124 17.5 Human Interference with Shorelines — Physical Geology – 2nd Edition

Seawalls, like the one around Vancouver’s Stanley Park (Figure 17.5.1), also help to limit erosion and can be very pleasant amenities for the public, but they have geological and ecological costs. When a shoreline is “hardened” in this way, important marine habitat is lost and sediment production is reduced, and that can affect beaches elsewhere. Seawalls also affect the behaviour of waves and longshore currents, sometimes with negative results.

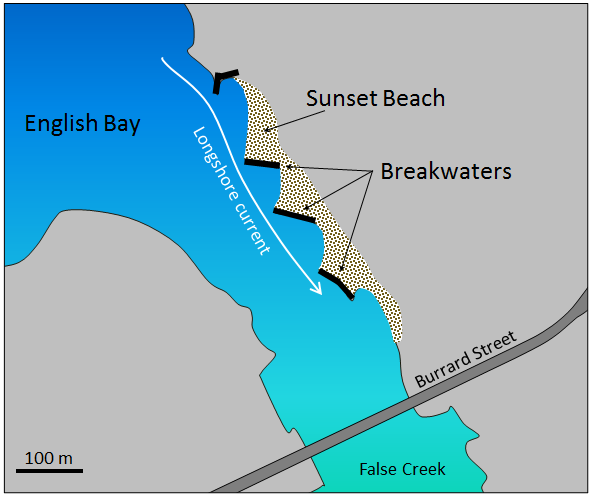

Another example is at Sunset Beach in Vancouver. As shown in Figure 17.5.2, a series of rip-rap breakwaters (structures parallel to the shore) were built in the 1990s and sand has accumulated behind them to form the beach. The breakwaters have acted as islands and the sand has been deposited in the low-energy water behind them, in the same way that a tombolo forms. This can be seen from a photograph taken from the Burrard Bridge in 2015 (Figure 17.5.3). The two benefits of this project are that a pleasant beach has been created, and some of the sediment that previously would have been moved into False Creek, and could have blocked its entrance, has been trapped in English Bay. The negative impacts are probably not well understood, but have likely involved loss of marine animal habitat.

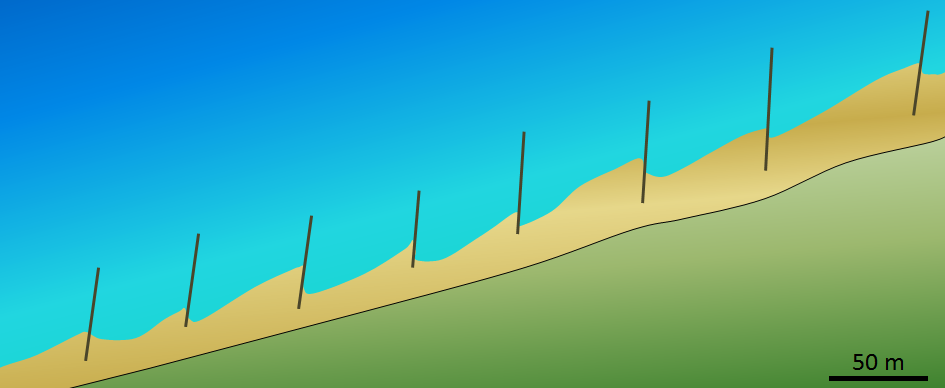

Groynes (or groins in the U.S.) have an effect that is similar to that of breakwaters, although groynes are constructed perpendicular to the beach (Figure 17.5.4), and they trap sediment by slowing the longshore current.

Most of the sediment that forms beaches along our coasts comes from rivers, so if we want to take care of beaches, we have to take care of rivers. When a river is dammed, its sediment load is deposited in the resulting reservoir, and for the century or two while the reservoir is filling up, that sediment cannot get to the sea. During that time, beaches (including spits, baymouth bars, and tombolos) within tens of kilometres of the river’s mouth (or more in some cases) are at risk of erosion.

This diagram shows the same area illustrated in Figure 17.5.4 at Crescent Beach in Surrey, B.C. Based on information that you can find on the Internet about the function of groynes, determine which way the prevailing longshore current is moving at this location.

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 17.5 answers.

Media Attributions

- Figure 17.5.1: “Seawall2” by Bonanny. Public domain.

- Figure 17.5.2: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 17.5.3: “Sunset Beach” © Isaac Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 17.5.4: “Cresbeach groyne” © Arnold C. CC BY.

- Figure 17.5.5: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

<!– pb_fixme –>

<!– pb_fixme –>