Christ has commanded that each of us esteem himself the lowest and humblest of all (Matt. xviii. 4; Luke ix. 48).

The second wall is even more tottering and weak: namely their claim to be considered masters of the Scriptures . . . If the article of our faith is right, ‘I believe in the holy Christian Church,’ the Pope cannot alone be right; else we must say, ‘I believe in the Pope of Rome,’ and reduce the Christian Church to one man, which is a devilish and damnable heresy. Besides that, we are all priests, as I have said, and have all one faith, one Gospel, one Sacrament; how then should we not have the power of discerning and judging what is right or wrong in matters of faith? . . .

The third wall falls of itself, as soon as the first two have fallen; for if the Pope acts contrary to the Scriptures, we are bound to stand by the Scriptures to punish and to constrain him, according to Christ’s commandment . . . ‘tell it unto the Church’ (Matt. xviii, 15-17) . . . If then I am to accuse him before the Church, I must collect the Church together . . . Therefore when need requires, and the Pope is a cause of offense to Christendom, in these cases whoever can best do so, as a faithful member of the whole body, must do what he can to procure a true free council. This no one can do so well as the temporal authorities, especially since they are fellow-Christians, fellow- priests . . .

. . . Poor Germans that we are–we have been deceived! We were born to be masters, and we have been compelled to bow the head beneath the yoke of our tyrants, and to become slaves. Name, title, outward signs of royalty, we possess all these; force, power, right, liberty, all these have gone over to the popes, who have robbed us of them. They get the kernel, we get the husk . . . It is time the glorious Teutonic people should cease to be the puppet of the Roman pontiff. Because the pope crowns the emperor, it does not follow that the pope is superior to the emperor. Samuel, who crowned Saul and David, was not above these kings, nor Nathan above Solomon, whom he consecrated . . . Let the emperor then be a veritable emperor and no longer allow himself to be stripped of his sword or of his scepter!