138 20.1 Metal Deposits — Physical Geology – 2nd Edition

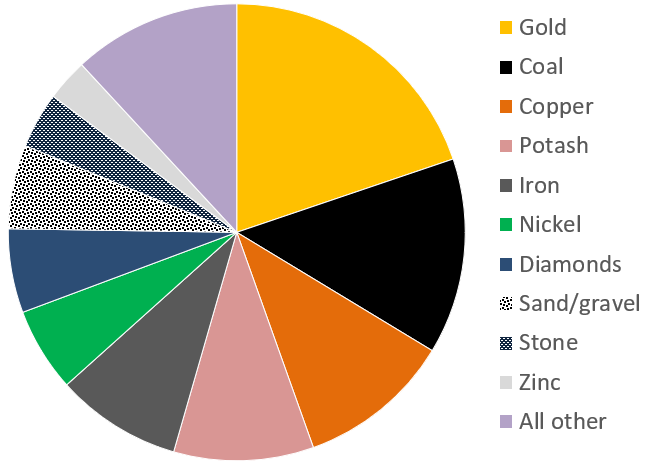

Canada’s mining sector had revenues in the order of $44 billion in 2017 (Figure 20.1.1). The 4 most valuable commodities were gold, coal, copper and potash, with important amounts from iron, nickel, diamonds, sand and gravel aggregates, stone and zinc. Revenues from the petroleum sector are significantly higher, at over $100 billion per year.

A metal deposit is a body of rock in which one or more metals have been concentrated to the point of being economically viable for recovery. Some background levels of important metals in average rocks are shown on Table 20.1, along with the typical grades necessary to make a viable deposit, and the corresponding concentration factors. Looking at copper, for example, we can see that while average rock has around 40 ppm (parts per million) of copper, a grade of around 10,000 ppm or 1% is necessary to make a viable copper deposit. In other words, copper ore has about 250 times as much copper as typical rock. For the other elements in the list, the concentration factors are much higher. For gold, it’s 2,000 times and for silver it’s around 10,000 times.

| Metal | Typical Background Level | Typical Economic Grade* | Concentration Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 40 ppm | 10,000 ppm (1%) | 250 times |

| Gold | 0.003 ppm | 6 ppm (0.006%) | 2,000 times |

| Lead | 10 ppm | 50,000 ppm (5%) | 5,000 times |

| Molybdenum | 1 ppm | 1,000 ppm (0.1%) | 1,000 times |

| Nickel | 25 ppm | 20,000 ppm (2%) | 800 times |

| Silver | 0.1 ppm | 1,000 ppm (0.1%) | 10,000 times |

| Uranium | 2 ppm | 10,000 ppm (1%) | 5,000 times |

| Zinc | 50 ppm | 50,000 ppm (5%) | 1,000 times |

| *It’s important to note that the economic viability of any deposit depends on a wide range of factors including its grade, size, shape, depth below the surface, and proximity to infrastructure, the current price of the metal, the labour and environmental regulations in the area, and many other factors. | |||

It is clear that some very significant concentration must take place to form a mineable deposit. This concentration may occur during the formation of the host rock, or after the rock forms, through a number of different types of processes. There is a very wide variety of ore-forming processes, and there are hundreds of types of mineral deposits. The origins of a few of them are described below.

Magmatic Nickel Deposits

A magmatic deposit is one in which the metal concentration takes place primarily at the same time as the formation and emplacement of the magma. Most of the nickel mined in Canada comes from magmatic deposits such as those in Sudbury (Ontario), Thompson (Manitoba) (Figure 20.1.2), and Voisey’s Bay (Labrador). The magmas from which these deposits form are of mafic or ultramafic composition (derived from the mantle), and therefore they had relatively high nickel and copper contents to begin with (as much as 100 times more than normal rocks in the case of nickel). These elements may be further concentrated within the magma as a result of the addition of sulphur from partial melting of the surrounding rocks. The heavy nickel and copper sulphide minerals are then concentrated further still by gravity segregation (i.e., crystals settling toward the bottom of the magma chamber). In some cases, there are also significant concentrations of platinum-bearing minerals in magmatic deposits.

Most of these types of deposits around the world are Precambrian in age; the mantle was significantly hotter at that time, and the necessary mafic and ultramafic magmas were more likely to be emplaced in the continental crust.

Volcanogenic Massive Sulphide Deposits

Much of the copper, zinc, lead, silver, and gold mined in Canada is mined from volcanic-hosted massive sulphide (VHMS) deposits associated with submarine volcanism (VMS deposits). Examples are the deposits at Kidd Creek, Ontario, Flin Flon on the Manitoba-Saskatchewan border, Britannia on Howe Sound, and Myra Falls (within Strathcona Park) on Vancouver Island.

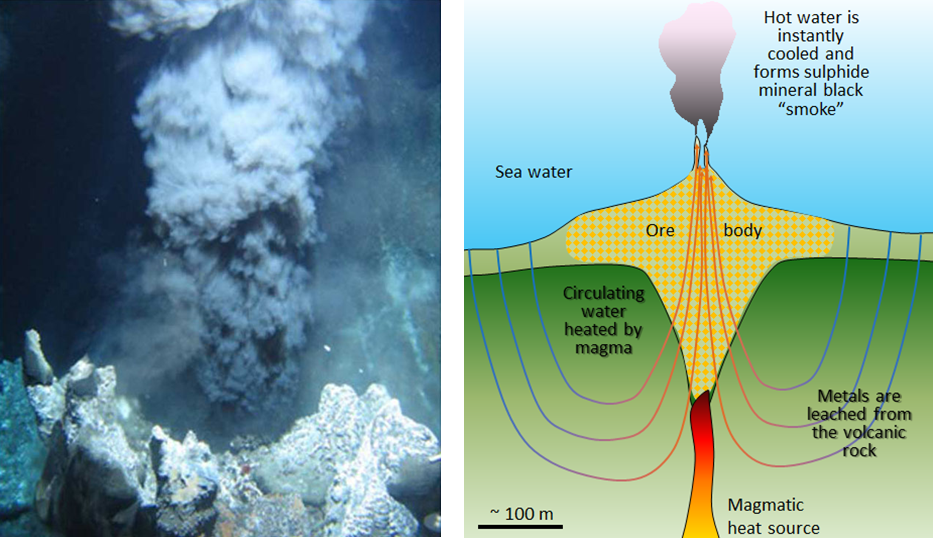

VMS deposits are formed from the water discharged at high temperature (250° to 300°C) at ocean-floor hydrothermal vents, primarily in areas of subduction-zone volcanism. The environment is comparable to that of modern-day black smokers (Figure 20.1.3), which form where hot metal- and sulphide-rich water issues from the sea floor. They are called massive sulphide deposits because the sulphide minerals (including pyrite (FeS2) , sphalerite (ZnS), chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), and galena (PbS)) are generally present in very high concentrations (making up the majority of the rock in some cases). The metals and the sulphur are leached out of the sea-floor rocks by convecting groundwater driven by the volcanic heat, and then quickly precipitated where that hot water enters the cold seawater, causing it to cool suddenly and change chemically. The volcanic rock that hosts the deposits is formed in the same area and at the same general time as the accumulation of the ore minerals.

Porphyry Deposits

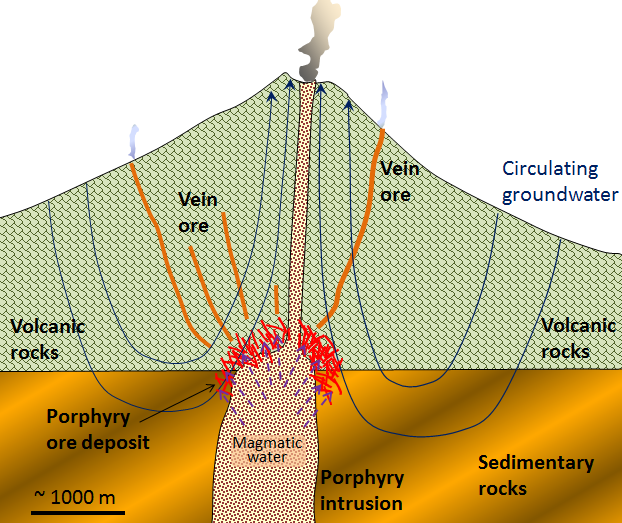

Porphyry deposits are the most important source of copper and molybdenum in British Columbia, the western United States, and Central and South America. Most porphyry deposits also host some gold, and in rare cases gold is the primary commodity. B.C. examples include several large deposits within the Highland Valley mine (Figure 20.0.1) and numerous other deposits scattered around the central part of the province.

A porphyry deposit forms around a cooling felsic stock in the upper part of the crust. They are called “porphyry” because upper crustal stocks are typically porphyritic in texture, the result of a two-stage cooling process. Metal enrichment results in part from convection of groundwater related to the heat of the stock, and also from metal-rich hot water expelled by the cooling magma (Figure 20.1.4). The host rocks, which commonly include the stock itself and the surrounding country rocks, are normally highly fractured and brecciated. During the ore-forming process, some of the original minerals in these rocks are altered to potassium feldspar, biotite, epidote, and various clay minerals. The important ore minerals include chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), bornite (Cu5FeS4), and pyrite in copper porphyry deposits, or molybdenite (MoS2) and pyrite in molybdenum porphyry deposits. Gold is present as minute flakes of native gold.

This type of environment (i.e., around and above an intrusive body) is also favourable for the formation of other types of deposits—particularly vein-type gold deposits (a.k.a. epithermal deposits). Some of the gold deposits of British Columbia (such as in the Eskay Creek area adjacent to the Alaska panhandle), and many of the other gold deposits situated along the western edge of both South and North America are of the vein type shown in Figure 20.1.4, and are related to nearby magma bodies.

Banded Iron Formation

Most of the world’s major iron deposits are of the banded iron formation type, and most of these formed during the initial oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere between 2,400 and 1,800 Ma. At that time, iron that was present in dissolved form in the ocean (as Fe2+) became oxidized to its insoluble form (Fe3+) and accumulated on the sea floor, mostly as hematite interbedded with chert (Figure 20.1.5). Unlike many other metals, which are economically viable at grades of around 1% or even much less, iron deposits are only viable if the grades are in the order of 50% iron and if they are very large.

Unconformity-Type Uranium Deposits

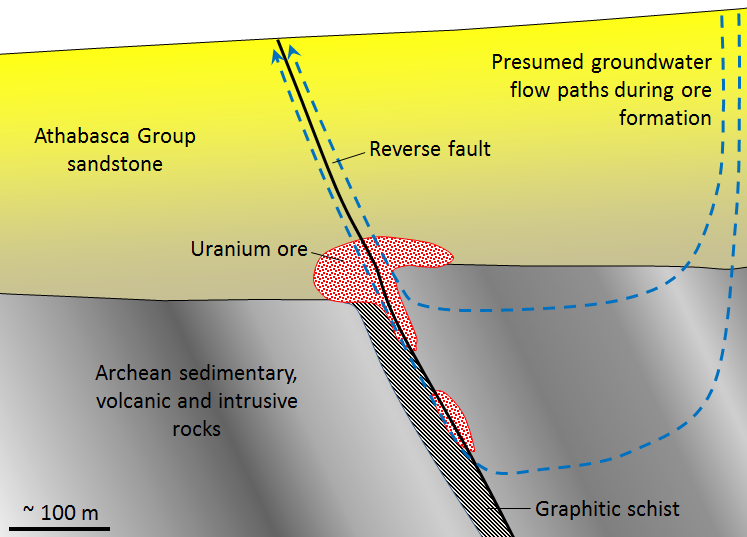

There are several different types of uranium deposits, but some of the largest and richest are those within the Athabasca Basin of northern Saskatchewan. These are called unconformity-type uranium deposits because they are all situated very close to the unconformity between the Proterozoic Athabasca Group sandstone and the much older Archean sedimentary, volcanic, and intrusive igneous rock (Figure 20.1.6). The origin of unconformity-type U deposits is not perfectly understood, but it is thought that two particular features are important: (1) the relative permeability of the Athabasca Group sandstone, and (2) the presence of graphitic schist within the underlying Archean rocks. The permeability of the sandstone allowed groundwater to flow through it and leach out small amounts of U, which stayed in solution in the oxidized form U6+. The graphite (C) created a reducing (non-oxidizing) environment that converted the uranium from U6+ to insoluble U4+, at which point it was precipitated as the mineral uraninite (UO2).

For a variety of reasons, thermal energy (heat) from within Earth is critical in the formation of many types of ore deposits. Look back through the deposit-type descriptions above and complete the following table, describing which of those deposit types depend on a source of heat for their formation, and why.

| Deposit Type | Is heat a factor? | If so, what is the role of the heat? |

|---|---|---|

| Magmatic | ||

| Volcanogenic massive sulphide | ||

| Porphyry | ||

| Banded iron formation | ||

| Unconformity-type uranium |

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 20.2 answers.

Mining and Mineral Processing

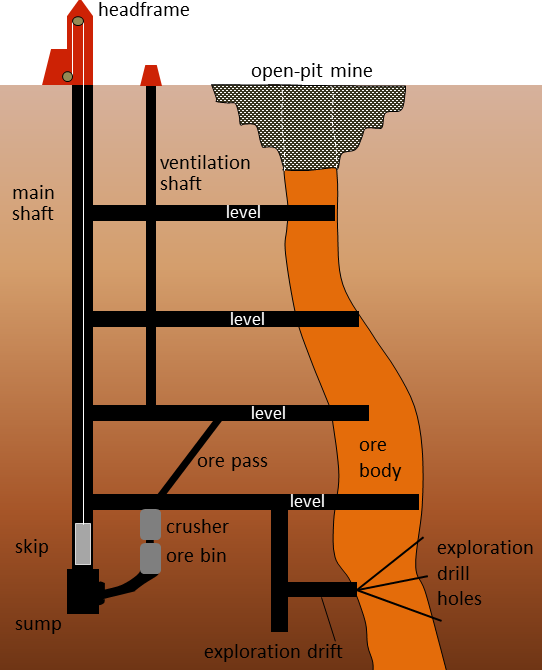

Metal deposits are mined in a variety of different ways depending on their depth, shape, size, and grade. Relatively large deposits that are quite close to the surface and somewhat regular in shape are mined using open-pit mine methods (Figure 20.0.1). Creating a giant hole in the ground is generally cheaper than making an underground mine, but it is also less precise, so it is necessary to mine a lot of waste rock along with the ore. Relatively deep deposits or those with elongated or irregular shapes are typically mined from underground with deep vertical shafts, declines (sloped tunnels), and levels (horizontal tunnels) (Figures 20.1.7 and 20.1.9). In this way, it is possible to focus the mining on the ore body itself. However, with relatively large ore bodies, it may be necessary to leave some pillars to hold up the roof.

In many cases, the near-surface part of an ore body is mined with an open pit, while the deeper parts are mined underground (Figures 20.1.8 and 20.1.9).

A typical metal deposit might contain a few percent of ore minerals (e.g., chalcopyrite or sphalerite), mixed with the minerals of the original rock (e.g., quartz or feldspar). Other sulphide minerals are commonly present within the ore, especially pyrite.

When ore is processed (typically very close to the mine), it is ground to a fine powder and the ore minerals are physically separated from the rest of the rock to make a concentrate. At a molybdenum mine, for example, this concentrate may be almost pure molybdenite (MoS2). The rest of the rock is known as tailings. It comes out of the concentrator as a wet slurry and must be stored near the mine, in most cases, in a tailings pond.

The tailings pond at the Myra Falls Mine on Vancouver Island and the settling ponds for waste water from the concentrator are shown in Figure 20.1.10. The tailings are contained by an embankment. Also visible in the foreground is a pile of waste rock, which is non-ore rock that was mined in order to access the ore. Although this waste rock contains little or no ore minerals, at many mines it contains up to a few percent pyrite. The tailings and the waste rock at most mines are an environmental liability because they contain pyrite plus small amounts of ore minerals. When pyrite is exposed to oxygen and water, it generates sulphuric acid—also known as acid rock drainage (ARD). Acidity itself is a problem to the environment, but because the ore elements, such as copper or lead, are more soluble in acidic water than neutral water, ARD is also typically quite rich in metals, many of which are toxic.

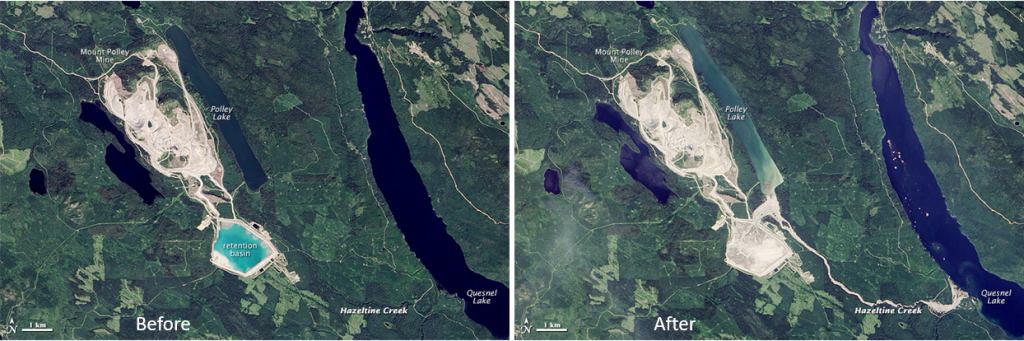

Tailings ponds and waste-rock storage piles must be carefully maintained to ensure their integrity and monitored to ensure that acidic and metal-rich water is not leaking out. In August 2014, the tailings pond at the Mt. Polley Mine in central B.C. failed and 10 million cubic metres of waste water along with 4.5 million cubic metres of tailings slurry was released into Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek, and Quesnel Lake (Figure 20.1.11, a and b). As of 2019, the environmental implications of this event are still not fully understood.

Most mines have concentrators on site because it is relatively simple to separate ore minerals from non-ore minerals and this significantly reduces the costs and other implications of transportation. But separation of ore minerals is only the preliminary stage of metal refinement, for most metals the second stage involves separating the actual elements within the ore minerals. For example, the most common ore of copper is chalcopyrite (CuFeS2). The copper needs to be separated from the iron and sulphur to make copper metal and that involves complicated and very energy-intensive processes that are done at smelters or other types of refineries. Because of their cost and the economies of scale, there are far fewer refineries than there are mines.

There are several metal refineries (including smelters) in Canada; some examples are the aluminum refinery in Kitimat, B.C. (which uses ore from overseas); the lead-zinc smelter in Trail, B.C.; the nickel smelter at Thompson, Manitoba; numerous steel smelters in Ontario, along with several other refining operations for nickel, copper, zinc, and uranium; aluminum refineries in Quebec; and a lead smelter in New Brunswick.

Image Descriptions

| Mining Sector | Value (in billions) |

|---|---|

| Total value | $36.7 |

| Potash | $6.1 |

| Gold | $5.9 |

| Iron | $5.3 |

| Copper | $4.6 |

| Nickel | $3.5 |

| Diamonds | $2.0 |

| Sand and gravel | $1.7 |

| Cement | $1.6 |

| Stone | $1.5 |

| Zinc | $0.8 |

| Uranium | $0.7 |

| Salt | $0.6 |

| Other metals | $2.4 |

Figure 20.1.8 image description: An open-pit mine is dug to access the ore that is near the surface. For ore farther down, an underground mine will be constructed to access the ore. This diagram shows the main shaft (a large vertical tunnel) with four levels (horizontal tunnels) connected to it. The levels run from the main shaft into the ore body. A ventilation shaft runs up through the four levels in between the main shaft and the ore for air circulation.

Media Attributions

- Figure 20.1.1: © Steven Earle. CC BY. Based on data from Natural Resources Canada.

- Figure 20.1.2: “Vale Nickel Mine” © Timkal. CC BY-SA.

- Figure 20.1.3 (left): “Black Smoker” by D. Butterfield, Univ. of Washington and J. Holden, Univ. Massachusetts Amherst. Public domain.

- Figure 20.1.3 (right): © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 20.1.4: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 20.1.5: “Bestand: Black-band ironstone” © Aka. CC BY-SA.

- Figures 20.1.6, 20.1.7, 20.1.8, 20.1.9, 20.1.10, 20.1.11: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 20.1.11 (left): “Mount Polley Mine site” by Visible Earth, NASA. Public domain.

- Figure 20.1.11 (right): “Mount Polley Mine site dam breach 2014” by Visible Earth, NASA. Public domain.

- Table by Steven Earle. ↵

<!– pb_fixme –>

<!– pb_fixme –>