Chapter 1: Politics

What is Politics?

Dr. Elsa Dias and Dr. Rick Foster

Chapter 1: What is Politics?

“People are fickle by nature; and it is simple to convince them of something but difficult to hold them in that conviction; and, therefore, affairs should be managed in such a way that when they no longer believe, they can be made to believe by force.”[1]

Learning Objectives

Students should be able to:

- Understand what politics is

- Understand the nature of competing interests in politics

- Identify how politics intersects various aspects of an individual’s life

Introduction

Politics is treated in this chapter as different from political science. The world of politics is complicated. Human interaction has implications for what counts as political. Politics is a contested space where the art of compromise is exercised to achieve an objective. This is a simple definition of politics. It is designed to set up a conversation based on a common thread of what politics is. However, the chapter will continue to broaden the definition as well as provide for contextualization.

Individuals are skeptical about politics. In general, most individuals do not like politics. Why is it that most people do not like politics? Why is politics important? What do we gain by having a better understanding of what politics is? Why does skepticism surround politics? Why do individuals associate politics with government and not their personal life? Why is politics a contested space?

Before reading the chapter think about politics. Write down the first three words that come to mind that describe what is politics.

What is politics?

Or click here to watch the video!

How do your three words compare with those provided by English respondents to the same question?

A Theoretical Perspective: In Search of a definition

Political theorists have worked on defining politics for millennia. Yet some theorists have directed their efforts into the discipline of political science not necessarily into pragmatic ‘real life’ politics. But there are glimpses of how to understand and define politics by the theorists. This chapter focuses on politics, not political science (chapter 2). Politics is treated as a high-level interaction among decision makers. In this section, politics is being viewed through the lens of historical figures, in this case political theorists to be precise. Keep in mind that politics is a factor of their reality, both of their theorizing and of their experiences. The following are important historical characters that have theorized various concepts like equality, leadership, and participation that intersect with politics. Machiavelli, Rousseau, Lasswell, Arendt, and de Gouges have made important contributions to politics.

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) put moralistic politics aside and pursued a politics based on power and protection of the state. For some theorists, Machiavelli is a realist. For Machiavelli, the sheer exercise of power is not the solution. Virtú is required to exercise power to maintain the state. Virtú, in the prince, is a process to acquire and exercise skills of leadership like “how to use the masks of the fox and the lion, whose natures, as I say above, a prince must imitate.”[2] The prince, or the leader, must have virtú as a personal characteristic, because the prince’s need for power is not personal but is used to maintain (even protect) the state. Machiavelli argues that: “a wise prince should think of a method by which his citizens, at all times and in every circumstance, will need the assistance of the state and of himself.”[3] Machiavelli offers a pragmatic theory of power and the state. Machiavelli lived in an era of tense politics and conspiracies; therefore, his goal as a diplomat was to secure Italian borders and create a strong government. In this case, politics is governing and given the power struggle, politics was certainly contested. The formal unification of Italy was Machiavelli’s goal, a necessary step for Italy so that the principalities would not fall prey to foreign interference and to the whims of princes.[4] In this context, Machiavelli is pragmatic both as a diplomat and as a philosopher. Italy did not unify for another 400 years, however. It was a long process with a number of conflicts for independence that ended in 1871 with the full unification of Italy.

Why is it important for citizens to be dependent on the state? How did the situation in the principalities of Italy influence Machiavelli’s ideas? Why did Machiavelli pick the lion and the fox as qualities for the prince?

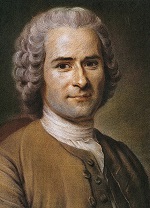

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) describes political affairs as follows: “If our politicians were less blinded by their ambition, they would see how impossible it is or any establishment whatever to act in the spirit of its institution, unless it is guided in accordance with the law of duty.”[5] This description of politics is as equally applicable today. Perhaps politics is not a new phenomenon, because politicians continue to aggrandize their power. Rousseau identified a process to manage politics, and it is about a compromise between the individual’s will and a legitimate source of authority. Politics is the compromise of all individuals’ wills to form the general will (a concept unique to Rousseau) to create a legitimate government “of the sum of the differences.”[6] In regards to the general will, Rousseau states that: “It is therefore essential, if the general will is to be able to make itself known, that there should be no partial society in the state and that each citizen should express only his own opinion … the general will shall always be enlightened, and that the people shall in no way deceive itself.”[7] Rousseau finds that in order to participate in political life it is essential that one is honest with one’s opinion. The compromise of the differences of opinion form the general will. Today, this could result in avoiding politization of ideas in order to create effective politics via compromise.

How does the Rousseau’s general will compare to today’s public opinion? How can an individual identify the general will in political life? Provide examples of compromises in politics.

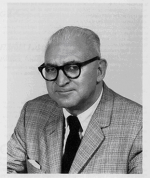

Harold Lasswell (1902-1978) authored the book Politics: Who Gets What, When, and How (1936). Lasswell is a well-known political scientist who theorized about resource distribution and provided for a historically important definition of what politics is. The idea is to have a political community where the political system decides on the allocation of resources. Governance includes the process of resource allocation. Politics as suggested by Lasswell is the pragmatic distribution of resources and the controversial decision-making process of who gets what. Lasswell introduces political economy to the conversation of what is politics. In Lasswell’s argument politics is contested, because it does not account for equal or equitable distribution of resources. The government allocates resources when it deems necessary not at the whim of individuals.

Are Lasswell’s ideas applicable to politics today? How accurate are his ideas? What lessons can individuals draw from Lasswell?

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) makes one raise the following question: What is the nature of politics and political life? If politics involves action, for Arendt, action is a public category. Politics is part of our experiences and interactions with others. As Arendt puts it:

Action, the only activity that goes on directly between men…corresponds to the human condition of plurality, to the fact that men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world. While all aspects of the human condition are somehow related to politics, this plurality is specifically the condition – not only the conditio sine qua non, but the conditio per quam – of all political life.[8]

Arendt proceeds to theorize that such political action necessitates a public space, like the Athenian polis where political discourses were an ongoing activity of citizens. It is in this space that politics takes place with all the contestations brought forth by those able to participate in this political space. Individuals participating in political action through conversation and speech create a political community—such action is politics.

Arendt suggests that human actions are related to politics. Do individuals today think that one’s actions are political? Are students’ actions on campus political when they speak against tuition hikes? Based on Arendt’s argument can non-citizens participate in political action? Is Arendt’s theory too exclusionary?

Failure to understand the historical nature of politics and the struggle to find a definition is important for the study of politics today. What politics is all about, what counts as politics, what is legitimate politics, and what is a reasonable public concern are issues contested by feminist theorists. Feminist critiques insert the possibility of what is a legitimate space and speech for public concern. Politics is therefore more inclusive. Politics is about contesting speech and space about what counts as a legitimate public concern. A critical question must be asked: while politics is a well-accepted aspect of public life, what happens to the private life of individuals? Are women’s lives political?

Feminist Critique

In order to contextualize feminist theoretical approach of what is politics, Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793) is useful, because her feminist critique of politics starts with how the public/private divide is problematic as well as the associations fostered in each sphere. Olympe de Gouges’ critique of the French Revolution led her to write the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and Citizen (1791). The title identifies the public/private divide and the politics therein contained are discussed in the text:

The mothers, daughters, and sisters, representatives of the nation, demand to be constituted a national assembly … Consequently, the sex that is superior in beauty as well as in courage of maternal suffering, recognizes and declares, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following rights of woman and citizen. … The goal of every political association is the preservation of the natural and irrevocable rights of Woman and Man. … Guarantee of the rights of woman and female citizens requires the existence of public services. … Do not fear that our French legislators, who are correcting this morality, which was for such a long time appended to the realm of politics but is no longer fashionable, will again say to you, “Women, what do we have in common with you?” You must answer, “Everything!”[9]

The importance of de Gouges for the discussion of what is politics is how she bridges the public/private divide. She includes women as private: ‘mothers, daughters, and sisters’ ‘courage of maternal suffering;’ as public: ‘woman and citizen;’ and finally, as equal to man: ‘irrevocable rights of Woman and Man.’ The multilayered argument proposed by de Gouges obligates the reader to recognize that women are active in both the private and the public sphere, that women challenged what politics is even in 1790s France, and that women participated and demanded that their actions and their speech be political. Arendt’s human action is feminized by de Gouges.

Definitions and critiques have limited practicality for everyday political dialogue, however; for political scientists, they are essential to understand that politics derives from epistemological, normative, and scientific perspectives. The complexities of politics are intriguing to political scientists. Yet politics must be understood by everyone, because it has implications for everyday life. Much like what de Gouges suggested during her era, today what women do, what they say, what counts as political and legitimate, falls under politics. The private is political. To move beyond the private realm, one identifies political issues in everyday life. It is important to recognize that everyday life produces politics. This is particularly true in times of natural disasters.

Complexities of Politicization

While everyday life is political, as it has been suggested, politicizing it takes a negative twist on politics. Politicizing events like hurricanes has direct consequences on the lives of individuals. In times of distress, like in a hurricane, the mundane lives of individuals became national news, and thus political. One must question what are the consequences of ‘making it’ on national news? Does this create a space for political empathy? Does this mean that human suffering is now being used as a space of contestation for others to gain political power? In order to be an effective contested space, politics must adapt to the circumstances of everyday life.

Politicizing is to bring attention to issues while using values and ideology to distort the true meaning of events or issues. The idea is to politicize everyday events, or even, extraordinary events for political gain. Politicizing issues like hurricanes and tragedies leads to a divisive national dialogue with partisan overtones. Politicizing issues is a means of controlling the public dialogue and message. For example, by politicizing drinkable water, the public loses the opportunity to create meaningful change. Drinkable water should be a human right, and it should not be used to express political ideological views. Politicizing does not necessarily mean that change of status quo will occur. However, to make politics means to put the issue in the hearts and minds of individuals so that the issue becomes political, contested, and ready for change. The headlines make a difference on how individuals process the information. Politicizing the condition of Puerto Ricans after Hurricane Maria in 2017 provided for attention to the situation on the ground, which rallied Congress to release more funding for the island’s recovery. However, did the conditions associated with this congressional aid make an impact on the everyday life of Puerto Ricans? Coronavirus made it to President Trump’s State of the Union address in 2020, but will it translate into action that promotes the well-being and the safety of Americans?[10] In this event, President Trump was making politics; however, when President Trump called the coronavirus “a hoax” he was politicizing it.[11] A simple question remains, what are the political consequences of politicizing issues for the everyday life of individuals? What are the effects of politicizing issues on the ability of the government to make decisions and to create effective public policy?

Politics and Government Decisions

Government provides for security. For some individuals, this means that government maintains legitimacy by promoting the rule of law and by the electoral process. Governments must create conditions for the people to achieve their goals. This is achieved by politics of compromise. This approach to politics allows for people to participate in politics by having “skin in the game.” This means that this government is also “your” government. Therefore, those invested in politics perceive the government as legitimate and responsive to their needs. The democratic process of governing opens a space for individuals to contest government action. Another approach that government uses is the “carrot and stick” approach which promotes politics of satisfaction. This means that when the government provides for goods and services, the recipients must meet criteria and perform mandatory requirements in exchange. In the United States, participation in welfare programs have mandated criteria, and its recipients must not only meet the criteria, but also do the required activities in order to maintain their benefits. How the “carrot and stick” are defined and implemented is by politics. It is the process of negotiating; which eventually evolves into public policy.

Public and Private Politics

Student Activity: What is political about…

Make a list of 10 daily activities you do. Then think about how much government is involved in each one of those activities. Then try to identify what level of government is involved (local, state, national, and/or international). Finally, identify if these activities are politics or political science.

The suggestion to include mundane daily activities as political is contested. In part because, proponents of narrow definitions and concepts of politics think that such broadening of ‘the political’ takes away the meaning of politics and devalues politics. By processing daily activities and critically thinking about what individuals do, one can identify the role of government as well as how political decisions affect personal spaces. It is imperative to have a voice in transforming the individual into a political being. What gets to count as legitimate politics and whose voices are heard plays a role in (re)shaping the public/private divide. History has taught that the dichotomy of public/private divide is not sustainable. From the ancient Agora to the protests of 2020, what counts as political has implications for the well-being of individuals.

- Figure 3.3 Marble bust of Cicero

- Figure 7.2 Marble carving of Aristotle’s head

The Aristotelian divide of oikos (private realm of the household) and polis (the public realm, political community, and political activity) provides for a nice start to the conversation of space in relation to where politics is taking place.

The Aristotelian model continues to be a point of reference for political science students. Nevertheless, this dichotomy of public/private divide is systematically challenged. Generally, what is accepted as public is the traditional Athenian polis. The participants were Athenian citizens, or white men with property, an elite section of men who participated in public life. The Athenian polis left out women, servants, slaves, most merchants and traders. This model changed little in history. An important element of public politics is not only who counts, but what counts as legitimate politics. Public politics takes place in public spaces, and therefore, counts as legitimate politics. What happens when one complicates public politics by adding different actors and different issues that have been historically relegated to the private sphere?

The private sphere is important, because of the types of politics and economic relations it affects. Social relations are best described by a system of patriarchy that displaced women. Racial relations are also key to this dichotomy. What happens to black and brown bodies matters for a healthy political life. Legitimate political life must address the disparities in racial politics that disproportionately affect black, brown, and immigrant neighborhoods. These spaces while public were considered semi-private—these are marginalized communities. The death of Mr. George Floyd in 2020 made clear how politics has marginalized these communities. Race and gender offer voices that have been historically marginalized. In politics, this public/private divide has silenced women’s political participation and displaced their voices. Historically, the state has created laws that have discriminated against women. The various feminist movements have bridged the public/private divide. Today’s public sphere has been enriched, because what women do in the private sphere not only has been expanded but has implications for the public sphere. These spheres are subject to political, social, and economic contestations. For example, the unpaid labor that women perform in the home, like childrearing or caring for elderly parents, reduces women’s ability to participate in public sphere, in the economic system, and in political affairs. The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) estimated that 60 percent of caregivers are women. The impact of this unpaid work is that women will receive less in social security and in employer contributions. Because women live longer than men on average, having a smaller pension has long-term implications for their well-being and ability to participate in the public sphere in their older age.[12]

State discrimination against people of color has deep historical roots. Social and economic discrimination are continued realities in communities of color as well as in immigrant communities.

Intersectionality theory helps to assert the necessity to move beyond the public/private divide. Individuals have various identities that help them construct perceptions about politics. To articulate an inclusive politics, one must recognize the various identities one individual possesses. A college student may be homeless, white, a parent, and female. A police officer may identify as transgender, Latino, middle class, and living in the suburbs with children. These individuals have different needs, wants, and put different demands on government.

Listen to the Ted Talk by Kimberle Crenshaw who explains intersectionality:

Or click here to watch the TED Talk by Kimberle Crenshaw

Last accessed on 9/25/2020

An interesting view of intersectionality from a non-academic perspective:

Blog: What is intersectionality, and what does it have to do with me?

Last accessed on 09/25/2020

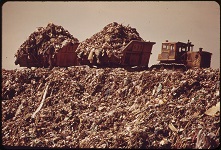

Intersectionality theory broadens one’s view of politics and the ‘real world’ by adding identity to the mix. It also sheds light on sensitive issues that affect individuals, and therefore, their community disproportionately. An interesting, and possibly surprising way to use intersectionality is to apply it to some service, such as garbage collection. How can intersectionality theory be used in studying garbage? Garbage pick-up produces awareness to who receives the service and who is collecting rubbish. Who produces rubbish? Is garbage pick-up an essential job? What is the impact of garbage collection on the economy? Where does the garbage go?

Imagine not having garbage pick-up in a city with 1 million people. While in the United States garbage pick-up is a private, commercial activity, in other countries it is the state that collects garbage. In either case, if all of a sudden garbage started to accumulate in one’s house, then in the neighborhood, and finally, in the city what would an individual do? How would one person solve the situation? Who would be held accountable? Are garbage collectors respected in the community? Are they paid well? Do beneficiaries of this service appreciate the service as well as the workers? While most garbage is produced in private, the implications for the lack of this service have public consequences. Garbage accumulation has enormous implications for public health, for the environment, and for the economy.

Student Activity

Please read the article and learn how complex the politics of garbage can be. Read the article and take notes. Reflect on the issues studied thus far in the chapter.

Article: Trash Fight: The long voyage of New York’s unwanted garbage barge By Dick Sheridan

Last accessed on 09/25/2020

What are the lessons from the article? What are the implications for public life? What can an individual do to minimize such a difficult situation? From this article, identify, at least the following:

- city politics

- state politics

- federal politics

- interstate politics

- individual politics

Intersectionality and everyday politics have increased the understanding of politics as a contested space. These new approaches have created a more inclusive politics. The following scenarios are designed to analyze action politics. The actions and decisions individuals make have consequences.

Student Activity

Examine the scenarios below:

| Issue | Private | Public | Student comments | Intersectionality issues |

| 1. Clean water in the household | ||||

| 2. Child marriage (family tradition, customs) | ||||

| 3. Crop subsidies

|

||||

| 4. Whale hunting (family tradition, customs) | ||||

| 5. Electric car

|

||||

| 6. LGBTQ / criminalization

|

- In a neighborhood, in upstate New York, a parent demands clean water for the household. Is clean water in the household a private or public issue? Why? Why not?

- Due to custom and family tradition a father marries off his child at the age of 13. Is child marriage a private or public issue? Why? Why not?

- Egyptians no longer get crop subsidies, in particular for wheat. This made the price of bread skyrocket. Is the wheat subsidy a private or public issue? Why? Why not?

- In the Arctic, whale hunting is part of indigenous peoples’ survival and culture. Is whale hunting a private or public issue? Why? Why not?

- One individual buys an electrical car. Is the purchase of an electrical car a private or public issue? Why? Why not?

- Uganda’s government criminalizes LGBTQ individuals. Is it possible for LGBTQ individuals to be free? Is this a private or a public issue? Why? Why not?

Everyday life is political and the private is political. Private decisions have political implications. Political decisions have private consequences. Everyday mundane activities both have an effect on and are affected by politics. The realm of global politics has imprinted individual perceptions about what happens in the world.

Global Politics

Sometimes global events create a shockwave that leaves long-term scars, like the Darfur genocide. Other times global events appear so distant that their effects are not felt locally, like the December 2004 tsunami off the coast of Sumatra. Global events appear distant, yet a war in the Middle East affects oil production in the United States, and consequently, the prices of gas at the pump. The effects of the coronavirus on the global economy are felt by companies like Apple, which have to report adjustments to their earnings due to their dependence on Chinese production and development of products. The pandemic has an effect on European travel, and thus, on European countries that depend economically on tourism, like Greece and Portugal. The common thread among these, and others, is how unexpected events have an effect on political life. One must ask the question: Do states have the capacity to manage effectively and prudently these unexpected global occurrences? An individual might say: “What do I care?” Or “Nothing I can do will make a difference.” The argument is less about how much one should care, but how these events affect one’s daily lives. Education has been redefined to study remotely. Much like education, working from the office has been transported virtually into one’s house or flat. These issues have a direct impact in the lives of every person. Apathy and disinterest do not promote effective solutions to global problems that have local consequences.

Student Activity

Make a list of two or three global events that are or were unexpected; for example, Gandhi’s salt march of 1930 was an act of civil disobedience that was unexpected. Another example is the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. Describe another two or three events in a few sentences.

The art of politics is to turn unexpected events (perhaps like those on the students’ lists) into unexpected actions. Politics touches everyone at different levels. Global events have an opportunity to create global politics. The question remains how does global politics affect one’s daily life? How do the events bring perspective to a person’s politics? What is the government’s response to global politics? How does the government decide which global event gets attention or gets a response? What are the effects of government responses or lack thereof on individuals?

Stefania Bracco’s research suggests that when a disruption to the supply of fuel occurs the correlation to higher food prices is strong. Bracco states that:

In the 2007-2008, high fuel prices induced a sharp increase in food prices, pushing millions of people into hunger and generating uprising and protest in many developing areas. Despite a decrease due to the global crisis in 2009 and recent low levels in 2015, high international prices produce problems for poor food-net-consumer people. A general increase in food prices exacerbates world hunger.[13]

World events have a direct impact in people’s lives, and in more extreme cases, their ability to survive. It is foolish to assume that events in Mogadishu have no impact in the daily lives of other Africans, Europeans, or Americans. Because world events appear so distant, one way that individuals have learned how to place themselves as part of the global community is by their use of social media.

Social media

Social media is discussed here as a space for democratic activity. It is an open forum of ideas, marketplace of ideas. It is a more democratic space than the ancient Agora. The flow of information has limited censorship. For good or for bad, social media has been a means to socialize the electorate. When it comes to politics and to campaigns, social media is open to who wants to pay for an ad regardless if the information is truthful or not. For example, Mark Zuckerberg has decided on controversial policies for Facebook. He “has no intention of changing the company’s policy on political advertisements, which means that the social network will not ban them or fact-check them.”[14] Jack Dorsey from Twitter announced that political ads are not allowed in its social media platform.[15] Which social media platform is right about political ads? Should Facebook have responsibility for political ads– meaning to check them for lies or inaccuracies? What are the responsibilities of each social media platform towards its readers and those who put trust in the system for information? Democracy requires political participation and information. Individuals have a right to know how information is being disseminated.[16] Regardless of its original intent, social media today is the papyrus of old. Should social media be held accountable to what it publishes much like other printed Media or TV? Accuracy and transparency are important to democracy and to politics. Politics is taking place in these abstract cyber spaces yet consumers of this sort of information cannot hold anyone accountable for the information they are receiving. How is this democracy?

Another aspect of social media is having too much information. Because of the amount of information available to individuals, it becomes difficult to identify what is legitimate journalism. Another issue related to the amount of information is how individuals self-select information based on their beliefs and values. In general, individuals do not seek information that challenges their beliefs. But rather, most consumers of information do not really consume information, instead they procure to reaffirm their beliefs and values.[17] How much information is too much? What is the difference between being curious and seeking information? How do we solve the issue of information bubbles that “we like because it reaffirms what we believe?” How do we understand politics and political issues while facing the following: misinformation, disinformation, fake news?[18] Learning, practicing, and being educated on issues is a start for citizens to gain knowledge. Being a good person and a good citizen is geopolitically contextualized. Civic engagement involves promoting political understanding, voting, and gaining knowledge about politics and all are key to a successful healthy polis.

Civic Education and Politics

The research on civic education is vast. Why not start with Aristotle? Aristotle suggested that the good citizen and the good person were not one and the same. For Aristotle, the different characteristics and functions are directly correlated with space and with type of government. How does a person learn to become a good citizen? How does an individual learn how to be a good person?

The correlation between civic education and civic engagement is a problem that academics continue to tackle. Education as a variable is positively correlated with voting. The higher the education level a voter has, the more likely they are to vote. In other words, voting participation can be predicted based on level of education. The OECD Better Life Index measurement for Civic Engagement supports the correlation between education level and voting. The OECD measure of civic engagement for voter turnout shows Australia (which has compulsory voting) attaining 8.9 out of 10. Chile, on the other hand manages only a 1.0 out of 10—at the lowest end of civic engagement.[19] The United States ranks 7.0 out of 10. If education is an important consideration, then Australia ranks 8.6, Chile 4.5, and the United States ranks 7.0. The suggestion here is not to draw conclusions, but to think of the many possibilities around civic engagement, the teaching of politics, and education of voters.

Student Activity

- Write down when your first experience with politics took place in an educational setting (the level of schooling).

- What did you learn? What ideas? What concepts?

- Identify one political idea and explain how you would teach it.

Civic education must promote active citizenship and participatory democracy. Students in all grades of school should and must be active learners and be able to advocate for the issues that interest them. Students need skills that empower them to solve problems of collective action. Civic education does not end with high school or college graduation. Once learned, it must be practiced during one’s lifetime. Teaching civics is not enough. In order to be an active citizen, it is important to recognize how government operates in an individual’s daily life outside of the classroom.

In 1937, John Dewey stated that, “democracy is much broader than a special political form.”[20] This is what civic education needs to include, and classrooms must produce individuals who understand what politics is.

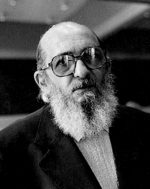

Paulo Freire argues for an education that is communicative: “Liberating education consists in acts of cognition, not transferals of information.”[21] In order to promote civic education, students must not be taught, but must be provided with space and tools to operationalize their vision of civic engagement. One way to create curiosity in students is for teachers to end the practice of simply depositing knowledge and to allow students to practice democratic tolerance of differences. Freire suggests that: “Often, educators and politicians speak and are not understood because their language is not attuned to the concrete situation of the people they address. Accordingly, their talk is just alienated their alienating rhetoric.”[22]

Civic education needs to consider everyday politics. “The core of civic education may be learning to talk and listen with other people to public problems.”[23] Civically minded students create civically minded individuals who vote, participate in making elected officials accountable, and voice their opinions.

Conclusion

Educating individuals is essential for maintaining a participatory democracy. “What is politics” remains undefined. There is not a simple definition or answer. Politics is multifaceted. Based on the idea that politics is the art of compromise, it is constantly contested. In this context, participating in political life is essential to a healthy political system. The making of politics has to be inclusive to embrace protests such as those of 2020 in the United States and across the world. Politics may be approached in a theoretical and narrow sense as in ancient Greece. Politics may be considered as everyday politics as suggested by de Gouges. While political scientists prefer to measure and to operationalize politics, it is difficult to measure one’s political consciousness. In Saudi Arabia, The Women To Drive Movement[24] signals that paradox. While women have not been allowed to drive until recently, every year a group of women chose to drive and get arrested. In doing so, these women participated in civil disobedience in order to make their situation political. In a democratic system, participation is granted and many times it is taken for granted. It is up to the reader to decide how politics works best to inform one’s political participation. The reader must consider all aspects of “what is politics.

Notes

[1]Niccolò Machieavelli, The Prince, In The Portable Machiavelli, editors and translators Peter Bondanella and Mark Musa, New York: Penguin Books, 1979, 95.

[2] Machiavelli, The Prince, chapter XIX, 142.

[3] Machiavelli, The Prince, chapter IX, 110.

[4] Machiavelli, The Prince, chapters XXIV-XXVI.

[5] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, A Discourse on Political Economy, In The Social Contract and Discourses, translated and introduced by G. D. H. Cole, Vermont: Everyman, 1993, 140.

[6] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract. In The Social Contract and Discourses, translated and introduced by G. D. H. Cole, Vermont: Everyman, 1993, 203.

[7] Rousseau, The Social Contract, 204.

[8] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1958, 7. Conditio sine qua non means a condition without which. Conditio per quam means condition through which.

[9] Olympe de Gouges, “Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizen,” In Women’s Political & Social Thought, editors Hilda L. Smith and Berenice A. Carroll, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000, 151-55.

[10] PBS, “Read the Full Text of Trump’s 2020 State of the Union Address,” Politics, February 6, 2020 https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/read-the-full-text-of-trumps-2020-state-of-the-union last accessed on 11/02/2020.

[11] Lauren Egan, “Trump Calls Coronavirus Democrats’ ‘New Hoax,”” February 28, 2020 https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/trump-calls-coronavirus-democrats-new-hoax-n1145721 last accessed on 11/02/2020.

[12] Kathleen Fifield, “The Trickle-Down Effect of Caregiving on Women,” November 29, 2018 https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/basics/info-2018/women-caregiving-trickle-down-effect.html Last accessed on 11/8/2020.

[13] Stefania Bacco The Economics of Biofuels: The Impact of EU Biogenergy Policy on Agricultural Markets and Land Grabbing in Africa, Routledge: 2016, ProQuest Ebook Central http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cudenver/detail.action?docID=4560369. Created from cudenver on 2020-01-21 20:47:06.), 20-1.

[14] Dylan Byers, “Facebook’s Zuckerberg Holds Line On Political Ads, But Microtargeting Could Change,” November 5, 2019.https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-s-zuckerberg-holds-line-political-ads-microtargeting-could-change-n1076566 Last accessed on 11/8/2020; Rob Price, “Mark Zuckerberg Launched an Impassioned Defense of Political Ads on Facebook, Just Minutes After Twitter Banned Them,” October 30, 2019 https://www.businessinsider.com/mark-zuckerberg-defends-political-ads-after-twitter-bans-them-2019-10 Last accessed on 11/8/2020.

[15] Emily Stewart, “Twitter is walking into a minefield with its political ads ban,” vox.com, November 15, 2019 https://www.vox.com/recode/2019/11/15/20966908/twitter-political-ad-ban-policies-issue-ads-jack-dorsey Last accessed on 11/8/2020

[16] Wen, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170629-the-hidden-signs-that-can-reveal-if-a-photo-is-fake Last accessed on 11/8/2020

[17] Gruen and Townes https://shorensteincenter.org/facebook-friends/ Last accessed on 11/8/2020

[18] Matthew Baum, David Lazer, and Nicco Mele, “Combating Fake News: An Agenda For Research and Action,” Journalistic Practice, Media Business, New Business & Practice https://shorensteincenter.org/combating-fake-news-agenda-for-research/ May 2, 2017, Last accessed on 11/8/2020; Joan Donovan, Testimony in front of the House Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce on January 8, 2020, January 9, 2020 https://shorensteincenter.org/dr-joan-donovan-testifies-to-congress-on-media-manipulation-and-disinformation/ Last accessed on 11/8/2020; “Comparative Approaches to Disinformation,” Berkman Klein Center, October 4, 2019 https://cyber.harvard.edu/story/2019-10/comparative-approaches-disinformation Last accessed on 11/8/2020.

[19] “Civic Engagement,” OECD Better Life Index, OECD, Accessed September 25, 2020 http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/civic-engagement/ Last accessed on 09/25/2020

[20] John Dewey, “Democracy,” In Classics of Political & Moral Philosophy, editor Steven Cahn, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, 1204.

[21] Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York: Continuum, 1997, 60.

[22] Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 77.

[23] Jack Crittenden and Peter Levine, “Civic Education 3.1 Good Persons and Good Citizens,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, August 31, 2018 https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/civic-education/#GoodPersGoodCiti Last Accessed on 09/25/2020.

[24] The Women To Drive Movement, https://oct26driving.com Last accessed on 09/25/2020.

References

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1958.

Bacco, Stefania. The Economics of Biofuels: The Impact of EU Biogenergy Policy on Agricultural Markets and Land Grabbing in Africa. Routledge: 2016, ProQuest Ebook Central http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cudenver/detail.action?docID=4560369. Created from cudenver on 2020-01-21 20:47:06.) last accessed 09/25/2020

Baum, Matthew, David Lazer, and Nicco Mele. “Combating Fake News: An Agenda For Research and Action.” Journalistic Practice, Media Business, New Business & Practice. https://shorensteincenter.org/combating-fake-news-agenda-for-research/ May 2, 2017. Last accessed on 11/8/2020.

Byers, Dylan, “Facebook’s Zuckerberg Holds Line On Political Ads, But Microtargeting Could Change.” November 5, 2019. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-s-zuckerberg-holds-line-political-ads-microtargeting-could-change-n1076566 Last accessed on 11/8/2020

Cahn, Steven M, ed. Classics of Political & Moral Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

“Civic Engagement.” OECD Better Life Index. OECD. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/civic-engagement/. Last accessed on 09/25/2020

“Comparative Approaches to Disinformation.” Berkman Klein Center, October 4, 2019. https://cyber.harvard.edu/story/2019-10/comparative-approaches-disinformation. Last accessed on 11/08/2020

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “The Urgency of Intersectionality.” TED. TED, October 2016. https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare.

Crittenden, Jack, and Peter Levine. “Civic Education 3.1 Good Persons and Good Citizens.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, August 31, 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/civic-education/#GoodPersGoodCiti. Last Accessed on 09/25/2020

de Gouges, Olympe. “Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizen.” In Women’s Political & Social Thought, editors Hilda L. Smith and Berenice A. Carroll, 150-53. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Department of Philosophy, Stanford University. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, 2021. https://plato.stanford.edu/. Last accessed on 09/25/2020

Dewey, John. “Democracy.” In Classics of Political & Moral Philosophy, editor Steven Cahn, 1204-7. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Donovan, Joan. Testimony in front of the House Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Commerce on January 8, 2020. January 9, 2020. https://shorensteincenter.org/dr-joan-donovan-testifies-to-congress-on-media-manipulation-and-disinformation/ Last accessed on 11/8/2020

Egan, Lauren. “Trump Calls Coronavirus Democrats’ ‘New Hoax.”” February 28, 2020 https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/trump-calls-coronavirus-democrats-new-hoax-n1145721 last accessed on 11/02/2020

Fifield, Kathleen, “The Trickle-Down Effect of Caregiving on Women.” November 29, 2018. https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/basics/info-2018/women-caregiving-trickle-down-effect.html Last accessed on 11/8/2020

Freire, Paulo https://www.paulofreire.org Last accessed on 09/25/2020

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum, 1997.

Gruen, Andrew and Aisha Townes. “Facebook Friends? The Impact of Facebook’s News Feed Algorithm Changes on Nonprofit Publishers.” https://shorensteincenter.org/facebook-friends/ October 26, 2018. Last accessed on 11/08/2020

Machieavelli, Niccolò. The Prince. In The Portable Machiavelli, editors and translators Peter Bondanella and Mark Musa, 77-166. New York: Penguin Books, 1979.

OpenLearn. “What Is Politics?” OpenLearn. OpenLearn. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/society-politics-law/what-politics/content-section-0?intro=1. Last accessed on 11/8/2020

PBS. “Read the Full Text of Trump’s 2020 State of the Union Address.” Politics, February 6, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/read-the-full-text-of-trumps-2020-state-of-the-union Last accessed on 11/02/2020

Price, Rob. “Mark Zuckerberg Launched an Impassioned Defense of Political Ads on Facebook, Just Minutes After Twitter Banned Them.” October 30, 2019 https://www.businessinsider.com/mark-zuckerberg-defends-political-ads-after-twitter-bans-them-2019-10 Last accessed on 11/8/2020

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. A Discourse on Political Economy. In The Social Contract and Discourses, translated and introduced by G. D. H. Cole, 127-68. Vermont: Everyman, 1993.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Social Contract. In The Social Contract and Discourses, translated and introduced by G. D. H. Cole, 180-331. Vermont: Everyman, 1993.

Shell, T. M. A Primer on Politics. V 0.0 (Creative Commons Licensing: https://2012books.lardbucket.org 2012).

Sheridan, Dick. “Trash Fight: The Long Voyage of New York’s Unwanted Garbage Barge.” nydailynews.com. New York Daily News, August 4, 2017. https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/trash-fight-long-voyage-new-york-unwanted-garbage-barge-article-1.812895.

Smith, Hilda L., and Berenice A. Carroll, eds. Women’s Political & Social Thought (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), Olympe de Gouges “Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizen,” 150-53.

Stewart, Emily. “Twitter is walking into a minefield with its political ads ban.” vox.com. November 15, 2019 https://www.vox.com/recode/2019/11/15/20966908/twitter-political-ad-ban-policies-issue-ads-jack-dorsey Last accessed on 11/08/2020

The Women to Drive Movement https://oct26driving.com Last accessed on 09/25/2020

Wen, Tiffany. “A Picture May Say A Thousand Words, But What If The Photograph Has Been Fabricated? There Are Ways to Spot A Fake—You Just Have To Look Closely Enough.” https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170629-the-hidden-signs-that-can-reveal-if-a-photo-is-fake June 9, 2020. Last accessed on 11/08/2020

“What Is Intersectionality, and What Does It Have to Do with Me?” YW Boston, March 29, 2017. https://www.ywboston.org/2017/03/what-is-intersectionality-and-what-does-it-have-to-do-with-me/.

Figures – References

Badarne, Mohamed. File: Kimberlé Crenshaw (47078273354). Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, May 26, 2019. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kimberl%C3%A9_Crenshaw_(47078273354).jpg.

de La Tour, Maurice Quentin. File: Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Painted Portrait). Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, July 10, 2012. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean-Jacques_Rousseau_(painted_portrait).jpg.

Dimitrov, Slobodan. File: Paulo Freire 1977. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, December 2, 2008. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paulo_Freire_1977.jpg.

File: Harolddwightlasswell. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, January 18, 2016. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harolddwightlasswell.png.

File: Portrait of Niccolò Machiavelli. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, November 25, 2019. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli.jpg.

File: Young Hannah Arendt. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, August 17, 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Young_Hannah_Arendt.jpg.

Grey, Patrick. Athenian Women at Household Chores. Flickr. Flickr, October 23, 2015. https://www.flickr.com/photos/136041510@N05/22212782509.

Koronaios, George E. File: The Ancient Agora of Athens from Polygnotou Street in Plaka on May 31, 2020. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, May 31, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Ancient_Agora_of_Athens_from_Polygnotou_Street_in_Plaka_on_May_31,_2020.jpg.

Kucharski, Alexandre. File: OlympeDeGouge. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, January 21, 2013. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:OlympeDeGouge.jpg.

Library of Congress. File: John Dewey Cph.3a51565. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, August 4, 2019. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Dewey_cph.3a51565.jpg.

Miller, Gary. File:AT STATEN ISLAND LANDFILL. CARTS HEAPED WITH GARBAGE BROUGHT BY BARGE FROM MANHATTAN ARE ABOUT TO DUMP THEIR LOADS AT… – NARA – 549794. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, October 24, 2011. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AT_STATEN_ISLAND_LANDFILL._CARTS_HEAPED_WITH_GARBAGE_BROUGHT_BY_BARGE_FROM_MANHATTAN_ARE_ABOUT_TO_DUMP_THEIR_LOADS_AT…_-_NARA_-_549794.jpg.

Skerrit, Roosevelt. File: Morning after Hurricane Maria (37372721465). Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, March 10, 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Morning_after_Hurricane_Maria_(37372721465).jpg.

Vencel, Milei. File: Phuket after Tsunami. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Commons, December 27, 2016. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phuket_after_tsunami_(2004).jpg.