87 11.5 Forecasting Earthquakes and Minimizing Damage and Casualties — Physical Geology – 2nd Edition

11.5 Forecasting Earthquakes and Minimizing Damage and Casualties

It has long been a dream of seismologists, geologists, and public safety officials, to be able to accurately predict the location, magnitude, and timing of earthquakes on time scales that would be useful for minimizing danger to the public and damage to infrastructure (e.g., weeks, days, hours). Many different avenues of prediction have been explored, such as using observations of warning foreshocks, changes in magnetic fields, seismic tremor, changing groundwater levels, strange animal behavior, observed periodicity, stress transfer considerations, and others. So far, none of the research into earthquake prediction has provided a reliable method. Although there are some reports of successful earthquake predictions, they are rare, and many are surrounded by doubtful circumstances.

The problem with earthquake predictions, as with any other type of prediction, is that they have to be accurate most of the time, not just some of the time. We have come to rely on weather predictions because they are generally (and increasingly) accurate. But if we try to predict earthquakes and are only accurate 10% of the time (and even that isn’t possible with the current state of knowledge), the public will lose faith in the process very quickly, and then will ignore all of the predictions. Efforts are currently focused on forecasting earthquake probabilities, rather than predicting their occurrence.

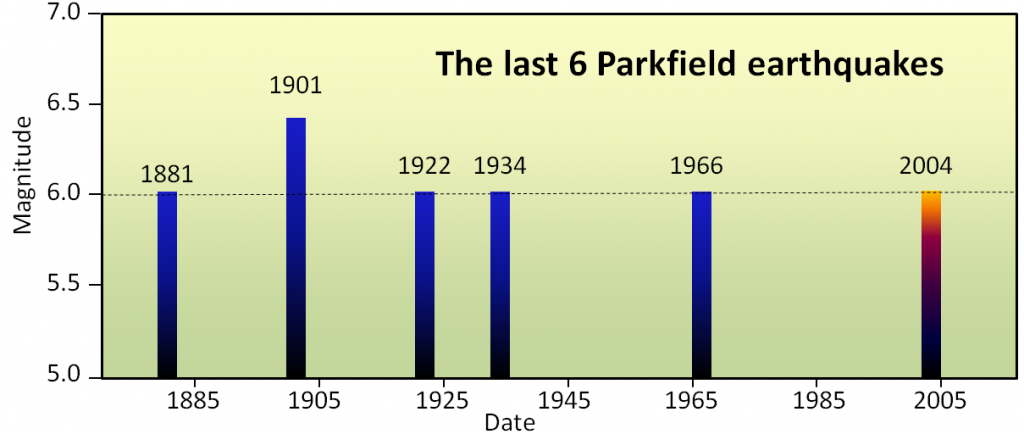

There was great hope for earthquake predictions late in the 1980s when attention was focused on part of the San Andreas Fault at Parkfield, about 200 kilometers south of San Francisco. Between 1881 and 1965 there were five earthquakes at Parkfield, most spaced at approximately 20-year intervals, all confined to the same 20 kilometer-long segment of the fault, and all very close to M6 (Figure 11.5.1). Both the 1934 and 1966 earthquakes were preceded by small foreshocks exactly 17 minutes before the main quake.

The U.S. Geological Survey recognized this as an excellent opportunity to understand earthquakes and earthquake prediction, so they armed the Parkfield area with a huge array of geophysical instruments and waited for the next quake, which was expected to happen around 1987. Nothing happened! The “1987 Parkfield earthquake” finally struck in September 2004. Fortunately all of the equipment was still there, but it was no help from the perspective of earthquake prediction. There were no significant precursors to the 2004 Parkfield earthquake in any of the parameters measured, including seismicity, harmonic tremor, strain (rock deformation), magnetic field, the conductivity of the rock, or creep, and there was no foreshock. In other words, even though every available technique was used to monitor it, the 2004 earthquake came as a complete surprise, with no warning whatsoever.

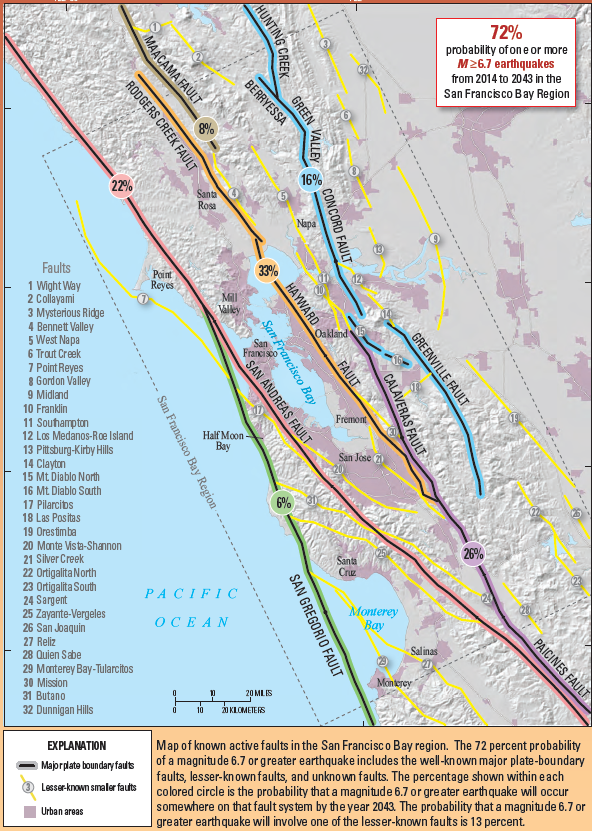

The hope for earthquake prediction is not dead, but it was hit hard by the Parkfield experiment. The current focus in earthquake-prone regions is to provide forecasts of the probability of an earthquake of a certain magnitude within a certain time period—typically a number of decades—while officials focus on ensuring that the population is educated about earthquake risks and that buildings and other infrastructure are as safe as can be. An example of this approach for the San Francisco Bay region of California is shown in Figure 11.5.2. Based on a wide range of information, including past earthquake history, accumulated stress from plate movement, and known stress transfer, seismologists and geologists have predicted the likelihood of a M6.7 or greater earthquake on each of eight major faults that cut through the region. The greatest probabilities are on the Hayward, Rogers Creek, Calaveras, and San Andreas Faults. As shown in Figure 11.5.2, there is a 72% chance that a major and damaging earthquake will take place somewhere in the region prior to 2043.

As we’ve discussed already, it’s not sufficient to have strong building codes, they have to be enforced. Building code compliance is quite robust in most developed countries, but is sadly inadequate in many developing countries.

It’s also not enough just to focus on new buildings; we have to make sure that existing buildings—especially schools and hospitals—and other structures such as bridges and dams, are as safe as they can be. An example of how this is applied to schools in B.C. is described in Exercise 11.5.

The Great Colorado ShakeOut

Under construction!

The final part of earthquake preparedness involves the formulation of public emergency plans, including escape routes, medical facilities, shelters, and food and water supplies. It also includes personal planning, such as emergency supplies (food, water, shelter, and warmth), escape routes from houses and offices, and communication strategies (with a focus on ones that don’t involve the cellular network).

Media Attributions

- Figure 11.5.1: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 11.5.2: “San Francisco Bay region Earthquake Probability [PDF]” by USGS. Public domain.

- “Seismic Mitigation Program Progress Report, July 2019.” Accessed July 21, 2019 from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/education-training/k-12/administration/capital/seismic-mitigation ↵