8.3 Winds and Climate

Paul Webb

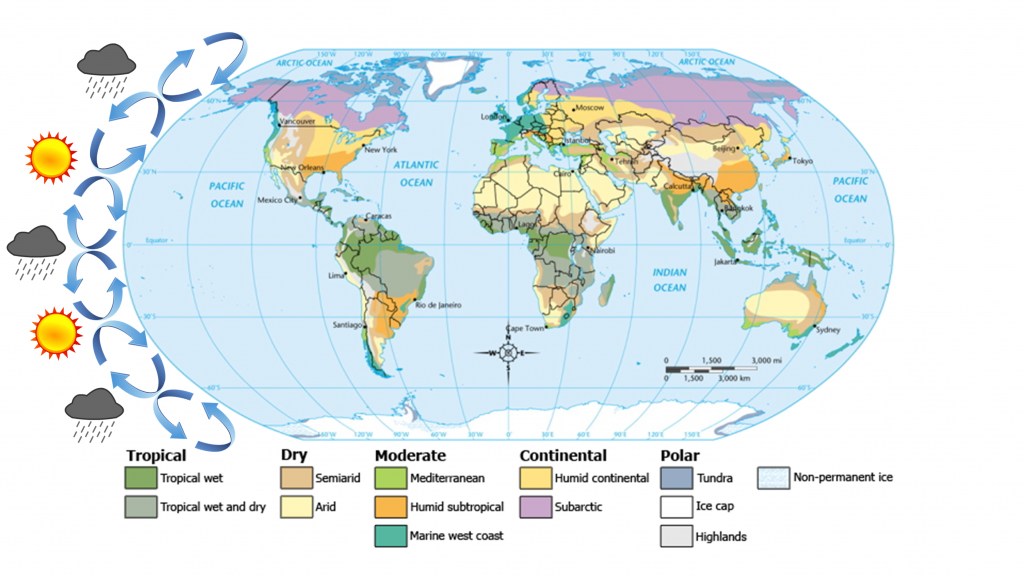

In the previous section we learned that rising air creates low pressure systems, and sinking air creates high pressure. In addition to their role in creating the surface winds, these high and low pressure systems also influence other climatic phenomena. Along the equator air is rising as it is warmed by solar radiation (section 8.2). Warm air contains more water vapor than cold air, which is why we experience humidity during the summer and not during the winter. The water content of air roughly doubles with every 10o C increase in temperature. So the air rising at the equator is warm and full of water vapor; as it rises into the upper atmosphere it cools, and the cool air can no longer hold as much water vapor, so the water condenses and forms rain. Therefore, low pressure systems are associated with precipitation, and we see wet habitats like tropical rainforests near the equator (Figure 8.3.1).

After rising and producing rain near the equator, the air masses move towards 30o latitude and sink back towards Earth as part of the Hadley convection cells. This air has lost most of its moisture after producing the equatorial rains, so the sinking air is dry, resulting in arid climates near 30o latitude in both hemispheres. Many of the major desert regions on Earth are located near 30o latitude, including much of Australia, the Middle East, and the Sahara Desert of Africa (Figure 8.3.1). The air also becomes compressed and heats up as it sinks, absorbing any moisture from the clouds and creating clear skies. Thus high pressure systems are associated with dry weather and clear skies. This cycle of high and low pressure regions continues with the Ferrel and Polar convection cells, leading to rain and the boreal forests at 60o latitude in the Northern Hemisphere (there are no corresponding large land masses at these latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere). At the poles, descending, dry air produces little precipitation, leading to the polar desert climate.

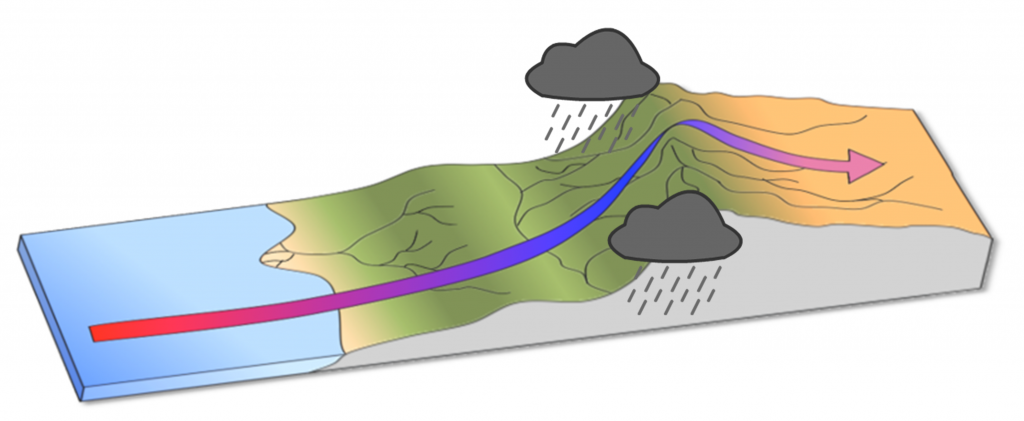

The elevation of the land also plays a role in precipitation and climactic characteristics. As moist air moves over land and encounters mountains it rises, expands, and cools because of the declining pressure and temperature. The cool air holds less water vapor, so condensation occurs and rain falls on the windward side of the mountains. As the air passes over the mountains to the leeward side, it is now dry air, and as it sinks the pressure increases, it heats back up, any moisture revaporizes, and it creates dry, deserts regions behind the mountains (Figure 8.3.2). This phenomenon is referred to as a rain shadow, and can be found in areas such as the Tibetan Plateau and Gobi Desert behind the Himalayas, Death Valley behind the Sierra Nevada mountains, and the dry San Joaquin Valley in California.

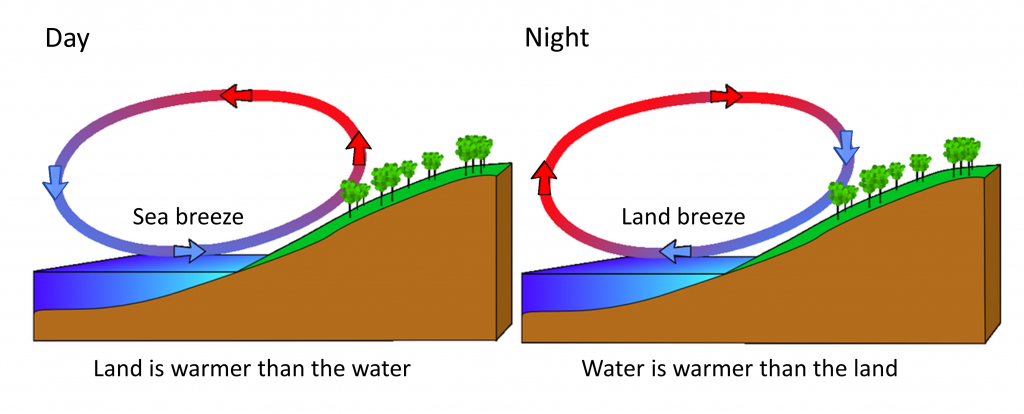

Rising and falling air are also responsible for more localized, short-term wind patterns in coastal areas. Due to the high heat capacity of water, land heats up and cools down about five times faster than water. During the day the sun heats up the land faster than it heats the water, setting up a convection cell of warmer rising air over the land and sinking cooler air over the water. This creates winds blowing from the water towards the land during the day and early evening; a sea breeze (Figure 8.3.3). The opposite occurs at night, when the land cools more quickly than the ocean. Now the ocean is warmer than the land, so air rises over the water and sinks over the land, creating a convection cell where winds blow from land towards the water. This is a land breeze, which blows at night and into the early morning (Figure 8.3.3).

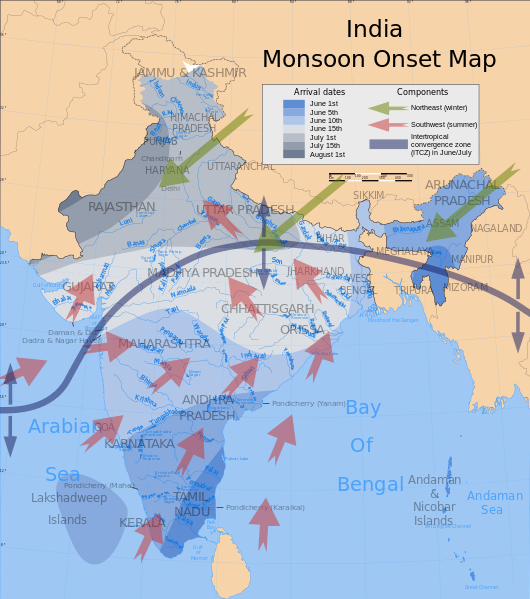

The same phenomenon leads to seasonal climatic changes in many areas. During the winter the lower pressure is over the warmer ocean, and the high pressure is over the colder land, so winds blow from land to sea. In summer the land is warmer than the ocean, causing low pressure over the land and winds to blow from the ocean towards the land. The winds blowing from the ocean contain a lot of water vapor, and as the moist air passes over land and rises, it cools and condenses causing seasonal rains, such as the summer monsoons of southeast Asia (Figure 8.3.4).

a rotating region in a fluid in which upward motion of warmer, low density fluid in the center is balanced by downward motion of cooler, denser fluid at the periphery (4.3)

arid conditions behind a mountain range, as rising air on the other side of the mountain caused rain, leaving only dry air to descend back down the mountain (8.3)

the amount of heat needed to change a substance’s temperature by one degree (5.1)

winds blowing from the ocean towards the land (8.3)

winds blowing from land towards the ocean (8.3)