2 Understanding Gender: Definitions and Dimensions

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between the biological markers of sex and the social constructs of gender.

- Evaluate the role of structural binary normativity in shaping societal expectations, specifically focusing on how assigning sex at birth based solely on external genitalia ignores the complexities of internal organs, chromosomes, and future gender identity.

- Analyze the three dimensions of gender—body, identity, and social gender—to explain how their interaction produces either gender congruence or gender dysphoria.

Sex and Gender: Moving Beyond the Binary

The study of communication must begin with a foundational understanding of the distinction between sex and gender, as these terms are often incorrectly used interchangeably. For most of history, society has assumed that sex and gender conform to a strict gender binary: the belief that gender is composed of two distinct and opposite categories, boy/man and girl/woman, with no overlap. Science, however, confirms that this assumption is not biologically or medically correct, as both sex and gender exist along a spectrum or continuum. Sex is generally understood as labeling a person (e.g., male or female) at birth based on biological differences, primarily external genitalia and internal reproductive organs, though there are at least 10 recognized medically accurate markers. Gender, by contrast, is a broader, socially and culturally constructed term that encompasses a person’s lived reality. It refers to the gender identity (the deeply held, internal sense of self) and the social gender (the roles, behaviors, and expectations assigned by society). While connected, sex and gender are distinct aspects of self.

Neither Sex Nor Gender Is Binary

The prevailing idea in Western culture is the gender binary (also called gender binarism or genderism): the belief that sex and gender are composed of two distinct and opposite categories (female/male) with no overlap. This traditional viewpoint, however, is not considered scientifically or medically correct. Today, scientific fields such as genetics, biology, and neuroscience confirm that both sex and gender exist as a spectrum or continuum.

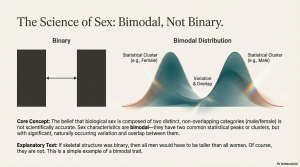

Scientific evidence demonstrates that while sex characteristics tend to be bimodal, they are not strictly binary:

- Bimodal refers to the presence of two statistical modes or clusters of characteristics often associated with “male” or “female”. However, bimodality mathematically defines a continuous probability distribution with clear overlaps between those clusters, confirming that sex exists along a spectrum.

- If sex were truly a binary (two separate, non-overlapping groups), characteristics like skeletal structure would necessitate that all men be taller than all women, which is demonstrably false.

The complexity of sex is evident across numerous biological markers:

- External Genitalia: Genitals present along a spectrum (e.g., full-size penis, small penis, micro-penis, clitoromegaly/Pseudopenis, enlarged clitoris, and standard-sized clitoris), and thus the assignment of sex at birth based only on these characteristics is highly inaccurate.

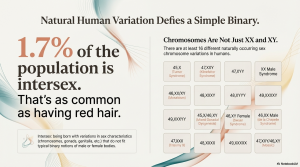

- Chromosomes: While XX and XY are the most common, sex chromosomes are diverse, with at least 16 different naturally occurring variations, such as 47, XXY (Klinefelter syndrome) or XX Male Syndrome. At least 12 chromosomes and at least 30 genes are involved in governing sex differentiation.

Intersexuality and the Challenge of Forced Binary Designation

The existence of intersex individuals fundamentally disproves the notion that sex is binary. Intersex people are born with variations in their sex characteristics, including internal and external genitalia, gonads, hormones, chromosomes, and brain structure. This level of natural variation is estimated to occur in approximately 1.7% of the population, making it about as common as having red hair.

Despite this biological reality, medical and institutional structures often force a binary categorization upon individuals, creating pervasive challenges:

- Inaccurate Assignment: Sex is typically assigned at birth based solely on external genitalia. This process is scientifically incomplete and inaccurate because it ignores other fundamental factors such as internal genitalia, chromosomes, gene expression, and how the child will eventually express their identity.

- Structural Barriers: Society’s reliance on designating only two sexes at birth leads to structural binary normativity, compelling individuals to fit into “M” or “F” options on official documentation. In fact, the absence of a third option limits the ability of non-binary and gender-diverse individuals to find appropriate and accessible language to capture their identities.

- Social Expectations: Presuming a child’s gender based on sex assigned at birth places children in “strict boxes” by conveying stereotypes about how they should look and behave.

This societal compulsion to categorize non-conforming bodies into two rigid categories extends throughout the life course, often resulting in social intrusion and control over people whose gender expression is perceived as “uncertain”. Even in contexts like healthcare, sex designation on records can trigger inappropriate clinical recommendations, illustrating the complexity of aligning gender identity with rigid binary systems.

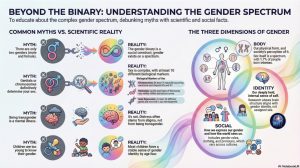

The Dimensions of Gender

Now that we have an understanding of sex as a spectrum, let’s take a look at gender and how it differs from biological sex. A person’s experience of gender is characterized by the complex interrelationship between three distinct, yet interconnected, dimensions: body, identity, and social gender.

- Body: This involves an individual’s internal experience of their own body, how society labels or “genders” bodies, and how others react to that body. The gendering of bodies occurs when society equates physical attributes with masculinity or femininity, labeling individuals as more or less of a man or woman based on the presence of these traits. For example, while humans of all genders naturally have body hair, society genders this trait by expecting women to shave their legs and armpits while encouraging men to grow beards to accentuate their “masculinity.”

- Identity (Gender Identity): This is one’s deeply held, internal sense of self as masculine, feminine, a blend, neither, or something else. This aspect is innate; individuals do not choose their gender. Gender identity can be binary (e.g., man, woman) or non-binary (e.g., genderqueer, genderfluid, agender).

- Social Gender: This is how a person presents their gender to the world (Gender Expression) and how society, culture, and community perceive, interact with, and attempt to shape that presentation. Social gender includes societal gender roles and expectations used to enforce conformity to current norms. A person may express their social gender through grooming, dress, mannerisms, us of names and pronouns, and communication styles, among other means of expression.

A person’s overall comfort and well-being regarding gender stems from gender congruence—the feeling of harmony or alignment among these three dimensions. Conversely, gender dysphoria is the distress or discomfort experienced when there is a disconnect between how one feels about their gender and how it is perceived or expressed.

Exercises

- Reflecting on the three dimensions of gender (body, identity, and social gender), can you identify a time when you felt a lack of gender congruence? How did that disconnect—whether related to how others “gendered” your body or how you were expected to express your social gender—affect your interpersonal communication?

- The sources describe how society places children in “strict boxes” by presuming gender based on sex assigned at birth. How has your own communication style been shaped by these early social expectations and the binary options (M/F) present in institutional structures?