2

2.1 Introduction

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understand the US court system and how it affects the conduct of businesses.

- Understand the three branches of government and how they check and balance each other’s powers.

- Explore the state and federal court systems.

In the United States, law and government are interdependent. The US Constitution establishes the basic framework of the federal government and imposes certain limitations on the powers of government. In turn, the various branches of government are intimately involved in making, enforcing, and interpreting the law. Most law comes from Congress and the state legislatures. Courts interpret the laws and apply them to cases.

Laws are meaningless if they are not enforced. Companies have to make many decisions daily, from product development to marketing to maintaining growth. These decisions are based on financial considerations and legal requirements. If a company violates a law, it is often held accountable through litigation in courts.

2.2 Separation of Powers

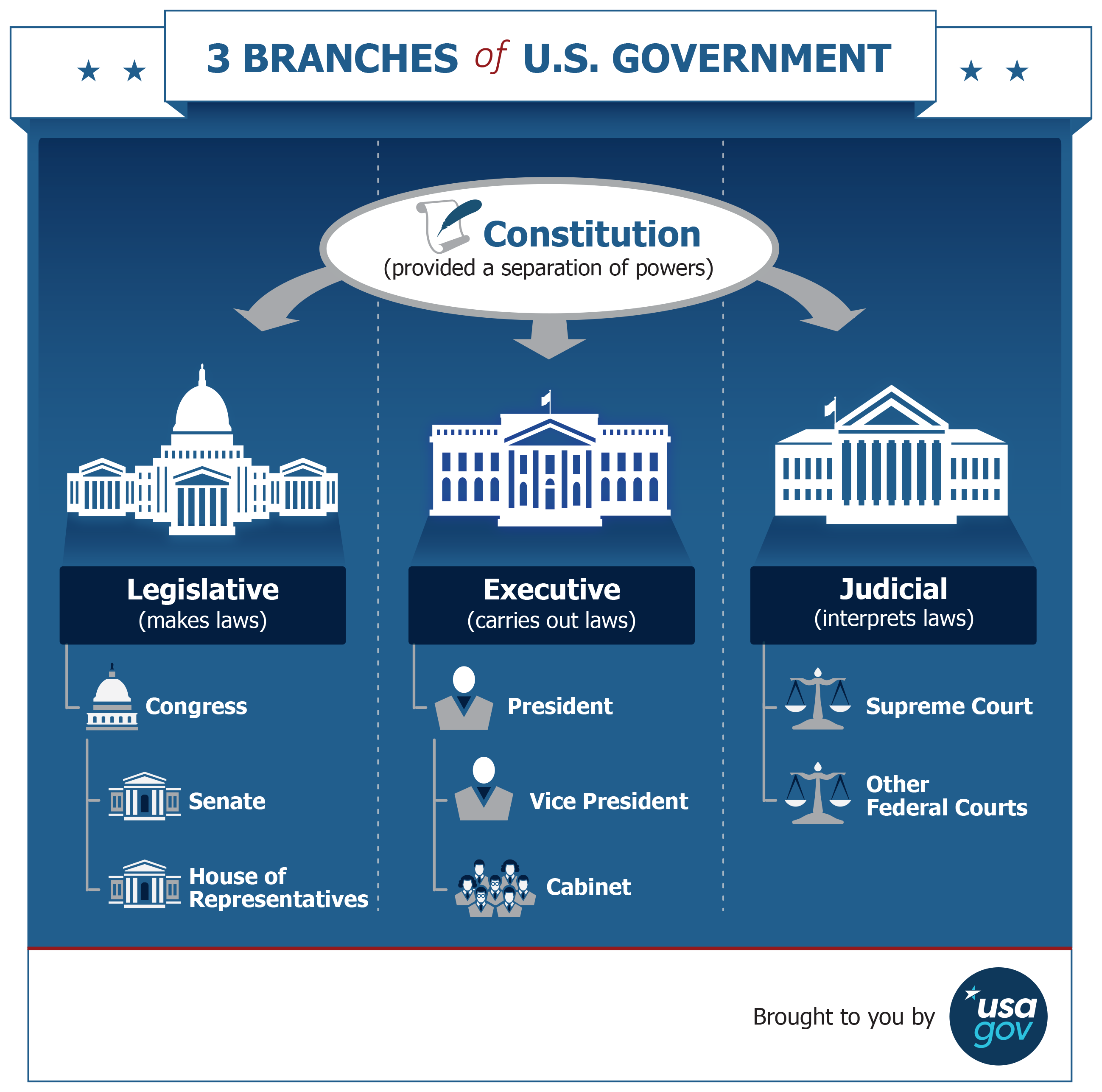

Under the US Constitution, power is separated among three branches of government. Article I of the Constitution allocates the legislative power to Congress, which is composed of the House of Representatives and the Senate. Congress makes laws and represents the will of the people. Article II of the Constitution creates the executive power in the president and makes the president responsible for enforcing the laws passed by Congress. Article III of the Constitution establishes a separate and independent judiciary, which is in charge of applying and interpreting the meaning of the law. The US Supreme Court is the highest court in the federal judiciary and consists of nine Justices.

Figure 2.1 Separation of Powers of the Branches of the Federal Government

The Constitution is remarkably short in describing the judicial branch. Under the Constitution, there are only two requirements to becoming a federal judge: nomination by the president and confirmation by the Senate. Article III provides: “The judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” The Constitution also guarantees that how judges decide cases does not affect their jobs because they have lifetime tenure and a salary that cannot be reduced.

Separation of powers is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

Marbury v. Madison

In 1800, the presidential election between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson nearly tore the nation apart. John Adams was the President and his Vice-President, Thomas Jefferson, ran against him. They were both Founding Fathers but were members of different political parties that had opposing visions for the future of the new nation. The election was bitter, partisan, and divisive. Jefferson won but wasn’t declared the winner until early in 1801. In the meantime, Adams and other Federalists in Congress attempted to leave their mark on government by creating a slate of new life-tenured judgeships and appointing Federalists to those positions. For the judgeships to become effective, official commissions had to be delivered in person to the new judges. At the time power transitioned from Adams to Jefferson, several commissions had not been delivered, and Jefferson ordered his acting secretary of state to stop delivering them. When Jefferson came to power, there was not a single federal judge from his Democratic-Republican Party, and he refused to expand the Federalist influence any further.

One Federalist judge, William Marbury, sued Secretary of State James Madison to deliver his commission. The case was filed in the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, who was also a Federalist. In a shrewd move, Marshall ruled against Marbury while declaring that it was the Supreme Court’s role to decide the meaning of the Constitution. This is called judicial review, and it makes the US Supreme Court an equal branch of government to the Executive and Legislative branches. Because President Jefferson won the case, he was willing to accept the Supreme Court’s assertion of power as an equal branch of government.

Checks and Balances

The US Constitution establishes the three branches of the federal government as independent branches with their own authority. The Founding Fathers were fearful of setting up an authoritarian regime, where the rulers of the government are above the law and often rule arbitrarily. Therefore, the Founding Fathers ensured that each branch of government had a “check” on the other two branches in order to “balance” the power of the government among the branches. Therefore, if a president decided to become a dictator, the other two branches could prevent him.

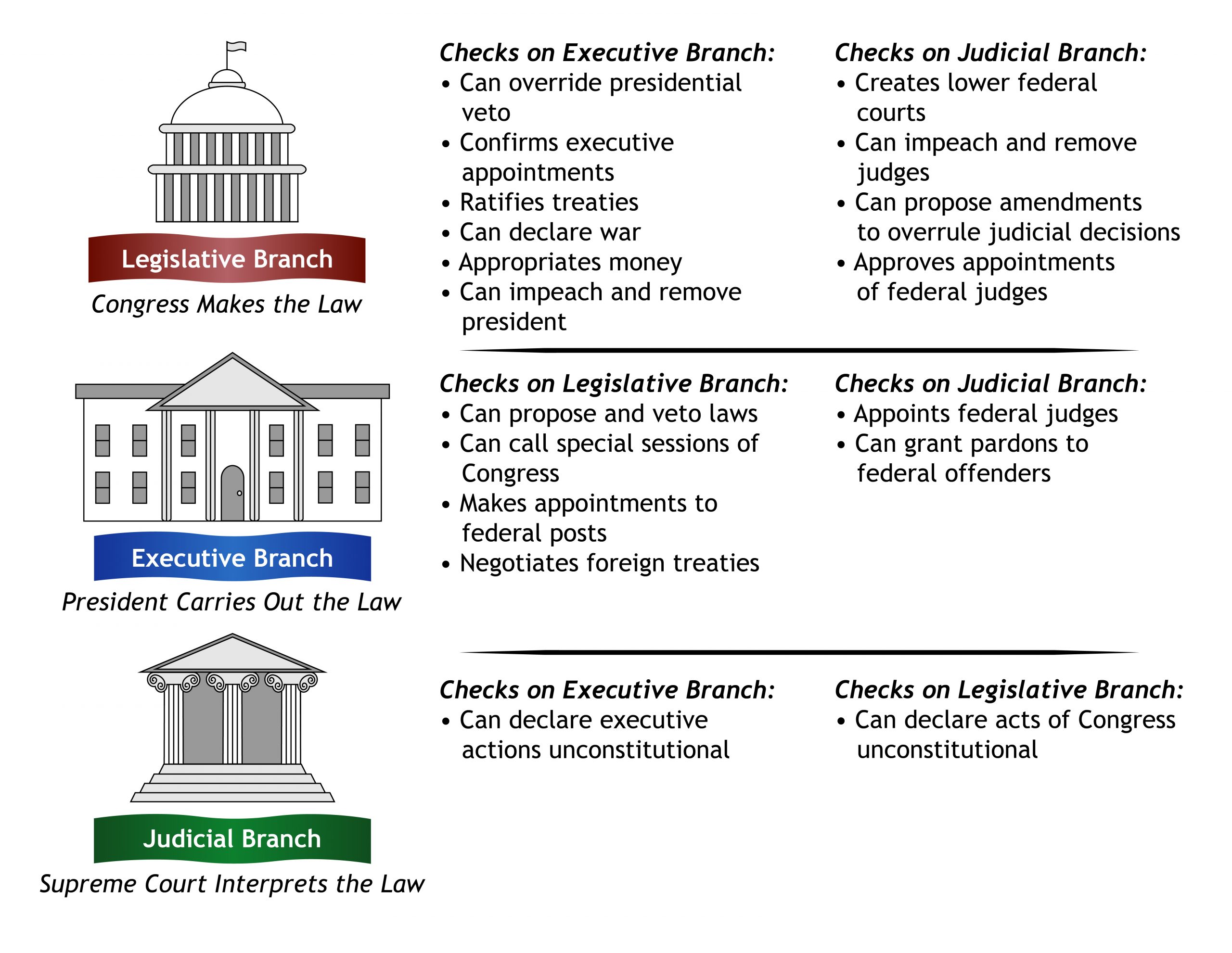

Figure 2.2 Checks and Balances of the Federal Government

Judicial review means that any federal court can hold any act of the president or Congress to be unconstitutional. This is the power of the Judicial Branch to ensure that the Executive and Legislative branches do not overstep their powers and violate the Constitution.

The other branches each have a “check” on the judiciary. For example, the president (Executive branch) can control the judiciary by nominating judges. The president can also pardon those convicted by a federal court. A pardon is an executive order vacating a criminal sentence for a crime.

Congress also plays an important role in “checking” the judiciary. The most obvious role is in confirming judicial selections. In addition to confirmation, Congress also controls the judiciary through its annual budgetary process. Although the Constitution protects judicial salaries from any reductions, Congress is not obligated to grant any raises. Finally, Congress can control the judiciary by determining how the courts are organized and what kind of cases the courts can hear, except for the types of cases the Constitution lists as the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

2.3 Federalism

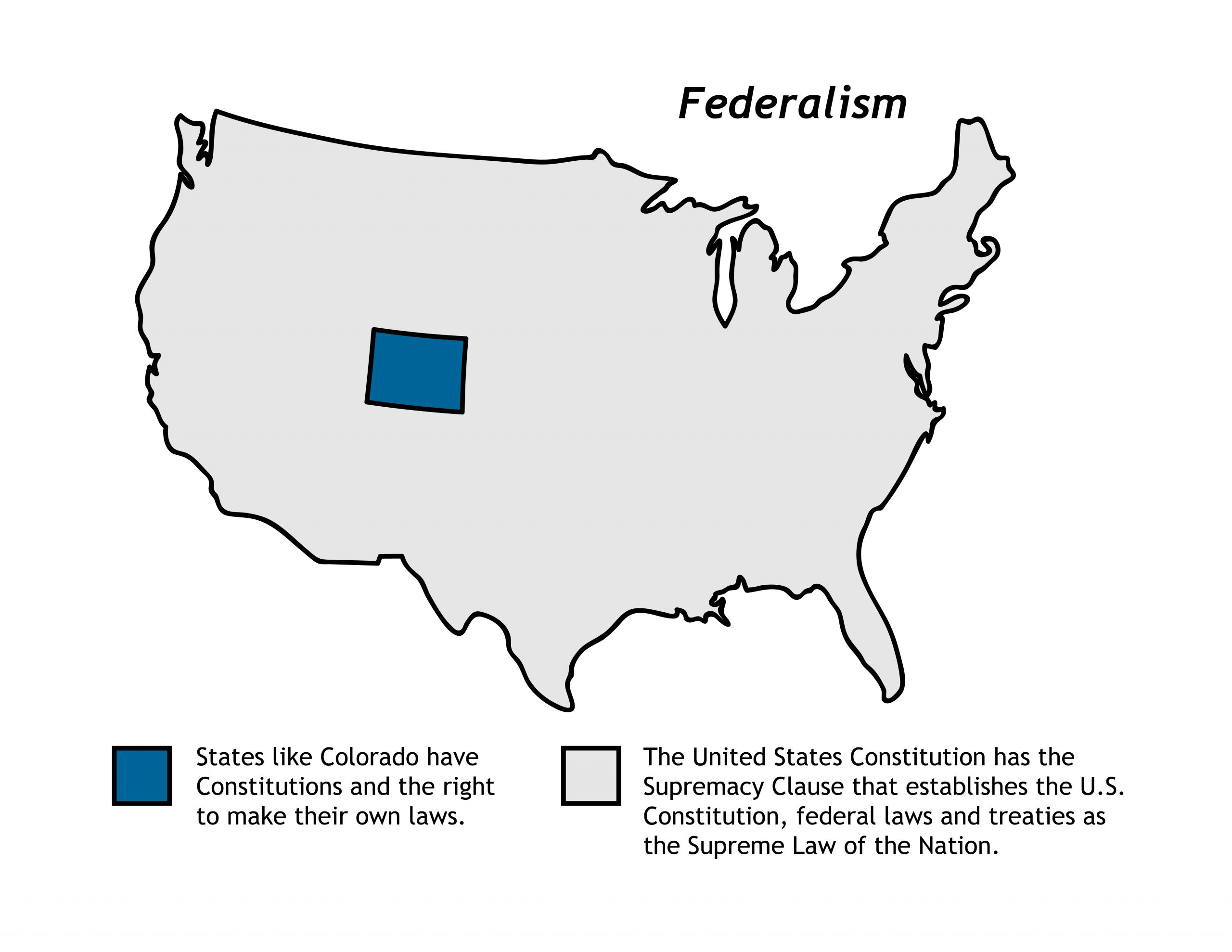

There are fifty-six separate legal systems in the United States: those of the fifty states, the federal government, the District of Columbia, the military, and three territorial systems. Within each legal system is a complex interplay among executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. This division of authority between a central, federal government and state governments is known as federalism.

In the United States, the federal government only has the authority given to it by the states via the US Constitution. If a power is not granted to the federal government, the states retain the power. For example, the federal government cannot tax the exchange of goods between states as “exports.” The Constitution limits the power of the federal government, and the state constitutions limit the power of the state governments.

Figure 2.3 Federalism Between Federal and State Governments

Federalism is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.

Jurisdiction

The authority of a court to hear a particular type of case is called jurisdiction. State and federal courts hear different types of cases, involving different laws, different law enforcement agencies, and different judicial systems. The rules governing the procedures used in these courts are known as civil procedure or criminal procedure.

The rules of subject matter jurisdiction dictate whether a case is heard in federal or state court. The vast majority of civil lawsuits are filed in state courts, including lawsuits involving state laws such as property, contracts, probate law, and torts. State laws also involve most criminal cases, and domestic issues such as divorce and child custody. Torts are any civil wrong other than a breach of contract and include a variety of situations in which people and businesses suffer legal injury. Some states are friendlier toward torts than others, and the resulting patchwork of tort laws means that companies that do business across the nation need to know the different standards they are held to based on the state their customers live in.

Given the wide array of subject areas regulated by state law, most businesses deal with state courts. Federal court subject matter jurisdiction is generally limited to federal question jurisdiction. In other words, federal courts hear cases involving the Constitution or a federal law. Cases involving the interpretation of treaties to which the United States is a party are also subject to federal court jurisdiction. Finally, lawsuits between states can be filed directly in the US Supreme Court.

Sometimes a federal court may hear a case involving state law. These cases are called diversity jurisdiction cases, and they arise when all plaintiffs in a civil case are from different states than all defendants, and the amount claimed by the plaintiffs exceeds seventy-five thousand dollars. For example, a citizen of New Jersey may sue a citizen of New York over a contract dispute in federal court. But if both were citizens of New York, the plaintiff would be limited to the state court of New York. Diversity jurisdiction cases allow one party who feels it may not receive a fair trial where its opponent has a “home court advantage” to seek a neutral forum to try the case.

| Type of Jurisdiction | Description | Minimum Dollar Requirement | Applicable Law |

| Federal Question | Cases involving the US Constitution, treaties, or federal laws & regulations | None | Federal law |

| Diversity of Citizenship | Cases brought between citizens of different states | $75,000 | State law |

2.4 Trial and Appellate Courts

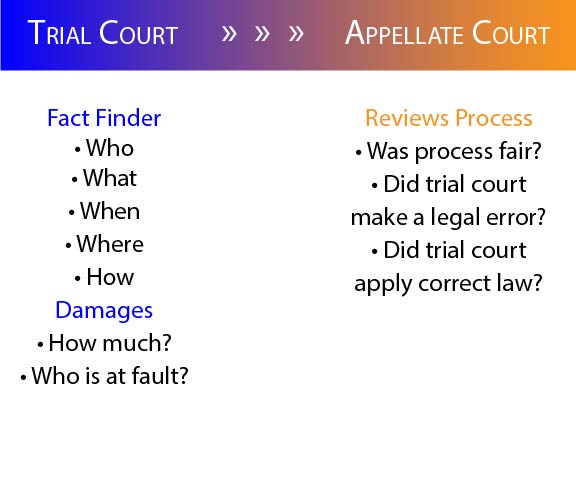

Within the federal court and the state court systems, there are a hierarchy of courts. The first level of court is a trial court or a court of limited jurisdiction such as traffic court and small claims court. Trial courts accept evidence and testimony to determine what happened in a case. Appellate courts review the decisions of the trial court, without holding a new trial, to determine whether the parties received a fair trial and whether the appropriate law was applied.

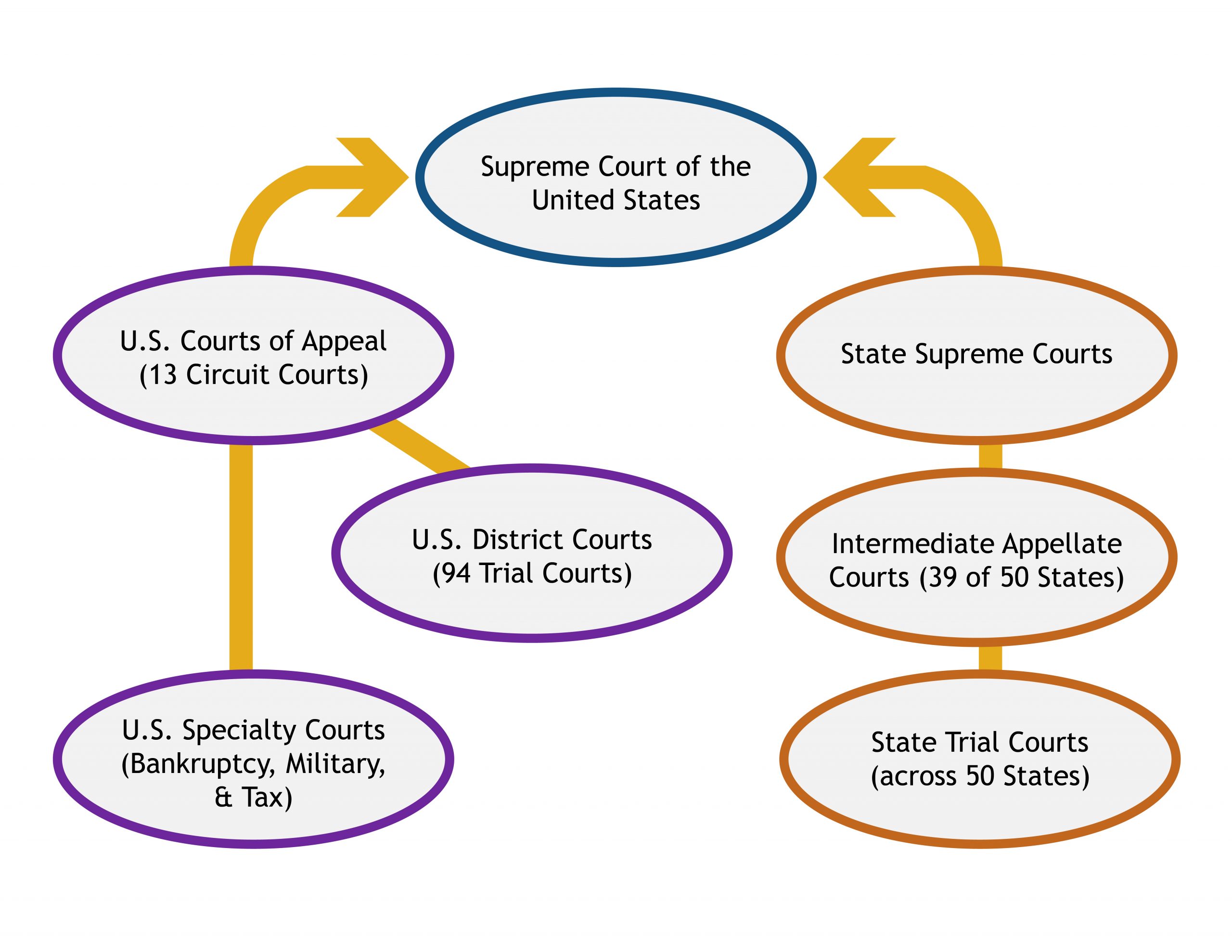

Figure 2.4 Court System Hierarchy

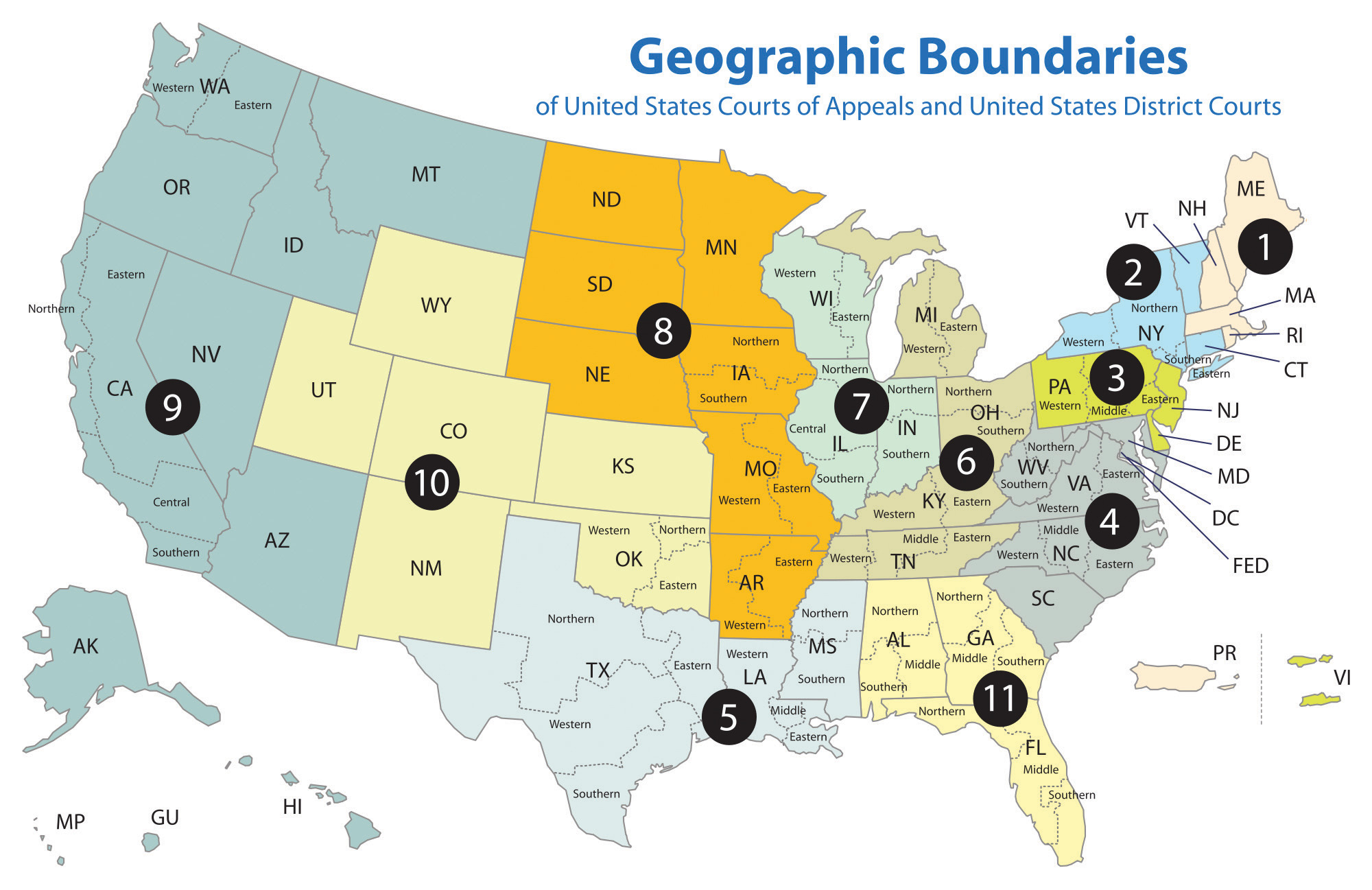

In the federal court system, cases are filed in the US District Court. There are ninety-four judicial districts in the nation, which are named for their geographical location. However, some states with low population have only one judicial district, while more populous states have multiple judicial districts. The US Department of Justice, which acts as the prosecutor representing the federal government in both civil and criminal cases, divides its attorneys among the ninety-four judicial districts.

As a trial court, the US District Courts hear both civil and criminal cases. At trial, witnesses are called and their testimonies are recorded into a trial record. The losing party is entitled to appeal the case to the US Circuit Court of Appeals. There are thirteen circuit courts in the United States. A party losing an appeal at the circuit court level may ask the US Supreme Court to hear its case. However, the Constitution only requires the Supreme Court to hear a few types of appeals.

Figure 2.5 Map of Federal Circuit Courts

In the state court system, a trial court of general jurisdiction accepts most types of civil and criminal cases. These courts are called various names such as superior court, circuit court, or district court. There may be other courts of limited jurisdiction at the state level, such as traffic court, family court, or small claims court. Like their federal counterparts, state trial courts hold trials, and preserve a trial record for review by an appellate court. Finally, in certain state cases that involve a federal constitutional right, a party that loses at the state supreme court level can appeal to the US Supreme Court. These cases typically involve the application of the Constitution to criminal procedure, evidence collection, or punishment.

Whenever an appeal is filed, the trial record is forwarded to the appellate court for review. Appellate courts do not conduct new trials and are unable to recall witnesses or call new witnesses. The trial court’s duty is to figure out the facts of the case—who did what, when, why, or how. This process of fact-finding is an important part of the judicial process, and a great deal of deference is placed on the judgment of the fact finder, which is usually the jury. The issues on appeal are therefore limited to questions of law or legal errors. The deference to the fact finder means that, as a practical matter, appeals are hard to win.

Figure 2.6 Roles of Trial and Appellate Courts

2.5 Concluding Thoughts

The US Constitution establishes the three branches of the federal government and gives them the ability to check each other’s authority. The Judicial branch oversees the actions of the Executive and Legislative branches through judicial review to ensure that they do not violate the Constitution. While not perfect, the US federalist system was designed to restrain governmental power and to prevent the rise of an authoritarian regime.

The Judicial Branch is the only unelected branch of government. Marbury v. Madison established the doctrine of judicial review, which allows courts to determine the final validity of laws as well as the meaning of the Constitution. The president can check the judiciary through appointments and the pardon power. Congress can check the judiciary through confirming judges, administrative control of court calendars and funds, and legislation about the types of cases a court can hear.

There are fifty-six separate legal systems in the United States. Subject matter jurisdiction is the authority of a court to hear a case based on the type of dispute. State law claims are generally heard in state courts, while federal question cases are generally heard in federal court. Federal courts may hear state law claims under diversity jurisdiction. Federal cases are filed in a US District Court and appealed to a US Circuit Court of Appeals. State cases are typically filed in a trial court and appealed to an intermediate court of appeals.