10 Decolonization

The defeat of Germany and Japan freed the people of the nations these two would-be empires had conquered, but it also caused people dominated by older empires to question the legitimacy of imperialism. In many of Europe’s and the United States’ imperial possessions, the struggle for independence had begun long before World War Two, however. As you’ll recall from previous chapters, European and American justifications for empire included the claim that people such as Britain’s subjects in India and the America’s in the Philippines were unprepared to stand on their own as independent nations. This claim was undermined by the effectiveness of the Indians and Filipinos in World War II. Filipinos had proven their value as guerrilla fighters. The Japanese only managed to control twelve of the forty-eight provinces of the Philippines, and U.S. General Douglas MacArthur said, “Give me ten thousand Filipinos and I shall conquer the world!” And in imperial possessions like India, the “civilizing project” of empire for generations had including educating local administrators and training military and police forces. The leaders of national liberation often came out of these experiences reasoning that since they were already experienced at running their own nations as administrators for the empires, it was time for the imperialists to leave. Furthermore, the war was full of inspirational examples of Europeans and Asians who fought side by side against the fascist occupiers in their conquered nations. The process was accelerated by the strain of war on the European imperialists. France and the Netherlands had been conquered and themselves occupied as imperial subjects by the Germans, while the British were greatly weakened.

After the war, the nations that had been targeted by Germany (Britain, France, and the Netherlands) all attempted to separate their reaction to this attack from the response of colonial populations to their return. For instance, British leaders like Winston Churchill hoped and expected to expand their empire, which they now renamed a commonwealth, and the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP) had no intention of giving back Iran’s oil fields. This may seem a strange attitude for a nation that was having trouble feeding and housing its own population and leaned on U.S. aid like a crutch. But the British retained their sense of cultural superiority and convinced themselves that their help was still needed to “assist primitive peoples in their march to modernity.”

The timing of national liberation was complicated by the growing conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, which was both a competition to dominate territory and control alliances as well as an ideological struggle between capitalism and communism. This conflict was known as the “Cold War,” since the two countries never directly attacked one another. Instead they fought a series of proxy wars that occurred within the context of decolonization. Each superpower competed to recruit more new nations to their side, pouring military and economic aid into the new developing countries.

Despite the Cold War, at times the process of independence was peacefully achieved through mutual agreement. In the Philippines, for example, the U.S. government handed over power to a local Filipino government within a year of ending the war with Japan. The Americans fully appreciated the sacrifices made by the Filipinos under Japanese occupation and the contributions they had made to their own liberation. President Harry Truman recognized the independence of the Philippines on July 4, 1946. In the days leading up to the announcement, the American and Filipino governments worked out arrangements allowing the U.S. to retain dozens of military bases and for American businesses to have preferential access to the raw materials and markets of the newly independent nation.

Sometimes, peaceful political pressure from organized movements also led to liberation. Indian independence, examined below, is the first and prime example of how non-violent protest, boycotts, and moral suasion could result in freedom. However, there are also many cases in which independence could only be achieved through a more violent guerrilla struggle, as European imperialists were unwilling to let go of their colonies despite the desires of the colonized.

Questions for Discussion

- Why did leaders like Churchill believe they would be able to return to controlling their empires?

- Why did colonized people disagree?

Independence and Partition in British India

One of the earliest examples of decolonization in the post-war era and one that affected an extremely large portion of the world’s population was the British withdrawal from India. As mentioned earlier, India’s long struggle for independence had been led by the India National Congress Party since the nineteenth century.

After 700,000 Indians fought for Britain in the Great war, over 2.5 million soldiers from India fought alongside the British in World War II. More than 87,000 of them were killed in action. The British Field Marshall in charge of the Indian Army from 1942 onward said Britain “couldn’t have come through both wars [World War I and World War II] if they hadn’t had the Indian Army.” When Britain called Indians to arms a second time, the Muslim League supported the British recruitment. However, the Indian National Congress demanded independence before it would agree to help Britain again. When the Congress began a “Quit India” campaign in August 1942, the British imprisoned tens of thousands of leaders for the war’s duration until June 1945. Mohandas Gandhi was among those jailed; he was released in May 1944 due to health concerns.

British war strategy led to a major famine in Bengal in 1943 (modern-day Bangladesh, at the mouth of the Ganges River), and about 3 million people died of starvation. The Japanese invasion of Burma caused about a half million Indian Hindu refugees to flee to neighboring Bengal. At the same time, the British decided to adopt a “scorched-earth” policy in southern Bengal, burning thousands of boats and destroying rice crops so they would not fall into the hands of the Japanese, who they assumed would soon extend their invasion. Poor harvests and wartime inflation in late 1942-early 1943 sent internal rural refugees into Calcutta, the Bengali capital, exacerbating the crisis. The British War Cabinet stalled in sending needed grain to the starving Bengalis—perhaps as policy, perhaps because of the strain on wartime shipping. Very little sympathy was shown for the plight of the Bengalese by the leaders of Great Britain. When presented with evidence of the massive famine, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was incredulous, reportedly asking, “Why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?”

Churchill was not only aware of Gandhi, he was aware of the importance to India to the British war effort. In addition to 2.5 million soldiers, the British government borrowed billions of pounds from India to finance the war. And India was no longer merely a site of famines, it was becoming a source of essential supplies. By the end of the war, India had become the world’s fourth largest industrial power and its increased economic and military influence paved the way for independence from the British Empire in 1947.

However, Indian independence was complicated by internal divisions, some exacerbated by the British themselves during many decades of imperial rule. In particular, the British had encouraged division between the majority Hindu and minority Muslim populations; sending Hindu troops to police the Muslims, and vice versa. Gandhi sought to eliminate the Hindu caste system which deprived the poorest Indians of hope. Castes were an integral part of Hinduism, but under British rule the system had been expanded and the number of divisions had been increased because the foreign rulers found it useful in their divide-and-conquer strategy.

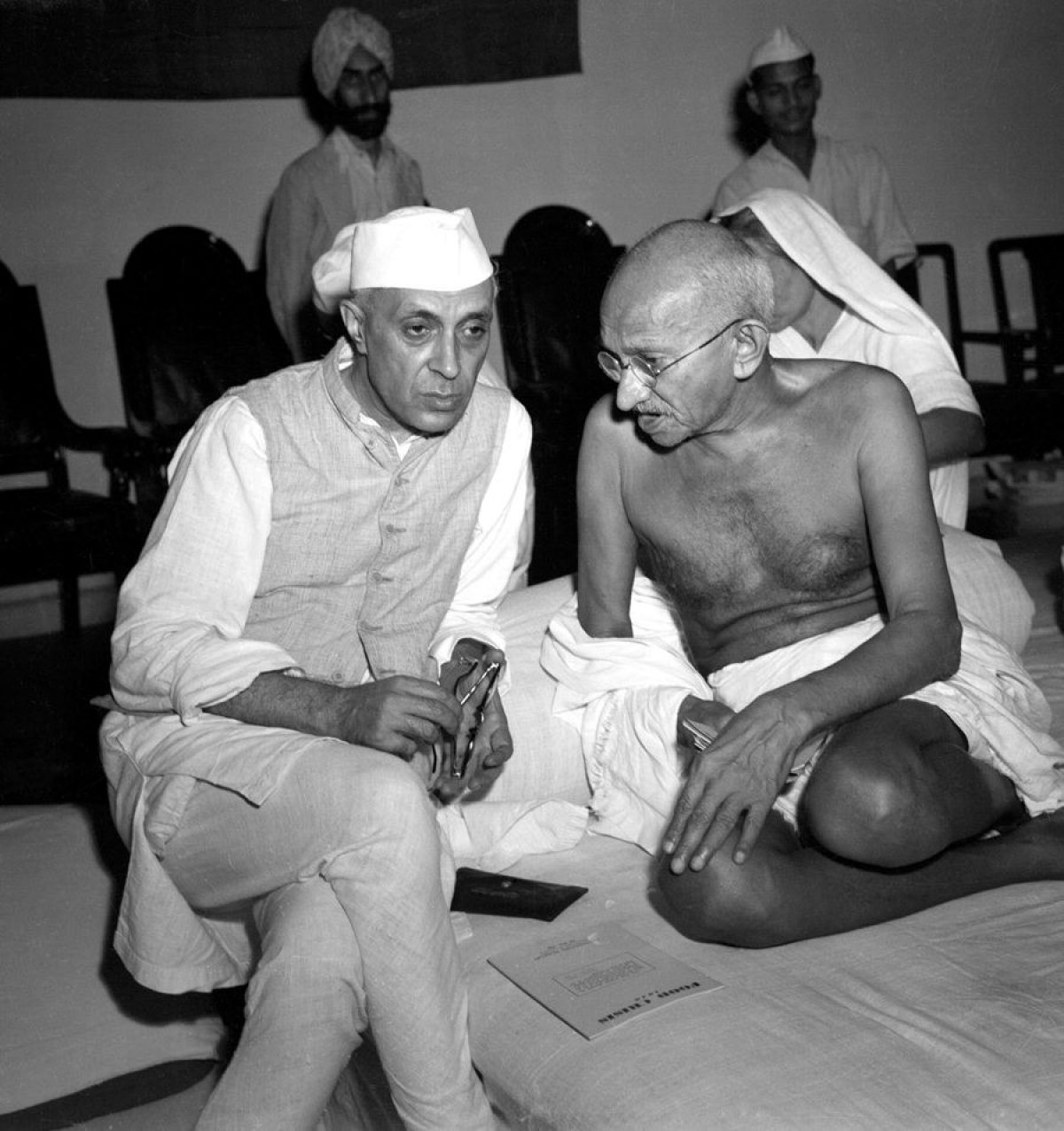

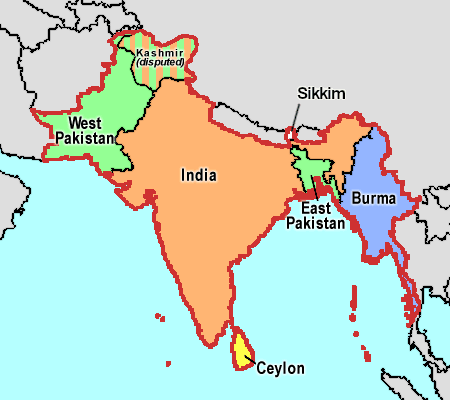

Religious divisions seeped into the independence movement as well. While Gandhi simply wished for an independent, united India after the end of British rule, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League lobbied for the establishment of two states in the territory. Jinnah proposed the creation of a Hindu India and an Islamic “Pure Land” called Pakistan. Jinnah’s position was embraced by Hindu nationalists who wanted to be rid of the Muslim minority. As independence was being negotiated after the war, escalating religious violence suggested that British withdrawal might result in a bloody civil war. Muslims and Hindus attacked each other in different towns and cities, so Congress Party leader Jawaharlal Nehru (who would become the first Prime Minister of India) accepted the partition of India from Pakistan. The new Muslim nation at the time included both the present territory of Pakistan in the west and the eastern region now called Bangladesh.

After independence in August 1947, the partition created a central Hindu nation with two borders into Muslim Pakistan to the east and west. These new, arbitrarily-drawn borders resulted in the displacement of 12 million people, as the former British subjects fled their homes to join the new nations that matched their religions. Millions died during the chaos of the migration and the refugee crises that followed. But even partition was not enough for some Hindu nationalists. Gandhi himself was assassinated by one such extremist shortly after he achieved his dream of independence, in January 1948.

Not only was partition an imperfect solution to religious differences the British empire had exacerbated, but the arbitrary borders were drawn hastily. The state of Kashmir in northern India is still disputed territory. In 1947, a local Hindu prince convinced the British that the majority-Muslim region should stay with India. The Government of Pakistan and many local Kashmiris continue to protest this, causing internal and external conflicts. Since both India and Pakistan are now nuclear nations, the ongoing Kashmir dispute is a legacy of imperialism that may still endanger regional or even global peace.

Question for Discussion

- In what ways were the British responsible for the antagonism between India and Pakistan since independence?

Israel

India was not the only region of the world from which Britain walked away soon after World War Two. Another was Palestine. After World War I, Britain had been given a “mandate” to administer Palestine along with the oil-rich regions of Arabia and Iraq. Between the wars the British continued to allow Zionists, advocates of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, to purchase land and move into the region. Migration of Zionist Jews to the region had begun in the late nineteenth century. This “second wave” of Zionist settlers included dedicated socialists who created cooperative farms called kibbutzim, and urban Europeans who built cities like Tel Aviv—one of the prime examples of the Bauhaus architectural style popular in Germany in the 1920s. However, accelerating Zionist immigration increased tensions with the Palestinian Arabs who had lived in the region for centuries. Competition for land and water, as well as for political dominance, resulted in violent riots between Arabs and Zionists in 1921, and a longer Arab revolt in Palestine from 1936 to 1939.

As mentioned previously, the Nazi Holocaust seemed to prove the Zionist thesis: that Jews would never be safe in Europe and needed to establish their own homeland. The British considered a petition to allow 100,000 refugee survivors of the Nazi camps to resettle in Palestine, but hesitated due to opposition from Palestinian Arabs and the nearby Arab states. Zionist settlers had already formed a mutual defense force, the Haganah, in the 1920s. After the war, the Haganah turned to sabotage against the British occupation and organizing illicit arms shipments.

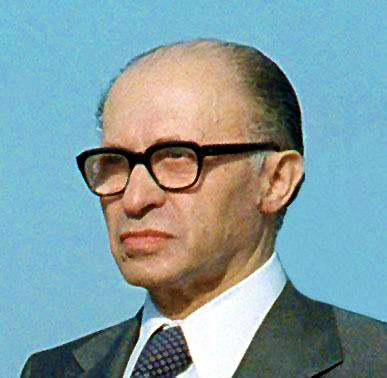

More radical terrorist organizations also formed, including the Irgun, which in 1946 bombed the British headquarters at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 people. The Irgun also led a terror attack on the Palestinian town of Deir Hassin in 1948, in which over a hundred perished, including women and children. Despite apologies from more mainstream Zionist groups (and, later, the Israeli government), the Deir Hassin massacre has served as a rallying cry and a justification for terror attacks against Israelis by different Palestinian-related terrorist groups ever since.

In 1947, the British relinquished their “mandate” over Palestine to the new United Nations, which tried to develop a new map for a Jewish homeland—the new state of Israel—while taking into account the presence of the Arab Palestinians. The Zionists received more land than could be justified by their numbers at the time, as well as some of the more valuable agricultural and water resources. As the British withdrew in May 1948, Israel declared its independence based on the U.N. borders, which the both the local Arabs and the neighboring Arab countries had rejected. Israel’s new neighbors immediately declared war, but the new nation had powerful allies and was willing to fight for its survival. Israel defended itself and actually extended its borders. The Israelis claimed they needed to have a wider defensive perimeter and that the Arab Palestinians had abandoned many of their towns anyway; which many had because they thought the Arabs would win a decisive victory. Israel eventually destroyed over 500 Arab villages and cleared out Arab neighborhoods in major cities, causing the over 800,000 “temporary” Muslim and Christian war refugees to seek more permanent shelter in neighboring Arab nations. A series of wars in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982 continued the conflict.

With tenacity, superior organization, and a lot of aid from the United States and Europe, the Israelis held their own in these conflicts and embraced an ongoing expansion of the Israeli area of settlement in a policy of creating “facts on the ground.” The Arab world, considering Israel an arbitrary creation of western powers, refused to recognize Israel as a legitimate state. Peace processes with individual Arab nations have brought agreements and diplomatic recognition from Egypt in 1979, to whom Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula, taken in the 1967 war; and Jordan in 1994, which relinquished its claim to the Palestinian West Bank of the Jordan River.

Weariness with war and terror, and a desire to qualify for U.S. military and economic aid, have led the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Sudan to recognize Israel in 2020. But it is one thing to have recognition from a government, and another thing to be accepted as a nation by the “Arab Street”. Ordinary Arab people are often tired of authoritarian rule in their own countries, and are more supportive of the Palestinian Arab cause than the governments ruling them.

Questions for Discussion

- Is it surprising that Palestinians resent Israel’s existence?

- Do you think the major issue is anti-Semitism, when both Muslim and Christian Arabs have fought Israel?

- How might the extremely high level of financial and military Israel receives from the U.S. complicate Middle-eastern diplomacy for both the Israelis and the Americans?

“British” Kenya

Although Great Britain had retreated relatively peacefully from India and had given up its control over Palestine voluntarily, this was not the universal pattern. Reluctance to abandon colonies was especially a problem in Africa, where there were British settlers rather than administrators. By the early twentieth century, 30,000 British settlers occupied all the best farmland in Kenya, which they had bought or had been assigned by the colonial government, leaving 5 million Kenyans without. The settlers were people something like the Dane Isek Dinesen, who wrote of her experiences in Kenya in her 1937 book Out of Africa, although most were generally less respectful and interested in the natives than she. More were like farmer Mike Blundell, a white man featured in a Life Magazine article who had arrived as an unskilled farm apprentice but because he was white had managed to get hold of 1200 acres of “virgin bush.” Blundell despised the local Kikuyu tribes and believed the “Kukes” as he called them had only “come out of the trees” in the last 50 years, and probably as a result of contact with the whites. The attitude of British farmers in Kenya was much like the relationship two centuries earlier between English colonists in North America and the Native Americans.

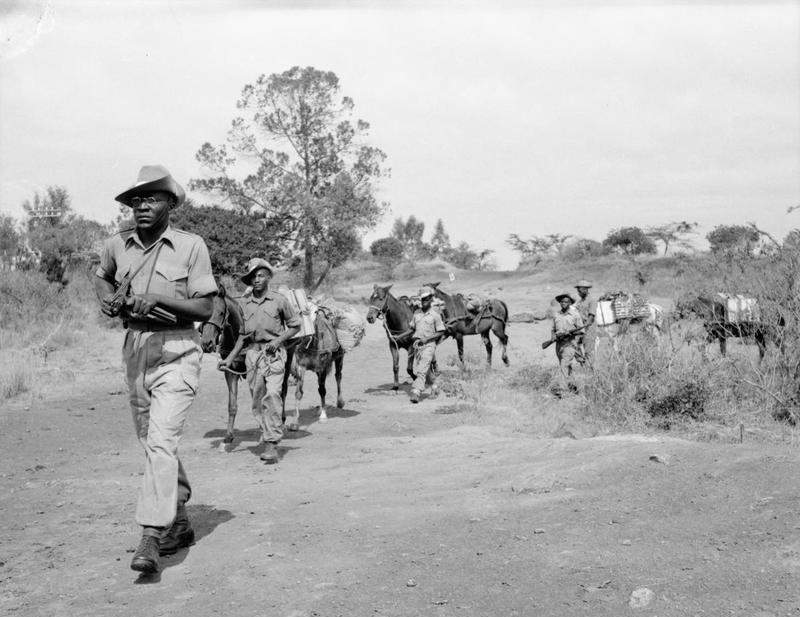

But this was the twentieth, not the eighteenth century. In Kenya, a resistance movement called Mau Mau began in 1952 when natives restricted to reservations in their own country revolted. After World War II, 1.25 million Kikuyu had 2,000 square miles of marginal farmland to feed themselves while 30,000 British settlers had 12,000 square miles in the fertile hills of the Central and Rift Valleys, where they grew cash crops like coffee using native labor. The Mau Mau uprising protested this injustice and the British colonial government responded. Declaring a state of emergency, the British moved about 450,000 Kikuyu to concentration camps and another million were restricted to “enclosed villages”. Prisoners suspected of being Mau Mau fighters were often tortured by British troops (typically they were flogged to death, burned alive, or castrated). In June 1957 the British attorney general of the colony wrote to the governor that the mistreatment of captives was “distressingly reminiscent of conditions in Nazi Germany or Communist Russia.” He reminded the governor, “if we are going to sin, we must sin quietly.”

The uprising lasted until 1963, partly because white settlers could not easily abandon their property and go back to Britain. Power in Kenya eventually shifted from the British colonial government to a native government, initially made up of many members of the Kenyan African National Union (KANU) that had led the resistance. Its leader, Jomo Kenyatta, became Kenya’s first indigenous Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964 and was President of Kenya and led the KANU party until his death in 1978. Kenyatta, like other leaders such as Gandhi and Ho Chi Minh, had travelled internationally. He attended the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow as well as University College in London and the London School of Economics, although when the press mentioned him, they typically observed he had “studied in Russia”. Kenyatta was imprisoned from 1954 to 1961 for allegedly leading the rebellion, and became leader of the party and the nation when released. Kenyatta initially tried to heal the nation by downplaying the atrocity of the recent war, and he welcomed the multinational corporations that dominated the Kenyan economy. The government helped African farmers buy out white landowners and expanded education and social support programs. Kenyatta was often accused of being a socialist, but he was also hated by the British settlers for being married to a white woman. His economic policies balanced capitalism and social welfare. Kenyatta was regarded by many Africans as a strong Pan-Africanist and was hailed as the Hero of the Kikuyu. The current (2020) president of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, is his son.

Question for Discussion

- Why might it be significant that revolutionaries like Kenyatta, Ho, and Gandhi were world travelers?

“French” Algeria

The British were not the only Europeans to lose their colonial empires. Although France had been conquered and occupied by Germany, after the war the French fully expected to regain their colonial possessions in Africa and Asia and resume where they had left off. Their subject peoples in the colonies had different ideas. In Algeria, revolutionaries had been organizing to resist French imperialism since before the war. An Algerian People’s Manifesto was published in 1943. On the morning of May 8, 1945, (the day that Nazi Germany surrendered, or VE Day), a parade of about 5,000 Muslim Algerians celebrating the war’s end was met by armed French police. Marchers and police exchanged gunfire and during the battle people on both sides were shot. A few days later a smaller, peaceful protest by the Algerian People’s Party was violently repressed by police. Rural Algerians responded by attacking ethnic French settlers, called pieds noirs, killing 102 Europeans. The French retaliated, killing between 6,000 and 30,000 Algerians.

The Algerians did not forget this massacre and nearly a decade later, on November 1, 1954, Algerian guerrilla forces attacked civilian and military targets throughout the country. The National Liberation Front (FLN), encouraged by the fact France had just lost their colony of French Indochina, called on Muslims in Algeria to join in the struggle for independence. The FLN applied guerrilla “hit and run” tactics as well as terrorism and torture of both French pieds noirs and Africans suspected of supporting the regime. The French were equally brutal, and by 1956 there were more than 400,000 French troops in Algeria.

The war lasted eight years and killed over a million people. The French military lost 25,000 troops and about 3,000 European civilians were killed. French officials estimated the Algerian death toll at 350,000, but other French and Algerian estimates range from 960,000 to 1.5 million. The United States recognized Algeria’s independence in September 1962 and the country became the 109th member of the U.N. in October.

Question for Discussion

- How might the scope of European retaliation, killing about ten Africans for every European killed, have effected world public opinion?

“French” Indochina

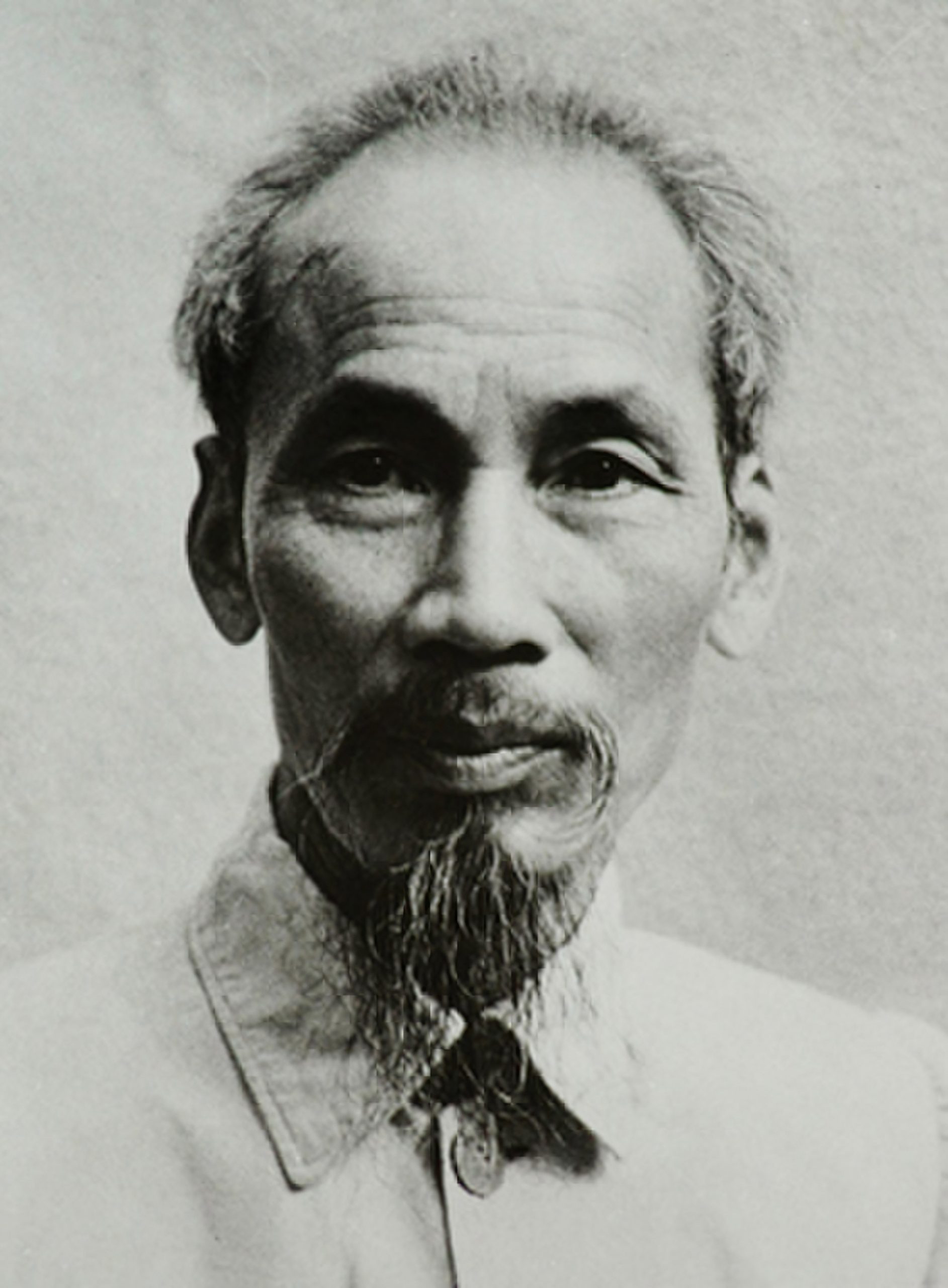

France had also expected to return to power in its colonies in French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), but the people living there also had other ideas. Revolutionaries were led by Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969), who as a young man had worked as a kitchen helper on a steamship from Saigon to Marseille in 1911. Ho actually applied to the French Colonial Administrative School in Marseille, but his application was rejected and he returned to working on ships and traveling the world for another five years (it’s interesting to imagine how history would have been different if he had been accepted). He visited the U.S. several times in his travels and later claimed to have met Black nationalist Marcus Garvey. Ho worked in England and France between 1913 and 1919. He joined a group of Vietnamese nationalists in Paris, and at the end of World War I, the group petitioned at the Versailles peace talks for recognition of the civil rights of Vietnamese people, citing Woodrow Wilson’s statements about self-determination in the famous “14 Points” speech. Ho wrote a letter to Wilson, but the American President ignored him.

Rebuffed, Ho continued living in France in the early 1920s, meeting socialists and becoming a founding member of the French Communist Party. Ho began to write articles that were noticed in Moscow and he was invited to visit the Soviet Union. In 1923, Ho studied at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow before moving to Guangzhou China in 1924. When Chiang Kai-shek cracked down on communists in China, Ho returned to Moscow and then moved on to Thailand. In late 1929 he moved through India to Shanghai and Hong Kong. By this time, he was becoming well-known in revolutionary circles. Ho was arrested in Hong Kong in 1931 but escaped and returned to Russia.

In 1938 Ho returned to China as an advisor to the Chinese Communist army. In 1941 he returned to Vietnam to lead the independence movement there. The Japanese invasion created an opportunity for the patriots, who were aided in their resistance of the Japanese and Vichy French by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA. At the end of World War II, Ho wrote a declaration of independence for Vietnam based on the US Declaration from 1776. Ho repeatedly petitioned President Harry S. Truman to recognize Vietnam, citing the Atlantic Charter, but Truman never responded. Meanwhile, British and Chinese troops occupied the country in support of France. Vietnamese rioted and killed a hundred or so French citizens, and in retaliation French troops armed Japanese prisoners of war and massacred over 6,000 Vietnamese. This was the same pattern of asymmetrical force used by empires against their subjects throughout the colonial period. However, the story of Vietnam is only half over; we will return to it in the next chapter when we discuss the Cold War.

Kenya, Algeria, and Vietnam were not the only places where the imperial powers and their international allies responded violently to movements of national liberation among the colonized. For example, the French killed 80,000 in Madagascar in 1947 when the people of that island supported independence. The Indonesian War of Independence raged from the former Dutch East Indies declaration of independence in 1945 and The Netherlands’ recognition of their claims in 1949. About 8,000 Dutch troops and their allies were killed, and about 100,000 Indonesians. And growing fears of international communism pushed the United States government into supporting some of these actions. Although the Americans had peacefully let go of the Philippines, the U.S. military helped Korean militias massacre about 60,000 members of a peasant insurgency. The Korean Peninsula had been divided at the end of World War Two, like Germany, into Soviet and U.S. occupation zones. Unsurprisingly, the two rivals backed communist and non-communist leaders in North and South Korea. The resulting conflict, the Korean War (1950-1953), will be examined in more detail in the next chapter on the Cold War.

Questions for Discussion

- Is it significant that Ho Chi Minh worked with the OSS during World War II when he was opposing Japan?

- How many chances were there in Ho’s story, where history could have turned out differently?

New Nations and Development

The newly-founded countries in Africa and Asia all faced the challenges of establishing borders, forming new governments, building economic self-reliance, controlling natural resources, and working toward a more just and equitable society. In previous chapters, we have seen how the new nations in Latin America had confronted similar issues since the early nineteenth century. Other older but less-industrialized countries, like Iran, also addressed questions of development and national sovereignty.

One of the major challenges faced by these new nations was the problem of borders. The administrative boundaries drawn by the European imperial powers did not always follow any logic that served the colonized peoples. We have seen that disagreements over Kashmir continue to cause tensions between India and its neighbor Pakistan, which are further complicated by the fact that both India and Pakistan are now nuclear powers (India since 1974 and Pakistan since 1999). India also supported the independence of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in the early 1970s, a conflict which brought famine and death to hundreds of thousands in the same region that had been starved out thirty years before during World War II.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s division by the European powers had also haphazardly thrown together peoples who wanted separate nations. Violent conflicts based on tribal loyalties have caused civil wars and political instability. For instance, when the Igbo people tried to form a separate nation in Nigeria in 1965, the three-year civil war that followed killed thousands before Biafra was defeated. The disputed region is petroleum-rich (Nigeria leads Africa in oil production); so that even today, Igbo separatists harass the Nigerian government, resentful that their oil wealth seems to benefit the rest of the country more than it serves them.

Such conflicts do not only result in separatist civil wars. Although no tribe advocates establishing their own independent state in Kenya, conflicting tribal loyalties often spill over into political competition. Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta tended to favor his Kikuyu people, who were a plurality but not a majority in Kenya, during his long presidency. Resentment by the Luo and Kalenjin people led to realignments of political parties, which caused widespread violence after a contested election in 2008, with the death of hundreds.

Nearly all of the new nations embraced democratic constitutions. But it is one thing to write a constitution, and quite another to actually follow it. Like the older republics in Latin America, many new nations suffered through periods of authoritarian rule. Often, the military would step in and overthrow a democratically-elected government in times of perceived or actual economic or political chaos. The colonial powers had trained militaries as well as educating local administrators; army officers often felt that they were in a better position to rule their countries than incompetent and corrupt politicians, even if they had been elected democratically. Similar arguments had been made by fascists and authoritarians in interwar Europe; the mistakes of the imperialists were often repeated in their former colonies. The Cold War complicated this situation, as fear of communist-led “wars of national liberation” frequently caused the United States and other Western “democracies” to support repressive military dictatorships.

Again, the example of India and Pakistan illustrates the problem of political stability in the new nations. India successfully embraced democracy and remains today the largest democracy by population. One reason for this was the popularity of the Congress Party, which dominated Indian politics until the 1990s. Another is the prominence of the Nehru family: after Indian Prime Minster Jawaharlal Nehru died of natural causes in 1964, he was succeeded by his daughter Indira Gandhi (no relation to Mahatma Gandhi) for twenty years, and she was followed by her son Rajiv Gandhi. Their dedication to democratic traditions brought a degree of political stability, although India was not free of problems that beset other new nations. Sikhs advocating for more power in Hindu India murdered Indira Gandhi in 1984 and ethnic Tamil separatists assassinated her son Rajiv in 1991. Despite these shocks, elections continued, and even opposition parties have taken the reins of government peacefully from the Congress Party since the 1990s; including current Prime Minister Narendra Modi, elected in 2014.

On the other hand, Pakistan has been ruled by their military more often than not since independence. Unlike in Nehru’s India, Pakistan did not benefit from an initial long premiership by its founding father, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who died barely a year after independence of tuberculosis and lung cancer. Internal and international crises led to repeated interventions by the Pakistani military into national government. The 2013 Pakistani elections were the first time one democratically elected government peacefully replaced another. But even today the military plays an independent, often secretive role in Pakistan, especially in foreign policy.

All of the new nations were faced with the question of how to develop their economies. Some governments were inspired by the apparent rapid industrial growth in the Soviet Union under Stalin’s Five-Year Plans, while others embraced the role of providing natural resources to the mature industrial economies of the West. Independent economic self-reliance was often difficult to achieve when industries and public utilities remained foreign-owned. Some new governments nationalized these businesses, so that the nation owned and operated them in the name of the people rather than for the profits of foreign shareholders. In India, for example, Nehru’s government nationalized the railroads, electric utilities, and communication systems. Seeing the results of India’s actions, many new African and Asian countries did the same.

Critics of nationalized industries argued that like the collectivized agriculture and industry of the Soviet Union, these businesses faced no competition. Their objections were taken seriously, partly because Stalin’s lies about the success of the Five Year Plans were finally discovered, and partly because nationalized industries often became inefficient as positions in a railroad or a telephone company transformed into political plums: no-show jobs awarded to loyal supporters. The foreign businesses that had been pushed out supported this view, and a reaction to nationalization, privatization, began in the 1980s. In India the push for privatization was led by Rajiv Gandhi, the grandson of the leader who had led nationalization efforts. In privatization, government-run industries were sold back to the private sector, which on occasion included, once again, foreign investors. Newly-privatized industries often initially embraced cost-cutting efficiencies and more competent management, repairing broken-down electrical grids and rail lines. However, as profits were once again exported abroad or held by a tiny local elite, there has been a push back against privatization, as some leaders once again seek more benefits for the entire nation.

Questions for Discussion

- How did Stalin’s lies about the success of the Five Year Plans affect the decisions of newly decolonized nations?

- In what ways did the problems of borders and religious differences continue to plague the new nations?

In recent decades, a leader in the political push for privatization has been the International Monetary Fund (IMF), first established at the July 1944 conference at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire mentioned earlier. Even before the war ended, forty-four allied nations sent 730 delegates to establish what would become a global system for regulating international balances of commercial payments and securing what they hoped would be financial stability for the post-war world. Initially, they were mainly thinking of creating institutions and policies that would both rebuild war-torn Europe and Asia and prevent the hyperinflation and Great Depression that led to so much instability between the wars.

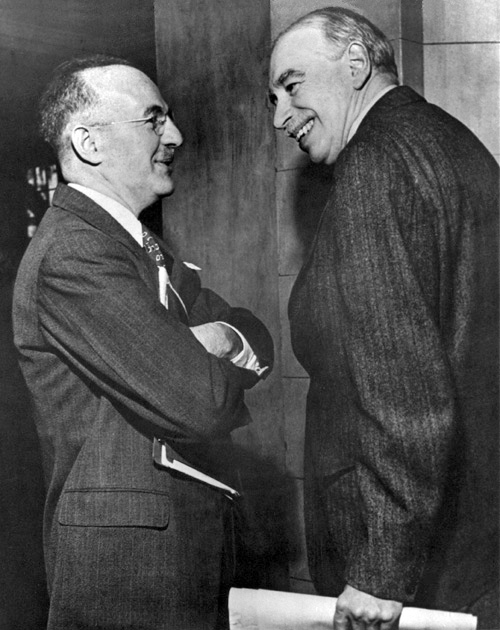

There were two architects of the meeting and the global financial plan that came from it. John Maynard Keynes was the British economist who had pioneered the “demand-side” economic theory that people like U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt had adopted to confront the Great Depression. Keynes’ claim was that by spending money, the federal government could jump-start the economy, create jobs, and put the money in people’s pockets that would enable them to buy consumer products. This plan was temporarily derailed by war production and rationing, so it is unclear to many economists that Keynes was right and that deficit spending and government borrowing was the key to ending the Depression. At the time of the Bretton Woods Conference, Keynes was the chief advisor to the Chancellor of the Exchequer in Britain. The American, Harry Dexter White, worked closely with Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. White dominated the conference and although he considered himself a Keynesian, he vetoed Keynes’s proposal for the International Clearing Union (ICU), a central bank with its own currency, the “bancor”. White opposed the ICU and instead proposed an International Stabilization Fund that would help debtor nations maintain their balance of trade. This grew into the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IRBD), which became the World Bank. The U.S.’s goal was to promote international development but also to help establish markets for American manufactures, now that the war effort had greatly increased U.S. manufacturing capacity.

Another reason the U.S. rejected the ICU and the “bancor” was to protect the leading position of the dollar in the world economy. Since the U.S. had the strongest economy in the world at the end of the World War II, they also dictated the trade provisions agreed to at the conference. The major provisions of the agreement were a foreign exchange system with the U.S. Dollar as its base currency, along with a pledge by members to convert their currency to gold for trade-related demands. Countries were required to adopt the gold standard and were not allowed to alter their currency’s exchange rate by more than 10%. This would prevent debtor nations from escaping their obligations to creditors by simply inflating their currencies. Finally, all members had to pitch in to the new bank’s assets, although the U.S. put up most of the money.

Bretton Woods also drafted a set of trade-related recommendations and an International Trade Organization (ITO) was proposed, with a goal of reducing tariffs. The United States Senate, however, was not interested in ceding its authority over tariffs to a new international organization, and did not ratify the ITO’s charter. The less aggressive General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was adopted in its place. We will discuss it when we cover Globalization.

Bretton Woods created the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which lends money to distressed economies suffering from hyperinflation or other financial chaos and, as a condition for credit, stipulates how a borrower country should reorganize government spending and finance. The IMF was designed to oversee the international monetary and financial systems and to monitor member nations. The U.S. undermined this mission when it went off the gold standard in 1971. Inflationary government spending on both the war in Viet Nam and the War on Poverty begun by Lyndon Johnson, and a worsening balance of trade led the Nixon administration to fear that foreign holders of dollars would demand conversion to gold, which would rapidly wipe out the U.S. gold reserves, held in Federal Bullion Depositories such as Fort Knox. Nixon’s unilateral decision was ratified by Congress in 1978. By the end of the 1970s, no major currency was convertible for gold. Although the dollar is no longer redeemable in gold, the United States continues to maintain a gold reserve of over 8.1 metric tons , more than half of it stored at Fort Knox in Kentucky. The next largest national gold reserve, roughly 3.3 metric tons, belongs to Germany

Bretton Woods created the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which lends money to distressed economies suffering from hyperinflation or other financial chaos and, as a condition for credit, stipulates how a borrower country should reorganize government spending and finance. The IMF was designed to oversee the international monetary and financial systems and to monitor member nations. The U.S. undermined this mission when it went off the gold standard in 1971. Inflationary government spending on both the war in Viet Nam and the War on Poverty begun by Lyndon Johnson, and a worsening balance of trade led the Nixon administration to fear that foreign holders of dollars would demand conversion to gold, which would rapidly wipe out the U.S. gold reserves, held in Federal Bullion Depositories such as Fort Knox. Nixon’s unilateral decision was ratified by Congress in 1978. By the end of the 1970s, no major currency was convertible for gold. Although the dollar is no longer redeemable in gold, the United States continues to maintain a gold reserve of over 8.1 metric tons , more than half of it stored at Fort Knox in Kentucky. The next largest national gold reserve, roughly 3.3 metric tons, belongs to Germany

Losing their original reasons for existence, the IMF and World Bank were forced to adapt. Rather than enforcing convertibility, the IMF began using its ability to loan interest-free development money to debtor nations as a way to intervene in and direct the economic policies of the borrowers. The IMF’s stated aim was to avoid or mitigate financial crises, using the “conditionality” of their loans. The IMF now analyses nations’ economic policies and offers “advice” which must be taken in order to receive IMF loans.

The changes the IMF and the World Bank require are called Structural Adjustment Programs. They typically include deregulation, privatization, and removal of trade barriers. All of these measures have been criticized by debtor nations as being more beneficial for the lenders in developed industrialized nations rather than for borrowers in the developing world. Other structural adjustments can include reducing trade deficits through currency devaluation, austerity programs to decrease budget deficits, eliminating social welfare programs, cutting public services, focusing economic output on resource extraction, and attracting foreign direct investment. This current bundle of structural adjustment programs is known as the Washington Consensus and is associated with neoliberalism or market fundamentalism, which we will discuss in a later chapter. Even in its more modest formulation, IMF policy is designed to liberalize trade, deregulate and privatize industries, and protect property rights above all other concerns.

Questions for Discussion

- What do you think the response of the communist U.S.S.R. may have been to the Bretton Woods Conference and the IMF?

- Is it possible to interpret the IMF’s role as global lender as a continuation of a new, economic form of imperialism?

The Green Revolution

The explosive improvement of agricultural yields throughout the world known as the Green Revolution began in the 1960s in a research station on the edge of the Mexican desert. The scientist most associated with these advances is Norman Borlaug, an agronomist who developed a disease-resistant strain or dwarf wheat that increased yields of the grain worldwide, especially in developing nations facing high population growth and threat of famine. Borlaug (1914-2009) grew up on a 106-acre Iowa farm and attended the University of Minnesota in the 1930s. Borlaug’s education included a stint in the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression. He later remembered that seeing the effect of hunger on people in America “left scars” on him and motivated him to try to solve the problems of supplying food to a growing world population. Borlaug continued at the U of M after graduation, eventually earning a Ph.D. in plant pathology and genetics in 1942. Borlaug then went to work as a microbiologist at DuPont. After a couple of years with DuPont, he joined the Cooperative Wheat Research Production Program, a joint venture of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Mexican Ministry of Agriculture.

Borlaug found that local Mexican farmers resisted planting wheat because a fungus called stem rust reduced their yields so much they couldn’t make a living. A related problem with wheat farming in Mexico was that the plants grew too tall when heavily fertilized and then “lodged” or fell over prior to harvest. Borlaug and his team bred a new strain of dwarf wheat that would not grow too tall when fertilized and that also resisted rust. The process took ten years and over 6,000 cross-breeding experiments between different types of wheat. The new wheat had the additional advantage of being able to be planted twice per year. Although it took Borlaug a while to convince local farmers to try his new hybrid, they could see his fields and were finally convinced. Between 1950 and 2000, Mexican wheat yields increased between 400% and 500%.

In the 1960s, as the program was becoming successful in Mexico, it was exported to India, which was facing famine. American farmers shipped a fifth of their wheat production to India in 1966 and 1967. The Indian situation seemed dire, especially since India’s population crossed the 500-million mark in 1966 and was expected to grow by another 200 million by 1980. The prediction was accurate: India crossed 700 million in the early months of 1981, on its way to a current level of 1.38 billion. India imported 18,000 tons of Borlaug’s seed wheat in 1966. Wheat yields increased from 12.3 million tons in 1965 to 20.1 million tons in 1970. By 1974 India was self-sufficient in all cereal grains and the USAID (US Agency for International Development) began calling Borlaug’s work a Green Revolution. Since the 1960s India’s food production has increased faster than population growth. By 2000 India was producing 76.4 million tons of wheat.

India’s improved crop yields, driven by Borlaug’s improved wheat, have made it a net exported of wheat. India began exporting wheat regularly in the 1970s and since 1980 has exported wheat every year except three. The nation’s exceptional agricultural turnaround was made possible by Borlaug’s new wheat, but also by extensive use of fertilizer, irrigation, and machinery. The improved crop and techniques have prevented up to 100 million acres of virgin land from being converted to farmland. This savings amounts to 13.6% of India’s land, or about the area of California. Borlaug predicted that as world population continued to rise, only new crops and improved farming techniques would save the world’s remaining forests and uncultivated lands.

Although the Green Revolution has undoubtedly saved lives and allowed populations in India to increase dramatically, Borlaug and the Green Revolution have been criticized for bringing capital- and energy-intensive western agricultural techniques to regions of the world that had once relied on subsistence farming. Western-style farming tends to reward large-scale operators and often provides even greater rewards to manufacturers of agrochemicals and machinery. Widening social inequality and expanding farmer debt has led to issues like the suicide crisis of India, where hundreds of thousands of indebted farmers have killed themselves after becoming dependent on hybrid seeds, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and the machinery needed to produce crops at the scale required by the new economics of agriculture. Activists like Vandana Shiva have argued that 80% of the world’s population is actually fed by the produce of subsistence farmers rather than the industrialized agriculture highlighted in the Green Revolution. If this is true, then maybe the claims of the “revolution” are overblown.

Shiva also claims that the data she has compiled show that the number one factor in the rapid improvement of yields in India has been increased water use, not fertilizers or Borlaug’s “miracle seed”. Shiva says this increased irrigation is unsustainable, and cites studies showing a rapidly sinking water table across much of India. She further charges that by using language like “miracle seed”, the Green Revolution has become more a mythology than a scientific, data-driven reality.

Shiva is also an important activist against Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) who appears regularly on stage giving speeches and TED talks, or on television as an anti-GMO spokesperson. Although Borlaug’s dwarf wheat was not produced by the types of genetic manipulations currently used to produce GMO crops, some people still resent it as a human intrusion on nature’s processes. Borlaug, for his part, has stubbornly refused to believe there is a rational argument against the “miracle” he helped bring about. He received a Nobel Peace Prize, a Congressional Gold Medal, and a Presidential Medal of Freedom. Toward the end of his life he criticized people who questioned the Green Revolution as elitists who had never gone hungry, but he also admitted that although his contribution had helped save many lives, it had not created a Utopia.

Question for Discussion

- What were the pros and cons of the Green Revolution?