What Is NAM?

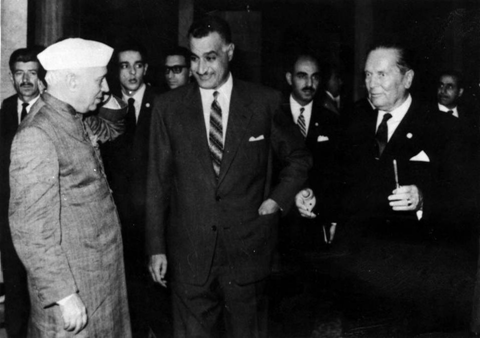

The Non-Aligned Movement developed within the context of two of the most important global developments of the second half of the 20th century: decolonization and the Cold War. This movement initially reflected the concerns of Asian and African countries, primarily former colonies, who were concerned with issues of resisting the influence of the major powers, maintaining their own independence, and opposing colonialism. Building off the “Five Principles of Coexistence” developed in bilateral talks between India and China, the leaders of Burma, Ceylon, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan invited representatives from twenty-four other countries in Asia and Africa to attend the initial conference in Bandung, Indonesia. Gamal Abdel Nasser (Second President of Egypt), Sukarno (First President of Indonesia), and Jawaharlal Nehru (first Prime Minister of India) led the conference from April 18-24, 1955.

The Bandung Conference

The Bandung Conference focused on how to maintain peace, the role of the Third World in the Cold War, economic development of member states, and decolonization. The core principles developed at the meeting reflect these concerns: self-determination, respect for political sovereignty, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, and equality among members. These were all critical issues in the eyes of states just emerging from long periods of colonial rule and reflected the concerns of Asian and African leaders that Western powers continued to make decisions that affected them in the context of the Cold War without consulting them.

The delegates wanted to maintain their neutrality, and also debated whether they should condemn Soviet policies in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, ultimately deciding to adopt a stance against “colonialism in all its forms.” China played a key moderating influence in this regard. Premier Zhou Enlai personally took part in these efforts, which helped quiet concerns of anti-communist representatives at Bandung. Zhou even took the extraordinary step of publicly signing a statement that asserted that the primary loyalty of overseas Chinese was to their home nation. This statement may not seem important to those living in countries with small Chinese immigrant populations, but was a major source of concern for Indonesia and other nations with large ethnic Chinese minorities. The conference ended with a joint proclamation of the movement’s objectives: promotion of economic cooperation, protection of human rights, respect for self-determination, desire for an end to racism, and peaceful coexistence. Bandung was followed by the Afro-Asia Peoples Solidarity Conference (1957) and the Belgrade Conference (1961), which really launched NAM.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the primary concerns of the NAM was fostering peace, which led most of the states involved to adopt a pragmatic type of neutrality, in which each member adopted foreign policies that its leaders believed were in their country’s best interest. This interest in pragmatic neutrality reflected current concerns, which included the Hungarian Revolution (1956) and the Suez Crisis (1956). Member states were also highly concerned about on-going tensions between the United States and the People’s Republic of China, relationships between Third World countries and the United States, opposition to colonialism (especially in Algeria), and the possibility of nuclear war.

The Havana Declaration

After the Bandung and Belgrade Conferences, NAM members hoped to focus on using Third World collaboration to reduce reliance on the West, which laid the foundation for NAM. It is possible to understand the movement as a pragmatic effort to avoid being drawn into the conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. Despite the initial motivation to promote peace, NAM became increasingly radicalized during the 1970s in its critiques of the USA and USSR. The critiques of the superpowers were in some respect the result of the addition of more newly independent African nations, and a shift toward a focus on national liberation movements. The Havana Declaration (1979) reflected this turn away from coexistence.

In the 1979 Havana Declaration, Fidel Castro argued that the purpose of the movement was “to ensure national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity, and security” of members in the struggle against imperialism, colonialism, racism, and hegemony by great powers. At that time two-thirds of the United Nations were members of NAM, and they represented fifty-five percent of the global population. However, the movement was hurt by internal conflicts among its members, especially in their responses to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1980, which incensed Middle Eastern leaders.

During the 1970s and 1980s, NAM sponsored campaigns aimed at restructuring global commerce and finance. Reform of the United Nations was also an important goal of NAM members during this time period, as they argued that powerful states used the UN to violate its founding principles. These members sought increased transparency and democracy in the decision-making processes at the UN and made the United Nations Security Council a special target of their reform agenda.

It is difficult to evaluate the success or failure of NAM because its aims were so tied to the Cold War. There are several important criticisms of the organization: that it had poorly defined goals, that it had no real ideology, and that most policies were related to individual self-interests of the member states. One oft-cited example of this is of India’s decision to accept American military assistance during its 1962 war with China. NAM has also been criticized for its inability to develop a coherent bloc of leaders with similar goals and methods. This lack of a coherent leadership group was due in part to the fact that becoming a third powerful bloc along with NATO or the Warsaw Pact was not one of the organization’s goals. It also did not develop its own ideology, largely due to pressure from the two superpowers. NAM was essentially an effort by Third World leaders to escape from the US vs. THEM dynamic of the Cold War. As such, many scholars argue, their stance was not really one of principled neutrality, but of acting in their own national interests.

Fisher, “Non-Aligned with Reality: How a Global Movement for Peace Became a Club for Tyrants”

Results of NAM

Egypt and Yugoslavia especially benefited from their positions in the Non-Aligned Movement, as they became recipients of major diplomatic efforts on behalf of the United States and the Soviet Union. Other NAM members also became beneficiaries of superpower rivalry by attracting more attention than they might have otherwise. At the time of the Bandung Conference, the United States had viewed NAM with caution, thinking that it was evidence of a leftward political shift among the attendees. Bandung and later conferences also had the effect of showing American leaders the potential challenges of supporting decolonization on the one hand, while relying on European colonial powers as important allies on the other. The Non-Aligned Movement also burst onto the international scene at the same time the Civil Rights movement began to pick up steam in the United States – publicity surrounding resistance to desegregation and other rights advances led newly independent countries to question American commitment to liberty and equality. This diplomatic issue helped push the Federal government in the United States to support the Civil Rights Movement in order to maintain its position in the face of criticism from both the Soviet Union and NAM members.

However, just as pressures brought by NAM influenced American policies, so did the reactions of the superpowers affect the Non-Aligned Movement. President Harry S. Truman thought that Yugoslavia, one of the founding NAM members provided a good wedge to use against the Soviet Union and the rest of the Warsaw Pact, and provided the regime economic and military assistance (which ended in 1958 when Yugoslav leader Josep Tito refused to join NATO). American efforts led Yugoslavia to end its support for Communists fighting in the Greek Civil War, and gained its support for the 1955 Balkan Pact. Although American leaders tended to view NAM through the lens of the Cold War – claiming that it slanted toward the Soviets when the organization failed to support U.S. policies – they eventually came to view the movement as beneficial.

Diplomats at the American State Department grouped movement members into three wings – pro-Soviet “extremists”, moderates such as Yugoslavia and India, and “conservatives” such as Zaire, Pakistan, and Singapore. Similarly, the Soviet Union went through phases of greater or lesser support for the NAM, and tended to be more sympathetic toward states that were closest to its own policies and ideas. Stalin generally opposed NAM, while Nikita Khrushchev vacillated between support and condemnation for the Non-Aligned Movement. Regardless, the debate about the organization led to more interest in decolonized states.

References

Evans, Martin. “Whatever Happened to the Non-Aligned Movement?” History Today, December 12, 2007. Accessed May 25, 2015. http://www.historytoday.com/martin-evans/whatever-happened-non-aligned-movement.

Fisher, Max. “Non-Aligned With Reality: How a Global Movement for Peace Became a Club for Tyrants.” The Atlantic, August 29, 2012. Accessed May 25, 2015. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/08/non-aligned-with-reality-how-a-global-movement-for-peace-became-a-club-for-tyrants/261737/.

Mišković, Nataša, Harald Fischer-Tiné, and Nada Boškovska Leimgruber. The Non-Aligned Movement and the Cold War: Delhi, Bandung, Belgrade. London: Routledge, 2014.