Social Darwinism

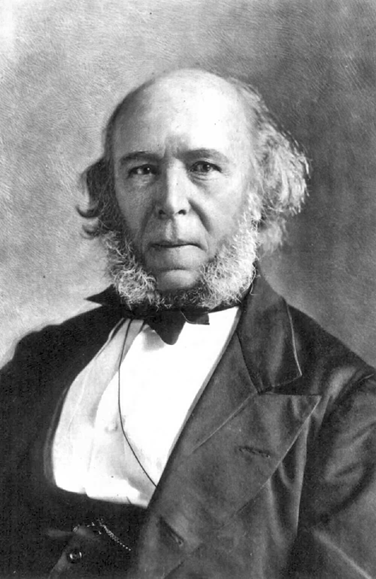

Herbert Spencer, the theorist behind Social Darwinism, argued even within societies, that the strongest would survive and the weak would decline. The state should not be allowed to interfere; it was a natural process. Extreme nationalists and other racist groups used Social Darwinism as an excuse to persecute others – racism was dramatically revived and strengthened by pseudo-scientific biological arguments. It is important to separate Social Darwinism from Darwin’s theory of evolution – Darwin was talking about how species evolve over extremely long periods of time. He did not apply this theory to social and ethnic groups. That fell to Herbert Spencer. Spencer argued that progress in a society came from the struggle for not only the society to live, but also for the members of society to struggle to succeed. This idea argues against charity from individuals or groups, or welfare programs run by the government. Social Darwinists argue that providing these support systems discourages people from attempting to succeed. Others subscribing to this belief, like American President Theodore Roosevelt, contended that nations had to compete with other nations in order to maintain their strength. Otherwise, they would become soft and decadent.

Africa

After decades of armed resistance to European rule that ultimately proved fruitless due to European military technology and organization, Africans turned to new methods of resisting foreign domination. One important method was simply to move. Both seasonal and permanent mass migrations provided Africans with a way to avoid some colonial abuses. When colonizers forcibly recruited laborers during the dry season in the Zambezi Valley, fifty thousand people fled to Zimbabwe and Malawi. In another episode, thousands migrated from the Ivory Coast to Ghana to escape French military recruitment for World War I. When the Kikuyu lost their lands in Kenya to white settlers, they moved to urban areas to find work.

Africans also turned toward indigenous religious movements as a means of anti-colonial expression. Both independent Christian churches and African sects that combined elements of both Christian and African traditions had a millennial outlook. These movements restored Africans to leadership positions within their own religious communities and sometimes became the centers for developing anti-colonial ideas. Reverend John Chilembwe preached that colonialism was counter to the tenets of Christianity, ultimately leading a revolt against colonial authorities in Malawi in 1915.

Before and after World War I, Africans used indigenous newspapers to counter the media outlets of colonial powers in West Africa, North Africa, and South Africa. These papers provided Africans a voice when they were excluded from government, and allowed them to criticize forced labor, their inability to participate in politics, high taxes, and their lack of access to education. After the end of World War I, Africans relied on clubs and associations to develop and spread anti-colonial ideas. The National Congress of British West Africa, founded in 1919 by J. E. Casely Hayford promoted pan-Africanism by representing four colonies. It also contributed to the formation of more local radical political parties such as the West African Youth League. We will dive more into African Nationalism in this Module’s Exploration.

Asia

China

China’s tumultuous 20th century really began with its defeat by Japan in 1895, which led foreign powers to begin carving territorial concessions out of China for their trade missions. Western aggression in asserting their special status led to an uprising by a group they referred to as the Boxers due to their use of martial arts techniques in warfare. The Boxers, formally known as the “Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists” combined martial arts and religious beliefs that included rituals and spells that they believed would make them invulnerable to Western weapons. The Boxers led a movement that relied on both encouragement from Dowager Empress Cixi and resentment of Western powers due to their on-going humiliation of China after the Opium Wars to gain its impetus, attacking European establishments and individuals. The uprising was eventually defeated by Western powers, which seized control over Beijing in the process. After seizing Beijing, European countries not only insisted that China pay a large indemnity to compensate for their losses during the conflict, but also asserted the right of keeping military forces in Beijing itself to protect their interests.

In China, the result was that most traditionalists accepted the necessary reforms in Chinese society. Among the reforms were changes in education (women were now admitted), military organization which was based on Japanese practices, and politics. In the political realm, the established examination system for potential bureaucrats was abolished, replaced with recruitment from schools that had adopted Western educational models. In addition, regional assemblies were instituted, with representatives elected locally. The cumulative effects of these changes was a revolution in 1911, which ultimately resulted in the downfall of the Qing and the Chinese imperial system.

Despite efforts to provide unified governments for China, it quickly became dominated by warlords who claimed control over various provinces. Despite this, reformist ideas continued to spread from intellectuals in Beijing throughout China. One of the most important was the May 4th Movement, discussed above, but after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Marxism gained favor. Marxist philosophy did not fit naturally into the Chinese environment any more than they had in Russia, but V. I. Lenin’s definition of imperialism as the crisis stage of capitalism allowed Chinese thinkers to blame all of the country’s problems on Europeans, and offered the hope that they could jump straight from feudal oppression to communist “freedom” without muddling through the capitalist system.

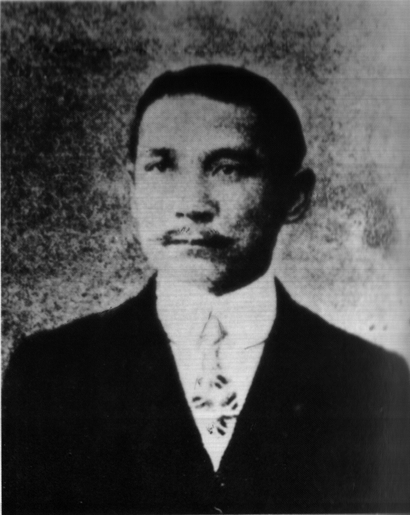

Still, communism took a long time to develop into China’s dominant ideology. Sun Yat-Sen returned to China in 1916, and with support from the Soviet Union developed a nationalist party known as the Guomingdang, or GMD. Focusing on an anti-imperialist message, Sun developed the “three principles of the people,” including nationalism, prosperity, and individual rights. Sun and his primary subordinate, Chiang Kai-shek created a military academy at Huangpu to train the officers of a nationalist army. When Sun died in 1925, Chiang Kai-shek took over as leader of the GMD, and its army of 100,000 men.

Vietnam

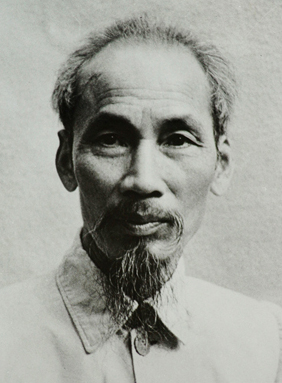

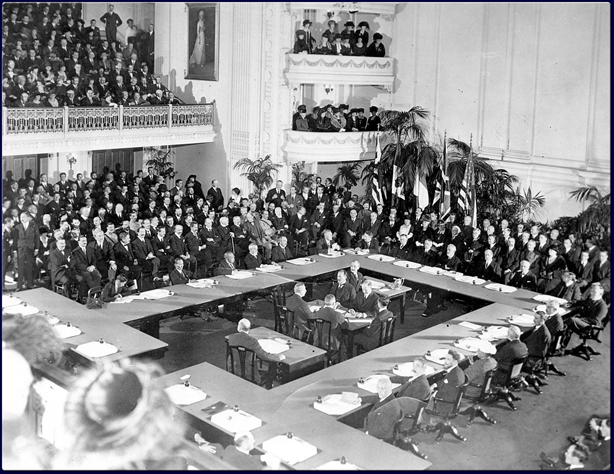

Vietnamese nationalists were also inspired by two developments in Europe. The most obvious was American President Woodrow Wilson’s declaration of support for the self-determination of all peoples and his promotion of the Fourteen Points at the Paris Peace Conference. Wilson also pushed European powers to prepare their colonies for independence, but France and Great Britain wanted to keep their colonies for economic reasons, so these ideas had no immediate result. Ho Chi Minh and other Vietnamese nationalists took Wilson’s rhetoric to heart, though.

Ho tried to appeal directly to Wilson for aid, both in person and in writing but was turned away without seeing Wilson. Desperate to gain some recognition, Ho sent Wilson and French officials his pamphlet “Eight Claims of the Annamite People,” which advocated for free speech, freedom of the press, and free association in Vietnam. The establishment of the protectorate system, and giving Japan Germany’s Chinese possessions, showed Ho that he would have to find non-diplomatic solutions to gain Vietnamese independence. That led him to join the French Socialist Party. When the Communist wing advocated for immediate independence for the colonies, Ho joined them and helped found the French Communist party in 1920, becoming their expert on colonial matters. Ho had also read Lenin’s account of the 1917 Russian revolution and been impressed both by Lenin’s patriotism and the Bolsheviks’ ability to motivate the masses.

His education and experiences led Ho to believe that imperialism was the result of capitalist economic systems. However, despite years of working for Communists to promote revolutions, Ho Chi Minh was primarily a Vietnamese nationalist. The Russian Revolution did, however, provide him with a blueprint for a Vietnamese revolution, and he planned to return to Vietnam to lead it.

Macrohistory: French Colonialism in Vietnam

Japan

By the 1920s, Japan’s parliament had developed into a stable and effective institution, and Japan’s military began to exert increasing amounts of influence even within the parliament. In 1932, military officers began to supplant the heads of political parties in the office of Prime Minister. As a result, Japan engaged in wars with China, the Soviet Union, and the United States. Military domination of the government came slowly and was built, in part, on the military’s resentment of its loss of stature and prestige during the 1920s. Japanese soldiers were the product of a system of universal conscription and attended their own schools that focused on different values than civilian educational institutions in Japan. Soldiers began to see themselves as the heirs of the founders of modern Japan and contrasted their loyalty to the Emperor with the political partisanship in the parliament. Despite political changes during the first two decades of the 20th century, the General Staffs were responsible only to the Emperor, not to the civilian political leadership.

Militarization spread as a result of a series of crises, beginning in Manchuria, which Japan had seized in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. The high cost in lives that it paid for Manchuria led Japanese leaders to claim the same rights as European powers in their colonies around the world. However, Chinese nationalists posed a challenge to this status when they unified China and marched north toward Manchuria. To keep control of Manchuria, which Japan saw as an important way to protect its colony in Korea from external powers, the army took over Manchuria in 1931 and proclaimed it independent the following year. The conflict over Manchuria led Japan to leave the League of Nations when other members condemned its actions there.

Macrohistory: Japanese Politics and Society, to 1927

Latin America

Although Latin American countries gained independence from Spain and Portugal in the 19th century, there was a resurgence of anticolonialism in the early 20th century. Revolutionary leaders redefined colonialism as economic and cultural dependence; politics, global capitalism, and culture were influenced by external actors (Elam). Many leaders embraced anti-capitalist, revolutionary ideas through the writings of Trotsky, Lenin, Gramsci, Gandhi, Mao, and Irish revolutionaries. These leaders included Emiliano Zapata of Mexico, José Carlos Mariátegui of Peru, Fidel Castro of Cuba, and Che Guevara of Cuba (Elam).

Macrohistory: Economic Depression and Politics in Latin America

References

Cobb, Charles, Jr. “Project MUSE – Africa’s Agitators: Militant Anti-Colonialism in Africa and the West, 1918–1939 (review).” Project MUSE – Africa’s Agitators: Militant Anti-Colonialism in Africa and the West, 1918–1939 (review). April 1, 2010. Accessed May 25, 2015. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/384941.

Elam, Daniel J. “Anticolonialism.” University of Virginia Global South Studies. Accessed August 10, 2018. https://globalsouthstudies.as.virginia.edu/key-concepts/anticolonialism.

Talton, Benjamin. “African Resistance to Colonial Rule.” African Resistance to Colonial Rule. Accessed May 25, 2015. http://exhibitions.nypl.org/africanaage/essay-resistance.html.