5.6 Nitrogen and Nutrients

Paul Webb

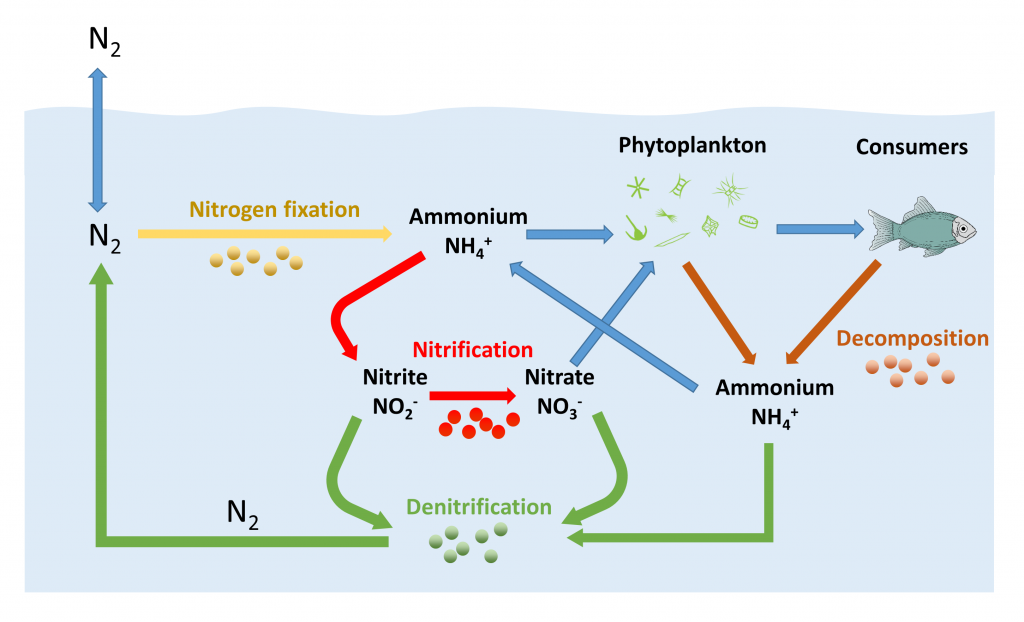

Nitrogen is the most abundant gas in the atmosphere, and like the other atmospheric gases it dissolves into the surface layers of the ocean. But most marine organisms cannot directly utilize dissolved nitrogen in the form in which it exists in air (N2), so it must first be converted into other nitrogenous products by marine bacteria (Figure 5.6.1). Some bacteria (cyanobacteria) take the dissolved N2 and convert it into ammonium (NH4+) through nitrogen fixation. Some of this ammonium can be used directly by phytoplankton, but the majority of it is converted by bacteria into nitrite (NO22-) or nitrate (NO3–) through the process of nitrification. Nitrate is the main nitrogenous compound utilized by primary producers in the ocean; it is a major nutrient required for photosynthesis. Note that in this context, a nutrient refers to a chemical needed to support photosynthesis and primary production. It does not refer to the nutritional needs of consumer organisms. The nitrogen taken in by phytoplankton gets passed on to consumer organisms, and then gets returned to the ocean through decomposition of wastes and organic matter as these organisms die and sink into deeper water. Finally, the ammonium, nitrate and nitrite can undergo denitrification by yet another group of bacteria and get converted back into N2, which can reenter the cycle or be exchanged with the atmosphere (Figure 5.6.1).

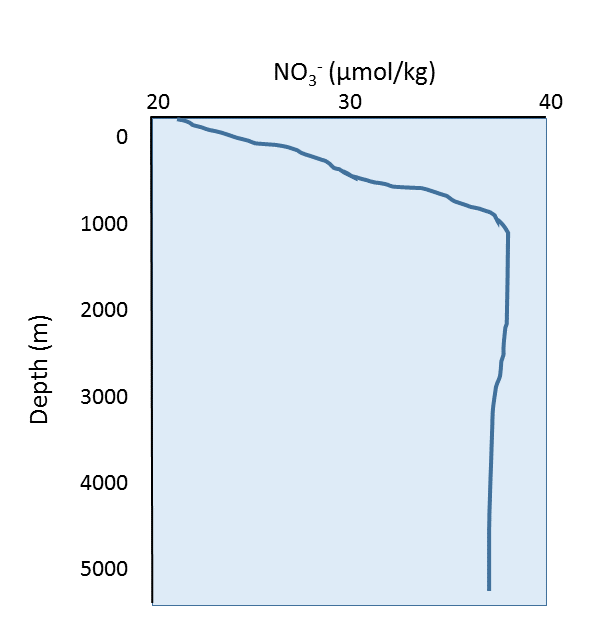

Since nitrate is one of the most important nutrients, for now we will focus only on nitrate as we discuss general nutrient patterns in the ocean. A representative nutrient (nitrate) profile is shown below (Figure 5.6.2). Since nutrients are rapidly used in biological processes, they are non-conservative, and their concentrations vary regionally and seasonally. Nutrient concentrations are low at the surface, because that is where the primary producers are located; the nutrients are rapidly consumed and they do not have the chance to accumulate. Nutrient levels increase at depth, as they are no longer being consumed by producers, and they are being regenerated through the decomposition of organic material by bacteria.

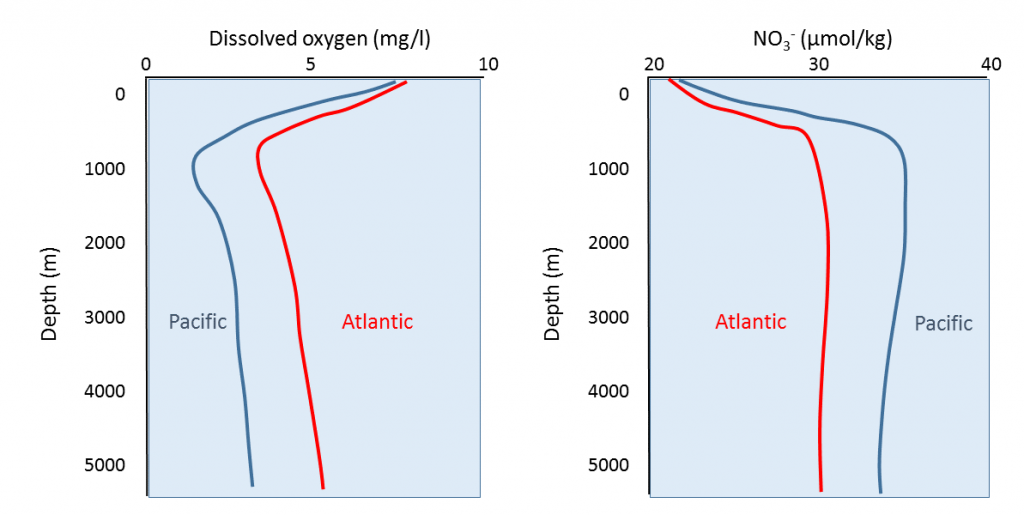

Comparisons of nutrient and dissolved oxygen profiles between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans reveal some interesting differences (Figure 5.6.3). In general, the Atlantic has more dissolved oxygen but lower nutrient concentrations than the Pacific. Water masses form in the North Atlantic that are very cold and dense, so the water sinks to the bottom. This water will then spend the next thousand years or more moving along the seafloor from the Atlantic, to the Indian, and finally into the Pacific Ocean (see section 9.8). This water is initially oxygen-rich surface water, and as it sinks it brings oxygen to the deep seafloor. As the bottom water moves across the ocean basins, oxygen is removed through respiration and decomposition, and by the time it arrives in the Pacific it has been depleted of much of its oxygen. At the same time, decomposition of sinking organic matter adds nutrients to the deep water as it moves through the oceans, so nutrients accumulate and the Pacific water becomes nutrient-rich. Comparison of the ratios of oxygen to nutrients in the deep water can therefore provide an indication of the age of the water, i.e. how much time has passed since it initially sank from the surface in the North Atlantic. Water with a high oxygen and low nutrient content is relatively young, while older water will have less oxygen but higher nutrient concentrations.

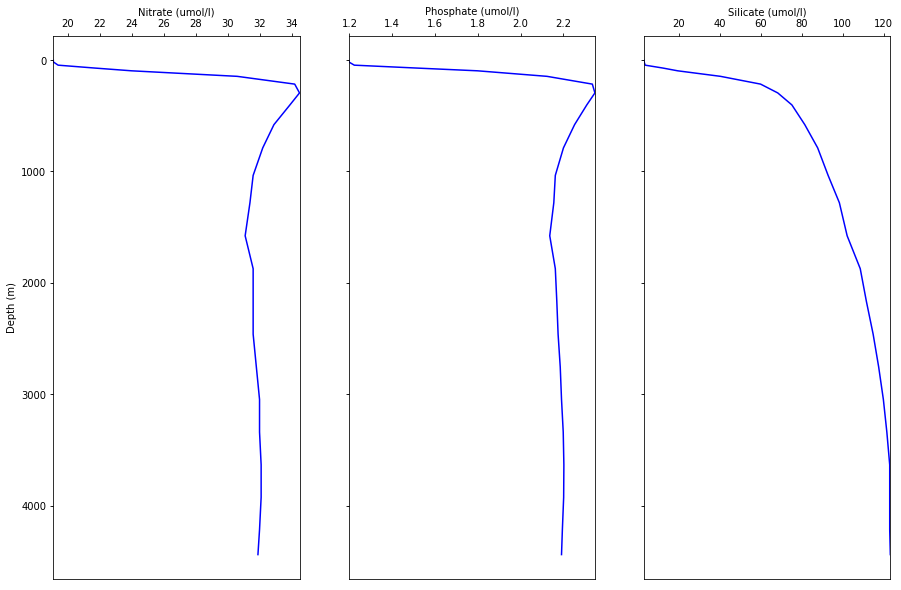

Other important nutrients, such as phosphate and silica, show similar patterns to nitrate (Figure 5.6.4), and will be discussed in the section on primary production (Chapter 7).

drifting, usually single-celled algae that undergo photosynthesis (7.1)

in the context of primary production, substances required by photosynthetic organisms to undergo growth and reproduction (5.6)

the production of organic compounds from carbon dioxide and water, using sunlight as an energy source (5.5)

ions in seawater whose proportions fluctuate with changes in salinity (5.3)