Chapter 2: Political Science

What is Political Science?

Dr. Elsa Dias and Dr. Rick Foster

Chapter 2 What is Political Science?

“The man who knows and concerns himself with his own interests is thought to have practical wisdom, while politicians are thought to be busybodies.”[1]

“Political Science must be based on a recognition of the interdependence of theory and practice, which can be attained only through a combination of utopia and reality.”[2]

Learning Objectives

Students should be able to:

- Identify what is political science

- Distinguish among the various subfields in political science

- Investigate how the major of political science contributes to educate students and prepare them for “the real world”

Political science is one of the social sciences like Sociology, Anthropology, and Psychology. Political Science studies the state, institutions, and power as well as how all these variables interconnect with culture, economics, identity, and society, in both the domestic and international spheres. It’s consistent focus on power helps separate political science from other social sciences. The discipline has its own epistemological[3] perspectives along with normative and empirical approaches. Questions remain about how well political scientists have been able to make accurate predictions about the political world in which we live.

Any discussion of what Political Science is becomes a multi-millennial enterprise. From pre-Socratic philosophers to the 21st century, there is a multiplicity of scholars to study, who made contributions to the discipline of political science throughout the ages. Aristotle is a good start to the study of political science. Aristotle defined political science as politikê epistêmê (political knowledge). While Aristotle considered political science an art, he also looked at political science as a creative science that is normative and empirical. Aristotle maintains that, “it seems that those who aim at knowing about the art of politics need experience as well.”[4]

Aristotle provides for a vision of political science that has various dimensions; which is made clear in this explanation:

The distinction which is made between the king and the statesman is as follows: When the government is personal, the ruler is a king; when, according to the rules of the political science, the citizens rule and are ruled in turn, then he is called a statesman. … We must therefore look at the elements of which the state is composed, in order that we may see in what the different kinds of rule differ from one another, and whether any scientific result can be attained about each one of them.[5]

This Aristotelian approach to political science has created a space for the historical development of the discipline. Like Aristotle, political scientists ask questions, create hypotheses, investigate events, theorize, and provide for conceptual analysis.

| Political Theory | Domestic Politics (American Politics) | Political Behavior and Research Methods | Comparative Politics | International Relations | |

| Questions | 1. What ought to be …? | 2. What can be…? | 3. What is…? | Questions 2 and 3 | All three questions |

| Ideas | Ethical | Cautious Pragmatism | Empirical | All three ideas | All three ideas |

| Explanations | Analysis (1) | Evaluation (2) | Hypothesis (3) | Two and Three | All three |

Political Theory studies classical, contemporary, normative, and critical theories. Political theory has traditionally created a safe space for western political thought at the cost of non-western traditions. Because political science is a divided discipline, meaning that most of the time political scientists isolate themselves in their field, the result is a discipline with diverse research but little communication across its subfields.[6] The following are disciplinary subfields in political science that are generally well accepted: political theory, domestic politics (e.g.: American politics, French politics, Peruvian politics, etc.), political behavior and research methods, comparative politics, and international relations.[7] Each one will be discussed in turn.

Speaking about political theory, political theorist Arlene Saxonhouse states that:

Reading texts is not merely illuminating, historically enlightening; … the careful reading of literature is the source of our humanity and identity. … there are those who turn to political theory for enlightenment about our condition in the contemporary world, for guidance about the normative choices that we as political creatures confront, … the conversations we must have about the meaning of political life.[8]

Political theorists ask challenging questions that confront the political world. The dialogue about political life is key to effective governance. In short, political theorists ask normative questions seeking to provoke discussions that explain political life through various lenses.

Domestic Politics (focused here in American politics) emphasizes state and local politics, national government, public policy, public opinion, and civic engagement. In the United States, studying American government allows for a discussion of the relationship among local, state, and federal levels of government. Civil rights and civil liberties interpret domestic relations between the state, government, and individuals.

Writing to George Wythe in 1776, John Adams makes for a series of intriguing arguments for the formation of a new American government. Adams’ “Thoughts on Government” allows the student of early American political thought to understand how American institutions would take shape and how the Constitution would allocate powers to the different branches of government. While John Adams was still a British subject and the British empire still had hold of the thirteen colonies, he emphasizes, how:

a republic is the best of governments, … that form of government which is best contrived to secure an impartial and exact execution of the laws, is the best of republics. … It should think, feel, reason and act like them. That it may be the interest of this assembly to do strict justice at all times, it should be an equal representation … Great care should be taken to effect this, and to prevent unfair, partial, and corrupt elections.[9]

The predictions contained in this document demonstrate how much debate, thought, consideration, analysis, and compromise took place to form the United States even before the revolutionary war. In 1776, Adams provides for a blueprint of the republic that is enjoyed today by most Americans.

Political Behavior and Research Methods promote scientific knowledge for the discipline. Empirical analysis includes the use of surveys and questionnaires, observations and data coding, document analysis, and quasi-experimental design research. By using methodology, political scientists have the ability to make certain types of predictions, like how voters will behave or how wars begin (see J. David Singer’s Correlates of War Project). Political behavior received its impetus from the behavioral revolution of the 1950s and 1960s.

A large part of what political scientists do in research methods is quasi-experimental design. Campbell and Stanley state that, “There are many natural social settings in which the research person can introduce something like experimental design into his scheduling of data collection procedures.”[10] The social sciences in general have a natural propensity for quasi-experimental design; because of the types of variables researchers use, the conclusion is “every experiment is imperfect.”[11]

The researcher must be aware of both the strengths and weakness of the experiment. “The task of theory-testing data collection is therefore predominantly one of rejecting inadequate hypotheses.”[12] Political scientists use the scientific method to accomplish their research (research question/purpose, research, hypothesis, testing and experiment, data collection and analysis, and conclusion). The issue remains for political scientists: how to control human subjects? Of course, how to make effective predictions about political behavior and about political decision-making continues to prove difficult.

Comparative Politics is one of the oldest fields in political science if one considers the work done with philosophical texts or even the work that Aristotle did with searching and studying constitutions throughout ancient Greece. Yet, comparative politics is considered a newer field in political science with a focus on comparing and contrasting countries (political culture, institutions, political parties, nationalism, electoral systems, ethnic conflict, etc.) and/or regions.

Comparative politics has made specific contributions to the discipline of political science. Political scientists ask the following questions: “What explained successes? What tensions and cleavages were unleashed by failure?”[13] For example, the comparative work in political parties lacks sustainable and consistent analysis. Political science literature “in the U.S. is not strong on comparative analysis … The American literature deals mainly with home-grown political parties and makes relatively few comparisons with parties in other countries.”[14] The goal is to have comparative politics to be broader in the study of political parties: “Comparative research on political parties pays great attention to parties’ positions on issues with cross-national significance.”[15] European scholars have produced comparative scholarship that “reflects the great strength of European political science in structural comparative politics.”[16] Comparative politics has developed asymmetrically.

The relationships among countries are critical to understand the complexity of global politics. International relations examines issues, like: 1) causes of events like war or famine; 2) globalization and trade under international political economy; 3) international organizations and various stakeholders; 4) leadership and decision making along with foreign policy; to name only a few.

Decision-Making and Leadership

While not a recognized subfield of political science, considerable work has been done in the areas of decision-making and leadership. Decisions are an essential component of human life. Making decisions for a nation and on behalf of a government is crucial, but not everyone makes those decisions. The literature on decision-making and leadership is vast. Qualities of a leader are vast and range from personal to professional and from moral or ethical to religious.

Leadership styles in the discipline of political science are typical of other social sciences. Machiavelli has been historically used with his ‘lion and the fox’ analogy to explain how leaders ought to behave in office. The Machiavellian proposition for a leader to avoid being loved or hated and for a leader to be feared made as much sense in the 16th century as it does in the 21st century.

In Leadership Matters: Unleashing the Power of Paradox (2012), Tom Cronin and Michael Genovese have an approach to leadership that helps political leaders of the 21st century to lead and be proactive in their role as effective leaders. To take liberties with Cronin and Genovese’s work, leaders must have:

- 1) personal characteristics to connect with the public;

- 2) political characteristics to negotiate with other government officials, and with other global leaders;

- 3) organizational characteristics to be able to comprehend how organizations and institutions work, their relationship, and their outcomes

| Cronin and Genovese[17] | Personal characteristics | Political characteristics | Organizational characteristics |

| [D]ecent, just, compassionate, and moral leaders | X | ||

| Effective leadership involves self-confidence, the audacity of hope, and sometimes even a fearless optimism

|

X | X | |

| Leaders must be representative—yet not too representative

|

X | ||

| Leaders invent and reinvent themselves

|

X | X | |

| Leadership often calls for intensity, enthusiasm, passion

|

X | ||

| Leaders need to unify their organizations or communities through effective negotiation and alliance building

|

X | ||

| Leaders are supposed to lead, not follow the polls

|

X | ||

| [W]e still want to believe leaders make a significant difference | X | X |

Make a list of ten qualities that a leader must have. From that list pick the top three most important qualities and explain why they are the most significant. Students should consider the personal, political, and organizational characteristics.

Student Activity

Below is a list of leaders for students to apply their lists to actual leaders. (Different leaders may be used, consider these as examples.) Consider if the leaders are successful or if they are failures and try to explain why.

| Past Leaders | Today’s Leaders |

| Alexander the Great or Alexander III (356-323 BC)

|

Paul Kagame (1957—Present)

|

| Elizabeth I (1533-1603)

|

Donald J. Trump (1946—Present) |

| Louis de XIV (1638-1715)

|

Pelé (1940—Present)

|

| Czarina Catherine the Great (1729-1796)

|

Xi Jinping (1953—Present) |

| Sojourner Truth (Isabella) (1797-1883)

|

Kim Kardashian (1980—Present) |

| Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948)

|

Angela Merkel (1954—Present) |

| Josef Stalin (1878-1953)

|

Greta Thunberg (2003—Present) |

| Mao Zedong (1893-1976)

|

Kim Jong-Un (1984—Present) |

| Mother Theresa (1910-1997)

|

Pope Francis (1936—Present) |

| Ernesto (Che) Guevara (1928-1967)

|

Mohammad bin Salman (1985—Present) |

| Confucius (551-479 BC)

|

Tawakkol Karman (1979—Present) |

Political Scientists

What political scientists do is multifaceted. Students ought to know that political scientists enjoy teaching, researching, managing, political campaigning, and lobbying among other activities. To list all important political scientists by subfield would fill a terabyte not to mention how many trees would be wasted if the book was printed. Below we have a list of unique and carefully selected political scientists by subfield. This list’s intent is to provide students and readers with a view of the breath of disciplinary knowledge produced by political scientists. Perhaps this will spark further interest in the study of political science.

Political Theory

Elinor Ostrom (1933-2012)—She was the recipient of the Sveriges Riksbank Prize of Economic Sciences of Alfred Nobel in 2009 for her work on challenging the theoretical framework of the tragedy of the commons. Rational choice theory was employed to explore cooperative relationships in small rural communities. Ostrom was able to prove how economic governance in the commons took place, and “how local property can be successfully managed by local commons without any regulation by central authorities or privatization.”[18] She was also interested in issues related to institutional diversity, the environment and sustainability, and economic governance. Ostrom also worked in public policy: “Throughout her career Ostrom was a consultant for various entities, including the State of California Local Government Reform Task Force (1973-74).”[19]

Jacques Derrida (1930-2004)—He was an Algerian French born philosopher. He was best known for developing deconstruction—analysis of text and meaning. For Derrida, the process of deconstruction took various phases in his academic progression. Derrida looks at death, including the death penalty, to explain how deconstruction works. Derrida states that: “To deconstruct death, then, that is the subject, while recalling that we do not know what it is, if and when it happens, and to whom. … What comes afterward? and so forth. But to deconstruct death. Final period. And with the same blow, to come to blows with death and put it out of action. No less than that. Death to death.”[20] Derrida suggests that while the subject of analysis is death, the reader might not know what it is. The reality is that one assumes to know, unless one breaks down the death process, it is life that we are focusing on. “This shows us that perhaps even more that justice deconstruction values … life more than anything else. But this life is not unscathed; it is life in its irreducible connection to death. Thus, what deconstruction values is survival.”[21]

Domestic Politics

Robert Dahl (1915-2014) argues that in the United States democracy was defined by the power of pluralism. He takes a macro approach to distribution of power in the United States; because of group competition, power is dispersed avoiding control by a specific group. Dahl opened the doors to the behavioral revolution. The need to quantify politics was part of Dahl’s project, in particular to quantify democratic processes. “He pioneered in rendering the American discipline of political science more scientific.”[22] On the normative side, he accepted Greek democracy with skepticism. On the American side, “Dahl never did like the Constitution. For him it had too many undemocratic intricacies such as the Electoral College and the Wyoming-equals-California aspect of the Senate.”[23] In this regard, Dahl demonstrates that democracy is less about institutional equality, and more about democratic practices and political outcomes.

Michael Genovese

Michael Genovese (1950-Present) is a presidential scholar, and political commentator. He is also an advisor and consultant for a number of bureaucracies in the United States government. Genovese’s research on the presidency has made him well known in leadership studies as well. He is the author of numerous academic articles and books.

Research Methods

To unpack and to simplify what academics do with research methods is to say that they experiment in an attempt to explain social behavior. Ultimately, what political scientists do is to identify concepts in order to create theories. “Theory building is accomplished through the testing of hypotheses derived from theory. In simple form, a theory implies (a set of) relationships among concepts. These concepts are then operationalized. Finally, models are developed to examine how the measures are related.”[24]

The behavioral revolution resulted in important contributions to the field of political science. Academics like David Easton, David Singer, Peregrine Schwartz-Shea, Chris Achen, and Dvora Yanow have made significant contributions in research methods in political science. Research methods have revolutionized the discipline.

Since the 1950s, a number of research institutes have emerged around the United States:

- Institute for Social Research https://isr.umich.edu

- Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences https://lsa.umich.edu/qmss

- ICPSR https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/

The opportunity for students to experience the results of research methods analysis is available in:

- YouGov https://today.yougov.com

- Roper Center for Public Opinion Research https://ropercenter.cornell.edu

- The Correlates of War Project https://correlatesofwar.org/history and https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/series/232

Students ought to consider the above material as informational. With this information, students are able examine how research methods produces knowledge for the discipline of political science.

Comparative Politics

Juan Linz

Juan Linz (1926-2013) studies democratic and authoritarian regimes. His important contributions to the field of political science are: 1) the “development and analysis of distinct regime types found in the world, namely totalitarian, authoritarian, sultanistic and democratic types;” 2) the design of “innovative public opinion surveys” that allowed for citizens to identify “complementary identities;” and 3) surveys which allowed for innovative studies on “nationalism in such diverse areas as Spain, Scotland, Sri Lanka and India.”[25] Linz’s books went through multiple editions, some with 30 editions or more, like The Failure of Presidential Democracy (1994) or Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes (1995). In Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes, Linz proposes a cohesive definition of totalitarian regimes:

The dimensions that we have to retain as necessary to characterize a system as totalitarian are an ideology, a single mass party and other mobilizational organizations, and concentrated power in an individual and his collaborators or a small group that is not accountable to any large constituency and cannot be dislodged from power by institutionalized, peaceful means.[26]

This definition of totalitarian regimes has been useful to many comparativist scholars since Linz developed it in 1970s. In the realm of comparative politics, his typology of regimes, like totalitarian regimes, is a centerpiece for a better understanding of governance.

International Relations

E.H. Carr

Edward Hallett Carr, a.k.a, E. H. Carr (1892-1982), is a well-known international relations theorist, diplomat, and scholar. After his diplomatic career came to a quick end, he started teaching. He was a strong supporter of peace and cautious relations with the then USSR “peace at any price must be the foundation of British policy.”[27] Carr is best known for his work The Twenty Years Crisis (1939) and for his expertise in Russian and Soviet history and politics. In 1939, his book received critiques regarding his analysis of the politics of appeasement. His analysis of realism, idealism, and power continues to be used in courses of International Relations today. Carr writes, “While politics cannot be satisfactorily defined exclusively in terms of power, it is safe to say that power is always an essential element of politics. … A political issue arising between Great Britain and Japan is something quite different from what may be formally the same issue between Great Britain and Nicaragua.”[28] Here Carr demonstrates how power works in the international system. This is how balance of power works in international relations. Countries are not perceived to have the same power, and because they have different power it affects country-to-country relations in the international system. Carr suggests that “The nation became, more than ever before, the supreme unit round which centre human demands for equality and human ambitions for predominance. … The inequality which threatened a world upheaval was not inequality between individuals, not inequality between classes, but inequality between nations.”[29] Nation-states are not equal, because they have different resources and capacity to act. During the interwar period (between World War I and World War II), the emergence of nation-states took a preeminent place in international relations. What Carr wrote in 1939 continues to be an integral part of international relations courses today; i.e., nation-states are intrinsically unequal.

Civil-military Relations

A growing area of interest in political science is civil-military relations. In a post September 11th, 2001 world, most students have faced a world where the military has become institutionalized. It is as if the military is a fourth branch of government. There are ongoing hotspots of conflict in nearly every continent. The issue of civilian-military (Civ-Mil) relations deserves some attention. The subject of the military needs to be better integrated into the discipline of political science. Because the military is ubiquitous, it is here treated independently from a specific subfield.

Some of issues like legitimacy, authority, leadership, trust, and political attitudes are variables that produce useful knowledge about Civ-Mil relations. For instance, what does public opinion say about the military? The Gallup poll has a longitudinal poll taken between 1973 and 2020 that measures public confidence in institutions. In 2020 one of the questions was, “Now I am going to read a list of institutions in American society. Please tell me how much confidence you, yourself have in each one—great deal, quite a lot, some or very little?” Some interesting results from the poll:

| 2020[30]

N=1226[31] |

Military | Presidency | Congress | Supreme Court | Banks | Police |

| “Great deal” | 40% | 22% | 6% | 18% | 17% | 23% |

| “Quite a lot” | 32% | 17% | 7% | 22% | 21% | 25% |

| Totals | 72% | 39% | 13% | 40% | 38% | 48% |

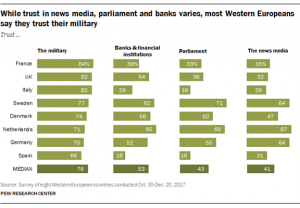

In 2017, a comparative poll of Western Europeans measuring trust in the military, demonstrates a similar trend to the United States. Public opinion reveals confidence in the military as well as trust in it. A Pew Research Center poll, in 2017, shows that the military is ahead of other institutions.[32]

While trust and confidence are not the same, it is nevertheless interesting to see that trust in the military in France is 84%, UK is 82%, and Italy is 82%. These high numbers compare with confidence in the United States in the military at 73%. However, it is important to note that there is a statistically significant point difference of 11 to 9 points in the case of the U.S. Civilian populations appear to support the military. Based on the data, one can argue that as long as the military is a semi-independent branch of government, with civilian checks, public opinion will continue to support the military.

What is Political Science to students?

Student Activity

What is political science for students? What shall students do with their degree in political science? Why is political science important? What are your academic goals?

Students are more pragmatic than their professors. In an ideal world, professors of political science would like their students to be the next generation of political scientists. However, reality hits every political science department on every campus; students want to pursue their own dreams and careers. For the most part, students do not follow the academic pursuits of their professors.

Marineau proposes three models for political science departments to offer to students: 1) Researcher; 2) Activist; and 3) Leader.[33] “Only about 5.5% of political science graduates go on to pursue doctorates in political science.”[34] The percentages make for a good case that the researcher model proposed by Marineau might not be the most interesting for students to attain. This model proposes that students learn “how to write high-quality research papers. To that end, methods training, and particularly quantitative methods, are additional important tasks.”[35] This model prepares students to attend graduate school. The next model is the activist model.

The activist model is problematic because “students are increasingly concerned with using their college education to attain financial stability rather than to affect political change.”[36] This does not mean that students are not civically minded or that they are not concerned with global and national issues, but rather that the current economy is shaping students’ academic and professional choices. The most likely model is the leader model proposed by Marineau, because it provides for “career preparation,” promotes “ethics,” develops skills like “conflict resolution, diplomacy, and negotiation,” and “include[s] mandatory internships and discipline specific service learning opportunities.”[37] Based on Marineau’s study, the leader model provides students with the skills needed for today’s job markets.

Student Activity

Which of these models: researcher, activist, and leader, do you identify with? What else do you see yourself doing? Explain. What professionally do you see yourself doing?

Conclusion

Political science is a discipline with an ancient history, with a jambalaya of subfields that do not always communicate with each other. Political theory promotes a variety of theoretical frameworks from normative to critical theory. International relations studies the relationships between nation-states. Comparative politics helps identify similarities and dissimilarities between countries and/or regions by using the comparative method on a variety of concepts like regimes, governance, etc. Research methods provides for skills in qualitative and quantitative analysis that are necessary not only in academia, but also in the job-market. Domestic politics offers deep insight into a country’s political system, governance, and social movements.

Given the global participation of militaries, it is important for students to understand that this ‘new branch of government’ is making politics and it is affecting everyone’s life. Understanding the position of the military in political affairs is becoming a necessity for civilians in general, and political scientists in particular.

Students should understand what a degree in political science can do for them. They should also be able to evaluate political science programs to see if they will provide them with the skills students need for the professions they desire to pursue.

Notes

[1] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, VI. 8, W.D. Ross, trans. The Internet Classics Archive. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.10.x.html Last accessed 09/25/2020.

[2] E. H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919-1939, New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1964, 13.

[3] A brief definition of the term epistemological: It is the theory of knowledge, in particular it is difference between fact and opinion.

[4] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, X, 9.

[5] Aristotle, Politics, I. 1, Benjamin Jowett, trans., The Internet Classics Archive, http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/politics.1.one.html Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[6] Gabriel Almond, A Discipline Divided: Schools and Sects in Political Science, Newbury Park: Sage, 1990.

[7] Michael G Rosking, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/political-science Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[8] Arlene W. Saxonhouse, “Texts and Canons: The Status of the “Great Books” in Political Theory,” in Finifter, ed. Political Science: The State of the Discipline II, Washington, D.C.: American Political Science Association, 1993, 5-6.

[9] John Adams, “Thoughts on Government,” in Frohnen, ed. The American Republic Primary Sources, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000, 197.

[10] Donald t.Campbell and Julian C.Stanley, Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research, New York: Cengage Learning, 1963, 34.

[11] Campbell and Stanley, 34.

[12] Campbell and Stanley, 35. Original emphasis.

[13]Ronald Rogowski, “Comparative Politics,” in Ada W. Finifter, ed. Political Science: The State of the Discipline II. Washington, D.C.: American Political Science Association, 1993, 432.

[14] Kenneth Janda, “Comparative Political Parties: Research and Theory,” Chapter 7, in Ada W. Finifter, ed. Political Science: The State of the Discipline II. Washington, D.C.: American Political Science Association, 1993, 163.

[15] Janda, 168. .

[16] Janda, 163.

[17] The table information directly derives from: Thomas E. Cronin, and Michael A. Genovese. Leadership Matters: Unleashing the Power of Paradox. (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2012.); and from Integral Leadership Review http://integralleadershipreview.com/7662-thomas-e-cronin-and-michael-a-genovese-leadership-matters-unleashing-the-power-of-paradox/ Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[18] Elinor Ostrom, The Library of Economics and Liberty, https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Ostrom.html Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[19] Jeanette L. Nolen, ., ed. “Elinor Ostrom.” Encyclopedia Britannica. August 3rd, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Elinor-Ostrom Last accessed 09/25/2020.

[20] Jacques Derrida, The Death Penalty (Volume 1), in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/derrida/, 240–241, Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[21] Derrida.

[22] David Mayhew, “A Biographical Memoir,” Robert Alan Dahl, 1915-2014.” National Academy of Sciences. 2018, http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/dahl-robert.pdf Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[23] Mayhew.

[24] Hank C. Jenkins-Smith, et al., Quantitative Research Methods for Political Science, 10.

[25] Joshua Tucker, “Noted Political Scientist, Sociologist Juan Linz Has Died,” The Washington Post (WP Company, October 3, 2013), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2013/10/03/noted-political-scientist-and-sociologist-juan-linz-has-died/, Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[26] Juan Linz, Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes, Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2000 [1975], 67.

[27] John Simkim, “E.H. Carr,” Spartacus Educational (Spartacus Educational, January 2020), https://spartacus-educational.com/JcarrEH.htm, Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[28] Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919-1939, 102.

[29] Carr, 227.

[30] Jeff Jones and Lydia Saad, “Gallup News Services: June Wave 1,” Gallup Poll, June 8—July 24 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/1597/confidence-institutions.aspx Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[31] Megan Brenan, “Amid Pandemic, Confidence in Key U.S. Institutions Surges,” Gallup Poll, August 12th, 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/317135/amid-pandemic-confidence-key-institutions-surges.aspx; Jeff Jones and Lydia Saad, “Gallup News Services: June Wave 1,” Gallup Poll, June 8—July 24 2020, https://news.gallup.com/poll/1597/confidence-institutions.aspx Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

[32] Courtney Johnson, “Trust in the Military Exceeds Trust in other Institutions in Western Europe and U.S.,” Pew Research Center, September 4th, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/04/trust-in-the-military-exceeds-trust-in-other-institutions-in-western-europe-and-u-s/ Last accessed 09/25/2020.

[33] Josiah Franklin Marineau. “What is the Point of a Political Science Degree?” Journal of Political Science Education, 16, n. 1 (2020): 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2019.1612756

[34] Marineau, 101.

[35] Marineau, 102.

[36] Marineau, 103.

[37] Marineau, 104.

References

Adams, John. “Thoughts on Government,” in Bruce Frohnen, ed. The American Republic: Primary Sources. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000. 196-200.

Almond, Gabriel. A Discipline Divided: Schools and Sects in Political Science. Newbury Park: Sage, 1990.

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics, VI. 8. W. D. Ross, trans. The Internet Classics Archive. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.10.x.html Last accessed 09/25/2020.

Aristotle. Politics, I. 1. Benjamin Jowett, trans. The Internet Classics Archive.

Brenan, Megan. “Amid Pandemic, Confidence in Key U.S. Institutions Surges.” Gallup Poll. August 12th, 2020. https://news.gallup.com/poll/317135/amid-pandemic-confidence-key-institutions-surges.aspx Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

Campbell, Donald T., and Julian C. Stanley. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. New York: Cengage Learning, 1963.

Carr, E. H. The Twenty Years’ Crisis 1919-1939. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1964.

Cronin, Thomas E., and Michael A. Genovese. Integral Leadership Review http://integralleadershipreview.com/7662-thomas-e-cronin-and-michael-a-genovese-leadership-matters-unleashing-the-power-of-paradox/ Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

Cronin, Thomas E., and Michael A. Genovese. Leadership Matters: Unleashing the Power of Paradox. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2012.

Derrida, Jacques. The Death Penalty (volume 1), 240–241 in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/derrida/ Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

Finifter, Ada W., ed. Political Science: The State of the Discipline II. Washington D.C.: American Political Science Association, 1993.

Frohnen, Bruce, ed. The American Republic: Primary Sources. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2002. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/politics.1.one.html Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

Integral Leadership Review, Thomas E. Cronin and Michael Genovese, October 2012. http://integralleadershipreview.com/7662-thomas-e-cronin-and-michael-a-genovese-leadership-matters-unleashing-the-power-of-paradox/ Last accessed on 09/25/2020

Janda, Kenneth. “Comparative Political Parties: Research and Theory,” Chapter 7, in Ada W. Finifter, ed. Political Science: The State of the Discipline II. Washington, D.C.: American Political Science Association, 1993, 163-191.

Jenkins-Smith, Hank C., Joseph T. Ripeberger, Gary Copeland, Matthew C. Nowlin, Tyler Hughes, Aaron L. Fister, and Wesley Wehde. Quantitative Research Methods for Political Science, Public Policy and Public Administration: With Applications in R. Creative Commons Attribution. September 12, 2017.

Johnson, Courtney. “Trust in the Military Exceeds Trust in other Institutions in Western Europe and U.S.” Pew Research Center. September 4th, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/04/trust-in-the-military-exceeds-trust-in-other-institutions-in-western-europe-and-u-s/ Last accessed 09/25/2020.

Jones, Jeff, and Lydia Saad. “Gallup News Services: June Wave 1.” Gallup Poll. June 8—July 24 2020. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1597/confidence-institutions.aspx Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

Linz, Juan J. Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2000 [1975].

Marineau, Josiah Franklin. “What is the Point of a Political Science Degree?” Journal of Political Science Education 16, n. 1 (2020): 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2019.1612756

Mayhew, David. “A Biographical Memoir: Robert Alan Dahl, 1915-2014.” National Academy of Sciences. 2018. http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/dahl-robert.pdf Last accessed on 09/25/2020

Nolen, Jeannette L., ed. “Elinor Ostrom.” Encyclopedia Britannica. August 3rd, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Elinor-Ostrom Last accessed on 09/25/2020

Ostrom, Elinor. The Library of Economics and Liberty. https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Ostrom.html Last accessed on 09/25/2020

Rogowski, Ronald. “Comparative Politics,” in Ada W. Finifter, ed. Political Science: The State of the Discipline II. Washington, D.C.: American Political Science Association, 1993, 431-449.

Rosking, Michael G. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/political-science Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

Saxonhouse, Arlene W. “Texts and Canons: The Status of the “Great Books” in Political Theory,” in Ada Finifter, ed. Political Science: The State of the Discipline II. Washington, D.C.: American Political Science Association, 1993, 3-26.

Simkim, John. “E.H. Carr.” Spartacus Educational. Spartacus Educational, January 2020. https://spartacus-educational.com/JcarrEH.htm. Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

Tucker, Joshua. “Noted Political Scientist, Sociologies Juan Linz Has Died.” Washington Post. October 3rd, 2013. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2013/10/03/noted-political-scientist-and-sociologist-juan-linz-has-died/ Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

Figures – References

Johnson, Courtney. “Trust in the Military Exceeds Trust in other Institutions in Western Europe and U.S.” Pew Research Center. September 4th, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/04/trust-in-the-military-exceeds-trust-in-other-institutions-in-western-europe-and-u-s/ Last accessed 09/25/2020.

Gleason, David B. File: The Pentagon January 2008. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, January 12, 2008. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Pentagon_January_2008.jpg.

File: Aristotle Altemps Inv8575. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, November 11, 2006. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aristotle_Altemps_Inv8575.jpg.

File: Derrida-by-Pablo-Secca. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, August 6, 2009. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Derrida-by-Pablo-Secca.jpg.

File: Robert A. Dahl in the Classroom. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, September 7, 2014. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Robert_A._Dahl_in_the_Classroom.jpg.

IMCBerea College. File: Berea College 20111031 Campus Students-63L (20715117166). Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, April 24, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berea_College_20111031_Campus_students-63L_(20715117166).jpg.

Indiana University. File: Elinor Ostrom – Journal.pbio.1001405.g001. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, October 25, 2012. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elinor_Ostrom_-_journal.pbio.1001405.g001.png.