155 22.5 Are There Other Earths? — Physical Geology – 2nd Edition

The uncertainty about the 12 possible Earth-like worlds is related to their composition. We don’t yet know their composition; however, it is tempting to conclude that they are rocky because they are similar in size to Earth. Remember the rules of the accretion game: you can only begin to collect gas once you are a certain size, and how much matter you collect depends on how far away from the Sun you are. Given how large our gas giant and ice giant planets are compared to Earth, and how far away they are from the Sun, we would expect that a planet similar in size to Earth, and a similar distance from its star, should be rocky.

It isn’t quite as simple as that, however. We are finding that the rules to the accretion game can result in planetary systems very different from our own, leading some people to wonder whether those planetary systems are strange, or ours is, and if ours is strange, how strange is it?

Consider that in the Kepler mission’s observations thus far, it is very common to find planetary systems with planets larger than Earth orbiting closer to their star than Mercury does to the Sun. It is rare for planetary systems to have planets as large as Jupiter, and where large planets do exist, they are much closer to their star than Jupiter is to the Sun. To summarize, we need to be cautious about drawing conclusions from our own solar system, just in case we are basing those conclusions on something truly unusual.

On the other hand, the seemingly unique features of our solar system would make planetary systems like ours difficult to spot. Small planets are harder to detect because they block less of a star’s light than larger planets. Larger planets farther from a star are difficult to spot because they don’t go past the star as frequently. For example, Jupiter goes around the Sun once every 12 years, which means that if someone were observing our solar system, they might have to watch for 12 years to see Jupiter go past the Sun once. For Saturn, they might have to watch for 30 years.

So let’s say the habitable-zone exoplanets are terrestrial. Does that mean we could live there?

The operational definition of “other Earths,” which involves a terrestrial composition, a size constraint of one to two times that of Earth, and location within a star’s habitable zone, does not preclude worlds incapable of supporting life as we know it. By those criteria, Venus is an “other Earth,” albeit right on the edge of the habitable zone for our Sun. Venus is much too hot for us, with a constant surface temperature of 465°C (lead melts at 327°C). Its atmosphere is almost entirely carbon dioxide, and the atmospheric pressure at its surface is 92 times higher than on Earth. Any liquid water on its surface boiled off long ago. Yet the characteristics that make Venus a terrible picnic destination aren’t entirely things we could predict from its distance from the sun. They depend in part on the geochemical evolution of Venus, and at one time Venus might have been a lot more like a youthful Earth. These are the kinds of things we won’t know about until we can look carefully at the atmospheres and compositions of habitable-zone exoplanets.

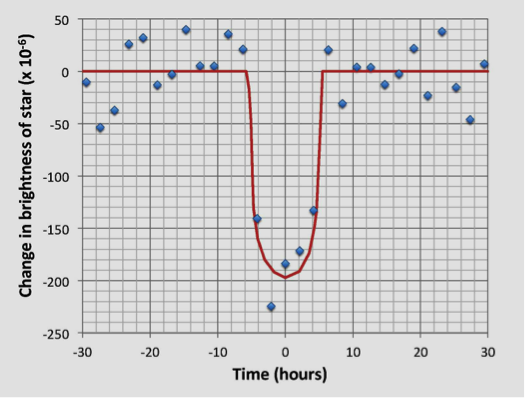

One of the techniques for finding exoplanets is to measure changes in the brightness of a host star as the planet crosses in front of it and blocks some of its light. This diagram shows how the brightness changes over time. The dip in brightness reflects a planet crossing between the star and the instrument observing the star.

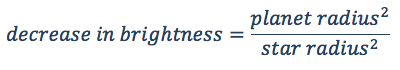

Often the planet itself is too small to see directly. If all we know is how the planet affects the brightness of the star, and we can’t even see the planet, then how do we know how big the planet is? The answer is that the two are related. We can write an equation for this relationship using the radius of the planet and the radius of the star.

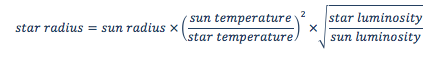

Let’s try this out for the Earth-like exoplanet called Kepler-452b. The first thing we need to know is the size of the host star Kepler-452. We can get that information by comparing its surface temperature and brightness to that of the sun. Start by calculating the ratios of the sun’s temperature to the star’s temperature, and the star’s luminosity to the sun’s luminosity using the data in Table 22.5. Record your answers in the table. Then find the star’s radius using the following equation, and record your result:

| Description | Sun | Kepler-452 | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (degrees Kelvin) | 5,778 | 5,757 | |

| Luminosity (× 1026 watts) | 3.846 | 4.615 | |

| Radius (km) | 696,300 |

The second thing we need to know is how the brightness of Kepler-452 changes as planet Kepler-452b moves in front of it. Use the plot shown in this exercise box to find this information. Find the value on the y-axis where the red curve shows the most dimming from the planet and record your result in Table 22.6.

| Decrease in brightness* | Earth radius in km | Kepler-452b radius in km | Kepler-452b radius/Earth radius |

|---|---|---|---|

| x 10−6 | 6,378 |

* Because we know this is a decrease, you don’t need to keep the negative sign.

Use the following equation to find the radius of Kepler-452b:

To put the size of Kepler-452b in perspective, divide its radius by that of Earth and record your answer.

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 22.2 answers.

Image Descriptions

Equation 2 image description: Star radius equals sun radius times begin fraction sun temperature over star temperature end fraction squared times begin square root begin fraction star luminosity over sun luminosity end fraction end square root. [Return to Equation 2]

Media Attributions

- Figure 22.5.1: © Karla Panchuk. CC BY. Based on data from Jenkins, J. et al, 2015, Discovery and validation of Kepler-452b: a 1.6REarth super Earth exoplanet in the habitable zone of a G2 star, Astronomical Journal, V 150, DOI 10.1088/0004-6256/150/2/56.

<!– pb_fixme –>

<!– pb_fixme –>