13

13.1 Introduction

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understand the principle of employment at will and the exceptions to the doctrine.

- Learn important employment laws that affect businesses across industries.

- Examine the laws that govern the relationship between employers and employees who belong to a union.

Until the early Twentieth Century, there were not many laws that regulated the employer-employee relationship. The belief was that the free market system would ensure that employers treat employees fairly or else they would not be able to attract and keep good workers. However, the reality of the Industrial Revolution proved that the traditional employment relationship favored the interests of the employers at the expense of workers, including children. As a result, Congress and state legislatures started passing employment and labor laws to protect the interests of employees. Today, employment law is a very robust area of the law that impacts businesses across industries.

13.2 Employment At Will

In general, employees are free to quit a job at any time for any reason, with or without notice. Similarly, employers are free to end a worker’s employment at any time for any reason, with or without notice. This principle is called employment at will. This doctrine is based on the concept that employment is a form of an implied contractual relationship. Therefore, as long as both parties want to continue their contract to work together, the law presumes they will. When one party does not want to continue, then they may end their working relationship.

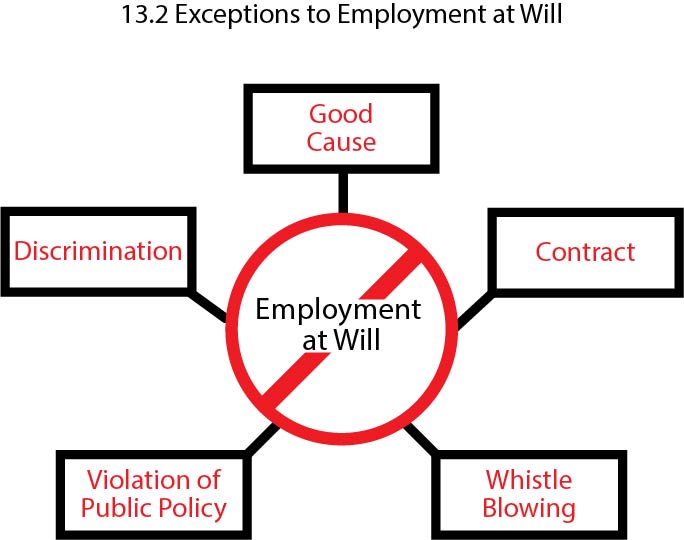

There are five major exceptions to the employment at will doctrine:

- Contract;

- Good cause;

- Discrimination against an employee based on membership in a protected class;

- Violation of public policy; and

- Whistleblowing.

Figure 13.1 Exceptions to the Employment at Will Doctrine

Contract

Employers and employees may modify the employment at will doctrine through contract. In addition to formal, written employment contracts, courts have also enforced oral promises made during the hiring process. Promises made to job applicants are generally enforceable, even when the promises are not approved by the employer’s executives or upper management. Therefore, it is important when hiring employees that companies do not make promises that can be reasonably interpreted to be guaranteed employment or employment for a certain period of time.

Employee handbooks also may create implied contracts that modify the employment at will doctrine. Often handbooks state that the company follows a progressive discipline policy and that employees may only be fired for “just cause” or after receiving warnings, notice, hearing, or other procedures. Policies such as this create an implied contract that require businesses to follow the progressive discipline policy before terminating a worker’s employment, in absence of good cause.

Good Cause

The definition of “good cause” for terminating the employment of a worker varies from state to state. And businesses often define “good cause” in their policies. However, most states recognize the following as good cause to fire an employee without going through progressive discipline first:

- Theft;

- Fraud;

- Damage to company property;

- Being under the influence of illegal drugs or alcohol at work;

- Fighting;

- Threats against other employees or customers;

- Domestic violence;

- Having weapons on premises;

- Unethical behavior; and

- Willful or malicious misbehavior.

Poor performance also constitutes good cause for firing an employee. Employers need to be careful, however, to document the performance issues and to engage in progressive discipline when appropriate. If an employee has not been counseled that their performance is unsatisfactory, then the employee is more likely to bring a charge of wrongful discharge against the employer. Courts are more likely to rule that poor performance constitutes good cause when an employee has notice of the performance issue(s) and has a reasonable opportunity to fix them.

Discrimination Against a Protected Class Member

Anti-discrimination laws make it illegal to take adverse actions against a member of a protected class based on their membership in the class. A protected class is a group of people who are protected by laws that prohibit discrimination based on a personal characteristic, such as race, color, religion, gender, national origin, age or disability.

As discussed in Chapter 14, adverse actions include failure to hire, failure to promote, demotion, and termination of employment. That is not to say that someone who is a member of a protected class may never be fired. Rather, it is illegal to fire them because of their race, color, religion, gender, national origin, age or disability.

Violation of Public Policy

The public policy exception occurs when an employee is fired for:

- Refusing to perform an action that violates a law or public policy; or

- For exercising a legal right or advancing a public policy.

In other words, an employee can’t be fired for refusing to do something illegal or doing something legal that the employer does not want done. For example, an employee cannot be fired for not falsifying reports, for refusing to testify falsely in court, for filing a workers’ compensation claim, or for serving on a jury.

Whistleblowing

A whistleblower is an employee who reports the employer’s illegal behavior to a governmental or law enforcement agency. Many different laws have whistleblower provisions that encourage people who have knowledge of illegal activity to report it without fear of retribution or losing their jobs. Whistleblower protections apply to good faith reports of wrongdoing, even if it turns out that the activity is not illegal. However, whistleblower protection does not usually protect employees who make reports that they either know, or should have known, do not include illegal activity.

13.3 Common Employment Law Torts

Employees may assert various tort claims against their employers. Tort claims are often decided on the basis of generalized duties of care rather than specific types of conduct prohibited by law. Tort claims vary state to state but most states recognize the following claims between employers and employees:

- Negligent hiring, retention, and supervision;

- Negligent investigation;

- Negligent infliction of emotional distress;

- Intentional infliction of emotional distress (also called outrageous conduct);

- Tortious interference with contract and/or prospective business advantage;

- Defamation (libel and slander);

- Invasion of privacy; and

- Fraud.

Torts are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9. However, it is important for businesses to understand that they owe their employees and managers a duty of care. If they violate that duty, then they may be subject to legal liability.

13.4 Wage and Hour Laws

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) is a federal law that was passed in 1938 that nationalized standards for pay, record keeping and child labor for businesses with two or more employees that engage in interstate commerce. The FLSA prohibits “oppressive child labor,” which means that children under fourteen cannot work unless it is a family business, babysitting, newspaper delivery, entertainment, or agriculture. Fourteen and fifteen year olds are permitted to work limited hours after school in nonhazardous jobs, such as retail and restaurants. Sixteen and seventeen year olds may work unlimited hours in nonhazardous jobs.

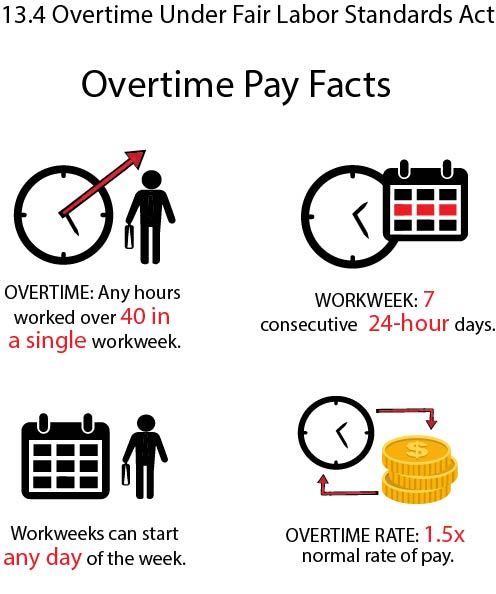

Figure 13.2 FLSA Facts

The FLSA also provides for a national minimum wage and a standard forty hour work week. Under the FLSA, an employee who works more than forty hours is entitled to overtime pay. However, the Act provides exemptions to the overtime requirement. Employees who earn more than a certain amount and perform specific types of work are not entitled to overtime pay.

| Exempt Categories to Overtime Pay under the FLSA |

|

Figure 13.3 Overtime under the FLSA

The Department of Labor (DOL) is charged with enforcing the FLSA and other federal wage and hour laws. As a general rule, federal wage and hour laws do not preempt state and local laws. Therefore, employers must comply with federal, state, and local laws regarding employees’ wages. Many state and local governments have set a higher minimum wage than is required federally. Therefore, businesses must ensure that they comply with all wage and hour laws applicable to them.

13.5 Family Medical Leave Act

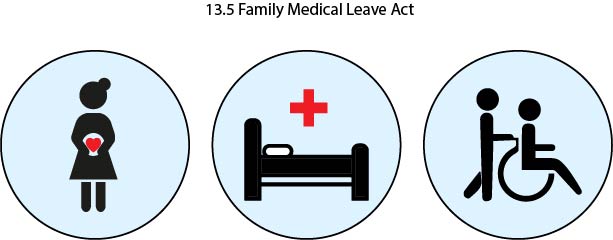

The Family Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) is a federal law that guarantees employees up to twelve weeks of unpaid leave each year for childbirth, adoption, or a serious health condition of their own or their immediate family member. Under the FMLA, a qualifying family member is a spouse, child, or parent. Siblings, grandchildren, and in-laws are not usually qualifying family members. The FMLA applies to businesses with at least fifty workers that engage in interstate commerce.

Figure 13.4 FMLA

An employee must work for the company for at least one year before being eligible to take leave under the FMLA. The Act requires that employees who take leave be allowed to return to the same or equivalent job with the same pay and benefits.

What constitutes a “serious health condition” is a heavily litigated issue. In general, a serious health condition requires continued treatment by a health provider and results in at least three days of incapacitation. Sometimes this aligns with recognized disabilities but it does not always. Also, a condition such as migraines may incapacitate people to varying degrees. To avoid legal liability, businesses should request appropriate documentation from medical providers rather than relying on a subjective determination of what constitutes serious health conditions.

13.6 Occupational Safety and Health Act

In a heavily industrialized society, workplace safety is a major concern. To that end, Congress passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) in 1970. The Act requires employers to provide a workplace that is free from recognized hazards likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees.

Employers must comply with specific health and safety standards for their industry. For example, standards for restaurants differ from standards for health care providers or those for the mining industry. Employers must also keep records of all workplace injuries and accidents, and under some circumstances must automatically report them to the government. Employees may also report violations.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (also known as OSHA) is an agency within the Department of Labor that is responsible for enforcing the Act. The Agency may inspect workplaces to ensure they are safe and impose fines for violations of the Act. The Act also provides for criminal penalties when the violations are willful.

Figure 13.5 Common OSHA Violations

States and local governments also have a variety of health and safety laws and regulations. Therefore, businesses must ensure that they comply with all laws applicable to them.

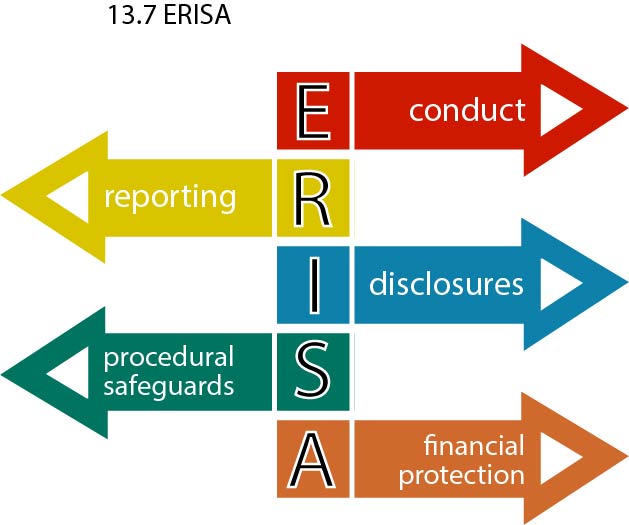

13.7 Employee Retirement Income Security Act

In 1974, Congress passed the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) to regulate employer-sponsored pension plans. ERISA requires employers disclose a large amount of information regarding the funding and vesting of pension plans. This Act was in response to fraudulent handling of pension plans that deprived employees of savings at the time of their retirement.

ERISA also applies to employer-sponsored medical, disability, and welfare benefit programs. Although the Act does not require employers to provide these types of benefits to their employees, if employers choose to do so, ERISA regulates what types of information employees are entitled to, along with their enforcement rights under the plans.

Figure 13.6 ERISA Areas of Regulation

13.8 Workers’ Compensation Laws

Workers’ compensation laws provide payment to employees for injuries incurred at work. In essence, workers’ compensation is a type of no-fault insurance system that every state has. The intent of these laws is to provide quick and efficient delivery of disability and medical benefits to injured workers at a reasonable cost to employers.

Figure 13.7 Workers’ Compensation

Workers’ compensation is the exclusive remedy for injury claims. In other words, if an employee makes a workers’ compensation claim, he or she may not sue the employer for his or her injury. The amounts provided for medical expenses and lost wages are often lower than an employee may receive in a successful lawsuit. However, the employee benefits from receiving payment upfront and does not have to risk the uncertain outcome of a lawsuit or pay attorney fees associated with litigation.

There are two exceptions to the exclusive remedy doctrine:

- Intentional actions resulting in harm; and

- Product liability claims against a manufacturer of a defective product.

State law varies with respect to types of workers who are excluded from coverage, as well as types and amount of compensation. All states cover medical costs, rehabilitation costs, and lost wages and benefits as a result of the injury.

In general, an employee may recover workers’ compensation benefits when:

- The employer has complied with the state’s legal requirements;

- The employee was acting in the course of his or her employment when injured;

- The injury was proximately caused by his or her employment (i.e. the injury was not caused by off work activities); and

- The employee did not intentionally injure himself or herself.

An employer may not retaliate against an employee who files a workers’ compensation claim.

13.9 Unemployment Compensation

Every state provides an unemployment compensation insurance program that is funded by a tax paid by employers. To draw from the program, an employee must:

- Have worked for the employer for a certain amount of time;

- Not have quit without good cause;

- Not have been fired for egregious behavior;

- Be capable of work; and

- Actively look for a new job.

Unemployment compensation is meant to help workers who are subject to lay offs and reductions in force while they look for new employment. It is generally not available to employees who voluntarily leave a job and want to continue receiving income from their former employer.

States have different formulas for calculating unemployment compensation, but in general benefits are a percentage of past earnings and are available for a limited period of time.

13.10 Labor Relations

Labor law affects the working relationship of employees who are represented by a union in their workplace. A union is an organization formed to negotiate with employers, on behalf of workers collectively, about job-related issues such as salary, benefits, hours, and working conditions. Labor law essentially creates a framework for employers, employees, and unions to create a contract unique to that business for the purpose of regulating the employment relationship and resolving disputes.

National Labor Relations Act

The first unions in the United States were formed after the Civil War and began to flourish during the Industrial Revolution. In 1935, Congress enacted the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) to provide workers three important rights:

- The right to organize;

- The right to collectively bargain; and

- The right to strike.

The NLRA also prohibits employers and unions from engaging in unfair labor practices. Unfair labor practices by employers include:

- Interfering with protected employee rights, such as the right to self-organize;

- Discriminating against employees for union-related activities;

- Retaliating against employees who invoke their labor rights;

- Refusing to engage in collective bargaining;

- Interfering with the administration of a union; and

- Discouraging employees from forming or joining a union.

Unfair labor practices by unions include:

- Causing an employer to discriminate against an employee who is not a union member;

- Engaging in an illegal strike or boycott;

- Requiring an employer to hire more employees than necessary (called featherbedding);

- Coordinating a secondary boycott (an action against a third party who deals with the employer but has no direct contact with the union);

- Refusing to engage in collective bargaining; and

- Charging excessive dues.

Most states also have laws that make it illegal for an employer to mandate union membership as a condition of employment.

The NLRA also states that supervisors are not employees and do not have a right to join a union. Supervisors are individuals with the authority to make independent decisions on hiring, firing, disciplining, or promoting other employees.

Under the NLRA, a validly recognized union is the exclusive representative of the employees. This means that the union represents all the employees, even if a particular worker is not a member of the union or has not paid dues. The employer may not bargain directly either with employees or with another organization representing the employees.

Unions have a duty of fair representation, which requires unions to treat all members fairly, impartially, and in good faith. A union may not favor some members over others and may not discriminate against members based on their membership in a protected class, such as race or gender.

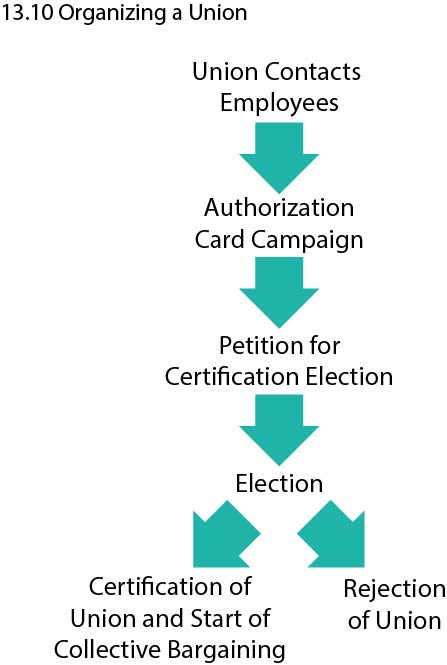

Organizing a Union

A union trying to represent employees follows these steps:

| 1. | Campaign | Union organizers try to persuade employees to form a union. An employer may not restrict organizing discussions unless they interfere with business operations. An employer may present anti-union views but may not use threats or rewards to defeat a union drive. |

| 2. | Authorization Cards | Union organizers ask employees to sign authorization cards stating that they want the union to represent them. |

| 3. | Petition | If a union obtains authorization cards from 30% of the workforce, it may petition the NLRB for an election. |

| 4. | Election | If more than 50% of the employees vote for the union, the NLRB designates it as the exclusive representative of the employees. |

Figure 13.8 Process of Union Organizing

Collective Bargaining

Once a union is formed, the employer and union must negotiate to create a new employment contract that regulates employment conditions called a collective bargaining agreement (CBA). The bargaining unit is a group of employees authorized to engage in collective bargaining on behalf of all of the employees of a company or an industry sector.

The NLRA allows the parties to bargain almost any subject they wish but it requires them to bargain wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment. Conditions of employment include:

- Benefits;

- Retirement benefits;

- Order of layoffs and recalls;

- Production quotas;

- Work rules, such as safety practices; and

- Onsite food service and prices.

The parties are not required to reach an agreement but they are required to bargain in good faith. In other words, they must meet with open minds and make a reasonable effort to reach a contract.

Concerted Activity

Concerted activity is an action by employees concerning wages or working conditions. It is action taken by members of a union to gain a bargaining advantage. Concerted activity is protected by the NLRA and cannot be used as a basis for disciplining or discharging an employee.

The most common forms of concerted activity are strikes and picketing. A strike is an organized cessation or slowdown of work by employees to compel the employer to meet the employees’ demands. The NLRA protects the employees’ right to strike when:

- The parties are unable to reach a CBA;

- The employer engages in an unfair labor practice; or

- The employer is considering sending work elsewhere.

However, a strike is illegal when:

- The union does not provide the employer with sixty days notice (when issue is modifying or terminating a CBA);

- The union represents public employees;

- The union engages in a sit-down strike, in which employees stop working but physically block replacement workers from taking their places; and

- The union engages in partial strikes, in which employees strike intermittently to disrupt operations but prevent the employer from hiring replacement workers.

When unions go on strike, employers have the right to hire replacement workers to keep the business operating. If the union engages in an economic strike to obtain increased wages and benefits, the employer may hire permanent replacement workers. When an economic strike ends, the employer is under no obligation to lay off replacement workers to allow strikers to return to work. However, if and when the employer hires additional employees, it may not discriminate against the employees who went on strike. If the union engages in an unfair labor practices strike to protest an employer’s unfair labor practice, union members are entitled to their jobs after the strike ends.

Picketing is the demonstration by one or more employees outside a business to protest its activities or policies and to pressure it to meet the protesters’ demands. The power of picketing is to publicize a labor dispute and influence the public to withhold business from the employer. Picketing is usually lawful, as long as the picketers do not prevent other employees, replacement workers, or customers from entering the business.

Employers have their own form of legal pressure on union members called a lockout. A lockout occurs when an employer closes a business or prevents workers from entering the premises and earning their paychecks because of a labor dispute. By withholding work and wages, the employer tries to pressure the union to bargain less aggressively. Most lockouts are legal.

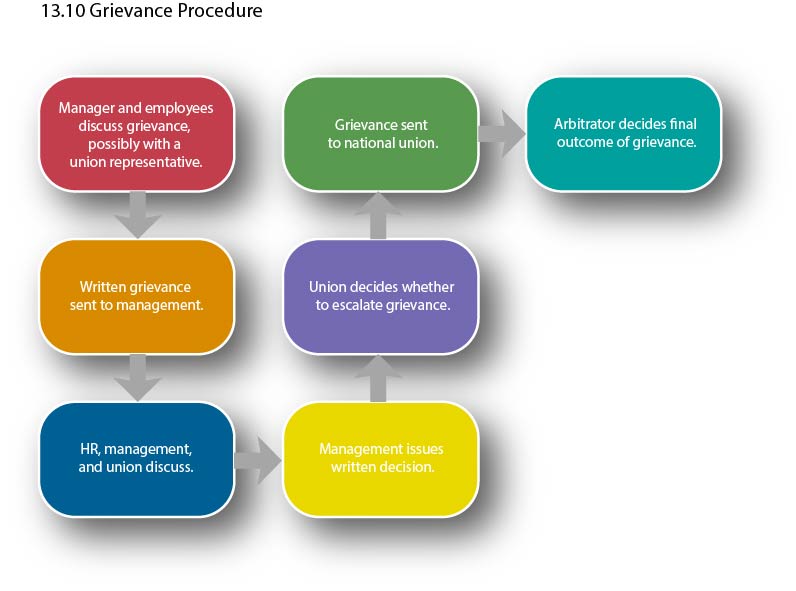

Grievance Procedure

One of the main benefits to union members is that they are able to participate in a grievance procedure when issues at work exist. A grievance is a formal employee complaint about a violation of a workplace policy or the collective bargaining agreement between the union and employer.

Figure 13.9 Grievance Procedure

The grievance procedure defines the rules and process for documenting, presenting, and resolving workplace disputes. The exact steps are usually defined in the collective bargaining agreement. However, most grievance procedures start with a discussion between the employee and his or her manager, often with a union representative present. Issues often are resolved informally at this step.

If the issue is not resolved, then the employee may write a formal grievance, which is then sent to management. After receiving a written grievance, management of the company investigates and discusses how to address the issues contained in the grievance. This process often involves the human resource department, union representatives, and consultation with legal counsel.

Management will then issue a written decision. If the union is not satisfied with the company’s response, it may decide to refer the grievance to the national union. If the national union decides to pursue the issue further, then arbitration before the NLRB or a private arbitrator often occurs.

13.11 Concluding Thoughts

Employment and labor laws regulate the employer-employee relationship. Although most laws are written to provide rights to employees, the laws try to balance the need of employers to run a profitable business with the right of employees to fair treatment. While the law does not always strike the right balance, it is helpful to understand that employers retain a lot of control in their day-to-day business operations and in establishing the business culture.