40 5.2 Chemical Weathering — Physical Geology – 2nd Edition

5.2 Chemical Weathering

Chemical weathering results from chemical changes to minerals that become unstable when they are exposed to surface conditions. The kinds of changes that take place are highly specific to the mineral and the environmental conditions. Some minerals, like quartz, are virtually unaffected by chemical weathering, while others, like feldspar, are easily altered. In general, the degree of chemical weathering is greatest in warm and wet climates, and least in cold and dry climates. The important characteristics of surface conditions that lead to chemical weathering are the presence of water (in the air and on the ground surface), the abundance of oxygen, and the presence of carbon dioxide, which produces weak carbonic acid when combined with water. That process, which is fundamental to most chemical weathering, can be shown as follows:

| H2O + CO2 ↔ H2CO3 then H2CO3 ↔ H+ + HCO3−

water + carbon dioxide ↔ carbonic acid then carbonic acid ↔ dissolved hydrogen ions + dissolved bicarbonate ions |

Yikes! Chemical formulas

Lots of people seize up when they are asked to read chemical or mathematical formulas. It’s OK, you don’t necessarily have to! If you don’t like the formulas just read the text underneath them. In time you may get used to reading the formulas.

The double-ended arrow “↔ ” indicates that the reaction can go either way, but for our purposes these reactions are going towards the right.

Here we have water (e.g., as rain) plus carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, combining to create carbonic acid. Then carbonic acid dissociates (comes apart) to form hydrogen and bicarbonate ions. The amount of CO2 in the air is enough to make weak carbonic acid. There is typically much more CO2 in the soil, so water that percolates through the soil can become more acidic. In either case, this acidic water is a critical to chemical weathering.

In some types of chemical weathering the original mineral becomes altered to a different mineral. For example, feldspar is altered—by —to form plus some ions in solution. In other cases the minerals dissolve completely, and their components go into solution. For example, calcite (CaCO3) is soluble in acidic solutions.

The hydrolysis of feldspar can be written like this:

| CaAl2Si2O8 + H2CO3 + ½O2 ↔ Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + Ca2+ + CO32−

plagioclase feldspar + carbonic acid ↔ kaolinite + dissolved calcium ions + dissolved carbonate ions |

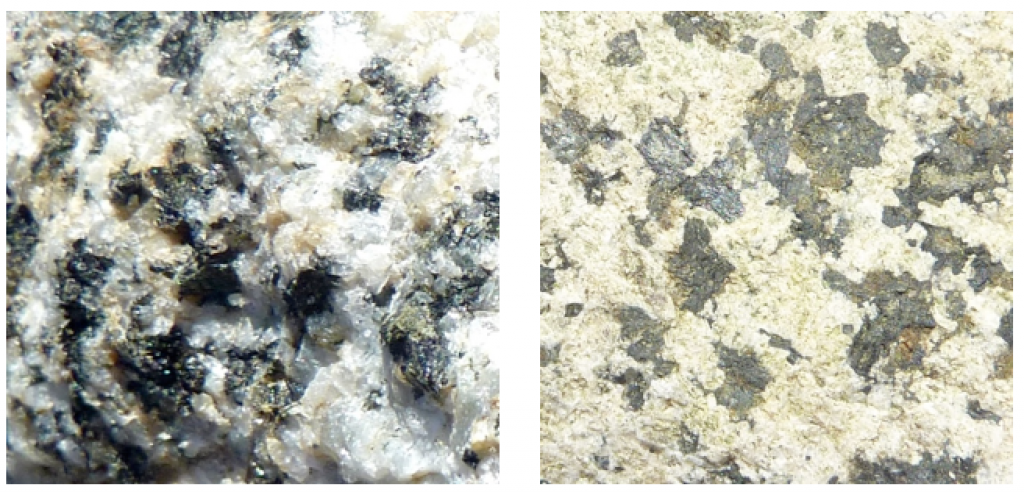

This reaction shows calcium-bearing plagioclase feldspar, but similar reactions could also be written for sodium or potassium feldspars. In this case, we end up with the mineral kaolinite, along with calcium and carbonate ions in solution. Those ions can eventually combine (probably in the ocean) to form the mineral calcite. The hydrolysis of feldspar to clay is illustrated in Figure 5.2.1, which shows two images of the same granitic rock, a recently broken fresh surface on the left and a clay-altered weathered surface on the right. Other silicate minerals can also go through hydrolysis, although the end results will be a little different. For example, pyroxene can be converted to the clay minerals chlorite or smectite, and olivine can be converted to the clay mineral serpentine.

Oxidation is another very important chemical weathering process. The oxidation of the iron in a ferromagnesian silicate starts with the dissolution of the iron. For olivine, the process looks like this, where olivine in the presence of carbonic acid is converted to dissolved iron, carbonate, and silicic acid:

But in the presence of oxygen and carbonic acid, the dissolved iron is then quickly converted to the mineral hematite:

|