7.3 Factors Influencing Production

Paul Webb

For terrestrial plants, many factors affect productivity, including light, temperature, nutrients, soil, and water. For phytoplankton, soil is obviously not needed, and water availability is not an issue. Temperature is generally more stable in the ocean than on land, so for phytoplankton, productivity comes down to the availability of light and nutrients.

Light

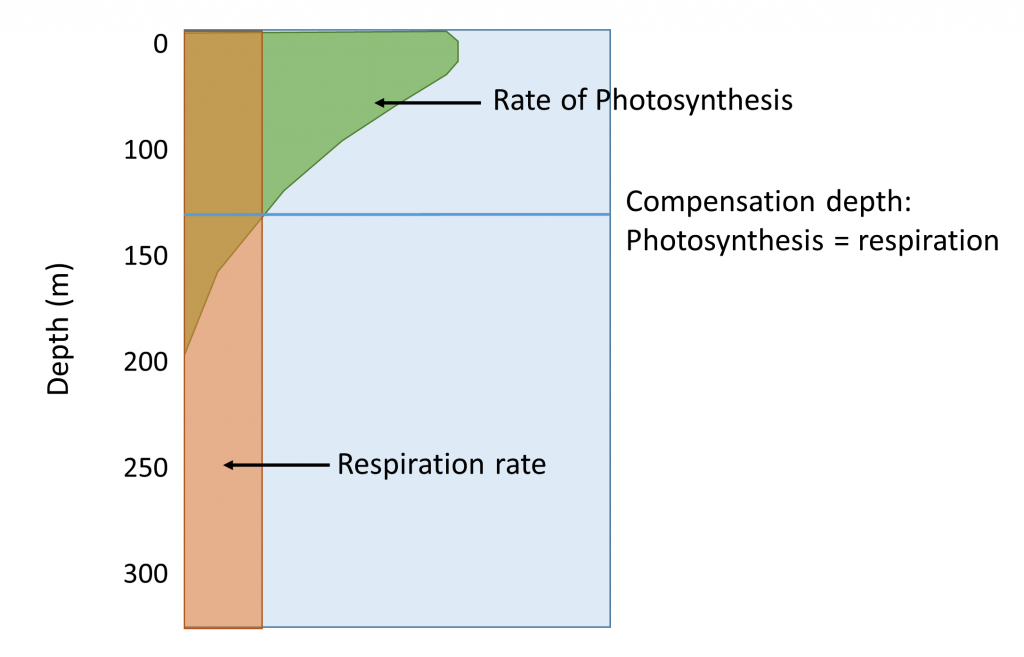

Since light is vital for photosynthesis, phytoplankton and other primary producers are limited to the uppermost layers of the ocean where light is abundant enough to sustain the reaction. As depth increases, light intensity decreases until there reaches a depth where photosynthesis can no longer occur (Figure 7.3.1). The region through which sufficient light for photosynthesis can penetrate is called the photic or euphotic zone, which extends down to about 200 m (section 6.5).

In addition to undergoing photosynthesis, phytoplankton also respire, consuming some of the organic compounds they produce. Rates of respiration are not light dependent, and respiration occurs at all depths and light levels. Therefore, as depth increases the rate of photosynthesis declines as light is diminished, until a point is reached where the rate of photosynthesis equals the respiration rate (Figure 7.3.1). This depth is the compensation depth, and it marks the lower level of the photic zone, and represents the depth where net primary production ends. Below this depth, there is net respiration.

Nutrients

Nutrients are required by all of the marine primary producers. The major nutrients required by phytoplankton are nitrogen and phosphorus, in the forms of nitrate NO3–, nitrite NO22-, ammonium NH4+, and phosphate PO43-. Many phytoplankton, particularly the diatoms, also require silica, SiO2, for shell formation. All of these nutrients occur in very small amounts in seawater, so they are often the limiting factors for phytoplankton growth in most situations, particularly the nitrogen compounds. For example, agricultural soil contains 0.5% nitrogen in the upper meter of soil, while surface ocean water contains about 0.00005% nitrogen, 1/10,000 the amount in soil.

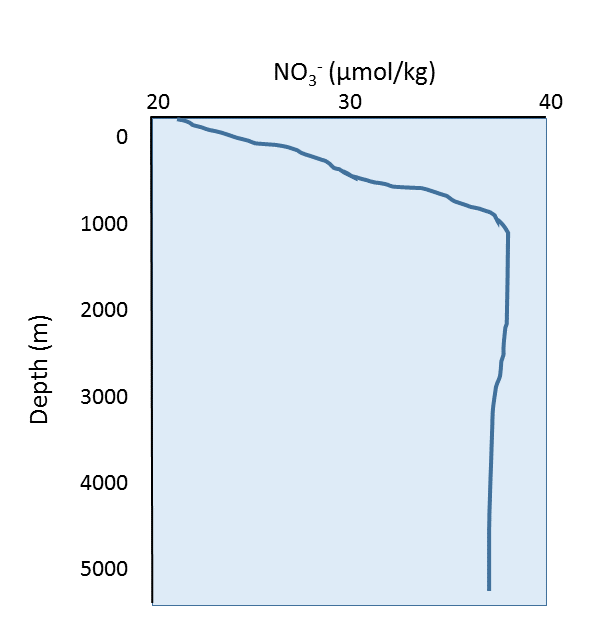

As we saw in section 5.6, nutrients are not distributed evenly throughout the water column (Figure 7.3.2). Near the surface nutrients are quickly utilized by phytoplankton as they become available, so surface waters are nutrient-poor. But as the phytoplankton are consumed or die they are recycled into particles of organic matter, such as fecal pellets or carcasses, that sink into deeper water. Once in deep water, decomposition of these materials releases the nutrients back into the water column. Because there are no producers to utilize them at depth, nutrients are more abundant in deeper water.

These deep water nutrients are out of reach of the phytoplankton at the surface. The thermocline and density stratification of the water column generally prevents the nutrient-rich deep water from mixing with the surface water. However, under certain conditions this nutrient-rich deep water may be brought to the surface through the process of upwelling (see section 9.5). Where upwelling occurs there is usually high productivity as the phytoplankton can take advantage of the input of nutrients.

in the context of primary production, substances required by photosynthetic organisms to undergo growth and reproduction (5.6)

drifting, usually single-celled algae that undergo photosynthesis (7.1)

the production of organic compounds from carbon dioxide and water, using sunlight as an energy source (5.5)

the upper regions of the ocean where there is enough light to support photosynthesis; approximately 0-200 m; also called the euphotic zone (1.2)

the upper regions of the ocean where there is enough light to support photosynthesis; approximately 0-200 m; also called the photic zone (1.2)

the depth where the rate of photosynthesis equals the rate of respiration (7.3)

total primary production minus the organic compounds used up by respiration by the producers (7.1)

photosynthetic algae that make their tests (shells) from silica (7.2)

a region in the water column where there is a dramatic change in temperature over a small change in depth (6.2)

process by which deeper water is brought to the surface (9.5)