5 The Lived Experience of Gender Diversity in Communication

The Lived Experience of Gender Diversity in Communication

Modern communication requires moving beyond the traditional gender binary to understand the unique challenges faced by transgender (TG) and non-binary (NB) individuals.

Intersectionality and Minority Stress

Intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, is a framework for understanding how multiple social categories (like gender, race, class, and sexual orientation) combine and overlap to create interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage. This lens is crucial because the challenges faced by women, for example, differ vastly depending on their race or sexual orientation.

Transgender and non-binary individuals experience high rates of minority stress—the chronic, unique stress resulting from prejudice and discrimination based on their gender identity—which significantly impacts their mental health.

- Health Disparities: TGNB adolescents report a significantly higher prevalence of depression (40.5%) and anxiety compared to cisgender peers (15.6% depression).

- Impact of Support: Crucially, TGNB youth who have supportive families and are affirmed in their gender show mental health profiles similar to their cisgender peers.

Barriers in Communication and Care

TGNB individuals face constant challenges, particularly due to pervasive cisgenderism (the assumption that everyone is cisgender and binary). These challenges manifest as two types of minority stressors in communication:

- Distal Stressors (External): These are objective instances of prejudice and discrimination.

-

- Non-Affirmation and Structural Misgendering: Misgendering (being referred to by incorrect pronouns) and deadnaming (using a previous name) are frequent microaggressions that cause psychosocial harm and distress. This non-affirmation often originates from structural sources, including electronic health records (EHR), prescription names (e.g., “male testosterone”), and gendered clinic names.

- Social Intrusiveness and Safety: TGNB individuals face heightened rates of harassment, discrimination, and bullying, leading to guardedness and fear for personal safety. Binary normativity in public places (such as restrooms, locker rooms, or changing rooms) creates a cisgenderist social need to categorize people, leading to persistent observation and social intrusiveness and control when a person’s gender expression is perceived as “uncertain”.

- Proximal Stressors (Internal): These relate to the individual’s internalized response to external stigma.

-

- The Burden of Effort: Interacting with cisgender people often requires a significant amount of effort and emotional labor, as TGNB individuals often feel compelled to educate others about gender diversity and navigate potential misunderstandings. This burden can lead to exhaustion and a sense of powerlessness.

- Fetishization and Rejection: Transgender individuals often face rejection from potential partners in dating contexts and can be subjected to fetishization—a sexual focus on “transness as an overvalued sexual object” rather than a whole person. This can lead to decreased self-esteem and the feeling of being an object or commodity.

- Avoidance of Care: The anticipation of misgendering and discrimination causes many TGNB individuals to delay or avoid seeking necessary medical care. Even hearing about others’ negative experiences can deter individuals from pursuing medical services.

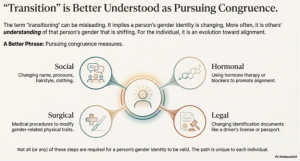

- Gender Dysphoria as a Stressor: Gender dysphoria refers to the emotional state of feeling very unhappy, uneasy, or dissatisfied in relation to one’s gender. This experience is clinically defined in the DSM-5 as the discomfort or distress connected with one’s gender incongruence or a disconnect between a person’s gender and their sex. The feelings associated with gender dysphoria can range widely from mild discomfort to unbearable distress and may occur in relation to any dimension of gender. This distress is not solely rooted in internal factors, but can be significantly triggered or increased by adverse social experiences, such as misgendering (using incorrect names or pronouns). Experiences of distress often lessen as greater congruence (harmony across the dimensions of gender) is achieved. If a person’s discomfort or distress negatively affects their quality of life and relationships, they may seek support from a trained, affirming professional. It is important to note that not all transgender and nonbinary people experience dysphoria, and cisgender people can also experience dysphoria.

Strategies for Inclusive Communication

Affirming communication and a commitment to gender literacy are crucial for overcoming these barriers and fostering positive interpersonal relationships.

- Prioritize Affirmation and Support: The support of family is the most significant factor in the mental health and well-being of a gender-expansive young person. Affirming people in their gender is essential for all and life-saving for some.

- Use Inclusive and Respectful Language: A critically important way to demonstrate support and respect is by honoring requests for chosen names and pronouns. Since language is dynamic, communicators should approach interactions with a stance of openness to the complexity of gender and the recognition that each person determines their own identity.

- Practice Empathy and Avoid Assumptions: Positive interactions are characterized by openness, honesty, and empathy, meaning cisgender individuals genuinely seek understanding. Avoid making assumptions about a person’s gender identity based on their gender expression. For instance, assuming a person’s sexual orientation based on their gender expression can be a “faulty conclusion” that hinders communication and understanding.

- Know How to Handle Mistakes (The 4 A’s): Since accidental misgendering is common, gender-affirming clinicians developed a four-step model for responding effectively when an error occurs, avoiding the potentially stigmatizing experience of placing attention on the patient’s identity. Anyone can use these steps in their personal and/or professional relationships. The steps are:

- Acknowledge: Recognize and admit the mistake internally.

- Apologize: Issue a sincere apology to the person.

- Advance: Move on from the incident immediately to avoid dwelling on it or distracting from the main reason for the interaction.

- Act: Take actionable steps to ensure the mistake does not happen again.

- Address Structural Barriers: For public institutions, effective communication requires systemic changes. This includes making healthcare, workplaces, schools, and other institutions affirming, implementing mandatory training for staff on gender-affirming practices, and providing a space for non-binary and gender-diverse employees on development and management teams.

Exercises

- Reflect on your own unique mix of social categories (such as race, gender, class, or sexual orientation). How does the framework of intersectionality help you see that two people with the same gender identity might experience vastly different communication barriers or levels of minority stress based on their other overlapping identities?

- Gender dysphoria can be triggered or increased by social experiences like misgendering, while gender congruence is fostered through affirmation. Reflect on a time when someone’s use of a specific name, pronoun, or label for you made you feel either deeply seen or deeply misunderstood; how does this illustrate the idea that affirming communication is not just about politeness, but is essential for a person’s well-being.

- Think about a time you accidentally used the wrong name or pronoun for someone. How does the “4 A’s” model (Acknowledge, Apologize, Advance, Act) provide a more effective path for repair than simply ignoring the mistake or over-apologizing? Why is the “Advance” step particularly important for preventing the other person from feeling like they have to “caretake” your emotions after your mistake?