28 3.5 Intrusive Igneous Bodies — Physical Geology – 2nd Edition

3.5 Intrusive Igneous Bodies

In most cases, a body of hot magma is less dense than the rock surrounding it, so it has a tendency to move very slowly up toward the surface. It does so in a few different ways, including filling and widening existing cracks, melting the surrounding rock (called [1]), pushing the rock aside (where it is somewhat plastic), and breaking the rock. Where some of the country rock is broken off, it may fall into the magma, a process called stoping. The resulting fragments, illustrated in Figure 3.5.1, are known as xenoliths (Greek for “strange rocks”).

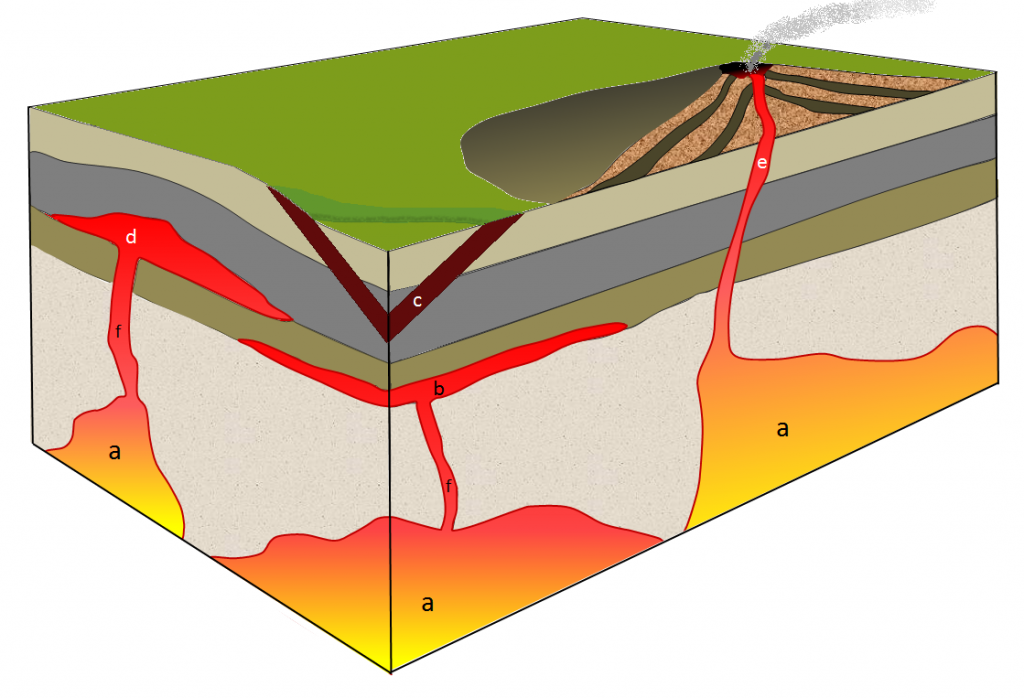

Some upward-moving magma reaches the surface, resulting in volcanic eruptions, but most cools within the crust. The resulting body of rock is known as a pluton. Plutons can have various different shapes and relationships to the surrounding country rock as shown in Figure 3.5.2.

Large irregular-shaped plutons are called either stocks or batholiths. The distinction between the two is made on the basis of the area that is exposed at the surface: if the body has an exposed surface area greater than 100 square kilometers (km2), then it’s a batholith; smaller than 100 km2 and it’s a stock. Batholiths are typically formed only when a number of stocks coalesce beneath the surface to create one large body. A grand example of a batholith is Pikes Peak, west of Manitou Springs, CO. The entire mountain is essentially an old magma chamber (~ 1 Ga in age). that has been thrusted up by tectonic forces, and sculpted through time by weathering.

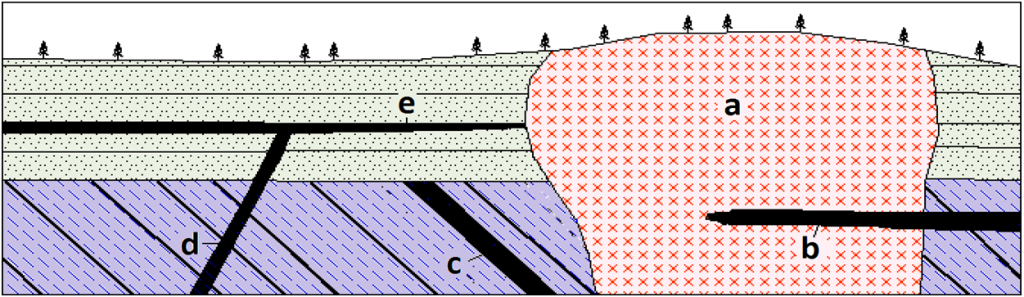

Tabular (sheet-like) plutons are distinguished on the basis of whether or not they are concordant with (i.e., parallel to) existing layering (e.g., sedimentary bedding or metamorphic foliation) in the country rock. A sill is concordant with existing layering, and a dike is discordant (Figure 3.5.3.). If the country rock has no bedding or foliation, then any tabular body within it is a dike. Note that the sill-versus-dike designation is not determined simply by the orientation of the feature. A dike can be horizontal and a sill can be vertical (if the bedding is vertical). A large dike can be seen in Figure 3.5.4.

Figure 3.5.3 A tan-colored sill composed of porphyry igneous rock, located in Eagle County, CO. Note that the sill trends parallel to the overlaying layer consisting of dark shales and sandstones.

A laccolith is a sill-like body that has expanded upward by deforming the overlying rock (Figure 3.5.5.).

Finally, a pipe is a cylindrical body (with a circular, elliptical, or even irregular cross-section) that served as a conduit for the movement of magma from one location to another. Most known pipes fed volcanoes, although pipes can also connect plutons. It is also possible for a dyke to feed a volcano.

Figure 3.5.6 shows a cross-section through part of the crust showing a variety of intrusive igneous rocks. Except for the granite (a), all of these rocks are mafic in composition. Indicate whether each of the plutons labelled a to e on the diagram below is a dike, a sill, a stock, or a batholith.

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 3.7 answers.

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.5.1.: Wikimedia Commons

- Figures 3.5.2, 3.5.6.: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 3.5.3., 3.5.4., 3.5.5.: Colorado Geological Survey, Vince Matthews

- “Country rock” is not necessarily music to a geologist’s ears. The term refers to the original “rock of the country” or region, and hence the rock into which the magma intruded to form a pluton. ↵