16 Lesson 11 and 12 Working Capital and Accounts Payable Financing

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many families and small businesses realized the importance of financial resiliency. In personal finance, financial resiliency is the ability to overcome financial difficulties such as sudden job loss or significant unexpected expenses—to spring back quickly.

To help promote resiliency, personal financial planners advise clients to maintain liquid assets equal to three to six months of living expenses, keep debt levels low, manage the household budget, keep insurance in force (health, property, and life), establish a solid credit history, and make wise use of credit cards and home equity lines of credit.

In business finance, financial resiliency is not important only during pandemics but is important through the ups and downs of seasonal cycles and economic downturns. Managing cash, accounts receivable, and inventory while making optimal use of trade credit (accounts payable) makes for a business that meets its operating needs and pays its debts when due.

Working capital management is also critical during good times. Even though profits might be rising, a business with growing demand for its products and services still needs to have working capital management tools to pay its bills. Growth in sales and profits do not immediately mean sufficient cash flow, so planning ahead with tools such as a cash budget is key.

19.1

19.1

What Is Working Capital?

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define working capital.

- Calculate a firm’s operating cycle and cash cycle.

- Compute inventory days, accounts receivable days, and accounts payable days.

The concept of business capital is often associated with the cash and assets (such as land and equipment) that the owners contributed to the business. Early political economists like Adam Smith and Karl Marx identified this concept of capital, along with labor and entrepreneurship, to be the factors of production.

That general idea of capital is important and critical to a company’s productive capacity. This chapter is about a specific type of capital— working capital—that is just as important as long-term capital. Working capital describes the resources that are needed to meet the daily, weekly, and monthly operating cash flow needs.

Employees are paid out of working capital as well as cash from operations, the fulfillment of merchandise orders is possible because of working capital, and the liquidity of a company hinges upon how well management plans and controls working capital.

Understanding working capital begins with the concept of current assets—those resources of a business that are cash, near cash, or expected to be turned into cash within a year through the normal operations of the business. Current assets are necessary for the everyday operation of the firm, and they are synonymous with term gross working capital.

Cash is needed to pay the bills and meet the payroll. Excess cash is invested in cash alternatives such as marketable securities, creating liquidity that can be tapped when operating cash flow needs exceed the amount of cash on hand (checking account balances). Investment in inventory is necessary to meet the demand for products (sales), and if the firm extends credit to its customers so that a sale can be made, the balance sheet will also show accounts receivable—a very common current asset that derives its value from the probability that customers will pay their bills.

Working capital is often spoken about in two versions: gross working capital and net working capital. As was previously stated, gross working capital is equivalent to current assets, particularly those that are cash, cash- like, or will be converted to cash within a short period of time (i.e., in less than one year).

Net working capital (NWC) is a more refined concept of working capital. It is best understood by examining its formula:

Goal of Working Capital Management

The goal of working capital management is to maintain adequate working capital to

- meet the operational needs of the company;

- satisfy obligations (current liabilities) as they come due; and

- maintain an optimal level of current assets such as cash (provides no return), accounts receivable, and inventory.

Working capital management encompasses all decisions involving a company’s current assets and current liabilities. One very important aspect of working capital management is to provide enough cash to satisfy both maturing short-term obligations and operational expenditures—keeping the company sufficiently liquid.

In summary, working capital management helps a company run smoothly and mitigates the risk of illiquidity. Well-run companies make effective use of current liabilities to finance an optimal level of current assets and maintain sufficient cash balances to meet short-term operating goals and to satisfy short-term obligations. Working capital management is accomplished through

- cash management;

- credit and receivables management;

- inventory management; and

- accounts payable management.

Components of Working Capital Management

In contrast to net working capital, gross working capital is synonymous with current assets, particularly those current assets that are either cash or cash equivalents or that will be converted to cash within a short period of time (i.e., in less than one year).

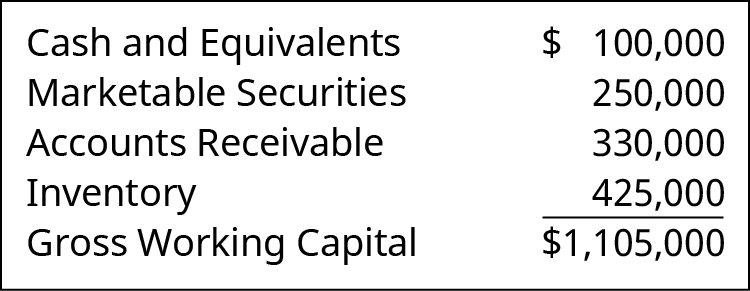

Below is a list of the components of gross working capital.

- Cash and cash equivalents

- Marketable securities

- Accounts receivable

- Inventory

Here is an example. On December 31, a company has the following balances and gross working capital:

Think of the $1,105,000 of gross working capital as a source of funds for the most pressing obligations (i.e., current liabilities) of the company. Gross working capital is available to pay the bills. However, some of the current assets would need to be converted to cash first. Accounts receivable need to be collected, and inventory would need to be sold before it too can become cash. What if the company had $600,000 of current liabilities? That amount of current obligations could not be paid out of cash until the marketable securities were sold and a significant portion of accounts receivable were collected.

The second, more refined and useful concept of working capital is net working capital:

For example, if a company has $1,000,000 of current assets and $750,000 of current liabilities, its net working capital would be $250,000 ($1,000,000 less $750,000).

NWC provides a better picture because it takes into account the liability “coverage” provided by the current assets. As the above example shows, the current assets would “cover” the current liabilities with an excess of

$250,000. Think of it this way: if the current assets could be converted to cash, they could be used to meet the current obligations with another $250,000 of cash leftover.

Current liabilities include

- accounts payable;

- dividends payable;

- notes payable (due within a year);

- current portion of deferred revenue;

- current maturities of long-term debt;

- interest payable;

- income taxes payable; and

- accrued expenses such as compensation owed to employees.

Net working capital possibilities can be thought of as a spectrum from negative working capital to positive, as

explained in Table 19.1.

Negative Net Working CapitalZero Net Working CapitalPositive Net Working Capital

Current liabilities are greater than current assets.

Could indicate a liquidity problem. There is difficulty satisfying current obligations.

Current assets equal current liabilities.

Indicates that current assets could cover current obligations. However, there is no positive margin (safety cushion) or “liquid reserve” to satisfy unexpected cash needs.

Current assets are greater than current liabilities.

Indicates that the company can meet its current obligations.

However, excessively high net working capital could mean too little cash and therefore an opportunity cost (forgoing rates of return on alternative investment).

Table 19.1 Spectrum of Net Working Capital

Measures of Financial Health provides information on a variety of financial ratios to help users of financial statements understand the strengths and weakness of companies’ financial statements. Three of the financial ratios covered in that chapter are brought back into this chapter’s discussion to demonstrate how financial managers examine working capital and liquidity. Liquidity is the ease with which an asset can be converted into cash. Those ratios are the current ratio, the quick ratio, and the cash ratio. A higher ratio indicates a greater level of liquidity.

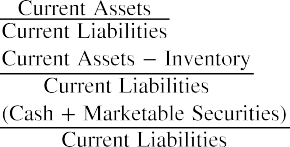

The formulas for the three liquidity ratios are:

The formulas for the three liquidity ratios are:

Notice how the current ratio includes the two elements of net working capital—current assets and current liabilities. It makes for a quick comparison of relative size or proportion.

THINK IT THROUGHCurrent RatioA company has $2,000,000 of current assets, while its current liabilities are $1,000,000. What is the current ratio, and what does it mean?Solution:The current ratio would bewhich is a 2:1 proportion of current asset value to the amount of the current liabilities. This means that if all the current assets could be converted to cash, then the current liabilities could be satisfied two times.

THINK IT THROUGHCurrent RatioA company has $2,000,000 of current assets, while its current liabilities are $1,000,000. What is the current ratio, and what does it mean?Solution:The current ratio would bewhich is a 2:1 proportion of current asset value to the amount of the current liabilities. This means that if all the current assets could be converted to cash, then the current liabilities could be satisfied two times.

There are two drawbacks to the current ratio: (1) it is a working capital analytic as of a point in time but is not indicative of future liquidity or future cash flows and (2) as an indicator of liquidity, it can be deceptive if a significant proportion of the current assets are inventory, supplies, or prepaid expenses. Inventory is not very liquid as it can take an extended time period to convert to cash, and assets such as supplies and prepaid expenses never become cash and therefore are not a source of funds to pay bills.

The quick ratio is considered a more conservative indication of liquidity since it does not include a firm’s

inventory:.

THINK IT THROUGHQuick RatioA company’s current assets total $2,000,000, but $500,000 of that is inventory and the current liabilities total$1,000,000. What is the quick ratio, and what does it mean?Solution:The quick ratio would beand would indicate a smaller cushion of net working capital.

THINK IT THROUGHQuick RatioA company’s current assets total $2,000,000, but $500,000 of that is inventory and the current liabilities total$1,000,000. What is the quick ratio, and what does it mean?Solution:The quick ratio would beand would indicate a smaller cushion of net working capital.

THINK IT THROUGHCash RatioThe cash ratio is even more conservative in that it presents a picture of liquidity by excluding all current assets except cash and marketable securities.A company’s total current assets are $2,000,000, but only $1,100,000 of the current assets consist of cash and marketable securities. Assuming $1,000,000 of current liabilities, what would be the cash ratio and what does it mean?Solution:The cash ratio would beand the amount of cash is enough to pay the current bills by $100,000.

THINK IT THROUGHCash RatioThe cash ratio is even more conservative in that it presents a picture of liquidity by excluding all current assets except cash and marketable securities.A company’s total current assets are $2,000,000, but only $1,100,000 of the current assets consist of cash and marketable securities. Assuming $1,000,000 of current liabilities, what would be the cash ratio and what does it mean?Solution:The cash ratio would beand the amount of cash is enough to pay the current bills by $100,000.

Working capital ratios, like any financial ratio, are most valuable when examined in light of trends and in comparison to industry/peer averages. For example, a deteriorating current ratio over several quarters (a decline in the company’s current ratio) could indicate a reduced ability to pay bills.

Working capital ratios are also compared to industry averages, which are available in databases produced by such financial publishers as Dun & Bradstreet, Dow Jones Company, and the Risk Management Association (RMA). These information services are available via subscriptions and through many libraries. For example, if a company’s current ratio is 0.9 while the industry average is 2.0, then the company is less liquid than the average company in its industry and strategies, and techniques need to be considered to change things and to better compete with peer groups. Industry averages can be aspirational, motivating management to set liquidity goals and best practices for working capital management.

It is common to think about working capital with a simple assumption: current assets are being “financed” by current liabilities. However, such an assumption may be an oversimplification. Some level of current assets is often necessary to meet longer-term obligations, and in that way, you could think of some amount of current assets as a permanent based of working capital that may need to be financed with longer-term sources of capital.

Think of a company with seasonal business. During busy times, more working capital will be needed than during certain other portions of the year, such as less busy times. But there will always be some level—a permanent base—of working capital needed. Think of it this way: the total working capital of many companies will ebb and flow depending on many variables such as the operating cycle, production needs, and the growth of revenue. Therefore, working capital can be thought of as having a permanent base that is always needed

and a total working capital amount that increases when activity levels (i.e., production and sales volume) are higher (see Figure 19.2).

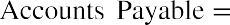

The Cash Cycle

The cash cycle, also called the cash conversion cycle, is the time period between when a business begins production and acquires resources from its suppliers (for example, acquisition of materials and other forms of inventory) and when it receives cash from its customers. This is offset by the time it takes to pay suppliers (called the payables deferral period).

Figure 19.2 Working Capital Needs Can Vary: Temporary and Permanent Working Capital

The cash cycle is measured in days, and it is best understood by examining its formula:

The inventory conversion period is also called the days of inventory. It is the time (days) it takes to convert inventory to sales and is calculated by following these steps:

First, calculate the Inventory Turnover Ratio using this formula:

First, calculate the Inventory Turnover Ratio using this formula:

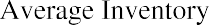

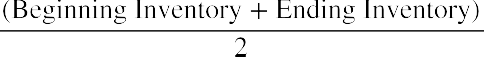

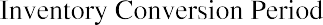

The Average Inventory is arrived at as follows:

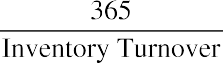

- Then, use the Inventory Turnover Ratio to calculate the Inventory Conversion Period:

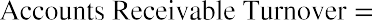

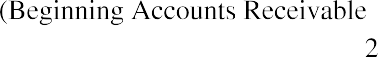

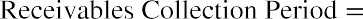

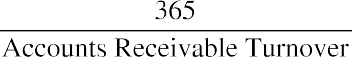

The receivables collection period, also called the days sales outstanding (DSO) or the average collection period, is the number of days it typically takes to collect cash from a credit sale. It is calculated by following these steps:

First, calculate the Accounts Receivable Turnover using this formula:

First, calculate the Accounts Receivable Turnover using this formula:

The Average Accounts Receivable is arrived at as follows:

Then, use the Accounts Receivable Turnover to calculate the Receivables Collection Period:

Then, use the Accounts Receivable Turnover to calculate the Receivables Collection Period:

The payables deferral period, also known as days in payables, is the average number of days its takes for a company to pay its suppliers. It is calculated by following these steps:

First, calculate the Accounts Payable Turnover using this formula:

First, calculate the Accounts Payable Turnover using this formula:

The Average Accounts Payable is arrived at as follows:

- Then, use the Accounts Payable Turnover to calculate the Payables Deferral Period:

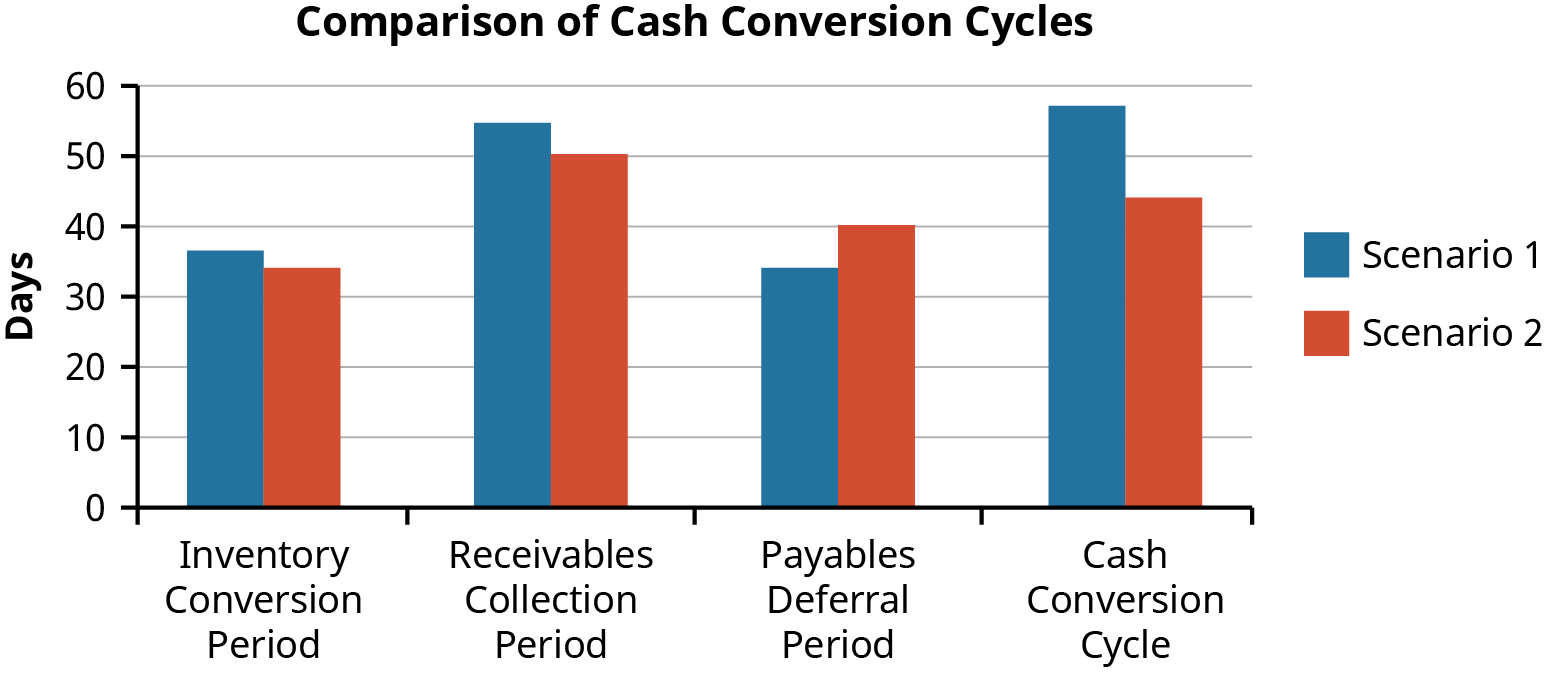

THINK IT THROUGHPeriods of the Cash CycleScenario 1: King Sized Products (KSP) Inc. has annual credit sales of $40,000,000. The average inventory is$3,000,000, and the company has average accounts receivable of $6,000,000 and average accounts payable of $2,800,000. The cost of goods sold for KSP Inc. is $30,000,000. The cash cycle for the company is 57.2 days. Calculate the inventory conversion, receivables collection, and payable deferral periods.Solution:Inventory conversion period:••Receivables collection period:••Payables deferral period:••The solution (the entire cash conversion cycle) is also illustrated in a chart, Figure 19.3.

THINK IT THROUGHPeriods of the Cash CycleScenario 1: King Sized Products (KSP) Inc. has annual credit sales of $40,000,000. The average inventory is$3,000,000, and the company has average accounts receivable of $6,000,000 and average accounts payable of $2,800,000. The cost of goods sold for KSP Inc. is $30,000,000. The cash cycle for the company is 57.2 days. Calculate the inventory conversion, receivables collection, and payable deferral periods.Solution:Inventory conversion period:••Receivables collection period:••Payables deferral period:••The solution (the entire cash conversion cycle) is also illustrated in a chart, Figure 19.3.

Figure 19.3 Cash Conversion Cycle

Figure 19.3 Cash Conversion Cycle

Shortening the inventory conversion period and the receivables collection period or lengthening the payables deferral period shortens the cash conversion cycle. Financial managers monitor and analyze each component of the cash conversion cycle. Ideally, a company’s management should minimize the number of days it takes to convert inventory to cash while maximizing the amount of time it takes to pay suppliers.

Quickly converting inventory to sales speeds up cash inflows and shortens the cash cycle, but it also could help reduce inventory losses as a result of obsolescence. Inventory becomes obsolete because of a variety of factors including time—inventory that has not been sold for a long period of time and is not expected to be sold in the future has to be written down or written off according to accounting rules. Write-offs of inventory can result in significant losses for a company. In the food business, inventory conversion periods take on great importance because of spoilage of perishable goods; in retailing, seasonal items lose value the longer they stay on the shelves.

Various inventory management techniques are used to shorten production time in manufacturing, and in retailing, strategies are used to reduce the amount of time a product sits on the shelf or is stored in the warehouse. Production techniques such as just-in-time inventory systems and marketing and pricing strategies can have an impact on the number of days in the inventory conversion cycle.

For the receivables collection period, a relatively long receivables collection period means that the company is having trouble collecting cash from its customers and so whatever can be done to speed up collections while still offering competitive credit terms should be pursued by financial managers. For example, companies that converted paper invoicing to e-invoicing most likely reduce the average collection period by some number of days, as it makes sense that if a bill is transmitted electronically, lag time is cut (no delays because of “snail mail”) and collections (payments back to the company from customers) may happen sooner. Other credit management techniques, some of which are explained in subsequent sections, can help minimize and control the receivables collection period.

The payables deferral period is the one element that probably cannot be optimized without violating credit terms. Certainly, cash balances can be conserved by delaying payments to vendors for as long as possible; however, payments on trade credit need to be made on time or the company’s relationship with the supplier can suffer. In a worst-case scenario, the company’s credit rating could also deteriorate.

A credit rating, also called a credit score, is a measure produced by an independent agency indicating the

likelihood that a company will meet its financial obligations as they come due; it is an indication of the company’s ability to pay its creditors. Three business credit rating services are Equifax Small Business, Experian Business, and Dun & Bradstreet.

THINK IT THROUGH

The Cash Conversion Cycle

Considering the previous Think It Through (Scenario 1), what if you could reduce inventory levels, hold lower accounts receivable balances, and rely more heavily on accounts payable while maintaining the same sales level?

Here’s Scenario 2. Because of better inventory management, credit and collections management, and negotiation of longer payment periods with vendors, King Sized Products (KSP) Inc. needs less investment in inventory and accounts receivable and is able to utilize a greater amount of trade credit financing.

Annual credit sales are $40,000,000, average inventory is $2,800,000, average accounts receivable are

$5,500,000, average accounts payable are $3,300,000, and cost of goods sold is $30,000,000. What is the cash conversion cycle?

Solution:

Inventory conversion period:

•

•

•

Receivables collection period:

•

•

Payables deferral period:

•

•

Notice that the investment in inventory and accounts receivable is less and the average accounts payable is more with no change in credit sales and cost of goods sold—you would certainly anticipate a reduction in the cash conversion cycle. The improvement would be about 13 days (from 57.2 in Scenario 1 to 44.1 days in Scenario 2). Figure 19.4 shows a bar chart comparison of the two scenarios.

|

Scenario 1 Scenario 2 |

||

|

|

36.50 |

34.07 |

|

Receivables Collection Period |

54.75 |

50.21 |

|

Payables Deferral Period |

34.07 |

40.15 |

|

Cash Conversion Cycle |

57.18 |

44.10 |

|

Table 19.2 |

|

|

Figure 19.4 Scenario 1 and 2 Comparison: Shortening the Cash Conversion Cycle

Figure 19.4 Scenario 1 and 2 Comparison: Shortening the Cash Conversion Cycle

LINK TO LEARNINGA Harvard Business School blog post, How Amazon Survived the Dot-Com Bubble (https://openstax.org/r/ how-amazon-survived), discusses how Amazon managed its cash conversion cycle to the point where it was receiving payment for the things it sold before Amazon had to pay for them. In that way, Amazon had a negative cash conversion cycle (which is really a huge positive for a company trying to manage positive cash flow!).

Working Capital Needs by Industry

When comparing working capital needs by industry, you can see some variation. For example, some companies in the grocery business can have very low cash conversion cycles, while construction companies can have very high cash conversion cycles. And some companies, like those in the restaurant business, can have very low numbers and even have negative cash conversion cycles.

Working capital can also differ from one industry to another. An often cited general rule is that a current ratio of 2 is considered optimal. However, general rules of thumb must be treated with caution. A better benchmarking approach is to compare a firm’s ratios—current ratio and quick ratios—to the average of the industry in which the subject company operates.

Take, for example, a home construction company. Such as firm has a long operating cycle because of the production process (building homes), and the “storage of finished goods” can result in very high current ratios—such as 11 or 12 times current liabilities—whereas a retailer like Walmart or Target would have much lower current ratios.

In recent years, Walmart Stores Inc. (NYSE: WMT) has had a current ratio of around 0.9 and has been able to manage its working capital needs by efficient management of its supply chain, quick turnover of inventory, and a very small investment in accounts receivables.1 Big retailers like Walmart are effective at negotiating favorable payment terms with their vendors. The ability to generate consistent positive cash flow from operations allows a retailer like Walmart to operate with relatively low amounts of working capital.

The credit policies of a company also affect working capital. A company with a liberal credit policy will require a greater amount of working capital, as collection periods of accounts receivable are longer and therefore tie up

- Walmart Inc. “2020 Annual Report.” 2020. https://corporate.walmart.com/media-library/document/2020-walmart-annual- report/_proxyDocument?id=00000171-a3ea-dfc0-af71-b3fea8490000

more dollars in receivables.

Almost all businesses will have times when additional working capital is needed to pay bills, meet the payroll (salaries and wages), and plan for accrued expenses. The wait for the cash to flow into the company’s treasury from the collection of receivables and cash sales can be longer during tough times.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the US government made paycheck protection program (PPP) loans available to help alleviate working capital problems for small and large business when the economy slowed because of shutdowns and social distancing. And although 60 percent of the PPP loan proceeds were to go to cover payroll-related costs, 40 percent could be used to bolster working capital to meet rent, utilities costs, and some interest expense while companies were “treading water”—waiting for positive cash flow to pick up under a recovery.2

It isn’t just during downturns that working capital is strained. Growing companies, even if they are extremely profitable, need additional working capital as they ramp up operations by acquiring raw materials, component parts, supplies, or other forms of inventory; hiring temporary or additional employees; and taking on new projects. Whenever additional resources are needed, working capital is also needed.

Some of the current assets and expenditures needed in a growing company may need to be financed from sources that are not spontaneous financing—trade credit (accounts payable). Such forms of external financing such as lines of credit, short-term bank loans, inventory-based loans (also called floor planning), and the factoring of accounts receivables might have to be relied upon.

19.2

19.2

What Is Trade Credit?

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Compute the cost of trade credit.

- Define cash discount.

- Define discount period.

- Define credit period.

Trade credit, also known as accounts payable, is a critical part of a business’s working capital management strategy. Trade credit is granted by vendors to creditworthy companies when those companies purchase materials, inventory, and services.

A company’s purchasing system is usually integrated with other functions such production planning and sales forecasting. Purchasing managers search for and evaluate vendors, negotiate order quantities, and prepare purchase orders. In carrying out the purchasing process, credit terms are granted by the company’s vendors and purchases of inventory and services can be made on trade credit accounts—allowing the purchaser time to pay. The purchaser carries an accounts payable balance until the account is paid.

Trade credit is referred to as spontaneous financing, as it occurs spontaneously with the gearing up of operations and the additional investment in current assets. Think of it this way: If sales are increasing, so too is production. Increased sales mean more current assets (accounts receivable and inventory), and increased sales mean increases in accounts payable (financing happening spontaneously with increased sales and inventory purchases). Compared to other financing arrangements, such as lines of credit and bank loans, trade credit is convenient, simple, and easy to use.

Once a company is approved for trade credit, there is no paperwork or contracts to sign, as is the case with various forms of bank financing. Invoices specify the credit terms, and there is usually no interest expense associated with trade credit. Accounts payable is a type of obligation that is interest-free and is distinguished from debt obligations, such as notes payable, that require the creditor to pay back principal and interest.

- US Small Business Administration. “PPP Loan Forgiveness.” n.d. https://www.sba.gov/funding-programs/loans/covid-19-relief- options/paycheck-protection-program/ppp-loan-forgiveness

How Trade Credit Works

Trade credit is common in B2B (business to business) transactions and is analogous to consumer spending using a credit card. With a credit card, a consumer opens an account with a credit limit. Most trade credit is offered to a company with an open account that has a credit limit up to which the company can purchase goods or services without having to pay the cash up front. As long as the payments are made in accordance with the terms of the agreement (also called credit terms), no interest or additional fees are charged on the credit balance except possibly for a fee for late payment.

Initially, the vendor’s credit department approves both a trade credit limit and credit payment terms (i.e., number of days after the invoice date that payment is due). Timely payments on accounts payable (trade credit) helps create a credit history for the purchasing firm.

Trade Credit Terms

Trade credit arrangements often carry credit terms that offer an incentive, called a discount, for a company (the buyer) to pay its bill within a relatively short period of time. Net terms, also referred to as the full credit period, are the number of days that a business (purchaser) has before they must pay their invoice. A common net term is Net 30, with payment due in full within 30 days of the invoice.

Many vendors also offer cash discounts to customers that pay their bill early. A company’s invoice that specifies payment terms of “2/10 n/30” (stated as: “two ten net 30”) would allow a 2 percent discount if the buyer’s account balance is paid within 10 days of the invoice date; otherwise, the net amount owed would be due in 30 days. The “10 days” in the example is the discount period—the number of days the buyer has to take advantage of the cash discount for an early payment, also known as quick payment.

For example, Jackson’s Premium Jams Inc. received a $10,500 invoice for the purchase of jelly jars. The invoice has payment terms of 2/10 n/30. Jackson’s pays the bill within 10 days of the invoice date. Jackson’s payment would be . The effect of taking a discount because of a quick payment is a lowering of the cost of inventory in the case of purchases of materials (for a manufacturer), merchandise (for a retailer or wholesaler), and operating expenses (for any company that “buys” services using trade credit). In Cost of Trade Credit, there is an example that shows the high annualize opportunity cost (36.73 percent) of not taking advantage of cash discounts.

. The effect of taking a discount because of a quick payment is a lowering of the cost of inventory in the case of purchases of materials (for a manufacturer), merchandise (for a retailer or wholesaler), and operating expenses (for any company that “buys” services using trade credit). In Cost of Trade Credit, there is an example that shows the high annualize opportunity cost (36.73 percent) of not taking advantage of cash discounts.

CONCEPTS IN PRACTICETrade Credit of International TradeWhen international trade occurs, two important documents are commonly required: a letter of credit and a bill of lading. A letter of credit is issued by a financial institution on behalf of the foreign buyer (importer). The bill of lading is a legal document that gives proof of a contract between a transportation company and the buyer and is one important piece of documentation that allows the buyer to draw on the letter of credit. A bill of lading serves as a document of title and proof of receipt of goods by the shipper.The letter of credit secures a promise of payment to the seller (exporter) provided that the terms of the sale are met. For an international trade transaction, the letter of credit is the main mechanism that establishes a liability for the buyer. Instead of a trade payable, the buyer uses a line of credit from a bank.

Cost of Trade Credit

Trade credit is often referred to as a no-cost type of financing. Unlike with other credit arrangements (e.g., bank loans, lines of credit, and commercial paper), there is usually no interest expense associated with trade credit, and as long as your account does not become delinquent, there are no special fees. Some accounts payable arrangements specify an interest penalty or a late fee when the account goes delinquent, but as long

as payments are made on time, trade credit is thought of as a low-cost source of working capital.

However, there is one possible cost associated with trade credit for companies that don’t take advantage of cash discounts when offered by sellers. Using accounts payable to purchase goods and services can involve an opportunity cost—a cost of the forgone opportunity of making a quick payment and benefiting from a cash discount. A business that does not take advantage of a cash discount for early payment of trade credit will pay more for goods and services than a business that routinely takes advantage of discounts.

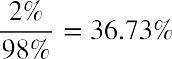

The annual percentage rate of forgoing quick payment discounts can be estimated with the following formula:

The annual percentage rate of forgoing quick payment discounts can be estimated with the following formula:

Example: Novelty Accessories Inc. (NAI) purchases products from a vendor that offers credit payment terms of 2/10, net 30. The annual cost to NAI of not taking advantage of the discount for quick payment is 36.73 percent.

Example: Novelty Accessories Inc. (NAI) purchases products from a vendor that offers credit payment terms of 2/10, net 30. The annual cost to NAI of not taking advantage of the discount for quick payment is 36.73 percent.

19.3

19.3

Cash Management

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain why firms hold cash.

- List instruments available to a financial manager for investing cash balances.

Cash management means efficiently collecting cash from customers and managing cash outflows. To manage cash, the cash budget—a forward-looking document—is an important planning tool. To understand cash management, you must first understand what is meant by cash holdings and the motivations (reasons) for holding cash. A cash budget example is covered in Using Excel to Create the Short-Term Plan.

Cash Holdings

The cash holdings of a company are more than the currency and coins in the cash registers or the treasury vault. Cash includes currency and coins, but usually those amounts are insignificant compared to the cash holdings of checks to be deposited in the company’s bank account and the balances in the company’s checking accounts.

Motivations for Holding Cash

The initial answer to the question of why companies hold cash is pretty obvious: because cash is how we pay the bills—it is the medium of exchange. The transactional motive of holding cash means that checks and electronic funds transfers are necessary to meet the payroll (pay the employees), pay the vendors, satisfy creditors (principal and interest payments on loans), and reward stockholders with dividend payments. Cash for transaction is one reason to hold cash, but there is another reason—one that stems from uncertainty and the precautions you might take to be ready for the unexpected.

Just as you keep cash balances in your checking and savings accounts and even a few dollars in your wallet or purse for unexpected expenditures, cash balances are also necessary for a business to provide for unexpected events. Emergencies might require a company to write a check for repairs, for an unexpected breakdown of equipment, or for hiring temporary workers. This motive of holding cash is called the precautionary motive.

Some companies maintain a certain amount of cash instead of investing it in marketable securities or in upgrades or expansion of operations. This is called the speculative motive. Companies that want to quickly take advantage of unexpected opportunities want to be quick to purchase assets or to acquire a business, and a certain amount of cash or quick access to cash is necessary to jump on an opportunity.

Sometimes cash balances may be required by a bank with which a company conducts significant business. These balances are called compensating balances and are typically a minimum amount to be maintained in the company’s checking account.

For example, Jack’s Outback Restaurant Group borrowed $500,000 from First National Bank and Trust. As part of the loan agreement, First National Bank required Jack’s to keep at least $50,000 in its company checking account as a way of compensating the bank for other corporate services it provides to Jack’s Outback Restaurant Group.

Cash Alternatives

Cash that a company has that is in excess of projected financial needs is often invested in short-term investments, also known as cash equivalents (cash alternatives). The reason for this is that cash does not earn a rate of return; therefore, too much idle cash can affect the profitability of a business.

Table 19.3 shows a list of typical investment vehicles used by corporations to earn interest on excess cash. Financial managers search for opportunities that are safe and highly liquid and that will provide a positive rate of return. Cash alternatives, because of their short-term maturities, have low interest rate risk (the risk that an investment’s value will decrease because of changes in market interest rates). In that way, prudent investment of excess cash follows the risk/return trade-off; in order to achieve safe returns, the returns will be lower than the possible returns achieved with risky investments. Cash alternative investments are not committed to the stock market.

US Treasury bills Obligations of the US government with maturities of 3 and 6 months

Federal agency securities

Certificates of deposit

Commercial paper

Obligations of federal government agencies such as the Federal Home Loan Bank and the Federal National Mortgage Association

Issued by banks, a type of savings deposit that pays interest

Short-term promissory notes issued by large corporations with maturities ranging from a few days to a maximum of 270 days

Table 19.3 Typical Cash Equivalents

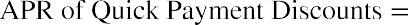

Figure 19.5 shows a note within the 2021 Annual Report (Form 10-K) of Target Corporation. The note discloses the amount of Target’s cash and cash equivalent balances of $8,511,000,000 for January 30, 2021, and

$2,577,000,000 for February 1, 2020.

Figure 19.5 Note from Target Corporation 2021 10-K Filing (source: US Securities and Exchange Commission/EDGAR)

In that note, which is a supplement to the company’s balance sheet, receivables from third-party financial institutions is also considered a cash equivalent. That is because purchases by Target’s customers who use their credit cards (e.g., VISA or MasterCard) create very short-term receivables—amounts that Target is waiting to collect but are very close to a cash sale. So instead of being reported as accounts receivable—a line item on the Target balance sheet that is separate from cash and cash equivalents—these amounts receivable from third-party financial institutions are considered part of the cash and cash equivalents and are a very liquid asst. For example, the amount of $560,000,000 for January 30, 2021, is considered a cash equivalent since the settlement of these accounts will happen in a day or two with cash deposited in Target’s bank accounts. When a retailer sells product and accepts a credit card such as VISA, MasterCard, or American Express, the cash collection happens very soon after the credit card sale—typically within 24 to 72 hours.3

Companies also invest excess funds in marketable securities. These are debt and equity investments such as corporate and government bonds, preferred stock, and common stock of other entities that can be readily sold on a stock or bond exchange. Ford Motor Company has this definition of marketable securities in its 2019 Annual Report (Form 10-K):

“Investments in securities with a maturity date greater than three months at the date of purchase and other securities for which there is more than an insignificant risk of change in value due to interest rate, quoted price, or penalty on withdrawal are classified as Marketable securities.”4

19.4

19.4

Receivables Management

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss how decisions on extending credit are made.

- Explain how to monitor accounts receivables.

For any business that sells goods or services on credit, effective accounts receivable management is critical for cash flow and profitability planning and for the long-term viability of the company. Receivables management begins before the sale is made when a number of factors must be considered.

- Can the customer be approved for a credit sale?

- Creditcardprocessing.com. “How Long Does it Take for a Merchant to Receive Funds?” n.d. https://www.creditcardprocessing.com/resource/article/long-take-merchant-receive- funds/#:~:text=The%20time%20that%20it%20takes,days%20to%20process%20the%20payment

- Ford Motor Company. “2019 Annual Report.” n.d. https://s23.q4cdn.com/725981074/files/doc_downloads/Ford-2019-Printed- Annual-Report.pdf

- If the credit is approved, what will be the credit terms (i.e., how long do we give customers to pay their bills)?

- Will there be a cash discount for quick payment?

- How much credit should be extended to each customer (credit limit)?

Accounts receivable is not about accepting credit cards. Credit card sales are not technically accounts receivable. When a credit card is accepted, it means that the credit card company (e.g., VISA, MasterCard, or American Express) will guarantee the payment. The cash will be deposited in the merchant’s bank account in a very short period of time.

When a business makes a sale on account, management (e.g., a credit manager or analyst) does its best to distinguish between customers who have a high likelihood of paying and customers who have a low likelihood. Customers with low credit risk are approved; the decision is based on an effective analysis of creditworthiness.

Creditworthiness is judged by looking at a number of factors including an evaluation of the customer’s financial statements, financial ratios, and credit reports (credit scores) based on a customer’s payment history on credits owed to other firms. If a company has a prior relationship with a customer seeking trade credit, the customer’s payment history with the firm is also carefully evaluated before additional credit is granted.

LINK TO LEARNINGCorporate Finance InstituteCredit managers use various tools and techniques to evaluate creditworthiness of customers. The Corporate Finance Institute’s website states that “the ‘5 Cs of Credit’ is a common phrase used to describe the five major factors [character, capacity, collateral, capital, and conditions] used to determine a potential borrower’s creditworthiness.” It goes on to say that “a credit report provides a comprehensive account of the borrower’s total debt, current balances, credit limits, and history of defaults and bankruptcies, if any.”5 More on the 5 Cs of credit can be found on the Corporate Finance Institute’s website (https://openstax.org/ r/corporate-finance).

Determining the Credit Policy

A company’s credit policy encompasses rules of credit granting and procedures for the collections of accounts. It’s how a company will process credit applications, utilize credit scoring and credit bureaus, analyze financial statements, make credit limit decisions, and conduct collection efforts when accounts become delinquent (still outstanding after their due date).

Establishing Credit Terms

Trade credit terms were discussed earlier. Recall that part of the terms and conditions of a sale are the credit terms—elements of a sales agreement (contract) that indicate when payment is due, possible discounts (for quick payments), and any late fee charges.

If open credit is for a sales transaction, an agreement is made as to the length of time for which credit is to be granted (payment period) and a discount for early payment. Although companies are free to establish credit terms as they see fit, most companies look to the practice of the particular industry in which they operate. The credit terms offered by the competition are a factor. Net terms usually range between 30 days and 90 days, depending on the industry. Discounts for early payments also differ and are typically from 1 to 3 percent.

Establishing credit terms offered can be thought of as a decision process similar to setting a price for products and services. Just as a price is the result of a market forces, so too are credit terms. If credit terms are not

- Corporate Finance Institute. “What Are the 5 Cs of Credit?” n.d. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/ credit/5-cs-of-credit/

competitive within the industry, sales can suffer. Typically, companies follow standard industry credit terms. If most companies in an industry offer a discount for early payments, then most companies will follow suit and also offer an equal discount.

Once credit terms are established, they can be changed based on both marketing strategies and financial management goals. For example, discounts for early payments can be more generous, or the full credit period can be extended to stimulate additional sales. Both discount periods and full credit periods can be tightened to try to speed up collections. The establishment of and changes to credit terms are usually made in consultation with the sales and financial management departments.

Monitoring Accounts Receivables

Financial managers monitor accounts receivables using some basic tools. One of those tools is the accounts receivable aging schedule (report). To prepare the aging schedule, a classifying of customer account balances is performed with age as the sorting attribute.

An account receivable begins its life as a credit sale. The age of a receivable is the number of days that have transpired since the credit sale was made (the date of the invoice). For example, if a credit sale was made on June 1 and is still unpaid on July 15, that receivable is 45 days old. Aging of accounts is thought to be a useful tool because of the idea that the longer the time owed, the greater the possibility that individual accounts receivable will prove to be uncollectible.

An aging schedule is a report that organizes the outstanding (unpaid) receivable balances into age categories. The receivables are grouped by the length of time they have been outstanding, and an uncollectible percentage is assigned to each category. The length of uncollectible time increases the percentage assigned. For example, a category might consist of accounts receivable that are 0–30 days past due and is assigned an uncollectible percentage of 6 percent. Another category might be 31–60 days past due and is assigned an uncollectible percentage of 15 percent. All categories of estimated uncollectible amounts are summed to get a total estimated uncollectible balance.

The aging of accounts is useful to the credit and collection managers, both from a global view—estimating how much of the accounts receivable asset might be bad debts—and on a micro basis—being able to drill down to see which specific customers are slow paying or delinquent so as to implement collection tactics.

Accountants and auditors also find the aging of accounts to determine a reasonable amount to be reported as bad debt expense and to establish a sufficient balance in the allowance for doubtful accounts. Bad debt expense is the cost of doing business because some customers will not pay the amounts they owe (accounts receivable), while the allowance for doubtful accounts is a contra-asset (it will be deducted from accounts receivable on the balance sheet) that contains management’s best guess (management’s estimate) as to how much of its accounts receivable will never be collected.

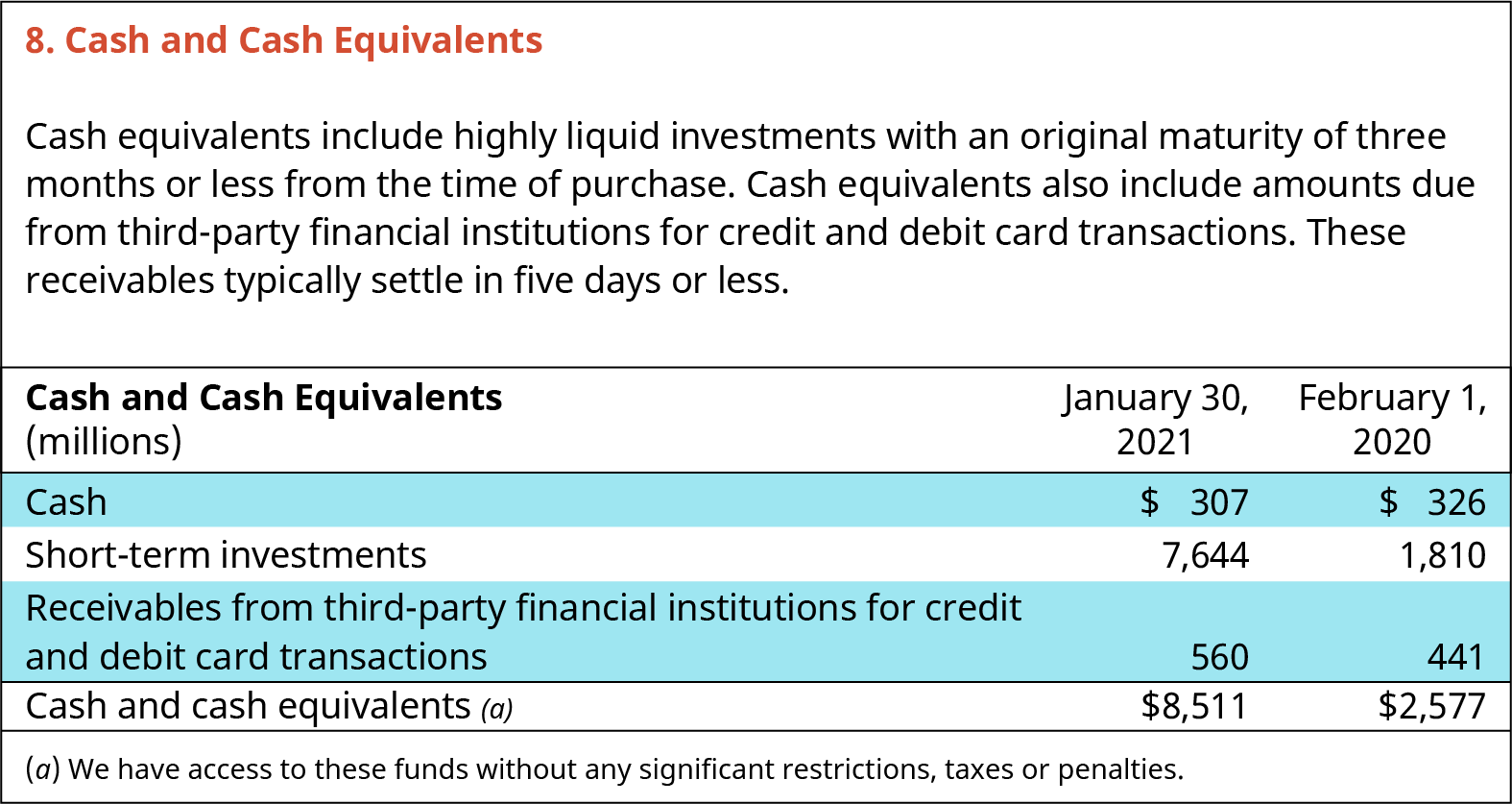

In Figure 19.6, Foodinia Inc.’s accounts receivable aging report shows that the total receivables balance is

$189,000. The company splits its accounts into four age categories: not due, 30 to 60 days past due, 61 to 90 days past due, and more than 90 days past due. Of the $189,000 owed to Foodinia by its customers, $75,500 ($189,000 less $113,500) of invoices have been outstanding (not paid yet) beyond their due dates.

Figure 19.6 Foodinia Inc. Aging of Accounts Receivable Schedule

In addition to preparing aging schedules, financial managers also use financial ratios to monitor receivables. The accounts receivable turnover ratio determines how many times (i.e., how often) accounts receivable are collected during an operating period and converted to cash. A higher number of times indicates that receivables are collected quickly. In contrast, a lower accounts receivable turnover indicates that receivables are collected at a slower rate, taking more days to collect from a customer.

Another receivables ratio is the number of days’ sales in receivables ratio, also called the receivables collection period—the expected days it will take to convert accounts receivable into cash. A comparison of a company’s receivables collection period to the credit terms granted to customers can alert management to collection problems. Both the accounts receivable turnover ratio and receivables collection period are covered, including the formulas for calculating the ratios, in the previous section of this chapter.

Accounts Receivables and Notes Receivable

An accounts receivable is an informal arrangement between a seller (a company) and customer. Accounts receivable are usually paid within a month or two. Accounts receivable don’t require any complex paperwork, are evidenced by an invoice, and do not involve interest payments. In contrast, a note receivable is a more formal arrangement that is evidence by a legal contract called a promissory note specifying the payment amount and date and interest.

The length of a note receivable can be for any time period including a term longer than the typical account receivable. Some notes receivable have a term greater than a year. The assets of a bank include many notes receivable (a loan made by a bank is an asset for the bank).

A note receivable can be used in exchange for products and services or in exchange for cash (usually in the case of a financial lender). Sometimes a company might request that a slow-paying customer sign a note promissory note to further secure the receivable, charge interest, or add some type of collateral to the arrangement, in which case the receivable would be called a secured promissory note. Several characteristics of notes receivable further define the contract elements and scope of use (see Table 19.4).

Accounts ReceivableNotes Receivable

- An informal agreement between customer and company

- Receivable in less than one year or within a company’s operating cycle

- Does not include interest

A legal contract with established payment terms- Receivable beyond one year and outside of a company’s operating cycle

- Includes interest

- Could stipulate collateral

Table 19.4 Key Feature Comparison of Accounts Receivable and Notes Receivable

19.5

19.5

Inventory Management

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Outline the costs of holding inventory.

- Outline the benefits of holding inventory.

Financial managers must consider the impact of inventory management on working capital. Earlier in the chapter, the concept of the inventory conversion cycle was covered. The number of days that goods are held by a business is one of the focal points of inventory management.

Managers look to minimize inventory balances and raise inventory turnover ratios while trying to balance the needs of operations and sales. Purchasing personnel need to order enough inventory to “feed” production or to stock the shelves. The sales force wants to meet or surpass their sales budgets, and the operations people need inventory for the factories, warehouses, and e-commerce sites.

The days in inventory ratio measures the average number of days between acquiring inventory (i.e., purchasing merchandise) and its sale. This ratio is a metric to be watched and monitored by inventory managers and, if possible, minimized. A high days in inventory ratio could mean “aging” inventory. Old inventory could mean obsolesce or, in the case of perishable goods, spoilage. In either case, old inventory means losses.

Imagine a company selling high-tech products such as consumer electronics. A high days in inventory ratio could mean that technologically obsolete products will be sold at a discount. There are similar issues with older inventory in the fashion industry. Last year’s styles are not as appealing to the fashion-conscious consumer and are usually sold at significant discounts. In the accounting world, lower of cost or market value is a test of inventory value to determine if inventory needs to be “written down,” meaning that the company takes an expense for inventory that has lost significant value. Lower of cost or market is required by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) to state inventory valuations at realistic and conservative values.

Inventory is a very significant working capital component for many companies, such as manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers. For those companies, inventory management involves management of the entire supply chain: sourcing, storing, and selling inventory. At its very basic level, inventory management means having the right amount of stock at the right place and at the right time while also minimizing the cost of inventory. This concept is explained in the next section.

Inventory Cost

Controlling inventory costs minimizes working capital needs and, ultimately, the cost of goods sold. Inventory management impacts profitability; minimizing cost of goods sold means maximizing gross profit (Gross Profit

= Net Sales Less Cost of Goods Sold).

There are four components to inventory cost:

- Purchasing costs: the invoice amount (after discounts) for inventory; the initial investment in inventory

- Carrying costs: all costs of having inventory in stock, which includes storage costs (i.e., the cost of the space to store the inventory, such as a warehouse), insurance, inventory obsolescence and spoilage, and even the opportunity cost of the investment in inventory

- Ordering costs: the costs of placing an order with a vendor; the cost of a purchase and managing the payment process

- Stockout costs: an opportunity cost incurred when a customer order cannot be filled and the customer goes elsewhere for the product; lost revenue

Minimizing total inventory costs is a combination of many strategies, the scope and complexity of which are beyond the scope of this text. Concepts such as just-in-time (JIT) inventory practices and economic order quantity (EOQ) are tools used by inventory managers, both of which help keep a company lean (minimizing inventory) while making sure the inventory resources are in place in time to complete the sale.

Benefit of Holding Inventory

Brick-and-mortar stores need goods in stock so that the customer can see and touch the product and be able to acquire it when they need it. Customers are disappointed if they cannot see and touch the item or if they find out upon arrival at the store that it is out of stock.

Customers of all kinds don’t want to wait for the delivery of a purchase. We have become accustomed to Amazon orders being delivered to the door the next day. Product fulfillment and availability is important. Inventory must be in stock, or sales will be lost.

In manufacturing, the inventory of materials and component parts must be in place at the start of the value chain (the conversion process), and finished goods need to be ready to meet scheduled shipments. Holding sufficient inventory meets customer demand, whether it is products on the shelves or in the warehouse that are ready to move through the supply chain and into the hands of the customer.

19.6

19.6

Using Excel to Create the Short-Term Plan

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Create a one-year budget.

- Create a cash budget.

A cash budget is a tool of cash management and therefore assists financial managers in the planning and control of a critical asset. The cash budget, like any other budget, looks to the future. It projects the cash flows into and out of the company. The budgeting process of a company is a really an integrated process—it links a series of budgets together so that company objectives can be achieved. For example, in a manufacturing company, a series of budgets such as those for sales, production, purchases, materials, overhead, selling and administrative costs, and planned capital expenditures would need to be prepared before cash needs (cash budget) can be predicted.

Just as you might budget your earnings (salary, business income, investment income, etc.) to see if you will be able to cover your expected living expenses and planned savings amounts, to be successful and to increase the odds that sufficient cash will be available in the months ahead, financial managers prepare cash budgets to

- meet payrolls;

- allocate dollars for contingencies and emergencies;

- analyze if planned collections and disbursements policies and procedures result in adequate cash balances; and

- plan for borrowings on lines of credit and short-term loans that might be needed to balance the cash budget.

A cash budget is a model that often goes through several iterations before managers can approve it as the

plan going forward. Changes in any of the “upstream” budgets—budgets that are prepared before the cash budget, such as the sales, purchases, and production budgets—may need to be revised because of changing assumptions. New economic forecasts and even cost-cutting measures will require a revision of the cash budget.

Although a budget might be prepared for each month of a future 12-month period, such as the upcoming fiscal year, a rolling budget is often used. A rolling budget changes often as the planning period (e.g., a fiscal year) plays out. When one month ends, another month is added to the end (the next column) of the budget. For example, if in your budget January is the first month of the planning period, once January is over, next January’s cash budget column would be added—right after December’s column (at the far right of the budget).

Sample One-Year (Annual) Operating Budget

Preparing an annual operating budget can be a complex task. In essence, a company budget is a series of budgets, many of which are interrelated.

The sales budget is prepared first and has an impact on many other budgets. Take the example of a production budget of a manufacturer. The sales budget impacts what needs to be produced (production budget), and the production budget influences planned purchases of material (purchases budget), overhead resources (overhead budget), and the amount of labor costs for the year ahead (direct labor budget.)

For a merchant (such as a wholesaler or retailer), the annual budget would be less complex than that of a manufacturing firm but would still require an inventory purchases budget and an operating expense budget (such as selling and administrative expenses). For a service firm, a purchase budget for inventory would not be necessary, but an operating budget would be. All businesses need a cash budget, which is the topic of the next section of this chapter.

The example operating budget presented here is of a merchandising company. Budgets are prepared following a process that begins with a sales (or revenue) forecast. The sales forecast is normally based on information obtained from both internal and external sources and predicts the amount of units to be sold in the planning period—usually one year into the future.

A company’s management, in consultation with its marketing and sales executives, would prepare a sales budget by making assumptions about the number of units that are expected to be sold and the prices that will be charged. From the sales budget, projections are made as to cash receipts each month, and therefore assumptions have to be made as to how much of each month’s sales will be cash sales and how much cash will flow into the company from the collection credit sales (including cash flow in from the prior month’s sales).

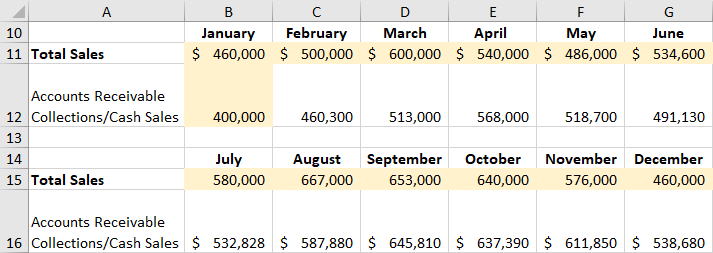

Figure 19.7 provides an example of a sales budget and projected accounts receivable collections and cash sales for the months of January through December. Keep in mind that projected monthly sales amounts are not equal to cash collected from sales. Because of sales on credit, some cash from sales lags credit sales as collections can extend beyond the month of sale. Credit terms such terms such as net 30 (net amount owed to be paid in 30 days) have to be considered when developing a forecasted cash collection pattern.

Figure 19.7 Example of a Sales and Collections Budget

Download the spreadsheet file (https://openstax.org/r/spreadsheet-file1) containing key Chapter 19 Excel exhibits.

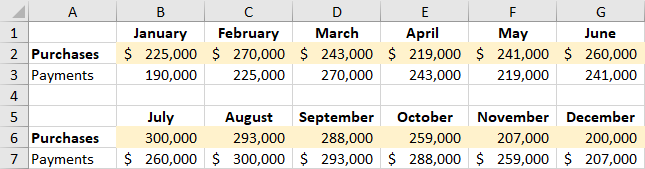

Sales budgets “drive” the preparation of other budgets. If sales are expected to increase, purchases of inventory and some operating expenses would also increase. To meet the demand for goods and services (as defined in the sales budget), a purchases (inventory) budget would be prepared. In this example (Figure 19.8), the purchases budget shows projected purchases of inventory (merchandise) and the projected payments (also called disbursements) for each month.

Cash outflows as a result of purchases often do not equal the projected purchase amount. That is because payments for purchases are usually on credit (accounts payable), and so purchases for one month typically get spread out over a period of time that encompasses the current month and the month (or months) thereafter. To keep this example simple, the assumption is that the purchases are paid for in the following month (an average days payable outstanding of 30 days). However, in other cases, payment patterns may be based on other payment periods such as 45, 60, or even 90 days, depending on the trade credit terms.

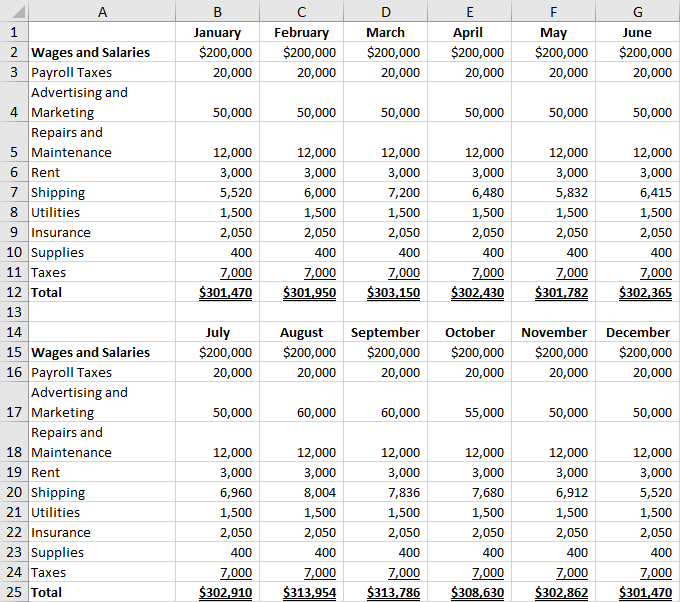

An operating expense budget is prepared next and is basically a prediction of the selling and administrative expenditures of the company. Notice in Figure 19.9 that in the operating expense budget, cost of goods sold (an expense) is not included, nor are noncash expenses such as depreciation. The cash outlays related to goods sold, at least in a merchandising operation, are accounted for in the purchases budget (payments for purchases of inventory.)

With the sales, purchases, and operating expense budgets prepared, the cash budget can be prepared. Some of the “inputs” to the cash budget are from the sales (collections of cash), purchases (payments), and the operating expense budget (cash expenditures for selling and administrative expenses). A sample cash budget and a discussion of its preparation follows in the next section of this chapter.

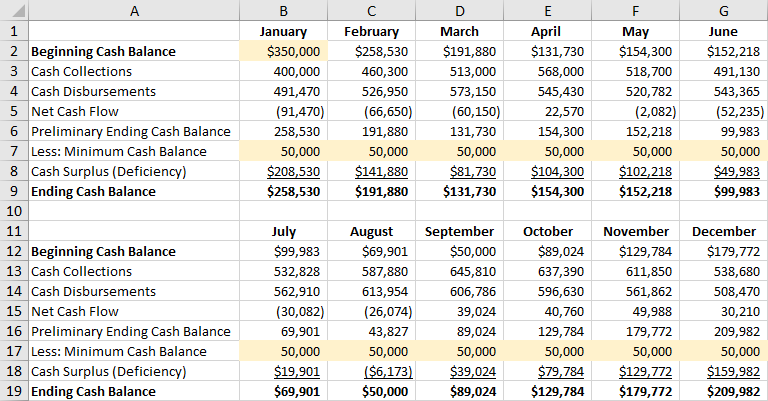

Sample Cash Budget

A cash budget is the last budget to be prepared and is often part of the financial budget (cash budget, budgeted income statement, and budgeted balance sheet). The purpose of the cash budget is to estimate cash flows, to help ensure sufficient cash balances are maintained during the planning period, and to plan for external financing during periods of cash deficits.

When a budget is prepared in Excel, cash budget analysts can play “what if” with different scenarios to see when cash surpluses and deficits are expected. Cash surpluses means that funds can be invested in marketable securities to earn a rate of return, while cash deficits mean that financing, such as a line of credit, will be necessary (assuming forecasts are accurate).

Although the example shown in Figure 19.10 is a monthly cash budget, a cash budget could be prepared using any useful time elements: weekly, monthly, or quarterly.

One common practice is to use a rolling cash budget. A rolling cash budget is continually updated to add a new budget period, such as a month’s amount of cash flow activity, as the most recent budgeted month expires. For example, assume that a 12-month cash budget is prepared for a period covering January 20X1 to December 20X1. Once the month of January 20X1 has concluded, a 12-month planning period continues by add January 20X2 to the last column of the budget. The rolling cash monthly budget is an extension of the initial cash budget model, adding one month and thereby always extending cash flow projections one year into the future.

Figure 19.9 Operating Expenses Budget

Figure 19.10 Sample Cash Budget

Using Figure 19.9 as an example, Table 19.5 shows the formulas that form the skeleton of a monthly cash budget.

Cash Collections

Cash

This is the amount of cash the company expects to have on the first day of the month. For example, in Figure 19.10, cell B2 is the amount of cash on Jan. 1 to start the year (the planning period). The remaining beginning cash balances for the months February through December are the ending cash balances of the previous month. For example, February’s beginning cash balance (C2) is referenced from cell B9 (ending cash balance for January).

These are the projected cash inflows from collections from customers (accounts receivable), cash sales, and any other significant cash inflows, such as dividends and interest on investments or sale of fixed assets. For example, the Cash Collections shown in the Sample Cash Budget (Figure 19.10) are referenced from the Sales and Collections Budget (Figure 19.7). January’s Cash Collections (cell B3) in the Sample Cash Budget are from cell B12 of the Sales and Collection Budget.

Cash disbursements are the projected cash outflows, such as those for operating expenses and payment of payables. For example, Cash Disbursements in the Sample Cash Budget for

Disbursements January (Figure 19.10) are the sum of January’s payments for purchases in the Purchases Budget (Figure 19.8, cell B3) and the January operating expenses (Operating Expenses

Budget, Figure 19.9, cell B12).

Net Cash Flow The formula for net cash flow is For example, in Figure 19.10, the January Net Cash Flow is calculated in cell B5.

Preliminary Ending Cash Balance

Less:

Beginning Cash Balance + or – Net Cash Flow. This is the projected cash balance before taking into account the target cash balance to be maintained (minimum cash balance). In the Sample Cash Budget (Figure 19.10), the preliminary ending cash balance formula for January is =B2+B5 (B2 is the Beginning Cash Balance and B5 is the Net Cash Flow for the month).

This is a target cash balance that management sets; it is the minimum amount of cash that

Minimum Cash should be maintained by the company (in Figure 19.10, cells B2:G7 and B17:G17). Balance

Table 19.5 Excel Formulas for Monthly Cash Budget

A cash surplus means that cash can be invested in marketable securities. A cash deficiency means that some type of financing, such as a line of credit or bank loan, will be needed to provide enough cash for operations and to maintain a minimum cash balance. This number isCash Surplusfound by subtracting the minimum cash balance from the preliminary ending cash balance. (Deficiency)For example, the cash surplus for January in Figure 19.10 is calculated with this formula:=B6-B7. Notice that all months in the Sample Cash Budget show a surplus except for August’s forecast of a deficit, which may require drawing on a line of credit to provide enough cash to meet obligations in August.

Table 19.5 Excel Formulas for Monthly Cash Budget

Summary

Summary

What Is Working Capital?

Working capital is not only necessary to run a business; it is a resource that will expand and contract with business cycles and must be carefully managed and monitored. The daily, weekly, and monthly needs of business operations are met by cash. Financial managers understand the significance of net working capital (current assets – current liabilities) and various liquidity ratios as they attempt to ensure that bills can be paid. The cash conversion cycle and the cash budget provide additional working capital management tools.

What Is Trade Credit?

Trade credit is very prevalent in the business world, especially in B2B (business-to-business) transactions. Many business exchanges (sales) could not take place without trade credit and the credit terms that are offered. Like any component of working capital, trade credit must be planned and managed. The creditor (the company granting the credit) does so based on an analysis of creditworthiness and must monitor payments and manage slow-paying accounts. The debtor (accounts payable) needs to make payments on time to keep a clean credit history and to take advantage of discounts.

Cash Management

Cash management is simply making sure you have enough cash to meet expected obligations and for contingencies (unexpected or emergency cash needs). Excess cash should be invested low-risk and highly liquid marketable securities. The cash budget is a critical tool of cash management.

Receivables Management

Accounts receivables are monitored by management with tools such as the ratios accounts receivable turnover and average collection period and the aging of receivables. The credit managers’ mantra rings true: “The older the receivable, the greater the likelihood that the account will not be collected.”

Inventory Management

Inventory, usually the least liquid of the current assets, presents its own set of management challenges. Finding the optimal level of inventory is probably more of an art than a science. JIT helps to reduce the investment in inventory and lower the costs of storage, but stockout costs can be very damaging to profitability.

Using Excel to Create the Short-Term Plan

Short-term plans of a business are funded with cash, with cash budgets being a critical tool of planning. The cash budget takes into account a target amount of cash, factoring in all the motives for holding cash. A cash budget looks ahead—predicting cash inflows and outflows, allocating for minimum cash balances to be maintained, and helping management determine short-term financing needed. Although it is the last budget prepared, the preparation of the cash budget is an important financial planning exercise of companies small and large.

Key Terms

Key Terms

accounts receivable aging schedule a report that shows amounts owed by customers by the age of the account, as measured by the number of days since the sale

allowance for doubtful accounts an account that contains the estimated amount of accounts receivable that will not be collected

bad debt expense an expense that a business incurs as a result of uncollectible accounts receivables

bankruptcies federal court procedures that protect distressed businesses from creditor collection efforts while allowing the debtor firm to liquidate its assets or devise a reorganization plan

benchmarking the process of performance analysis that involves comparing financial condition and operating results against a standard, called a benchmark

bill of lading a document that is a detailed list of a goods that have been shipped; a receipt given by the carrier (shipping company) to the seller as evidence that the goods have been shipped to the buyer

carrying costs all costs associated with having inventory in stock including storage costs, insurance, inventory obsolescence, and spoilage

cash budget a report that shows an estimation of cash inflows, outflows, and cash balances over a specific period of time, such as monthly, quarterly, or annually

cash cycle or cash conversion cycle the time period (measured in days) between when a business begins production and acquires resources from its suppliers (for example, acquisition of materials and other forms of inventory) and when it receives cash from its customers; offset by the time it takes to pay suppliers (called the payables deferral period)

cash discount discount granted to a customer who has purchased goods or services on account (credit) and pays the invoice within a certain number of days as specified by credit terms

compensating balance minimum balance of cash that a business must deposit and maintain in a bank account to obtain a loan

contra-asset an account with a balance that is used to offset (reduce) its related asset on the balance sheet (for example, allowance for doubtful accounts reduces the value of accounts receivable reported on the balance sheet)

credit period the number of days that a business purchaser has before they must pay their invoice

credit rating a type of score that indicates a business’s creditworthiness

credit terms the terms that are part of a sales credit agreement that indicate when payment is due, possible discounts, and any fees that will be charged for a late payment

current assets assets that are cash or cash equivalents or are expected to be converted to cash in a short period of time and will be consumed, used, or expire through business operations within one year or the business’s operating cycle, whichever is shorter

discount period the number of days the buyer has to take advantage of the cash discount for an early payment

factoring the process of selling accounts receivables to a financial institution or, in some cases, using the accounts receivables as security for a loan from a financial institution

floor planning a type of inventory financing whereby a financial institution provides a loan so that the company can acquire inventory with proceeds from the sale of inventory used to pay down the loan; a common method of financing inventory for automobile dealers and sellers of other big-ticket (high-priced) items

gross working capital synonymous with the current assets of a company, those assets that include cash and other assets that can be converted into cash within a period of 12 months

just-in-time inventory inventory management method in which a company maintains as little inventory on hand as possible while still being able to satisfy the demands of its customers

letter of credit a letter issued by a bank that is evidence of a guarantee for payments made to a specified entity (such as a supplier) under specified conditions; common in international trade transactions

liquidity ability to convert assets into cash in order to meet primarily short-term cash needs or emergencies

marketable securities investments that can be converted to cash quickly; short-term liquid securities that can be bought or sold on a public exchange (market) and tend to mature in a year or less

net terms also referred to as the full credit period; the number of days that a business purchaser has before they must pay their invoice

net working capital the difference between current assets and current liabilities (Current Assets – Current Liabilities = Net Working Capital)

operating cycle the time it takes a company to acquire inventory, sell inventory, and collect the cash from the sale of said goods; synonymous with cash cycle

opportunity cost the cost of a forgone opportunity

ordering costs costs associated with placing an order with a vendor or supplier

precautionary motive a reason to hold cash balances for unexpected expenditures such as repairs, costs associated with unexpected breakdown of equipment, and hiring temporary workers to meet unexpected production demands

quick payment a payment made on an account payable during a period of time that falls within the discount period

ratios numerical values taken from financial statements that are used in formulas to examine financial relationships and create metrics of performance, strengths, weaknesses; help analysts gain insight and meaning

speculative motive a reason for holding an amount of cash—to be able to take advantage of investment opportunities

stockout costs an opportunity cost (lost revenue) incurred when a customer order cannot be filled because the item is out of stock and the customer goes elsewhere for the product

supply chain the network of participants and activities between a company and its suppliers and the company and its customers; exists to distribute a product or to provide a service to the final buyer

trade credit credit granted to a business, also called accounts payable; allows a business to buy goods and services on account and pay the cash at some point in the future

transactional motive holding an amount of cash to meet operational expenditures such as payroll, payments to vendors, and loan payments

working capital the resources that are needed to meet the daily, weekly, and monthly operating cash flow needs