Chapter 8: International Relations

International Relations

Dr. Elsa Dias and Dr. Rick Foster

Chapter 8: International Relations

No war is commenced or, at least, no war should be commenced if people acted wisely, without first seeking a reply to the question, What is to be attained by and in the same? … we shall have to grasp the idea that war, and the form which we give it, proceeds from ideas, feelings, and circumstances which dominate for the moment … war may be a thig which is sometimes war in a greater, sometimes in a lesser degree.[1]

Learning Objectives

Students will be able to:

- Identify the various international relations theories (realism, liberalism, radical theories, constructivism, and feminism)

- Analyze global issues through an International Relations perspective

- Evaluate topics as a global citizen

- Develop an understanding of the role nation-states play in the international system beyond their own geopolitical space

Introduction

This chapter will briefly demonstrate to students the intersection of theory, history, practice, analysis, and predictability in an ever-evolving international system with diverse and complex actors. International relations’ contribution to political science has been vast in both academia and among practitioners. For example, the work of J. David Singer in the War Correlates[2] illustrates these relationships. International relations broadened the research in political science, in particular, its understanding of state to state relations and in foreign policy. Human security has moved beyond national borders into the international system and the complexity of the issues requires collaboration and multiple actors. Human security is intrinsically political and political science methodologies along with international relations provide for effective analysis while looking for solutions.

History

The Peloponnesian wars (431-405 B.C.) between Sparta and Athens were about balance of power and tensions between the two city-states and their respective leagues, the Delian League or the Athenian League, and the Peloponnesian League. Besides the great strategic game described by Thucydides, the leadership of important men like Pericles and Lysander and the role of Persia are some of the elements that international relations scholars can use for a historical analysis. The alliances are critically important for one’s understanding of the international system. A Multipolar system is exemplified by the ‘constitution of the Peloponnesian League’ (550-366 B.C.). The league’s constitution provides for how alliances worked between Sparta and its allies. Alliances were important to avoid war and to strengthen their position in relation to a common enemy. The following is an example of such an alliance:

I.(d) Each ally enjoyed, in theory, complete internal autonomy, but took an oath ‘to have the same friends and enemies as the Spartans and to follow the Spartan withthersoever they may lead’, and was consequently subject to Spartan dictation as far as foreign policy was concerned.[3]

3. During a war, Sparta was always in complete control of all military operations, by land and sea; and it was she who decided what campaigns would be conducted and provided the commanders.[4]

In order to hold her alliance together, Sparta on her side had to defend her allies from outside attack, whether from Argos or from beyond the Peloponnese, give them ‘freedom and autonomy’ (in a very special sense, as we shall see in a moment), and attach them to herself by making them acquiesce in their submission to her hegemony. If she broke her treaty obligations, the allies concerned, in theory, would automatically be released from theirs; although, of course in practice they might not dare to repudiate their treaties and thus ‘revolt’ from Sparta: This would depend on their strength relative to Sparta’s and the external situation at the time.[5]

Another historical element worth mentioning is the Thirty Years War and the resulting Treaty of Westphalia (1648). The result was a separation of church and state, recognition of state sovereignty, and geopolitical borders.

The European religious wars of 1618-1648, known as the Thirty Years War, refocused power away from religious authority, the pope, to the states, kings. The assertiveness of kings to gain power promoted a new definition of both nation-state and sovereignty. The historic consequences of the Thirty Years War are multilayered. By concentrating power on the state, kings learned to: 1) amass power and to give birth to an era later known as absolutism; 2) respect geopolitical borders in Europe and to assert their power in far-away lands, a process called colonialism; 3) rule with the concept of sovereignty in mind; and 4) respect the emergence of nation-states. Kings have secular power over “their” people and the church has power over their salvation—separation of church and state. Building a national military, pulling power away from lords, solving border disputes, building trade, protecting rights of individuals, facilitating the movement of peoples were key issues that kings learned how to do diplomatically while demonstrating that they did not fear religious retaliation from Rome. The use of force to protect the state, geopolitical borders, resources, and population is now the sovereign’s (king) responsibility. The idea that a feudal lord wants a castle by the sea to vacation in during the summer months was altered with the Treaty of Westphalia. Feudal rebellions were crushed and international affairs were now part of the king’s power as executive, as chief diplomat, and as foreign policy maker.

Showing allegiance to the king not feudal lords became standard, and post-1648 it was the modus operandi for the state’s economic and political life, or even perhaps, for its survival. As a result of the Thirty Years War and the Treaty of Westphalia, countries increased diplomatic ties with each other, not via Rome. Who had power? What alliances shall be drawn? What helped shape international law? Common interests in the high seas led to the Law of the Seas and management of piracy. Alliances were flimsy. A multipolar system was established with states possessing a naval power, and as such, these states were perceived as powerful. While domestic power in terms of “military boots” on the ground was key, international affairs was shifting to challenge colonial powers like: Portugal, Spain, Britain, Holland, France, Italy, and yes, even Denmark. States started to demand their fair share of colonies and access to the seas. Previously, the pope had divided the world with the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 between the Portuguese and the Spanish. The Westphalian world created a new challenge, because colonial expansion depended on the strong and strategic naval capacity of states.

Multipolar system

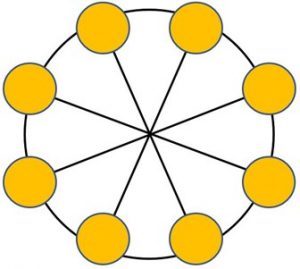

A multipolar system occurs when states create alliances among themselves that last only until one state perceives that it no longer benefits from that alliance. Switching alliances is expected among states in the international system.

England and Portugal are known to have the oldest alliance in Europe. States made alliances with each other as long as they perceived a benefit. If another state offered a “better deal,” alliances were likely to shift. This system was in place until the end of World War II. The multipolar world is best described as two countries or more with power and capacity to act and to make alliances that have short- to medium-term characteristics. The effects of various historic events like revolutions, in the United States (1776) and in France (1789); dynastic interests during the 18th and 19th centuries; the continental blockade and the Napoleonic wars 1807-11; the concert of Europe (Russia, Prussia, Austria, Great Britain); and the Berlin Conference 1884-85 (European claims on Africa) all demonstrate how alliances and state interests along with kings’ interests, make the multipolar system critically complex. The multipolar world starting with the Peloponnesian wars and the shifts of alliances until World War II demonstrates the durability of this system. The various historical periods of the multipolar system show how the system works and evolves.

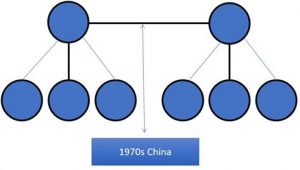

Bipolar system

When World War II ended in 1945, the historical multipolar system with its complex structure of alliances, gave room to a bipolar system with two super powers, the United States (U.S.) and the Soviet Union (USSR). At the end of World War II, U.S. and USSR stood with power in the following areas: military, economic, political, social capital, and values. The period between 1945-1989 was called the Cold War. The world was struggling to make sense of what World War II had brought to their doorstep. While fascism did not end, Nazism and its atrocities did. Empires embarked on a decolonization process that would last decades. Peoples were gaining consciousness of their sovereignty and of self-governance. States were trying to rebuild, reaffirm their position, and reclaim power in an anarchic international system. The bipolar system demanded states to take sides with either the U.S. or with the USSR. The Cold War was a time to pick your battles. States formulated their alliances based on economic, military, and social interests. For example, political systems, like dictatorships, were overlooked as long as U.S. interests were protected and U.S. national security was prioritized. The U.S. and USSR created an arms race, a space race, and a technology race (perhaps, it was more like a technology gap.) The two powers had allies, willingly or not, to help advance their power and interests in the international system. The U.S. and allies created NATO in 1949.[6] In 1955 as a response to NATO, the USSR created the Warsaw Pact.[7] Military arrangements were clearly important and a source of demonstrated power. During the Cold War, peace between the two superpowers was critically maintained as evidence suggests by the number of proxy and limited conflicts fought in places like Greece, Korea, Vietnam, Angola, Grenada, Guatemala, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Afghanistan to name only a few. The bipolar system worked to create stability and relative peace as no world war was fought between the period of 1945 to 1989. The bipolar system was made possible because economic systems supported the building up of militaries, and the development of technology created competition beyond the military. Nuclear power and ballistic systems helped support deterrence between the two superpowers and their allies. During this time, security distrust along with economic competition and differences in values produced tensions, which created misconceptions and misperceptions that would influence foreign policy for decades. Détente evolved during the Nixon administration. This is known as a period of relaxation of tensions between the two superpowers. Détente led to disarmament discussions and the SALT treaty in the 1980s. How does the Cold War end? With a wall, a brick in the wall, the Berlin wall. The symbolism of the Berlin Wall being torn down in 1989 is important. Gorbachev negotiated with the west. Gorbachev envisioned a more open society, and perestroika and glasnost were his policies to achieve the society he thought necessary for that time. Popular culture had its impact as well. The emergence of popular culture and figures like Sting and his song “Russians”, the Culture Club with their song “The War Song”, the film “Judgment in Berlin” (1988) among others helped to open East-West relations. The international system was going through another change during this time. The fall of the Berlin wall and the establishment of the Russian Federation in 1992 left the U.S. standing as a hegemonic power. A unipolar international system was beginning to emerge.

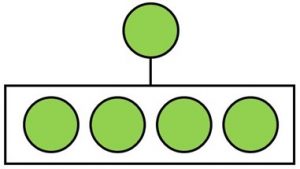

Unipolar system

The unipolar system is defined as having a single state with power and acting with hegemonic capacity. This period lasted from the years of 1989 to 2000. In the unipolar system, the U.S. was the sole superpower. Some scholars have challenged the hegemonic position of the U.S. Othe

r scholars have suggested that states turned to regional responses and diverted their attention regionally (an increase in regionalism, or reginal al

liances among states). Regionalism offered states the ability to fill a power vacuum. The unipolar system saw a new challenge as the “pool” of allies increased through regional alliances. The economic system changed; trade demands and expectations did as well. During the 1990s, the U.S. as de facto holder of hegemonic power, was challenged by unexpected states. The following are examples of how the U.S.’ power was chipped away: Japan asking the U.S. to withdraw its troops and Turkey challenging the U.S. in the Middle East in 2003 and in 2019. In 2003, Turkey first denied U.S. airspace, then they gave airspace permissions but denied the use of Turkish bases for an attack on Iraq. Further, Turkish President Erdogan made a bilateral arms deal with Russia in 2019.

The United States has also lost some of its hegemonic power as suggested by Carranza in regard to MERCOSUR[8] and FTAA[9] agreement in Latin America: “The Miami Trade Ministerial Conference illustrates the limitations faced by the United States in its attempt to reassert hegemony in Latin America. […] Brazil and MERCOSUR successfully managed to balance U.S. power. […] The history of the FTAA negotiations shows the difficulties faced by the United States in consolidating hegemony over Latin America and the important role played by MERCOSUR as a counterweight to the exercise of U.S. structural power in the region.”[10] The U.S.’ unipolarity and hegemony were challenged in the first years of the 2000s. Regionalism started to form during this period. China started to concentrate its economic power with expansion of military power alongside a space race. China competes with Japan on a number of issues like South China Sea territory, and the cement market. The unipolar system of the 1990s is critically challenged by various events like the United States’ War on Terror, the Great Recession of 2008, challenges to political systems with the Arab Spring, and more recently the emergence of populist governments challenging democracy. Polarity in the international system has been imagined and reimagined as global circumstances demand. History allows for examples to be discussed, but theoretical approaches allow for analysis and prediction.

Theories in International Relations

What is the purpose of international relations theories? Why should they be used? Most political scientists have been trained to admire and promote theories of international relations, in part because these theories provide structure and allow for explanations. Meanwhile, students want to know what is happening in the world: why states’ reactions and behavior differ when faced with the same problems? And in some cases, students want to know what they can do to solve a problem. How do students and their interests fit into the picture? Regardless of the level of altruism from students, political scientists remain firm that theory provides for a means to explain and make sense of wars, international law, genocides, famine, trade, environmental problems, and pandemics, to mention a few of the issues that affect one’s life in this very intensely global world.

Theories provide for a systematic and independent process, which allows investigators to analyze and predict phenomena. Using theories helps to legitimize ones studies and helps frame the study, the analysis, and the predictions. In this way, theories provide scholars with a “framework” to interpret phenomena. Theories are a tool of analysis. Why include theories, such as the following: realism, liberalism, constructivism, radical theories, and feminism?[11] These theories offer competing ideas and approaches. They are important because they reframe global issues and their complexities. The theories included therein are well-established theories and are well accepted by scholars of international relations. Most importantly, these theories are studied and introduced to students at most undergraduate institutions. In international relations, theories focus mostly on the state as an actor in an anarchic international system.

Classical Realism

Realism offers a state level theory that proposes that the central actors in a global context, are states seeking power. Realism argues that the battle for power and preserving power is critical for state survival. States seek to increase power—both tangible and intangible. In this scenario, states amass power at the cost of a perceived enemy. When one state has power and another state does not, that constitutes a legitimate threat. Realism allocates human characteristics like selfishness, greed, aggression, and insecurity to states. This is because the individuals who govern states have those behaviors, and therefore, cannot be trusted. While realists insist that war is more likely to prevail than peace, long-term durable peace is difficult to ascertain. Two things are important for peace to be obtained. First, there must be a balance of power (U.S. and USSR during the Cold War), and second, is the cost-benefit of war. Balance of power is executed when two or more states have near identical power in terms of capacity, capability, and resources. Cost-benefit analysis of wars occurs when states either go to war because they predict that they can win, or, they do not engage in conflict because victory is uncertain.

Realism Authors: Thucydides, Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, Carl von Clausewitz, Hans Morgenthau, George Kennan, E. H. Carr, Henry Kissinger

Neorealism Authors: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Kenneth Waltz

Liberalism

Liberalism is another state level theory centered on cooperation, international law, international trade, international institutions, and human security. While liberalism recognizes and thrives on cooperation and diplomacy, it also sees the benefits of competition. Contrary to realism, liberalism acknowledges that individuals have a desire to improve the state of the human condition and to promote a just society. It also acknowledges that individuals are rational beings and believes that laws are needed to promote cooperation. Shared values offer alternatives to conflict, including war. Within liberalism, democratic peace theory argues that because of shared values, culture, and norms, liberal democracies are less likely to go to war with other democracies. However, this does not stop liberal democracies from going to war with states that have opposing ideologies. With liberalism as a theoretical approach, international law is enforceable. Also, this theory promotes social justice issues like human rights, ecological issues, and cultural exchanges. The existence of U.S. and USSR cooperation over arms control since the 1980s demonstrates how diplomacy works even when military concerns and power are at stake. As a theory, liberalism supports the use of international conventions, like the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (1946), the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water (1963), or the Convention on Biological Diversity (1992). Under the umbrella of liberalism, international institutions are used to mediate conflicts—like the World Trade Organization mediates trade and the United Nations (UN) promotes preventive diplomacy.

Full Text: An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation by Jeremy Bentham

Today, the international community has embraced non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as allies for the creation of cooperation and human security.

Liberalism Authors: John Locke, Jeremy Bentham, Adam Smith, Joseph Schumpeter

Democratic Peace Theory: Bruce Russett

Constructivism

This theory adds state behavior to the context of the state’s characteristics, because each state has its own uniqueness: values, history, institutions, political system, social landscape, economic system, and religious practices. These elements affect how the state acts in the international system, through its foreign policy. For example, the United Kingdom’s (UK) exit from the European Union (EU), known as Brexit, demonstrates that as a unit the UK has a set of values and social landscape that are in contrast with continental Europe. Brexit is an example of clashing identities and interests. The concept of state interest is socially constructed based on the state’s unique characteristics. States socialize other states and in turn they are socialized by international organizations, like the UN and the EU. The acceptance of international law by states and inclusion of international conventions, such as the Third Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War (1949), demonstrates how states are socialized by accepting ideas that otherwise they would have not adopted and how international organizations promote cooperation by adoption of international law.

Constructivism Authors: Alex Wendt, James Der Derian

Radical Theories

Generally identified as Marxist in nature, these theories expand from Marx, to Lenin, and to neo-Marxist theorists, like dependency theorist Cardoso. Traditionally, Marxism focuses on class (state and society), while Marxism-Leninism (and Neo-Marxism) turns its focus from the state to the international system. The Marxist idea of class struggle over the ownership of the means of production (e.g. coal mines and factories), and the struggle between the proletariat (the laborers) and the bourgeoisie (the owners), transfers to the international system by studying countries. This antagonism grows domestically until the working class, the proletariat, gains consciousness of its needy position and through a revolution, takes over the government and regains control of the means of production, thus promoting domestic equity by the distribution of goods and services. The proletariat initiates an international moment of revolutions. This process will bring international consciousness to the following issues: 1) labor conditions of individual workers; 2) bourgeoisie acquisition of resources; 3) inequity in the distribution of goods; and 4) the disadvantage of trade relations in colonial times and post-colonial relationships among states (e.g. Marx demonstrates the disadvantaged position of India, relative to England).

Marxism-Leninism, and to a certain extent, neo-Marxism, offer distinct insight into international relations by exploring state relations through dependency theory (Cardoso), banking (Luxemburg), and system theory (Wallerstein). The prevalence of corporations, multinational corporations (MNCs), and transnational corporations (TNCs) dominating trade relations, services, and banking between rich and poor countries demonstrate the inequities in the international system. MNCs take advantage of the international system by exploiting poor countries’ labor and natural resources because these countries lack the political and economic capacity to assert and to protect their disadvantaged position, particularly in trade.

Marxism-Leninism looks at the international system as anarchic. The anarchic nature of the international system allows for states to create hierarchic economic and political relations among themselves in part due to economic domestic conditions. In this instance, the state has shifted its interests from manufacturing to finance capital and banking. Finance capital is internationalized, and in Lenin’s terms this equals imperialism. The Vanguard Party envisioned by Lenin would lead the proletariat through liberation. In disagreement with Lenin, Luxemburg suggested that domestically this liberation is more organic and not dependent on the hierarchy of a party. Dependency theorists like Cardoso argued that it was in the interest of the core states (1st world) to maintain the status quo. The periphery states (3rd world) were at a disadvantage and were dependent on the prices of raw materials and labor markets to be able to satisfy the core states’ production needs.

Radical Authors: Karl Marx, Nikolai Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Mao Zedong, John A. Hobson, Immanuel Wallerstein, Fernando Cardoso

Feminism

Feminism focuses on the absence of women’s voices in international relations. Feminist theory provides for women’s voices that are absent from theorizing, decision-making, or even from daily activities typically performed by women. Gender as a category of analysis is also included. Feminism sheds light on the absence of women’s perspectives in decision-making. Equally important is women’s inclusion in areas of war and peace. For example, the systematic rape of women in 1992-1995 during the Bosnian War finally went to the International Criminal Court (ICC), where women were able to present their cases of rape and torture. The result was that rape is now a war crime and a crime against humanity. The Nuremberg trials and the Tokyo trials, post- World War II, in contrast, side stepped women. In the case of Japan, Korean women who endured sexual assault and servitude during World War II were labeled as ‘comfort women for Japanese soldiers.’ Due to the courageous voices of Bosnian women, the work of international judges, prosecutors, and investigators, the sexual assault perpetrated on women and girls during the Bosnian conflict now constitutes a war crime. This new jurisprudence has established a safe place for women’s voices to heard and protected. Now there is a process for accountability. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993-2017) was created to prosecute and bring accountability for acts performed during war times in Bosnia, including acts performed specifically against women and children. Human rights have now been extended to all those who suffered rape, sexual torture, and other forms of persecution during war. In this context, rape and all other sexual actions perpetrated against women and children, and in some cases against male civilians, are punished and some level of justice is realized.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia

Feminism Authors: Cynthia Enloe, J. Ann Tickner

Theories are important for the study of international relations, yet they need further contextualization by integrating them with levels of analysis.

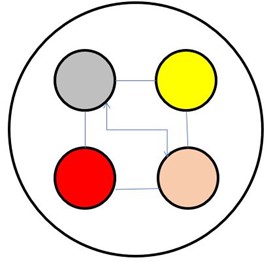

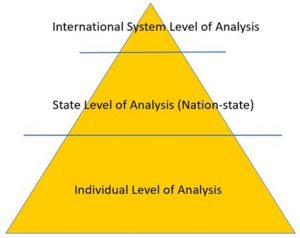

Levels of Analysis

In international relations, levels of analysis allow for a better understanding of states’ behaviors in various complex scenarios. Levels of analysis help international relations scholars better understand and analyze how decisions are made and the effects of perceptions in state relations. International relations scholars recognize three levels of analysis: Individual, State, and System. Each level has its own characteristics and impacts.

Individual Level of Analysis

This level of analysis focuses on individuals and their contributions. Individual level of analysis uses domestic political atmosphere as a barometer for what actions might be expected from that state. Domestic conditions affect how leaders and decision-makers participate in foreign policy. A leader’s perception of a situation may promote peace or conflict. An example would be how President Trump perceives trade relations with China. The result has been a trade war that has affected many areas of the U.S. economy. A leader’s personality is equally important. Gandhi was able to return India’s to independence in 1947 in part because of his actions and persona. He was charismatic and respectfully defiant of British rule of the Indo-subcontinent.

Some important variables to consider for the individual level of analysis include the following:

- Decision-making

- Awareness of domestic public opinion and support

- Personality (or lack thereof)

- Perception

- Actions and choices

Individuals with different levels of resources, access, and power have different perspectives about their state’s survival in the international system.

Actors or participants: politicians, policy makers, academics, popular leaders, grass-root leaders

Examples: Ronald Reagan, Mikael Gorbachev, Nelson Mandela, Noam Chomsky, Gandhi, and Greta Thunberg.

State Level of Analysis

Domestic politics shapes how states perform internationally. Is the government a democracy or an authoritarian regime or a transitioning democracy? These are important issues to consider as different regimes have different expectations that can either support international negotiations or hinder them. Besides the type of regime, economic systems are also important to consider how states participate. The type of economic system—whether capitalist, socialist, communist, or hybrid constrains how states negotiate in trade, accept foreign direct investment (FDI), economic development, and equitable access to goods and services. The ability of a state to see how it can benefit from a situation potentially promotes or hinders an international negotiation. For example, the current negotiations between the U.S and North Korea can be perceived as a hindrance to North Korea, because nuclear weapons are a bargaining chip for its regional power. The level of domestic participation in areas of legitimate government, political transparency, free and open elections, free press, and the opportunity for individuals in civil society can be predictive elements of state behavior in the international system.

States have tangible and intangible variables that scholars have used to measure and predict a state’s actions. The following are examples of each:

Tangible Variables: population and demographics, military capability, natural resources or lack thereof, geography, geopolitical borders, and history

Intangible Variables: culture, norms, values (e.g. human rights, promotion of equality and opportunity, and civil liberties).

These variables can be useful in placing countries in the international system. It is also a means used to rank countries, for example, the index of … [provide example or examples].

International Level of Analysis

In general, international relations scholars accept that the international system is anarchic, because there is not an overarching institution that is above the states that offers deterrence and punitive enforcement for non-compliance. International interaction among states is multifaceted: regional, bilateral, international governmental organizations (IGOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), MNCs, etc. Power is an important issue because of the anarchic nature of the international system. Distribution of power is limited, because of the inequality among states. In the international system, displays of power are identifiable. For example, hard power consists of coercive power, threats, and the use of negative incentives. Many times, states use military power as a form of coercive action.

John Mearsheimer and power; the following video describes power:

Or click here to watch the video!

Soft power is an example of power exercised by states like persuasion. States measure their power in a context. Soft power can be exemplified on how states use their position in the international system. For example, exchange students, study abroad programs, and international students, are all a means of cultural and educational exchanges that promote soft power.

Joseph Nye and power; the following video describes soft power:

Or click here to watch the video!

Power itself is not contested; what is a point of argumentation, however, is how power is measured, how it is executed, and how successful or not it is. It is therefore critical to study other actors and elements of the international system, like international law, international institutions, non-governmental organizations, to name a few.

International Law

International law helps define responsibilities of states and their behavior with each other. International law is not without its critics. International law was not able to stop either World War I or World War II. It is difficult to hold countries accountable and it lacks enforcement—as in the case of the 2003 invasion of Iraq forged by the U.S. and the coalition. Declarations, such as the Human Rights Declaration of 1948, are difficult to enforce or to provide for punitive action. This is because they are not law, and are therefore, not enforceable. Declarations are agreements based on values and accepted norms of behavior that reflect common ethical goals.

Violations of treaties and violations of accepted and codified law, are enforceable via sanctions and other punitive actions deemed necessary by members of the international community. International law provides for a framework as in the case of Antarctica with treaties and protocols Article: Antarctica shall be used for peaceful purposes only. It also stipulates procedure like in the case of Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1968 (NPT) Click here to read the treaty. For the most part, international law like the examples mentioned above, and treaties are categorized as customary law. Sub-areas of customary law are: humanitarian and peace law, law of war, law of diplomacy, and responsibility to protect (R2P). When it comes to issues covered by international law, they are diverse. A few of the many examples that could be listed are shown below.

The diversity of issues that have provisions and protections under international law demonstrate the willingness of the international community to manage and work with reciprocity and in ‘good faith’ to establish a common set of values. While self-interest continues to be key to how and to why a state chooses to follow international law and norm, the current system benefits cooperation.

International Governmental Organizations (IGOs)

The post-World War II world gained a slew of organizations designed to provide ample cooperation among states in an increasingly diverse international system. International organizations provide for arbitration in some cases and in other cases it offers expectations and predictability. International organizations like the United Nations (UN) Security Council vote on resolutions such as war. The UN was formed in 1945 at the end of World War II. The failure of the League of Nations after World War I and the subsequent World War II, twenty years later, provided for a strong argument to support the UN in 1945. The United Nations offers a chance for states to understand power, and for people to understand their right to self-government and sovereignty. The UN was created with six bodies: The General Assembly with 193 members (today’s number), the Security Council (five permanent members—United Kingdom, United States, Russia, China, France, and ten rotating non-permanent members voted in by the General Assembly), Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), The Trusteeship Council, The Secretariat, and International Court of Justice (ICJ) United Nations: Main Bodies.

After World War II, six countries in Europe formed the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). This organization became essential for European economic stability post World War II by providing countries in Europe with more reason to cooperate than to defect. The European Economic Community (EEC) emerged, and by the 1980s the enlargement of the EEC proved that law making is stronger at the European Union (EU) than at the UN Article: The History of the European Union. Today, the EU is a power to counterbalance states like the United States and Russia. The EU has 27 member-states. The institutional bodies key to the function of a well-established economic, political, and social union are the following: the European Parliament, European Council, Council of the European Union, European Commission, Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), European Central Bank (ECB), European Court of Auditors, European External Action Service, European Economic and Social Committee, European Committee of the Regions, European Investment Bank, European Ombudsman, European Data Protection Supervisor, European Data Protection Board, and Interinstitutional Bodies EU Institutions and Bodies.

The UN has global reach along with International Monetary Fund,[12] World Bank,[13] The World Trade Organization,[14] and Interpol.[15] These organizations promote human security, policing action, military action (UN’s blue helmets), economic stability, and economic assistance. Their role is to facilitate interaction and exchanges among states and among peoples. Yet the increase of regional organizations offers an alternative to the concept of hegemony. The global presence of regional international governmental organizations (IGOs) like ASEAN,[16] AU,[17] the IAEA,[18] MERCOSUR, provide evidence of how regionalism have a legitimate place in the international system. Fluidity of relations appears to provide challenges that make for cooperation in a globalized world more likely to succeed. Regional and global cooperation provide an alternative to zero sum game. It is harder today for China to claim regional moral high ground when President Xi Jinping promotes domestic policies like “reeducation” of the Uyghur population in detention camps Article: Devastating leaks have deprived China of its main strategy to deflect mounting evidence of its mass oppression of Uighur Muslims.

The African Union’s work on COVID-19 provide for an example of regional collaboration when the declaration of April 16, 2020 states that: “Keeping the national borders open for food and agriculture commodity trade so as not to disrupt regional and interregional trade in food and agriculture products and inputs.”[19] Regional organizations are making attempts to manage this pandemic and developing strategies for regional and global inter-state cooperation as the African Union’s work demonstrates.

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

Since the 1990s there has been an explosion of NGOs with international interests motivated to act based on a variety of transnational issues. NGOs work to advocate, to lobby, to operationalize action and to engage in protest. Generally, NGOS are international actors that focus on one issue and to advance a cause. Some NGOs provide for goods and services to those in need, others do research, others provide for expertise, etc. The participation of NGOs in the international system transforms the landscape by working on issues that demand broad cooperation by multiple actors. This is particularly true when issues like malaria happen. Malaria affects disproportionately poor countries. Less-developed countries (LDCs) going through a malaria crisis have depended on NGOs like The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. NGOs like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation work to provide life-saving aid to populations in less developed states. In the process, partnership among international actors is necessary: “we can save millions more lives by addressing the high-burden countries, in partnership with affected countries, donors and technical partners. […] We also advocate for sustained and increased funding of malaria-related efforts by donor government and affected countries.”[20] This NGO provides for accountability in global governance as well as global partnerships. Human Rights Watch, not surprisingly, promotes human rights. One strategy it and other NGOs use is to embarrass states, and states can be sensitive to this strategy. Human Rights Watch provided low-level shaming in an article written by Maria Laura Canineu titled: “Brazil Needs More Pesticide Regulation, Not Less.” Canineu writes that:

Another pesticide found in samples of lettuce is atrazine, which the European Union banned in 2003 because it interferes with reproduction and human development, and may cause cancer. It’s legal in Brazil, though. […] One of the rights celebrated that say is the right to food, which includes the right to food safety. Another is the right to health, which depends on a decent, well-regulated food supply. Ensuring both these rights requires ensuring safe levels of toxins, bacteria, and other substances that can make food injurious to health.[21]

By pointing out the issues with food security and framing them as a human right, Human Rights Watch is putting Brazil, the state, on alert regarding the issue of food safety and food as human right. In this case, the NGO points out how the state fails to protect the nation (its population).

To provide a perspective of international activities, the following is a table that contains a few NGOs, some widely known IGOs, and some international conferences.

| IGOs | NGOs | Conferences |

| UN—United Nations | Doctors Without Borders | UN Women’s Conferences 1975, 1980, 1985, 1995 |

| EU—European Union | Reporters Without Borders | UN Environment and Development 1992 |

| ASEAN—Association of Southeast Asian Nations | Human Rights Watch | UN Human Rights 1968, 1993 |

| IAEA—International Atomic Energy Agency | International Rescue Committee | UN Human Environment 1972 |

| AU—African Union | Afghan Women’s Network | UN Climate Change Summit 2019 |

| MERCOSUR—South American Regional Economic Organization | Greenpeace | Doha Conference (2001, 2008, 2012) |

| League of Arab States | Caritas | |

| Global Forum on Sustainable Food and Nutrition Security |

The challenges in international relations regarding transnational issues require complex solutions and consistent state cooperation. Some solutions have been beneficial to many, such as the UN Millennium Development Goals.[22] States acting in their own interest, face challenges when human security and state security clash. Transnational issues demonstrate that clash and the challenges produced.

Transnational Issues: The Challenges

Interconnection among individuals has been growing due to people’s movement as well as broader access of technologies used for communicating. Transnational issues vary in time and space. Transnational problems are unpredictable. This promotes instability and uncertainty among states. Reactive actions have become the norm. For example, pandemics like COVID-19 demonstrate how difficult it is for states to prepare and how imperative it is for states to cooperate. Ultimately, some states have a reactive approach to problem solving, like the U.S. Another set of states such as Greece or Iceland has a proactive approach to the pandemic and the results of their actions when shared can benefit other states. The lack of global cooperation during COVID-19 has produced competition and hoarding of supplies. For example, in the United States, some of the states are competing in the global market for COVID-19 tests and PPE (protective personal equipment), like medical gowns and masks. This is in part because the U.S. was not prepared. South Korea, in contrast, has been proactive in sharing its resources, like COVID-19 tests. The World Health Organization (WHO) understands that epidemics and pandemics do not recognize geopolitics borders. WHO collects data, provides for predictive measures, and provides for expertise. If states are willing to collaborate, WHO can be a source of information for states to effectively manage global pandemics. Cooperation and disagreements are typical of transnational reactions among states. The following transnational issues, microcredit, cyber warfare, climate migrants, and water will be addressed next.

Microcredit

Microcredit has its proponents and its opponents. When Muhammad Yunus started to give small loans to Bangladeshi women, he did not predict how his efforts were creating a movement that would help many and would eventually lead to the creation of Grameen Bank. From the creation of Grameen bank to today, there are growing number of microcredit NGOs that provide help— mostly to women, children, and the poor in general. Criticism of microcredit is based on how it has not lifted people out of poverty. Microcredit also has its challenges with some organizations promoting cash transfers. Microcredit emphasizes return on capital investment and re-investment in the community, while cash transfers do not have an incentive to promote community partnerships. In theory, microcredit does the following:

- finances loans of a few hundred dollars

- promotes self-employment, and entrepreneurial skills

- allows for educational opportunities

- helps with housing

- provides for examples in the community

- leverages neighbor to neighbor micro-financing

- develops strategies for community engagement

Student Activity

Student Activity:

Compare and contrast two microcredit NGOs like Kiva https://www.kiva.org and Grameen Bank http://www.grameen.com . Answer the following questions:

- How do the two NGOs improve livelihoods?

- Compare information posted on the websites about the organizations’ board of directors, projects, funding, process for creating loans, where they operate, who has received loans, percentage of both loans in repayment and default, etc.

- How does microcredit improve economic growth?

- What is the impact of the loans on communities?

Student Activity

- Read the articles.

- Analyze the information.

- Compare the information from the articles.

- Identify and analyze the pros and cons of microcredit.

Article 1: Microcredit was a hugely hyped solution to global poverty. What happened?

Article 2: Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps

Cyber Warfare

Cyber warfare takes place between nation-states. These are strategic attacks to deliberately cause damage to the [capacity of action] [don’t know what this means] and capability of the state to retaliate. The attacks are pre-determined and are politically motivated. This is not equivalent to a poor man’s war. Cyber warfare often includes attacks on government computers and networks as well as MNCs. Government computer and internet systems are susceptible to various types of cyberattacks like malware, phishing, botnets, and distributed denial of service, among other more sophisticated forms of cyberattack and vandalism activities.

Europol has a useful website with information regarding the types of cyber crimes: Europol: Cybercrime.

Nation-states engage in a variety of high level cybercrimes like ransomware and spyware. The types of assets that are vulnerable in this environment is not much different than with a conventional weapons attack: energy producing facilities, civilian populations, missile systems, key government systems, and some critical structures. In many cases, the success of a mission depends on an inside person, a hacker or even a spy. The attack is often as simple as logging in to a specified computer, installing a USB, and opening a file attachment. Another problem with cyberattacks is that the attack is difficult to trace, especially in a short period of time. The Darknet offers hackers and cyber warfare participants a “safe” space to congregate. Forensic work aimed at catching cyber criminals is possible, but it is time consuming. At times, hackers leave a “fingerprint” albeit it can be difficult to identify. Cyber warfare provides for speculation and uncertainty. What we know is that of the attacks are nation-state to nation-state, while others involve the use of private groups in collaboration with nation-states to operationalize the cyberattack. Such attacks are designed to penetrate and to disable the perceived enemy. Another aspect of cyber warfare is how it produces a distraction while for a country that is also preparing to attack in more conventional ways.

Examples of cyber warfare, cyber-attacks, and other cybercriminal activity are found in the Center for Strategic and International Studies website. Following are additional articles on the topic:

| Articles | Organizations |

| The Register, “Kremlin hacking crew went on a ‘Roman Holiday’ – researchers”https://www.theregister.co.uk/2018/07/16/apt28_italian_job/ | Center for Strategic and International Studies

https://www.csis.org/programs/technology-policy-program/significant-cyber-incidents |

| The Guardian, “Russia accused of series of international cyber-attackshttps://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/may/13/russia-accused-international-cyber-attacks-apt-28-sofacy-sandworm | The Rand Corporation |

| The Hill, “North Korea’s Nuclear Thread is Nothing Compared to Its Cyberwarfare” | Interpol |

| Forbes, “Cyberwarfare Will Explode In 2020 (Because It’s Cheap, Easy And Effective)” | NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence |

| Europol

https://www.europol.europa.eu/about-europol/european-cybercrime-centre-ec3 |

Cyber warfare is the new Cold War. Hackers tend to fall into three categories: 1) government sponsored; 2) independent hackers, and 3) governmental agencies. Motives are not too different from those of the Cold War: power, competition, and self-interest.

Student Activity

Study the Cold War strategies. Study the current strategies of cyber war. Then compare and contrast them. Consider the following questions: Who gains? Who loses? What are the issues at stake? How is power being used?

Climate Migrants

Climate or environmental migrants are increasing as a result of climate change. Sweden was one of the first countries to construct “a special category as a ‘person in need of protection’ who is unable to return to his native country because of an environmental disaster.”[23] Climate migrants are a newer development in international politics. The Migration, Environment and Climate Change (MECC) Division of the UN Migration Agency (IOM) prefers the term climate migrants to climate refugees. The argument made to call these individuals migrants is based on maintaining the integrity of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Another element is how the term ‘refugee’ fails to address the specific challenges faced by persons who migrate due to climate. “In 2018 alone, 17.2 million new displacements associated with disasters in 148 countries and territories were recorder (IDMC) and 764,000 people in Somalia, Afghanistan and several other countries were displaced following drought (IOM).”[24] Managing these crises require empathy alongside responsibility and sound global policies. These global policies are environmental, ecological, and climatic in nature.

Student Activity

What is the correlation between climate change related events and the increased number of climate migrants? What regions are most affected and why? What are the specific issues that motivate individuals to become climate migrants? Are these individuals refugees or migrants?

Water issues

Based on the Water Convention (adopted in 1992, in full force by 1996, and in 2016 all UN members accede), water issues are complex, require collaboration, demand transparency, promote the exchange of ideas and practices, and require good behavior. Transboundary watercourses involve the maintenance of waterway obligations, both downstream and upstream, as well as international lakes and aquifers. By no means is this an exhaustive list of issues that involve water; however, these are useful and should be considered as examples:

- Equity in water distribution

- Environmental protections and environmental assessments

- Sustainable development

- Sustainable agriculture

- Urban growth

- Human health and safety

- Pollution

- Ecology

- Alert systems

- Technological integration

- Food

- Clean, safe, and potable water

The collaborative efforts in countries from Africa, to Europe, and to Central Asia demonstrate that exchange of good practices, respect for obligations, and adoption of soft international law and protocols is not only possible, but is actionable. It is necessary to create and protect good practices to save international transboundary water systems. “Transboundary water cooperation has the potential to generate many significant benefits for cooperating countries, such as accelerated economic growth, improved well-being, enhanced environmental sustainability and increased political stability.”[25]

Transnational issues reveal how important international relations is today. The complexity of the issues and the goals of international actors allow international scholars to study events in a multilayered approach. Transnational topics offer insight on human actions and their implications in a globalized world.

Conclusion

Generally speaking, international relations scholars and students produce more questions than answers. Realism, liberalism, constructivism, radical theories, and feminism are theories that explain and analyze how the international system functions. The international community is not only difficult to define and analyze, it is also intrinsically oriented to live on with a lack of consensus. History demonstrates how resilient humans are. States work on survival of their interests and on maintaining power. Levels of analysis allow scholars various angles and explanations for understanding international events. International organizations have a history of promoting peace, mediation, and accommodation. Human struggles may be different in the 21st century as compared to previous history, but humans are no strangers to the concept of struggle and survival. Lessons from multipolar, bipolar, and unipolar international systems provide international relations scholars with models and predictability.

Further Resources

International Water Resources Association: https://www.iwra.org

https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/transboundary-waters/

Japan

https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/89apr/defend.htm

https://www.newsweek.com/japan-governor-wants-us-stop-new-marines-base-reduce-presence-1195826

https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/04/american-bases-in-japan-are-sitting-ducks/

Turkey

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/16/isis-airstrike-turkey-airspace-us-air-force

https://www.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/europe/03/20/sprj.irq.turkey.vote/index.html

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/turkey-gives-airspace-use-ok/

Notes

[1] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Translated by J. J. Graham, Chatham: Kent Wordsworth Editions, 1997 [1827], 333, 335,

[2] Correlates of War, “About the Correlates of War Project,” Correlates of War, accessed September 27, 2021, https://correlatesofwar.org/.

[3] G.E.M. de Ste. Croix, The Origins of the Peloponnesian War, Gerald Duckworth and Co. Ltd.: London, 1972, 339.

[4] G.E.M. de Ste. Croix, The Origins of the Peloponnesian War, 340.

[5] G. E. M. de St. Croix, The Origins of the Peloponnesian War, 98.

[6] NATO is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization with a focus on Atlantic security of the U.S. and its allies in Europe. It is a mutual defense organization.

[7] WARSAW Pact was created to promote the security of USSR and its allies as a response to NATO’s creation. It was a collective security organization.

[8] MERCOSUR, “Mercosur Official Website,” MERCOSUR, 2021, https://www.mercosur.int/en/.

[9] David Vivas-Eugui, “Regional and Bilateral Agreements and a TRIPS-plus World: the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA),” Geneva: Quaker United Nations Office, 2003.

[10] Carranza, “MERCOSUR, The Free Trade Area of The Americas and the Future of U.S. Hegemony in Latin America,” Fordham International Law Journal 27, n. 3 (2003), 1063-64.

[11] Realism does not mean conservatism. Liberalism does not “liberal” in our current political context. These are not domestic attributes, concepts, or theories. In international relations, they have their own identity and they are independent theories from domestic interpretation.

[12] International Monetary Fund, “International Monetary Fund – Homepage,” IMF, 2021, https://www.imf.org/en/home.

[13] The World Bank Group, “World Bank Group – International Development, Poverty, & Sustainability,” World Bank, 2021, https://www.worldbank.org/en/home.

[14] World Trade Organization, “World Trade Organization – Global Trade,” World Trade Organization – Home page – Global trade, 2021, https://www.wto.org/.

[15] INTERPOL, “The International Criminal Police Organization,” INTERPOL, 2021, https://www.interpol.int/.

[16] Mustika Larasati Hapsoro, “ASEAN Member States Adopt Regional Action Plan to Tackle Plastic Pollution,” Association of Southeast Asian Nations, May 28, 2021, https://asean.org/asean-member-states-adopt-regional-action-plan-to-tackle-plastic-pollution/.

[17] “Home,” Home | African Union (The African Union Commission), accessed September 27, 2021, https://au.int/.

[18] International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), “Official Web Site of the IAEA,” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) (International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 2021), https://www.iaea.org/.

[19] African Union Commission, and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. “Meeting of African Ministers for Agriculture; Declaration on Food Security and Nutrition during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Meeting of African Ministers for Agriculture; Declaration on Food Security and Nutrition During the COVID-19 Pandemic | African Union. The African Union Commission, April 27, 2020. https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20200427/meeting-african-ministers-agriculture-declaration-food-security-and-nutrition, 6.

[20] Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “Malaria: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/our-work/programs/global-health/malaria, Accessed 4/29/2020.

[21] Maria Laura Canineu, “Brazil Needs More Pesticide Regulation, Not Less,” Human Rights Watch, December 23, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/12/23/brazil-needs-more-pesticide-regulation-not-less#. Accessed 4/29/2020.

[22] United Nations. “United Nations Millennium Development Goals.” United Nations. United Nations. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/. Accessed 5/12/2020

[23] Oli Brown, Migration and Climate Change, (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, Migration Series n. 31, 2008), 39.

[24] Ionesco, “Let’s Talk About Climate Migrants, Not Climate Refugees” 06 June 2019, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/06/lets-talk-about-climate-migrants-not-climate-refugees/. Accessed 05/05/2020; IOM, “IOM UN Migration,” International Organization for Migration, 2021, https://www.iom.int/.; IDMC, “IDMC,” IDMC, 2021, https://www.internal-displacement.org/.

[25] UNECE, “Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes: The Water Convention: Responding to Global Water Challenges,” 2018, 9.

References

African Union Commission, and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. “Meeting of African Ministers for Agriculture; Declaration on Food Security and Nutrition during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Meeting of African Ministers for Agriculture; Declaration on Food Security and Nutrition During the COVID-19 Pandemic | African Union. The African Union Commission, April 27, 2020. https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20200427/meeting-african-ministers-agriculture-declaration-food-security-and-nutrition.

Banerjee, Abhijit, Dean Karlan and Jonathan Zinman. “Six Randomized Evaluations of Micro Credit: Introduction and Further Steps.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7, n. 1 (2015): 1-21.

Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principle of Morals and Legislation. Oxford: Oxford At the Clarendon Press 1823 (1780, 1789).

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “Malaria: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/our-work/programs/global-health/malaria.

Brown, Oli. Migration and Climate Change (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, Migration Series n. 31, 2008). Accessed 05/04/2020

Canineu, Maria Laura. “Brazil Needs More Pesticide Regulation, Not Less.” Human Rights Watch, December 23, 2019. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/12/23/brazil-needs-more-pesticide-regulation-not-less#.

Cardoso, Fernando Henrique and Enzo Faletto. Dependency and Development in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

Carr, Edward Hallett. The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 1919-1939: Introduction to the Study of International Relations. New York: Harper Perennial. 1964 (1939).

Carranza, Mario E. “MERCOSUR, The Free Trade Area of The Americas and the Future of U.S. Hegemony in Latin America.” Fordham International Law Journal 27, n. 3 (2003), 1028-1069.

Clark, Ann Marie, Elisabeth J. Friedman, and Kathryn Hochsteller. “The Sovereign Limits of Global Civil Society: A Comparison of NGO Participation in UN Work Conferences on the Environment, Human Rights, and Women.” World Politics 51, n. 1 (October, 1998), 1-35.

Clausewitz, Carl Von. On War. Translated by J. J. Graham. Chatham: Kent Wordsworth Editions, 1997 [1827].

Correlates of War. “About the Correlates of War Project.” Correlates of War. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://correlatesofwar.org/.

Croix, G. E. M. de Ste. The Origins of the Peloponnesian War. Gerald Duckworth and Co. Ltd.: London, 1972.

Curtis, Michael. The Great Political Theories, Volumes 1 and 2. New York: Avon Books, 1981.

Derian, James Der. Critical Practices in International Theory: Selected Essays. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Doyle, Michael W. Ways of War and Peace. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1997.

Enloe, Cynthia. Bananas, Beaches, and Bases. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Grote, George. A History of Greece. Volume II. New York: American Book Exchange, 1881.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Edited by Michael Oakeshott. New York: Collier Books, 1962 (1651).

Hobson, John A. Imperialism: A Study. New York: Cosimo Classics, 2005 (1902). http://oll-resources.s3.amazonaws.com/titles/278/0175_Bk.pdf Accessed 05/13/2020 Digitally formatted by Online Liberty Fund

“Home.” Home | African Union. The African Union Commission. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://au.int/.

Human Rights Watch https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/12/23/brazil-needs-more-pesticide-regulation-not-less# accessed 4/29/2020

IDMC. IDMC, 2021. https://www.internal-displacement.org/.

International Monetary Fund. “International Monetary Fund – Homepage.” IMF, 2021. https://www.imf.org/en/home.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). “Official Web Site of the IAEA.” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 2021. https://www.iaea.org/.

INTERPOL. “The International Criminal Police Organization.” INTERPOL, 2021. https://www.interpol.int/.

IOM. “IOM UN Migration.” International Organization for Migration, 2021. https://www.iom.int/.

Ionesco, Dina. “Let’s Talk About Climate Migrants, Not Climate Refugees.” 06 June 2019, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/06/lets-talk-about-climate-migrants-not-climate-refugees/ Accessed 05/05/2020

Kennan, George F. Memoirs 1925-1950. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1967.

Kissinger, Henry. American Foreign Policy: Three Essays. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1977, 3rd edition.

Larasati Hapsoro, Mustika. “ASEAN Member States Adopt Regional Action Plan to Tackle Plastic Pollution.” Association of Southeast Asian Nations, May 28, 2021. https://asean.org/asean-member-states-adopt-regional-action-plan-to-tackle-plastic-pollution/.

Lenin, V.I. Imperialism, The Highest State of Capitalism. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1997.

Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. Edited by Peter Laslett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989 (1690).

Luxemburg, Rosa. The Accumulation of Capital. Translated by Agnes Schwazschild. New Haven: Yale Press, 1951. Guttenberg Project November 19 2012, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41405/41405-h/41405-h.htm Accessed 05/13/2020.

Machiavelli, Niccolò. The Prince. Edited by and Translated by Peter Bondanella and Mark Musa. New York: Penguin Books, 1979 (1532).

Mearshemeir, John J. Conventional Deterrence. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

Mearshemeir, John J. “John Mearshemeir,” YouTube video, 7:35, July 3, 2017.

MERCOSUR, “Mercosur Official Website,” MERCOSUR, 2021, https://www.mercosur.int/en/.

Morgenthau, Hans. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992 (1948).

Nye, Jr., Joseph S. “Joseph S. Nye, Jr.: What is Power?” YouTube video, 8:23, April 19, 2016.

Nye, Jr., Joseph S. “Soft Power and the Public Diplomacy Revisited.” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 14, n. 1-2 (April 2019): 1-14.

Nye, Jr., Joseph S. “Protecting Democracy in an Era of Cyber Information War.” February 2019.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Social Contract and Discourses. Translated by G.D. H. Cole. Charles E. Tuttle: Vermont, 1993.

Russett, Bruce. Grasping The Democratic Peace: Principles for a Post-Cold War World. Princeton: New Jersey Princeton University Press, 1993.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1976.

Smith, Adam. Wealth of Nations. Edited by Kathryn Sutherland. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1993 (1776).

The World Bank Group. “World Bank Group – International Development, Poverty, & Sustainability.” World Bank, 2021. https://www.worldbank.org/en/home.

Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. [431 BC] Translated by Richard Crawley. Guttenberg Project February 7 2013 https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7142/7142-h/7142-h.htm Last accessed 05/12/2020

Tickner, J. Ann. Gender In International Relations: Feminist Perspectives, On Achieving Global Security. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992.

Tucker, Robert C., edited by. The Marx-Engels Reader. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978, 2nd edition.

UNECE, “Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes: The Water Convention: Responding to Global Water Challenges,” 2018, 9. Accessed 5/5/2020

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), “Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes: The Water Convention: Responding to Global Water Challenges,” Geneva, 2018. http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/water/publications/brochure/Brochures_Leaflets/A4_trifold_en_web_2018.pdf Accessed 5/5/2020

United Nations. “United Nations Millennium Development Goals.” United Nations. United Nations. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/. Accessed 5/12/2020.

Vivas-Eugui, David. “Regional and Bilateral Agreements and a TRIPS-plus World: the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA).” Geneva: Quaker United Nations Office, 2003.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. “The Itinerary of World-Systems Analysis; or How to Resist Becoming a Theory.” Edited by J. Berger and M. Zelditch Jr. New Directions in Contemporary Sociological Theory. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002, 358-376. https://iwallerstein.com/wp-content/uploads/docs/THEORY.pdf Accessed 05/13/2020

Walt, Stephen M. The Origins of Alliances. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1987.

Waltz, Kenneth. Man the State and War: A Theoretical Analysis. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959.

Wendt, Alex. Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

World Trade Organization. “World Trade Organization – Global Trade.” World Trade Organization – Home page – Global trade, 2021. https://www.wto.org/.