17 Lesson 13 and 14 Managing Risk -Derivative Securities and the International Markets

Each year, American Airlines consumes approximately four billion gallons of jet fuel.1 In the spring of 2018, jet fuel prices rose from an average of $2.07 per gallon to a price of $2.19 per gallon.2 A $0.12-per-gallon increase in the price of jet fuel may not seem significant, but on an annualized basis, a price increase of this magnitude would increase the company’s jet fuel bill by approximately $500 million.

That added cost cuts into the profits of the company, leaving less money available to provide a return to the company’s investors. Rising costs could even cause the business to become unprofitable and close, causing many employees to lose their jobs. The financial managers of American Airlines are not able to control the price of jet fuel. However, they must be aware of the risk that price volatility poses to the company and consider prudent ways to manage this risk.

- American Airlines. American Airlines 2019 Environmental Data. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.americanairlines.in/content/ images/customer-service/about-us/corporate-governance/aag-2019-environmental-data.pdf

- S&P Global. “Platts Jet Fuel.” S&P Global Platts. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/oil/refined-products/ jetfuel#

- Describe risk in the context of financial management.

- Explain how risk can impact firm value.

- Distinguish between hedging and speculating.

What Is Risk?

The job of the financial manager is to maximize the value of the firm for the owners, or shareholders, of the company. The three major areas of focus for the financial manager are the size, the timing, and the riskiness of the cash flows of the company. Broadly, the financial manager should work to

- increase cash coming into the company and decrease cash going out of the company;

- speed up cash coming into the company and slow down cash going out of the company; and

- decrease the riskiness of both money coming in and money going out of the company.

The first item in this list is obvious. The more revenue a company has, the more profitable it will be. Businesspeople talk about “top line” growth when discussing this objective because revenue appears at the top of the company’s income statement. Also, the lower the company’s expenses, the more profitable the company will be. When businesspeople talk about the “bottom line,” they are focused on what will happen to a company’s net income. The net income appears at the bottom of the income statement and reflects the amount of revenue left over after all of the company’s expenses have been paid.

The second item in the list—the speed at which money enters and exits the company—has been addressed throughout this book. One of the basic principles of finance is the time value of money—the idea that a dollar received today is more valuable than a dollar received tomorrow. Many of the topics explored in this book revolve around the issue of the time value of money.

The focus of this chapter is on the third item in the list: risk. In finance, risk is defined as uncertainty. Risk occurs because you cannot predict the future. Compared to other business decisions, financial decisions are generally associated with contracts in which the parties of the contract fulfill their obligations at different points in time. If you choose to purchase a loaf of bread, you pay the baker for the bread as you receive the bread; no future obligation arises for either you or the baker because of this purchase. If you choose to buy a bond, you pay the issuer of the bond money today, and in return, the issuer promises to pay you money in the future. The value of this bond depends on the likelihood that the promise will be fulfilled.

Because financial agreements often represent promises of future payment, they entail risk. Even if the party that is promising to make a payment in the future is ethical and has every intention of honoring the promise, things can happen that can make it impossible for them to do so. Thus, much of financial management hinges on managing this risk.

Risk and Firm Value

You would expect the managers of Starbucks Corporation to know a lot about coffee. They must also know a lot about risk. It is not surprising that the term coffee appears in the text of the company’s 2020 annual report 179 times, given that the company’s core business is coffee. It might be surprising, however, that the term risk appears in the report 99 times.3 Given that the text of the annual report is less than 100 pages long, the word risk appears, on average, more than once per page.

Starbucks faces a number of different types of risk. In 2020, corporations experienced an unprecedented risk because of COVID-19. Coffee shops were forced to remain closed as communities experienced government-

- Starbucks. Starbucks Fiscal 2020 Annual Report. Seattle: Starbucks Corporation, 2020. https://s22.q4cdn.com/869488222/files/ doc_financials/2020/ar/2020-Starbucks-Annual-Report.pdf

mandated lockdowns. Locations that were able to service customers through drive-up windows were not immune to declining revenue due to the pandemic. As fewer people gathered in the workplace, Starbucks experienced a declining number of to-go orders from meeting attendees. In addition, Starbucks locations faced the risk of illness spreading as baristas gathered in their buildings to fill to-go orders.

While COVID-19 brought discussions of risk to the forefront of everyday conversations, risk was an important focus of companies such as Starbucks before the pandemic began. (The term risk appeared in the company’s 2019 annual report 82 times.4 ) Starbucks’s business model revolves around turning coffee beans into a pleasurable drink. Anything that impacts the company’s ability to procure coffee beans, produce a drink, and sell that drink to the customer will impact the company’s profitability.

The investors in the company have allowed Starbucks to use its capital to lease storefronts, purchase espresso machines, and obtain all of the assets necessary for the company to operate. Debt holders expect interest to be paid and their principal to be returned. Stockholders expect a return on their investment. Because investors are risk averse, the riskier they perceive the cash flows they will receive from the business to be, the higher the expected return they will require to let the company use their money. This required return is a cost of doing business. Thus, the riskier the cash flows of a company, the higher the cost of obtaining capital. As any cost of operating a business increases, the value of the firm declines.

LINK TO LEARNINGStarbucksThe most recent annual report for Starbucks Corp., along with the reports from recent years, is available on the company’s investor relations website under the Financial Data section (https://openstax.org/r/ Financial_Data_section). Go to the most recent annual report for the company. Search for the word risk in the annual report, and read the discussions surrounding this topic. Note the major types of risk the company discusses. Pay attention to the types of risk that Starbucks categorizes as uncontrollable and which types of risk the company attempts to mitigate.

In the following sections, you will learn about some of the types of risk that firms commonly face. You will also learn about ways in which firms can reduce their exposure to these risks. When firms take actions to reduce their exposures to risk, they are said to be hedging. Firms hedge to try to protect themselves from losses.

Thus, in finance, hedging is a risk management tool.

Certain strategies are commonly used by firms to hedge risk, which is part of corporate financial management. Many of these same strategies can be used by economic players who wish to speculate. Speculating occurs when someone bets on a future outcome. It involves trying to predict the future and profit off of that prediction, knowing that there is some risk that an incorrect prediction will lead to a loss. Speculators bet on the future direction of an asset price. Thus, speculation involves directional bets.

If you are concerned that the price of hand sanitizer is going to rise because people are concerned about a new virus and you purchase a few extra bottles to keep on your shelf “just in case,” you are hedging. If you see this situation as a business opportunity and purchase bottles of hand sanitizer, hoping that you can sell them on eBay in a few weeks at twice what you paid for them, you are speculating.

In the popular press, you will often hear of some of the strategies in this chapter discussed in terms of people using them to speculate. In upper-level finance courses, these strategies are discussed in more depth, including how they might be used to speculate. In this chapter, however, the focus is on the perspective of a financial manager using these strategies to manage risk.

- Starbucks. Starbucks Fiscal 2019 Annual Report. Seattle: Starbucks Corporation, 2019. https://s22.q4cdn.com/869488222/files/ doc_financials/2019/2019-Annual-Report.pdf

- Describe commodity price risk.

- Explain the use of long-term contracts as a hedge.

- Explain the use vertical integration as a hedge.

- Explain the use of futures contracts as a hedge.

One of the most significant risks that many companies face arises from normal business operations. Companies purchase raw materials to produce the products and provide the services they sell. A change in the market price of these raw materials can significantly impact the profitability of a company.

For example, Starbucks must purchase coffee beans in order to make its coffee drinks. The price of coffee beans is highly volatile. Sample prices of a pound of Arabica coffee beans over the past couple of decades are shown in Table 20.1. Over this period, the price of coffee beans ranged from a low of $0.52 per pound in the summer of 2002 to a high of over $3.00 per pound in the spring of 2011. The costs, and thus the profits, of Starbucks will vary greatly depending on if the company is paying less than $1.00 per pound for coffee or if it is paying three times that much.

|

Price per Pound ($) |

|

|

|

1.09 |

|

January 1, 2004 |

0.74 |

|

January 1, 2008 |

1.39 |

|

January 1, 2012 |

2.41 |

|

January 1, 2016 |

1.46 |

|

January 1, 2020 |

1.50 |

Table 20.1 Price of Coffee in Select Years, 2000-20205

Long-Term Contracts

One method of hedging the risk of volatile input prices is for a firm to enter into long-term contracts with its suppliers. Starbucks, for example, could enter into an agreement with a coffee farmer to purchase a particular quantity of coffee beans at a predetermined price over the next several years.

These long-term contracts can benefit both the buyer and the seller. The buyer is concerned that rising commodity prices will increase its cost of goods sold. The seller, however, is concerned that falling commodity prices will mean lower revenue. By entering into a long-term contract, the buyer is able to lock in a price for its raw materials and the seller is able to lock in its sales price. Thus, both parties are able to reduce uncertainty.

While long-term contracts reduce uncertainty about the commodity price, and thus reduce risk, there are several possible disadvantages to these types of contracts. First, both parties are exposed to the risk that the other party may default and fail to live up to the terms of the contract. Second, these contracts cannot be entered into anonymously; the parties to the contract know each other’s identity. This lack of anonymity may have strategic disadvantages for some firms. Third, the value of this contract cannot be easily determined, making it difficult to track gains and losses. Fourth, canceling the contract may be difficult or even impossible.

- Data from International Monetary Fund. “Global Price of Coffee, Other Mild Arabica (PCOFFOTMUSDM).” FRED. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed August 6, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCOFFOTMUSDM

Vertical Integration

A common method of handling the risk associated with volatile input prices is vertical integration, which involves the merger of a company and its supplier. For Starbucks, a vertical integration would involve Starbucks owning a coffee bean farm. If the price of coffee beans rises, the firm’s costs increase and the supplier’s revenues rise. The two companies can offset these risks by merging.

Although vertical integration can reduce commodity price risk, it is not a perfect hedge. Starbucks may decrease its commodity price risk by purchasing a coffee farm, but that action may expose it to other risks, such as land ownership and employment risk.

Futures Contracts

Another method of hedging commodity price risk is the use of a futures contract. A commodity futures contract is designed to avoid some of the disadvantages of entering into a long-term contract with a supplier. A futures contract is an agreement to trade an asset on some future date at a price locked in today. Futures exist for a range of commodities, including natural resources such as oil, natural gas, coal, silver, and gold and agricultural products such as soybeans, corn, wheat, rice, sugar, and cocoa.

Futures contracts are traded anonymously on an exchange; the market price is publicly observable, and the market is highly liquid. The company can get out of the contract at any time by selling it to a third party at the current market price.

A futures contract does not have the credit risk that a long-term contract has. Futures exchanges require traders to post margin when buying or selling commodities futures contracts. The margin, or collateral, serves as a guarantee that traders will honor their obligations. Additionally, through a procedure known as marking to market, cash flows are exchanged daily rather than only at the end of the contract. Because gains and losses are computed each day based on the change in the price of the futures contract, there is not the same risk as with a long-term contract that the counterparty to the contract will not be able to fulfill their obligation.

THINK IT THROUGHThe CME GroupIn 2007, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange merged with the Chicago Board of Trade to form CME Group Inc. CME Group provides trading in futures as well as other types of contracts that companies can use to hedge risk.You can watch the video Getting Started with Your Broker (https://openstax.org/r/ Getting_Started_with_Your_Broker) to learn how futures contracts for agricultural products such as coffee beans, corn, wheat, and soybeans are traded. You will also see other types of futures contracts traded, including futures for silver, crude oil, natural gas, Japanese yen, and Russian rubles.

20.3

20.3

Exchange Rates and Risk

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe exchange rate risk.

- Identify transaction, translation, and economic risks.

- Describe a natural hedge.

- Explain the use of forward contracts as a hedge.

- List the characteristics of an option contract.

- Describe the payoff to the holder and writer of a call option.

- Describe the payoff to the holder and writer of a put option.

The managers of companies that operate in the global marketplace face additional complications when managing the riskiness of their cash flows compared to domestic companies. Managers must be aware of differing business climates and customs and operate under multiple legal systems. Often, business must be conducted in multiple languages. Geopolitical events can impact business relationships. In addition, the company may receive cash flows and make payments in multiple currencies.

Exchange Rates

The costs to companies are impacted when the prices of the raw materials they use change. Very little coffee is grown in the United States. This means that all of those coffee beans that Starbucks uses in its espresso machines in Seattle, New York, Miami, and Houston were bought from suppliers outside of the United States. Brazil is the largest coffee-producing country, exporting about one-third of the world’s coffee.6 When a company purchases raw materials from a supplier in another country, the company needs not just money but the money that is used in that country to make the purchase. Thus, the company is concerned about the exchange rate, or the price of the foreign currency.

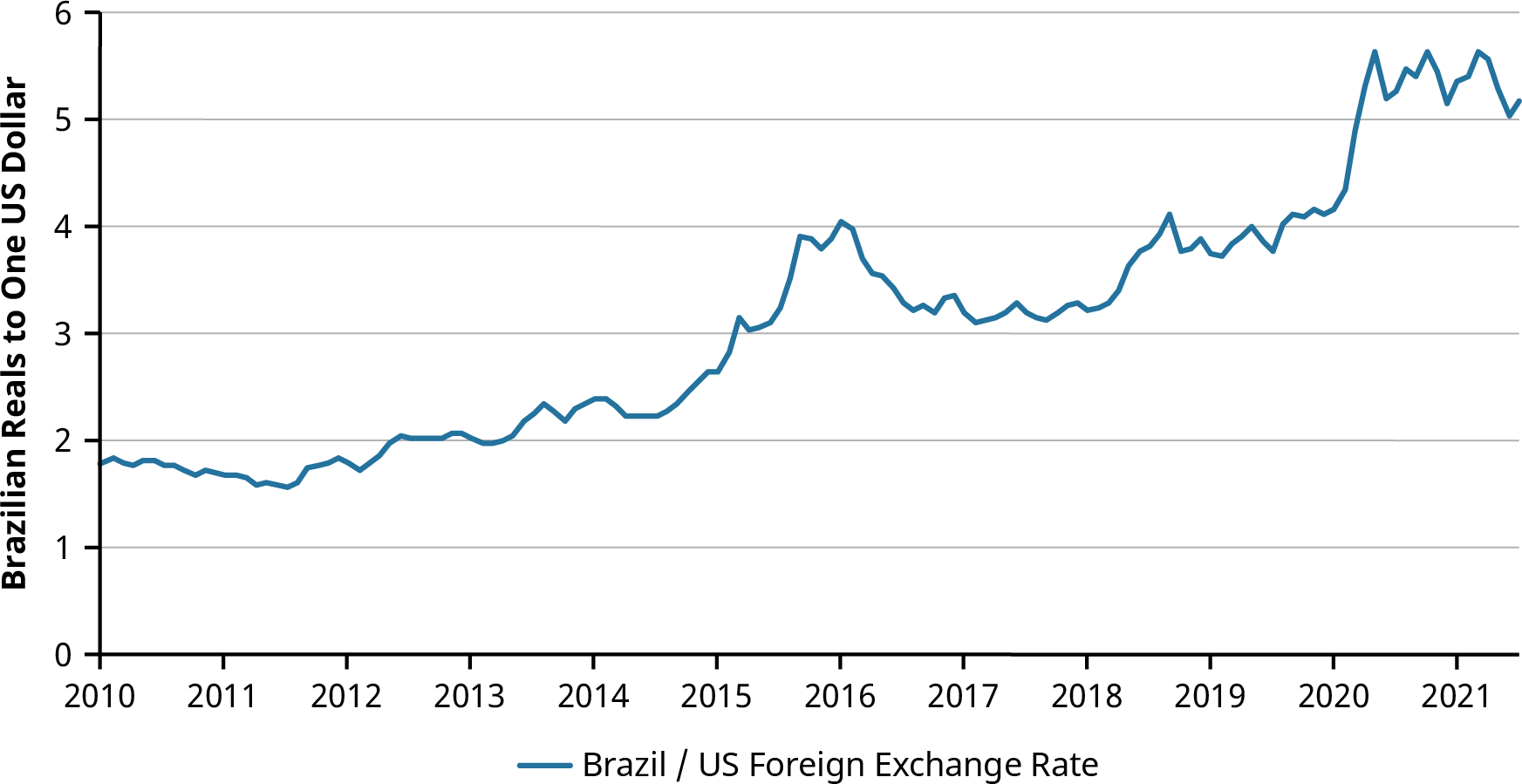

Figure 20.2 Brazilian Reals to One US Dollar7

The currency used in Brazil is called the Brazilian real. Figure 20.2 shows how many Brazilian reals could be purchased for $1.00 from 2010 through the first quarter of 2021. In March 2021, 5.4377 Brazilian reals could be purchased for $1.00. This will often be written in the form of

- Global Agricultural Information Network. Brazil: Coffee Annual 2019. GAIN Report No. BR19006. Washington, DC: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, May 2019. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/ downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Coffee%20Annual_Sao%20Paulo%20ATO_Brazil_5-16-2019.pdf

BRL is an abbreviation for Brazilian real, and USD is an abbreviation for the US dollar. This price is known as a currency exchange rate, or the rate at which you can exchange one currency for another currency.

If you know the price of $1.00 is 5.4377 Brazilian reals, you can easily find the price of Brazilian reals in US dollars. Simply divide both sides of the equation by 5.4377, or the price of the US dollar:

If you have US dollars and want to purchase Brazilian reals, it will cost you $0.1839 for each Brazilian real you want to buy.

The foreign exchange rate changes in response to demand for and supply of the currency. In early 2020, the exchange rate was. In other words, $1 purchased fewer reals in early 2020 than in it did a year later. Because you receive more reals for each dollar in 2021 than you would have a year earlier, the dollar is said to have appreciated relative to the Brazilian real. Likewise, because it takes more Brazilian reals to purchase $1.00, the real is said to have depreciated relative to the US dollar.

Exchange Rate Risks

Starbucks, like other firms that are engaged in international business, faces currency exchange rate risk. Changes in exchange rates can impact a business in several ways. These risks are often classified as transaction, translation, or economic risk.

Transaction Risk

Transaction risk is the risk that the value of a business’s expected receipts or expenses will change as a result of a change in currency exchange rates. If Starbucks agrees to pay a Brazilian coffee grower seven million Brazilian reals for an order of one million pounds of coffee beans, Starbucks will need to purchase Brazilian reals to pay the bill. How much it will cost Starbucks to purchase these Brazilian reals depends on the exchange rate at the time Starbucks makes the purchase.

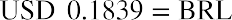

In March 2021, with an exchange rate of, it would have cost Starbucks

to purchase the reals needed to receive the one million pounds of coffee beans. If, however, Starbucks agreed in March to purchase the coffee beans several months later, in July, Starbucks would not have known then what the exchange rate would be when it came time to complete the transaction. Although Starbucks would have locked in a price of BRL 7,000,000 for one million pounds of coffee beans, it would not have known what the coffee beans would cost the company in terms of US dollars.

to purchase the reals needed to receive the one million pounds of coffee beans. If, however, Starbucks agreed in March to purchase the coffee beans several months later, in July, Starbucks would not have known then what the exchange rate would be when it came time to complete the transaction. Although Starbucks would have locked in a price of BRL 7,000,000 for one million pounds of coffee beans, it would not have known what the coffee beans would cost the company in terms of US dollars.

If the US dollar appreciated so that it cost less to purchase each Brazilian real in July, Starbucks would find that it was paying less than $1,287,300 for the coffee beans. For example, suppose the dollar appreciated so that the exchange rate wasin July 2021. Then the coffee beans would only cost Starbucks

.

.

On the other hand, if the US dollar depreciated and it cost more to purchase each Brazilian real, then Starbucks would find that its dollar cost for the coffee beans was higher than it expected. If the US dollar depreciated (and the Brazilian real appreciated) so that the exchange rate wasin July 2021, then the coffee beans would cost Starbucks

On the other hand, if the US dollar depreciated and it cost more to purchase each Brazilian real, then Starbucks would find that its dollar cost for the coffee beans was higher than it expected. If the US dollar depreciated (and the Brazilian real appreciated) so that the exchange rate wasin July 2021, then the coffee beans would cost Starbucks . This uncertainty regarding the dollar cost of the coffee beans Starbucks would purchase to make its lattes is an example of transaction risk.

. This uncertainty regarding the dollar cost of the coffee beans Starbucks would purchase to make its lattes is an example of transaction risk.

- Data from Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). “Brazil / US Foreign Exchange Rate (DEXBZUS).” FRED. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed August 6, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DEXBZUS

A global company such as Starbucks has transaction risk not only because it is purchasing raw materials in foreign countries but also because it is selling its product—and thus collecting revenue—in foreign countries. Customers in Japan, for example, spend Japanese yen when they purchase a Starbucks cappuccino, coffee mug, or bag of coffee beans. Starbucks must then convert these Japanese yen to US dollars to pay the expenses that it incurs in the United States to produce and distribute these products.

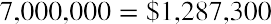

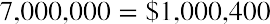

The Japanese yen–US dollar foreign exchange rates from 2011 through the first quarter of 2021 are shown in Figure 20.3. In 2012, $1.00 could be purchased with fewer than 80 Japanese yen. In 2015, it took over 120 yen to purchase $1.00.

Figure 20.3 Japanese Yen to One US Dollar8

If a company is receiving yen from customers and paying expenses in dollars, the company is harmed when the yen depreciates relative to the dollar, meaning that the yen the company receives from its customers can be exchanged for fewer dollars. Conversely, when the yen appreciates, it takes fewer yen to purchase each dollar; this appreciation of the yen benefits companies with revenues in yen and expenses in dollars.

THINK IT THROUGHProjecting Sales in US DollarsThe managers of a firm think that the exchange rate of Japanese yen to US dollars will benext year. If the company thinks that it will have sales of 50 million yen next year, how much will it project these sales will be worth in dollars? What happens if the actual exchange rate over the next year is?Solution:An exchange rate ofimplies that. If the company expects to have sales of JPY 50,000,000, it is expecting sales to be worth USD 500,000. If the exchange rate is really, this is the same as. With this exchange rate, JPY 50,000,000 in sales would be equivalent to USD 415,000. The company would receive $85,000 less from these sales in Japan than it was expecting, even if it met its goals as far as the number of units of items sold.

THINK IT THROUGHProjecting Sales in US DollarsThe managers of a firm think that the exchange rate of Japanese yen to US dollars will benext year. If the company thinks that it will have sales of 50 million yen next year, how much will it project these sales will be worth in dollars? What happens if the actual exchange rate over the next year is?Solution:An exchange rate ofimplies that. If the company expects to have sales of JPY 50,000,000, it is expecting sales to be worth USD 500,000. If the exchange rate is really, this is the same as. With this exchange rate, JPY 50,000,000 in sales would be equivalent to USD 415,000. The company would receive $85,000 less from these sales in Japan than it was expecting, even if it met its goals as far as the number of units of items sold.

- Data from Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). “Japan / US Foreign Exchange Rate (DEXJPUS).” FRED. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed August 6, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DEXJPUS

Translation Risk

In addition to the transaction risk, if Starbucks holds assets in a foreign country, it faces translation risk. Translation risk is an accounting risk. Starbucks might purchase a coffee plantation in Costa Rica for 120 million Costa Rican colones. This land is an asset for Starbucks, and as such, the value of it should appear on the company’s balance sheet.

The balance sheet for Starbucks is created using US dollar values. Thus, the value of the coffee plantation has to be translated to dollars. Because exchange rates are volatile, the dollar value of the asset will vary depending on the day on which the translation takes place. If the exchange rate is 500 colones to the dollar, then this coffee plantation is an asset with a value of $240,000. If the Costa Rican colón depreciates to 600 colones to the dollar, then the asset has a value of only $200,000 when translated using this exchange rate.

Although it is the same piece of land with the same productive capacity, the value of the asset, as reported on the balance sheet, falls as the Costa Rican colón depreciates. This decrease in the value of the company’s assets must be offset by a decrease in the stockholders’ equity for the balance sheet to balance. The loss is due simply to changes in exchange rates and not the underlying profitability of the company.

Economic Risk

Economic risk is the risk that a change in exchange rates will impact a business’s number of customers or its sales. Even a company that is not involved in international transactions can face this type of risk. Consider a company located in Mississippi that makes shirts using 100% US-grown cotton. All of the shirts are made in the United States and sold to retail outlets in the United States. Thus, all of the company’s expenses and revenues are in US dollars, and the company holds no assets outside of the United States.

Although this firm has no financial transactions involving international currency, it can be impacted by changes in exchange rates. Suppose the US dollar strengthens relative to the Vietnamese dong. This will allow US retail outlets to purchase more Vietnamese dong, and thus more shirts from Vietnamese suppliers, for the same amount of US dollars. Because of this, the retail outlets experience a drop in the cost of procuring the Vietnamese shirts relative to the shirts produced by the firm in Mississippi. The Mississippi company will lose some of its customers to these Vietnamese producers simply because of a change in the exchange rate.

Hedging

Just as companies may practice hedging techniques to reduce their commodity risk exposure, they may choose to hedge to reduce their currency risk exposure. The types of futures contracts that we discussed earlier in this chapter exist for currencies as well as for commodities. A company that knows that it will need Korean won later this year to purchase raw materials from a South Korean supplier, for example, can purchase a futures contract for Korean won.

While futures contracts allow companies to lock in prices today for a future commitment, these contracts are not flexible enough to meet the risk management needs of all companies. Futures contracts are standardized contracts. This means that the contracts have set sizes and maturity dates. Futures contracts for Korean won, for example, have a contract size of 125 million won. A company that needs 200 million won later this year would need to either purchase one futures contract, hedging only a portion of its needs, or purchase two futures contracts, hedging more than it needs. Either way, the company has remaining currency risk.

In this next section, we will explore some additional hedging techniques.

Forward Contracts

Suppose a company needs access to 200 million Korean won on March 1. In addition to a specified contract size, currency futures contracts have specified days on which the contracts are settled. For most currency futures contracts, this occurs on the third Wednesday of the month. If the company needed 125 million Korean won (the basic contract size) on the third Wednesday of March (the standard settlement date), the futures

contract could be useful. Because the company needs a different number of Korean won on a different date from those specified in the standard contract, the futures contract is not going to meet the specific risk management needs of the company.

Another type of contract, the forward contract, can be used by this company to meet its specific needs. A forward contract is simply a contractual agreement between two parties to exchange a specified amount of currencies at a future date. A company can approach its bank, for example, saying that it will need to purchase 200 million Korean won on March 1. The bank will quote a forward rate, which is a rate specified today for the sale of currency on a future date, and the company and the bank can enter into a forward contract to exchange dollars for 200 million Korean won at the quoted rate on March 1.

Because a forward contract is a contract between two parties, those two parties can specify the amount that will be traded and the date the trade will occur. This contract is similar to your agreeing with a hotel that you will arrive on March 1 and rent a room for three nights at $200 per night. You are agreeing today to show up at the hotel on a future (specified) date and pay the quoted price when you arrive. The hotel agrees to provide you the room on March 1 and cannot change the price of the room when you arrive. With a forward contract, you are also agreeing that you will indeed make the purchase and you cannot change your mind; so, using the hotel room analogy, this would mean that the hotel will definitely charge your credit card for the agreed-upon

$200 per night on March 1.

The forward contract is an individualized contract between the buyer and the seller; they are both under a contractual obligation to honor the contract. Because this contract is not standardized like the futures contract (so that it can be traded on an exchange), it can be tailored to the needs of the two parties. While the forward contract has the advantage of being fine-tuned to meet the company’s needs, it has a risk, known as counterparty risk, that the futures contract does not have. The forward contract is only as good as the promise of the counterparty. If the company enters into a forward contract to purchase 200 million Korean won on March 1 from its bank and the bank goes out of business before March 1, the company will not be able to make the exchange with a nonexistent bank. The exchanges on which futures contracts are traded guard the purchaser of a futures contract from this type of risk by guaranteeing the contract.

Natural Hedges

A hedge simply refers to a reduction in the risk or exposure that a company has to volatility and uncertainty. We have been focusing on how a company might use financial market instruments to hedge, but sometimes a company can use a natural hedge to mitigate risk. A natural hedge occurs when a business can offset its risk simply through its own operations. With a natural hedge, when a risk occurs that would decrease the value of a company, an offsetting event occurs within the firm that increases the value of the company.

As an example, consider a British-based travel agency. One of the major tours the company offers is a tour of Italy. The company arranges for transportation, lodging, meals, and sightseeing for Brits to visit the highlights of Rome, Florence, and Venice. Because the company charges customers in British pounds but must pay the bus companies, hotels, and other service providers in Italy in euros, the travel agency faces significant transaction exposure. If the value of the British pound depreciates after the company sets the price it will charge for the tour but before it pays the Italian suppliers, the company will be harmed. In fact, if the British pound depreciates by a great deal, the company could end up in a situation in which the British pounds it collects are not enough to purchase the euros it needs to pay its suppliers.

The company could create a natural hedge by offering tours of London to individuals living in the European Union. The travel agency could charge people who live in Germany, Italy, Spain, or any other country that has the euro as its currency for a travel package to London. Then the agency would pay British restaurants, tour guides, hotels, and bus companies in British pounds. This segment of the business also has currency risk. If the British pound depreciates, the company gains because the euros it collects from its EU customers will purchase more British pounds than before.

Thus, the company has created a situation in which if the British pound depreciates, the decrease in value of its tours of Italy is exactly offset by the increase in value of its tours of London. If the British pound appreciates, the opposite occurs: the company experiences a gain in its division that charges British pounds for tourists traveling to Italy and an offsetting loss in its division that charges euros for tourists traveling to London.

Options

A financial option gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to purchase or sell an asset for a specified price at some future date. Options are considered derivative securities because the value of a derivative is derived from, or comes from, the value of another asset.

Options Terminology

Specific terminology is used in the finance industry to describe the details of an options contract. If the owner of an option decides to purchase or sell the asset according to the terms of the options contract, the owner is said to be exercising the option. The price the option holder pays if purchasing the asset or receives if selling the asset is known as the strike price or exercise price. The price the owner of the option paid for the option is known as the premium.

An option contract will have an expiration date. The most common kinds of options are American options, which allow the holder to exercise the option at any time up to and including the expiration date. Holders of European options may exercise their options only on the expiration date. The labels American option and European option can be confusing as they have nothing to do with the location where the options are traded. Both American and European options are traded worldwide.

Option contracts are written for a variety of assets. The most common option contracts are options on shares of stock. Options are traded for US Treasury securities, currencies, gold, and oil. There are also options on agricultural products such as wheat, soybeans, cotton, and orange juice. Thus, options can be used by financial managers to hedge many types of risk, including currency risk, interest rate risk, and the risk that arises from fluctuations in the prices of raw materials.

Options are divided into two main categories, call options and put options. A call option gives the owner of the option the right, but not the obligation, to buy the underlying asset. A put option gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to sell the underlying asset.

Call Options

If a Korean company knows that it will need pay a $100,000 bill to a US supplier in six months, it knows how many US dollars it will need to pay the bill. As a Korean company, however, its bank account is denominated in Korean won. In six months, it will need to use its Korean won to purchase 100,000 US dollars.

The company can determine how many Korean won it would take to purchase $100,000 today. If the current exchange rate is, then it will need KWN 110,000,000 to pay the bill. The current exchange rate is known as the spot rate.

The company, however, does not need the US dollars for another six months. The company can purchase a call option, which is a contract that will allow it to purchase the needed US dollars in six months at a price stated in the contract. This allows the company to guarantee a price for dollars in six months, but it does not obligate the company to purchase the dollars at that price if it can find a better price when it needs the dollars in six months.

The price that is in the contract is called the strike price (exercise price). Suppose the company purchases a call contract for US dollars with a strike price of KWN 1,200/USD. While this contract would be for a set size, or a certain number of US dollars, we will talk about this transaction as if it were per one US dollar to highlight how options contracts work.

The company must pay a price, known as the premium, to purchase this call option contract. For our example, let’s assume the premium for the call option contract is KWN 50. In other words, the company has paid KWN 50 for the right to buy US dollars in six months for a price of KWN 1,200/USD.

In six months, the company makes a choice to either (1) pay the strike price of KWN 1,200/USD or (2) let the option expire. If the company chooses to pay the strike price and purchase the US dollars, it is exercising the option. How does the company choose which to do? It simply compares the strike price of KWN 1,200/USD to the market, or spot, exchange rate at the time the option is expiring.

If, six months from now, the spot exchange rate is, it will be cheaper for the company to buy the US dollars it needs at the spot price than it would be to buy the dollars with the option. In fact, if the spot rate is anything below, the company will not choose to exercise the option. If, however, the spot exchange rate in six months is, the company will exercise the option and purchase each US dollar for only KWN 1,200.

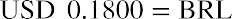

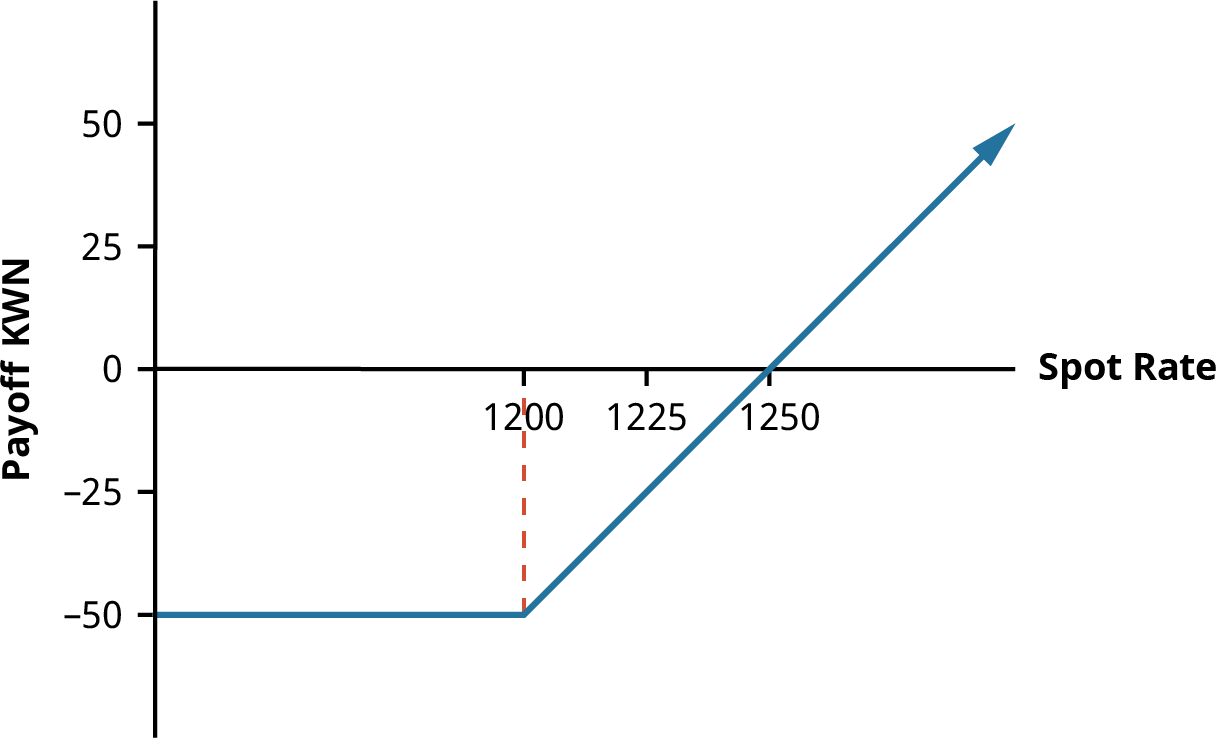

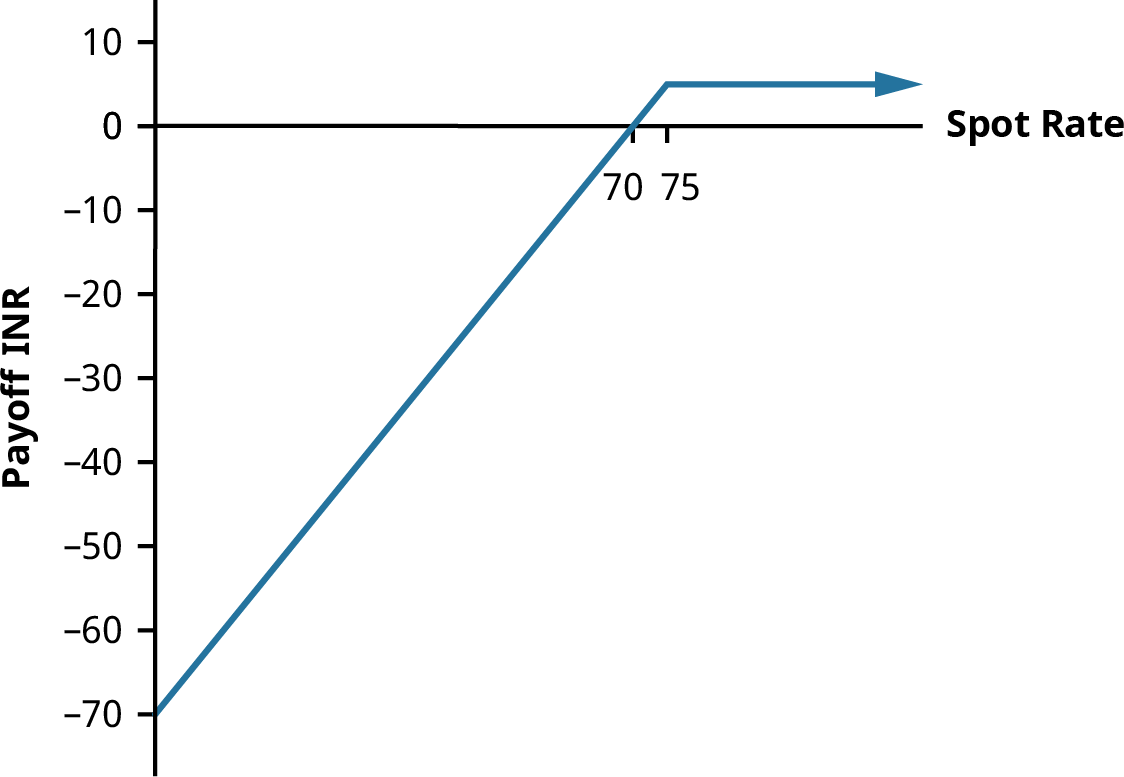

The profitability, or the payoff, to the owner of a call option is represented by the chart in Figure 20.4 below. Possible spot prices are measured from left to right, and the financial gain or loss to the company of the option contract is measured vertically. If the spot price is anything less than KWN 1,200/USD, the option expires without being exercised. The company paid KWN 50 for something that ended up being worthless.

Figure 20.4 The Payoff to the Holder of a Call Option

If, in six months, the spot exchange rate is, then the company will choose to exercise the option. The company will be saving KWN 25 for each dollar purchased, but the company originally paid 50 KWN for the contract. So, the company will be 25 KWN worse off than if it had never purchased the call option.

If the spot exchange rate is, the company will be in exactly the same position having purchased and exercised the call option as it would have been if it had not purchased the option. At any spot price higher than KWN 1,250/USD, the firm will be in a better financial position, or will have a positive payoff, because it purchased the call option. The more the Korean won depreciates over the next six months, the higher the payoff to the firm of owning the call contract. Purchasing the call contract is a way that the company can protect itself from the currency exposure it faces.

For any transaction, there must be two parties—a buyer and a seller. For the company to have purchased the call option, another party must have sold the call option. The seller of a call option is called the option writer. Let’s consider the potential benefits and risks to the writer of the call option.

When the company purchases the call option, it pays the premium to the writer. The writer of the option does not have a choice regarding whether the option will be exercised. The purchaser of the option has the right to make the choice; in essence, the writer of the option sold the right to make that decision to the purchasers of the call option.

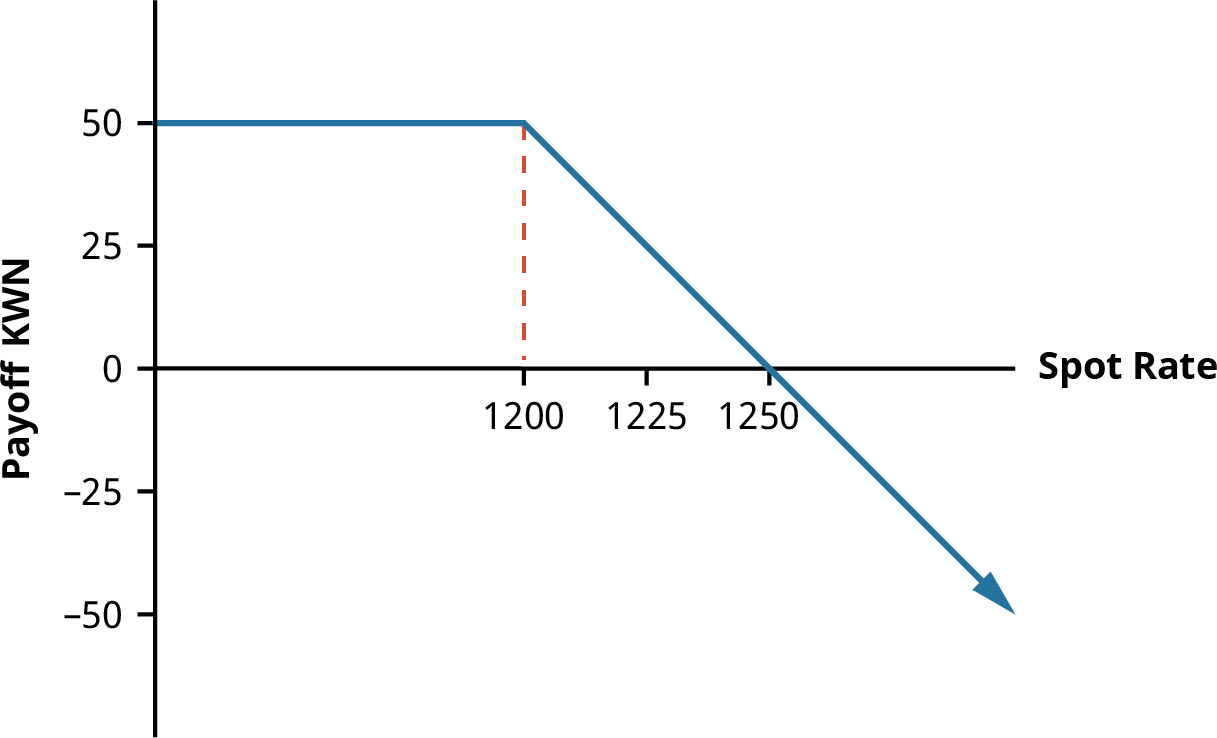

Figure 20.5 shows the payoff to the writer of the call option. Recall that the buyer of the call option will let the option expire if the spot rate is less thanwhen the call option matures in six months. If this occurs, the writer of the option collected the KWN 50 option premium when the contract was sold and then never hears from the purchaser again. This is what the writer of the option is hoping for; the writer of the call option profits when the options contract is not exercised

Figure 20.5 The Payoff to the Writer of a Call Option

If the spot rate is above, then the holder of the option will choose to exercise the right to purchase the won at the option strike price. Then the writer of the option will be obligated to sell the Korean won at a price of KWN 1,200/USD. If the spot rate is, the option writer will be obligated to sell the dollars for KWN 50 less than what they are worth; because the option writer was initially paid a KWN 50 premium for taking on that obligation, the option writer will just break even. For any exchange rate higher than, the writer of the call option will have a loss.

The option contract is a zero-sum game. Any payoff the owner of the option receives is exactly equal to the loss the writer of the option has. Any loss the owner of the option has is exactly equal to the payoff the writer of the option receives.

Put Options

While the call option you just considered gives the owner the right to buy an underlying asset, the put option gives the owner to right to sell an underlying asset. Take, for example, an Indian company that has a contract to provide graphic artwork for a US company. The US company will pay the Indian company 200,000 US dollars in three months.

While the Indian company receives US dollars, it must pay its workers in Indian rupees. Because the company does not know what the spot exchange rate will be in three months, it faces transaction risk and may be interested in hedging this exposure using a put option.

The company knows that the current spot rate is, meaning that the company would be able to use $200,000 to purchaseif it possessed the $200,000 today. If the Indian rupee appreciates relative to the US dollar over the next three months, however, the company will receive fewer rupees when it makes the exchange; perhaps the company will not be able to purchase enough

The company knows that the current spot rate is, meaning that the company would be able to use $200,000 to purchaseif it possessed the $200,000 today. If the Indian rupee appreciates relative to the US dollar over the next three months, however, the company will receive fewer rupees when it makes the exchange; perhaps the company will not be able to purchase enough

rupees to cover the wages of its employees.

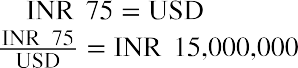

Assume the company can purchase a put option that gives it the right to sell US dollars in three months at a strike price of INR 75/USD; the premium for this put option is INR 5. By purchasing this put option, the company is spending INR 5 to guarantee that it can sell its US dollars for rupees in three months at a price of INR 75/USD.

If, in three months, when the company receives payment in US dollars, the spot exchange rate is higher than

, the company will simply exchange the US dollars for rupees at that exchange rate, allowing the put option to expire without exercising it. The payoff to the company for the option is INR -5, the premium that was paid for the option that was never used (see Figure 20.6).

Figure 20.6 The Payoff to the Holder of a Put Option

If, however, in three months, the spot exchange rate is anything less than, then the company will choose to exercise the option. If the spot rate is betweenand

, the payoff for the option is negative. For example, if the spot exchange rate is

, the company will exercise the option and receive three more Indian rupees per dollar than it would in the spot market. However, the company had to spend INR 5 for the option, so the payoff is INR -2. At a spot exchange rate of, the company has a zero payoff; the benefit of exercising the option, INR 5, is exactly equal to the price of purchasing the option, the premium of INR 5.

If, in three months, the spot exchange rate is anything below, the payoff of the put option is positive. At the theoretical extreme, if the USD became worthless and would purchase no rupees in the spot market when the company received the dollars, the company could exercise its option and receive INR 75/USD, and its payoff would be INR 70.

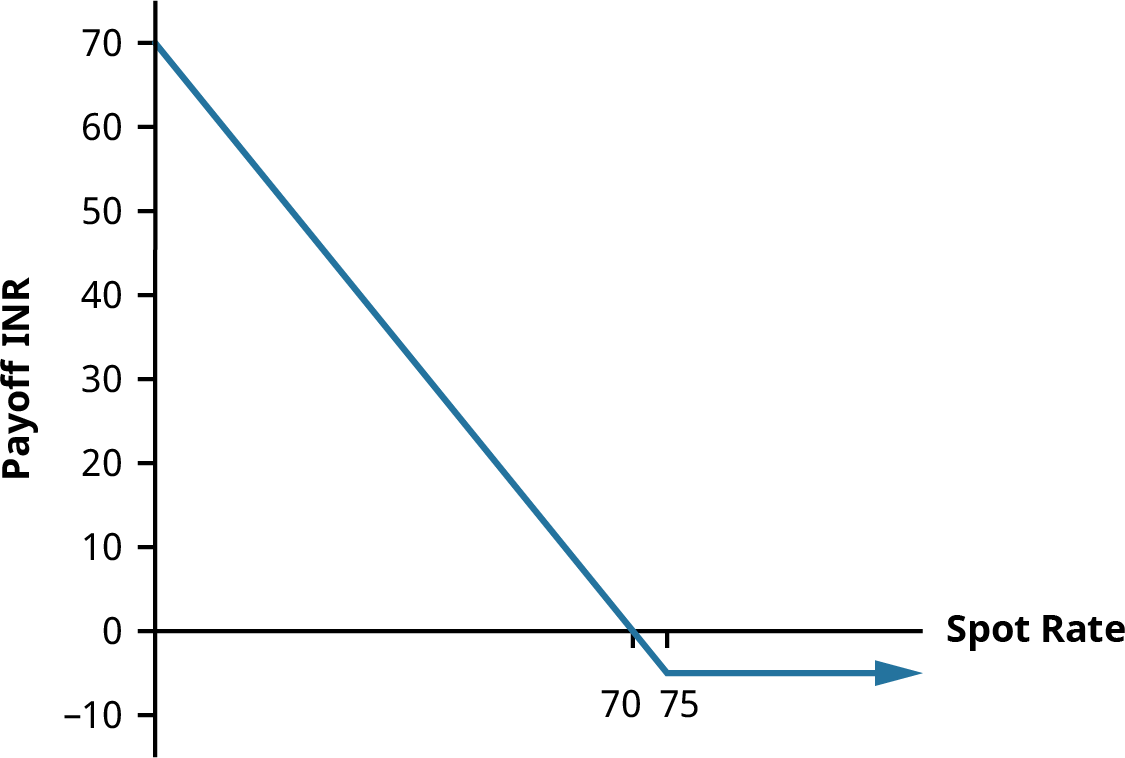

Now that we have considered the payoff to a purchaser of a put contract, let’s consider the opposite side of the contract: the seller, or writer, of the put option. The writer of a put option is selling the right to sell dollars to the purchaser of the put option. The writer of the put option collects a premium for this. The writer of the put has no choice as to whether the put option will be exercised; the writer only has an obligation to honor the contract if the owner of the put option chooses to exercise it.

The owner of the option will choose to let the option expire if the spot exchange rate is anything above

. If that is the case, the writer of the put option collects the INR 5 premium for writing the put, as shown by the horizontal line in Figure 20.7. This is what the writer of the put is hoping will occur.

Figure 20.7 The Payoff to the Writer of a Put Option

The owner of the option will choose to exercise the option if the exchange rate is less than. If the spot exchange rate is betweenand, the writer of the put option has a positive payoff. Although the writer must now purchase US dollars for a price higher than what the dollars are worth, the INR 5 premium that the writer received when entering into the position is more than enough to offset that loss.

If the spot exchange rate drops below, however, the writer of the put option is losing more than INR 5 when the option is exercised, leaving the writer with a negative payoff. In the extreme, the writer of the put will have to purchase worthless US dollars for INR 75/USD, resulting in a loss of INR 70.

Notice that the payoff to the writer of the put is the negative of the payoff to the holder of the put at every spot price. The highest payoff occurs to the writer of the put when the option is never exercised. In that instance, the payoff to the writer is the premium that the holder of the put paid when purchasing the option (see Figure 20.7).

Table 20.2 provides a summary of the positions that the parties who enter into options contract are in. Remember that the buyer of an option is always the one purchasing the right to do something. The seller or writer of an option is selling the right to make a decision; the seller has the obligation to fulfill the contract should the buyer of the option choose to exercise the option. The most the seller of an option can ever profit is by the premium that was paid for the option; this occurs when the option is not exercised.

Buyer of a callTo buyTo sellPrice of underlying risesPrice of underlying fallsPrice of underlying fallsUnlimitedPrice of underlying fallsPrice of underlying risesPrice ofPremium paidSeller of a callPremiumreceivedUnlimitedBuyer of a putTo sellStrike priceminus premium underlyingPremium paidrisesMaximum LossWhenMaximumProfitWhenthe PartyOption Contract the PartyParty to anRight ofObligation ofHarmBenefits

Table 20.2 Summary of Option Contracts

|

|

Benefits |

Harm |

|||

|

Party to anRight of |

Obligation of |

When |

Maximum Profit |

When |

Maximum Loss |

|

|

the Party |

||||

|

Seller of a put |

To buy |

Price of underlying rises |

Premium received |

Price of underlying falls |

Strike price minus premium |

Table 20.2 Summary of Option Contracts

20.4

20.4

Interest Rate Risk

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe interest rate risk.

- Explain how a change in interest rates changes the value of cash flows.

- Describe the use of an interest rate swap.

An interest rate is simply the price of borrowing money. Just as other prices are volatile, interest rates are also volatile. Just as volatility in other prices leads to uncertain cash flows for a company, volatility in interest rates can also lead to uncertain cash flows.

Measuring Interest Rate Risk

Suppose that a company is supposed to pay a bill of $1,000 in 10 years. The present value of this bill depends on the level of interest rates. If the interest rate is 5%, the present value of the bill is. If

the interest rate rises to 6%, the present value of the bill is. The increase in the interest rate by 1% causes the present value of the expected cash flow to fall by.

Interest rate risk can be highlighted by looking at bonds. Consider two $1,000 face value bonds with a 5% coupon rate, paid semiannually. One of the bonds matures in five years, and the other bond matures in 30 years. If the market interest rate is 5%, each of these bonds will sell for face value, or $1,000. If, instead, the market interest rate is 6%, the five-year bond will sell for $957.35 and the 30-year bond will sell for $861.62.

Notice that as the interest rate rises, the price of both of these bonds will fall. However, the price of the longer- term bond will fall by more than the price of the shorter-term bond. The longer-term bond price will fall by 1.38%; the shorter-term bond price will fall by only 0.43%.

Consider two additional $1,000 face value bonds. The difference is that these bonds have a 6% coupon rate, paid semiannually. If a bond has a 6% coupon rate and matures in five years, it will sell for $1,043.76 when the market interest rate is 5%. A 30-year bond that matures in 30 years and has a 6% coupon rate will sell for

$1,154.54 when the market interest rate is 5%. However, if the interest rate in the economy is 6%, both of these bonds will sell for a price of $1,000. The price of the five-year bond will drop by 4.19%; the price of the 30-year bond will drop by 13.39%.

THINK IT THROUGHCalculating Bond Prices as the Interest Rates ChangesYou are considering purchasing a $10,000 face value bond with a 4% coupon rate, paid semiannually, that matures in 20 years. If you require a 5% return to purchase this bond, what is the maximum price you

would be willing to pay for the bond? If, instead, you require an 8% return to purchase this bond, what is the maximum price you would be willing to pay for the bond?

Solution:

If the bond pays coupon interest semiannually, you will receive one-half of the face value of the bond multiplied by the coupon rate every six months. So, you will receive 40 coupon payments of

. At maturity, you will receive one lump sum of the face value of the bond. Follow the steps in Table 20.3 to calculate the price of the bond if you require a 5% return, using a financial calculator.

. At maturity, you will receive one lump sum of the face value of the bond. Follow the steps in Table 20.3 to calculate the price of the bond if you require a 5% return, using a financial calculator.

Step12345DescriptionEnterDisplayEnter the number of coupon payments you will receive40 N N =Enter your semiannual required return Enter the semiannual coupon payment Enter the face value of the bondCalculate the present value2.5 I/Y I/Y =200 PMT PMT =10000 FV FV =402.520010,000CPT PV PV =-8,744.86

Table 20.3 Calculator Step to Price a Bond Requiring a 5% Return9

When your required yield is 5%, the most you would be willing to pay for this bond is $8,744.86.

To calculate the price of the bond if your required return is 8%, use the same process, replacing the I/YR in step 2 with 4 (see Table 20.4). All other variables remain the same because the characteristics of the bond have not changed.

Step12345DescriptionEnterDisplayEnter the number of coupon payments you will receive40 N N =Enter your semiannual required return Enter the semiannual coupon payment Enter the face value of the bondCalculate the present value4 I/Y I/Y =200 PMT PMT =10000 FV FV =40420010,000CPT PV PV =-6,041.45

Table 20.4 Calculator Steps to Price a Bond Requiring an 8% Return

If your required return is 8% to invest in this bond, you will be willing to pay only $6,041.45 to purchase the bond.

Thus, if interest rates rise because of changing market conditions, the price of bonds will fall.

The sensitivity of bond prices to changes in the interest rate is known as interest rate risk. Duration is an important measure of interest rate risk that incorporates the maturity and coupon rate of a bond as well as the level of current market interest rates. Calculating duration is a complex topic that is beyond the scope of this introductory textbook, but it is useful to note that

- the higher the duration of a bond, the more sensitive the price of the bond will be to interest rate

- The specific financial calculator in these examples is the Texas Instruments BA II PlusTM Professional model, but you can use other financial calculators for these types of calculations.

changes;

- the duration of a bond will be higher when market yields are lower, all else being equal;

- the duration of a bond will be higher the longer the maturity of the bond, all else being equal; and

- the duration of a bond will be higher the lower the coupon rate on the bond, all else being equal.

Swap-Based Hedging

As the name suggests, a swap involves two parties agreeing to swap, or exchange, something. Generally, the two parties, known as counterparties, are swapping obligations to make specified payment streams.

To illustrate the basics of how an interest rate swap works, let’s consider two hypothetical companies, Alpha and Beta. Alpha is a strong, well-established company with a AAA (triple-A) bond rating. This means that Alpha has the highest rating a company can have. With this high rating, Alpha can borrow at relatively low interest rates. Often, companies in this situation will borrow at a floating rate. This means that their interest rate goes up and down as interest rates in the overall economy vary. The floating rate will be tied to a benchmark rate that is widely quoted in the financial press. Historically, companies have often used the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) as the benchmark rate. Because published quotes for LIBOR will be phased out by 2023, firms are beginning to use alternative rates. As of yet, no single alternative has emerged as the most commonly used rate; therefore, LIBOR will be used in our example. Suppose that Alpha finds that it can borrow money at rate equal to; thus, if LIBOR is 2.75%, the company will pay 3.0% to borrow. If the company wants to borrow at a long-term fixed rate, its cost of borrowing will be 5.0%.

To illustrate the basics of how an interest rate swap works, let’s consider two hypothetical companies, Alpha and Beta. Alpha is a strong, well-established company with a AAA (triple-A) bond rating. This means that Alpha has the highest rating a company can have. With this high rating, Alpha can borrow at relatively low interest rates. Often, companies in this situation will borrow at a floating rate. This means that their interest rate goes up and down as interest rates in the overall economy vary. The floating rate will be tied to a benchmark rate that is widely quoted in the financial press. Historically, companies have often used the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) as the benchmark rate. Because published quotes for LIBOR will be phased out by 2023, firms are beginning to use alternative rates. As of yet, no single alternative has emerged as the most commonly used rate; therefore, LIBOR will be used in our example. Suppose that Alpha finds that it can borrow money at rate equal to; thus, if LIBOR is 2.75%, the company will pay 3.0% to borrow. If the company wants to borrow at a long-term fixed rate, its cost of borrowing will be 5.0%.

LINK TO LEARNINGLIBOR TransitionAlthough the basic principles of financial transactions remain the same over time, the particular financial instruments used change from time to time. Innovation, regulation, and technological advances lead to these changes in financial instruments. The use of LIBOR as a benchmark rate is winding down in the early 2020s. To find out more about this transition and how it impacts companies, visit the About LIBOR Transition (https://openstax.org/r/About_LIBOR_Transition) website.

Beta has a BBB bond rating. Although this is considered a good, investment-grade rating, it is lower than the rating of Alpha. Because Beta is less creditworthy and a bit riskier than Alpha, it will have to pay a higher interest rate to borrow money. If Beta wants to borrow money at a floating rate, it will need to pay

If LIBOR is 2.75%, Beta must pay 3.5% on its floating rate debt. In order for Beta to borrow at a long-term fixed rate, its cost of borrowing will be 6.75%.

Let’s consider how these two companies can enter into a swap in which both parties benefit. Table 20.5 summarizes the situation and the rates at which Alpha and Beta can borrow. It also illustrates a way in which an interest rate swap can benefit both Alpha and Beta.

|

|

Beta |

|

|

|

Floating rate Fixed rate |

AAA

5 |

|

BBB

6.75 |

|

Rate company chooses Swap |

Fixed at 5.0 N/A |

Floating at |

N/A |

|

Beta pays Alpha fixed rate |

5.5 |

|

-5.5 |

|

Table 20.5 Example of a Swap Agreement |

|

|

|

AlphaBetaAlpha pays Beta floating rate Payments and receiptsNet amountBenefit-LIBOR+LIBOR0.75-6.250.5

AlphaBetaAlpha pays Beta floating rate Payments and receiptsNet amountBenefit-LIBOR+LIBOR0.75-6.250.5

Table 20.5 Example of a Swap Agreement

Alpha borrows in the capital markets at a fixed rate of 5%. Beta chooses to borrow at a floating rate that equals Beta also agrees to pay Alpha a fixed rate of 5.5%. In essence, Beta is paying 5.5% to

Alpha borrows in the capital markets at a fixed rate of 5%. Beta chooses to borrow at a floating rate that equals Beta also agrees to pay Alpha a fixed rate of 5.5%. In essence, Beta is paying 5.5% to

Alpha, 0.75% to its lender, and LIBOR to its lender.

In return, Alpha promises to pay Beta LIBOR. The exact amount that Alpha will pay to Beta fluctuates as LIBOR fluctuates. However, from Beta’s perspective, the payment of LIBOR it receives from Alpha exactly offsets the payment of LIBOR it makes to its lender. When LIBOR increases, the rate ofthat Beta is paying to its lender increases, but the LIBOR rate it receives from Alpha also increases. When LIBOR decreases, Beta receives less from Alpha, but it also pays less to its lender. Because the LIBOR it receives from Alpha is exactly equal to the LIBOR it pays to its lender, Beta’s net amount of interest paid is 6.25%—the 5.5% it pays to Alpha plus the 0.75% it pays to its lender.

Alpha is in the position of paying 5.0% to its lender and LIBOR to Beta while receiving 5.5% from Beta. This means that Alpha’s net interest paid isAlpha is said to have swapped its fixed interest rate for a floating rate. Because it is paying, it will experience fluctuating interest rates; however, as a company with a AAA bond rating, it is a strong, creditworthy company that can withstand that interest rate exposure. It would have cost Alphato borrow the money from its lenders at a variable rate. By participating in this swap arrangement, Alpha has been able to lower its interest rate by 0.75%.

Alpha is in the position of paying 5.0% to its lender and LIBOR to Beta while receiving 5.5% from Beta. This means that Alpha’s net interest paid isAlpha is said to have swapped its fixed interest rate for a floating rate. Because it is paying, it will experience fluctuating interest rates; however, as a company with a AAA bond rating, it is a strong, creditworthy company that can withstand that interest rate exposure. It would have cost Alphato borrow the money from its lenders at a variable rate. By participating in this swap arrangement, Alpha has been able to lower its interest rate by 0.75%.

Through this swap arrangement, Beta has been able to fix its interest rate at 6.25% rather than having a variable rate. This predictability is a benefit for a company, especially one that is in a bit more precarious position as far as its creditworthiness and stability. The 6.25% Beta pays as a result of this arrangement is 0.5% below the 6.75% it would have paid if it simply borrowed from its lenders at a fixed rate.

Summary

Summary

The Importance of Risk Management

Risk arises due to uncertainty. The future is unpredictable. One job of the financial manager is to manage the risks of both cash inflows and cash outflows. Investors are risk-averse. The riskier a firm’s cash flows are, the higher the rate of return investors require to provide capital to the company.

Commodity Price Risk

Companies do not know how much they will have to pay for raw materials in future months. The price of raw materials will change as economic conditions change, impacting a company’s cost of goods sold and profits. Some ways that a company can hedge this risk are through vertical integration, long-term contracts, and futures contracts.

Exchange Rates and Risk

Exchange rates are unpredictable. This leads to transaction risk, translation risk, and economic risk as currency values change. A forward contract is an agreement between two parties to make an exchange at a particular rate on a given date in the future. Companies can use options to mitigate the risks. A call option gives the holder the right, but not the obligation, to purchase an underlying asset. A put option give the holder the right, but not the obligation, to sell an underlying asset.

Interest Rate Risk

When interest rates increase, the present value of future cash flows decreases. Duration is a measure of interest rate risk. A swap involves two parties agreeing to exchange something, often specified payment streams.

Key Terms

Key Terms

American option an option that the holder can exercise at any time up to and including the exercise date

appreciate when one unit of a currency will purchase more of a foreign currency than it did previously

call option an option that gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to buy the underlying asset at a specified price on some future date

depreciate when one unit of a currency will purchase less of a foreign currency than it did previously

derivative a security that derives its value from another asset

duration a measure of interest rate risk

economic risk the risk that a change in exchange rates will impact the number of customers a business has or its sales

European option an option that the holder can exercise only on the expiration date

exchange rate the price of one currency in terms of another currency

exercise price (strike price) the price the option holder pays for the underlying asset when exercising an option

exercising choosing to purchase or sell the asset underlying a held option according to the terms of the option contract

expiration date the date an option contract expires

forward contract a contractual agreement between two parties to exchange a specified amount of assets on a specified future date

futures contract a standardized contract to trade an asset on some future date at a price locked in today

hedging taking an action to reduce exposure to a risk

margin the collateral that must be posted to guarantee that a trader will honor a futures contract

marking to market a procedure by which cash flows are exchanged daily for a futures contract, rather than at the end of the contract

natural hedge when a company offsets the risk that something will decrease in value by having a company activity that would increase in value at the same time

option an agreement that gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to purchase or sell an asset at a specified price on some future date

option writer seller of a call or put option

premium the price a buyer of an option pays for the option contract

put option an option that gives the owner the right, but not the obligation, to sell the underlying asset at a specified price on some future date

speculating attempting to profit by betting on the uncertain future, knowing that a risk of loss is involved

spot rate the current market exchange rate

strike price (exercise price) the price an option holder pays for the underlying asset when exercising the option

swap an agreement between two parties to exchange something, such as their obligations to make specified payment streams

transaction risk the risk that a change in exchange rates will impact the value of a business’s expected receipts or expenses

translation risk the risk that a change in exchange rates will impact the value of items on a company’s financial statements

vertical integration the merger of a company with its supplier