What is Communication?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Define communication and describe communication as a process.

- Recognize the importance of communication in better understanding yourself and others.

- Explain why miscommunication sometimes occurs and how your perceptual filters can contribute to this issue.

- Identify and describe the eight essential components of communication.

- Identify and describe two models of communication.

| Communication is “the process by which one person stimulates meaning in the mind of another through a message” (McCroskey, 2016, pp. 20-21). |

Consider the role of communication in your daily life. When you make a phone call, send a text message, or like something on social media, what is the purpose of that activity? Have you ever felt confused by what someone is telling you or argued over a misunderstood email? The underlying issue may be a communication deficiency.

Current models and theories explain, plan, and predict communication processes and their outcomes, including successes and failures. We may be more concerned with practical knowledge and skills in the workplace than with theory. However, good practice is built on a solid foundation of understanding and skill. For this reason, this textbook will help you develop foundational skills in key areas of communication, with a focus on applying theory and providing practice opportunities.

Communication

Communication is key to your success—in relationships, in the workplace, as a citizen of your country, and across your lifetime. Your ability to communicate comes from experience, and experience can be an effective teacher. Still, this text and the related business communication course will offer you a wealth of experiences gathered from professional speakers across their lifetimes. You can learn from their lessons and become a more effective communicator right from the start.

Business communication can be thought of as a problem-solving activity in which individuals may address the following questions:

- What is the situation?

- What are some possible communication strategies?

- What is the best course of action?

- What is the best way to design the chosen message?

- What is the best way to deliver the message?

The Reality: Technical Writing and Communication

When we think of engineers, we tend to think about bridges, planes, buildings, and other engineering marvels. Yet, how do these large-scale projects work without communication? The truth is that engineers spend a great deal of their time communicating:

- How graduate engineers spend their time:

- 25-50% Problem-solving of some kind.

- 50-75% Communicating (Writing and reading reports, letters, memos, proposals, presentations, and discussions with w/colleagues, managers, and clients).

- Performance evaluations and job advancement often depend more on communication skills than technical expertise.

(McConkey, 2017)

This data shows that engineers spend at least half, if not more, of their time on communicative tasks instead of technical problem-solving, which is more commonly associated with the field. The research also found that professionals in more advanced careers, such as those in management positions, spend only 5-10% of their time on problem-solving and 90-95% on related communication tasks.

Think about your career field. How much time do you think you’ll spend verbally and nonverbally communicating? How much time listening? How much time do you spend reading? As we embark on this journey in this book, consider where you want to develop your communication skills for your career field.

Many theories have been proposed to describe, predict, and understand the behaviors and phenomena of communication. Regarding business communication, we are often more interested in practical applications than in theory, as we aim to ensure that our communications yield the desired results. However, it can be valuable to understand what communication is and how it works to achieve results.

Defining Communication

The root of “communication” in Latin is communicare, which means to share or make common (Weekley, 1967). Communication is the process of understanding and sharing meaning (Pearson & Nelson, 2000).

At the center of our communication study is the relationship involving participant interaction. This definition serves us well with its emphasis on understanding and effectively sharing another’s point of view, which we’ll examine in depth throughout this text.

The first keyword in this definition is process. A method is a dynamic activity that is difficult to describe because it is constantly changing (Pearson & Nelson, 2000). Imagine you are alone in your kitchen thinking. Someone you know (say, your mother) enters the kitchen, and you talk briefly. What has changed? Now, imagine that your mother is joined by someone else, someone you haven’t met before—and this stranger listens intently as you speak, almost as if you were giving a speech. What has changed? Your perspective might change, and you might watch your words more closely. Your mother’s and the stranger’s feedback or response (who are, in essence, your audience) may cause you to reevaluate what you are saying. When we interact, all these factors—and many more—influence the communication process.

The second keyword is understanding: “To understand is to perceive, interpret, and relate our perception and interpretation to what we already know” (McLean, 2003). What image comes to mind if a friend tells you a story about falling off a bike? Now your friend points out the window, and you see a motorcycle lying on the ground. Understanding the words and the concepts or objects they refer to is a crucial part of effective communication.

Next comes the word sharing. Sharing means doing something together with one or more people. You may share a joint activity, such as when you share in compiling a report, or you may benefit jointly from a resource, such as when you and several coworkers share a pizza. In communication, sharing occurs when you convey thoughts, feelings, ideas, or insights to others. You can also share with yourself (a process called intrapersonal communication) when you bring ideas to consciousness, ponder how you feel about something, figure out the solution to a problem, and have a classic “Aha!” moment when something becomes clear.

Finally, meaning is what we share through communication. The word “bike” represents both a bicycle and a short name for a motorcycle. By examining the context in which the word is used and asking questions, we can uncover the shared meaning of the word and gain a deeper understanding of the message.

Eight Essential Components of Communication

To better understand the communication process, we can break it down into a series of eight essential components:

-

Source

-

Message

-

Channel

-

Receiver

-

Feedback

-

Environment

-

Context

-

Interference

Each of these eight components serves an integral function in the overall process. Let’s explore them one by one.

Source

The source imagines, creates, and sends the message. In a public speaking situation, the source is the person giving the speech. They convey the message by sharing new information with the audience. The speaker also conveys a message through their tone of voice, body language, and choice of clothing. The speaker begins by determining the message—what to say and how to say it. The second step involves encoding the message by choosing the proper order or the perfect words to convey the intended meaning. The third step is to present or send the information to the receiver or audience. Finally, by watching for the audience’s reaction, the source perceives how well they received the message and responds with clarification or supporting information.

Message

“The message is the stimulus or meaning produced by the source for the receiver or audience” (McLean, 2005). When you plan to give a speech or write a report, your message may seem to be only the words you choose that will convey your meaning. But that is just the beginning. The words are brought together with grammar and organization. You may choose to save your most important point for last. The message also consists of how you say it—in a speech, with your tone of voice, body language, and appearance—and in a report, with your writing style, punctuation, and the headings and formatting you choose. In addition, part of the message may be the environment or context in which you present it, and the noise that might make your message hard to hear or understand. Imagine, for example, that you are addressing a large audience of sales representatives and are aware that a World Series game is scheduled for tonight. Your audience might have difficulty settling down, but you may choose to open with, “I understand there is an important game tonight.” In this way, by expressing verbally something that most people in your audience are aware of and interested in, you might grasp and focus their attention.

Channel

“The channel is how a message or messages travel between source and receiver” (McLean, 2005). For example, think of your television. How many channels do you have on your television? Each channel requires some space, even in a digital world, whether in the cable or in the signal that carries the message of each channel to your home. Television combines an audio signal you hear with a visual signal you see. Together, they convey the message to the receiver or audience. Turn off the volume on your television. Can you still understand what is happening? You can do so because the body language conveys part of the show’s message. Now, turn up the volume, but turn around so you cannot watch the television. You can still hear the dialogue and follow the storyline.

Similarly, you use a channel to convey your message when you speak or write. Spoken channels include face-to-face conversations, speeches, telephone conversations, voice mail messages, radio, public address systems, and voice over Internet protocol (VoIP). Written channels include letters, memoranda, purchase orders, invoices, newspaper and magazine articles, blogs, emails, text messages, tweets, and other similar forms of communication.

Receiver

“The receiver receives the message from the source, analyzing and interpreting the message in ways both intended and unintended by the source” (McLean, 2005). To better understand this component, think of a receiver on a football team. The quarterback throws the football (message) to a receiver, who must see and interpret where to catch the ball. The quarterback may intend for the receiver to “catch” his message in one way, but the receiver may see things differently and miss the football (the intended meaning) altogether.

As a receiver, you listen, see, touch, smell, and/or taste to receive a message. Your audience “sizes you up,” much as you might check them out long before you take the stage or open your mouth. The nonverbal responses of your listeners can serve as clues on how to adjust your opening. By imagining yourself in their place, you anticipate what you would look for if you were them. Just as a quarterback plans where the receiver will be to place the ball correctly, you, too, can recognize the interaction between source and receiver in a business communication context. This happens simultaneously, illustrating why and how communication is constantly changing.

Feedback

You give feedback when you respond to the source, intentionally or unintentionally. Feedback is composed of messages the receiver sends back to the source. Verbal or nonverbal, all these feedback signals allow the source to see how well, or how accurately (or poorly and inaccurately), the message was received. Feedback also allows the receiver or audience to ask for clarification, agree or disagree, or indicate that the source could make the message more engaging. As the amount of feedback increases, the accuracy of communication also increases (Leavitt & Mueller, 1951).

For example, suppose you are a sales manager participating in a conference call with four sales reps. As the source, you want to advise the reps to capitalize on the fact that it is approaching the holiday season, and they should prioritize closing sales on video game merchandise. You state your message, but you hear no replies from your listeners. You might assume that this means they understood and agreed with you, but later in the month, you might be disappointed to find that very few sales were made. If you followed up on your message with a request for feedback (“Does this make sense? Do any of you have any questions?”). You may have an opportunity to clarify your message and determine whether any of the sales representatives believe your suggestion would not be suitable for their customers.

Environment

“The environment is the atmosphere, physical and psychological, where you send and receive messages” (McLean, 2005). The environment can include the tables, chairs, lighting, and sound equipment that are in the room. The room itself is an example of the environment. The environment can also include factors such as formal dress, which may indicate whether a discussion is open and informal or more professional and formal. People may be more likely to have an intimate conversation when they are physically close, and less likely to do so when they can only see each other from a distance. In that case, they may text each other, a form of intimate communication. The environment influences the choice to text. As a speaker, your environment will significantly impact and affect your speech. It’s always a good idea to check out the venue where you’ll be speaking before the day of the actual presentation.

Context

“The context of the communication interaction involves the setting, scene, and expectations of the individuals involved” (McLean, 2005). A professional communication context may involve business suits (environmental cues) that directly or indirectly influence the participants’ language and behavior expectations.

A presentation or discussion does not occur in isolation. When you came to class, you came from somewhere. So did the person seated next to you, as did the instructor. The degree to which the environment is formal or informal depends on the contextual expectations for communication that the participants hold. The person sitting next to you may be used to informal communication with instructors. Still, this particular instructor may be used to verbal and nonverbal displays of respect in the academic environment. You may also be accustomed to formal interactions with instructors and find your classmate’s question, “Hey Teacher, do we have homework today?” rude and inconsiderate when they see it as usual. The nonverbal response from the instructor will certainly give you a clue about how they perceive the interaction, both the word choices and how they were said. Context is all about what people expect from each other, and we often create those expectations out of environmental cues. Traditional gatherings, such as weddings or quinceañeras, are typically formal events. There is a time for quiet social greetings, a time for silence as the bride walks down the aisle, or the father may have the first dance with his daughter as she is transformed from a girl to womanhood in the eyes of her community. There may come a time for rambunctious celebration and dancing in either celebration. You may be called upon to give a toast, and the wedding or quinceañera context will influence your presentation, timing, and effectiveness.

Who speaks first in a business meeting? That probably relates to each person’s position and role outside the meeting. Context plays a vital role in communication, particularly across cultures.

Interference

Interference, also called noise, can come from any source. “Interference is anything that blocks or changes the source’s intended meaning of the message” (McLean, 2005). For example, if you drove a car to work or school, you might be surrounded by noise. Car horns, billboards, or perhaps the radio in your vehicle interrupted your thoughts or your conversation with a passenger. Psychological noise occurs when your thoughts occupy your attention while you are hearing or reading a message. Imagine it is 4:45 p.m. and your boss, who is at a meeting in another city, emails you asking for last month’s sales figures, an analysis of current sales projections, and the sales figures from the same month for the past five years. You may open the e-mail, start to read, and think, “Great—no problem—I have those figures and that analysis right here in my computer.” You reply with last month’s sales figures and the current projections attached. Then, you turn off your computer at five o’clock and go home. The next morning, your boss calls on the phone to tell you they were inconvenienced because you neglected to include the sales figures from the previous years. What was the problem? Interference: Thinking about how you wanted to respond to your boss’s message prevented you from reading attentively enough to understand the whole message.

Interference can also come from other sources. Perhaps you are hungry, and your focus on your current situation interferes with your ability to listen. Maybe the office is hot and stuffy. If you were an audience member listening to an executive speech, how could this impact your listening ability and participation?

Noise interferes with the standard encoding and decoding of the message carried by the channel between the source and the receiver. Not all noise is bad, but it can interfere with the communication process. For example, your cell phone ringtone may be a welcome noise to you, but it may interrupt the communication process in class and bother your classmates.

Communication Can Be Complicated

Getting your point across requires more than simply speaking in front of a crowd or writing words on a page. How we are understood is influenced by the context of the communication and the relational qualities of the person with whom we communicate. In that context, however, it will differ from situation to situation and, most importantly, from person to person.

Exercise: Interactive Video

In the TED Talk below, Hampsten (2016) explains why miscommunication occurs frequently and how we can minimize frustration while expressing ourselves more effectively.

This video is the first of many interactive activities that you will encounter throughout this textbook. It will stop at various points and provide you with questions to check your understanding throughout. The activities are also bookmarked, allowing you to return and try them again.

If the above activity does not work, here is a link to the original video: tinyurl.com/whatiscomm

Now that you’ve watched the video, answer the following questions:

Finally, reflect on the following questions:

- What perceptual filters influence your communication? Can you identify at least three?

- How do these filters affect or influence your interpretation of communication?

Two Models of Communication

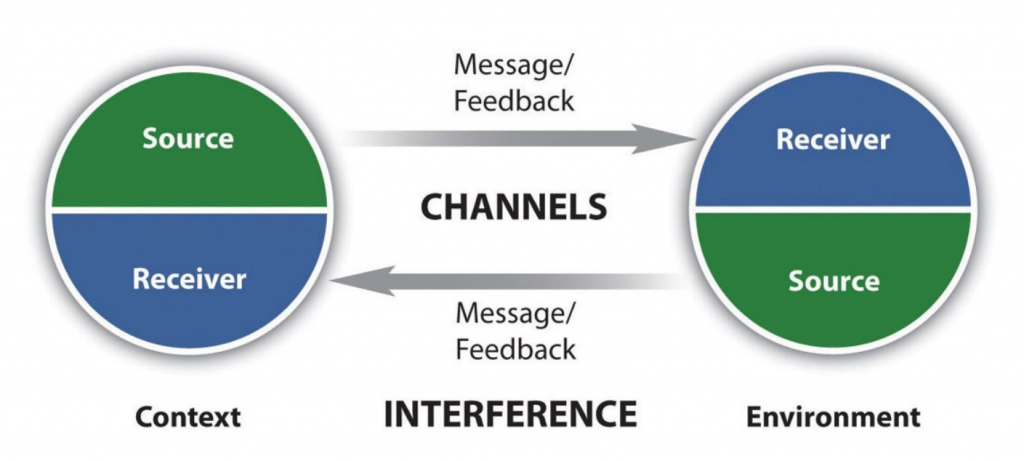

Researchers have observed that when communication occurs, the source and the receiver may send messages simultaneously, often overlapping in time. As the speaker, you will typically play both roles, serving as both source and receiver. You’ll focus on the communication and the reception of your messages to the audience. The audience will respond with feedback that provides important clues. While there are many communication models, we will focus on two here that offer valuable perspectives and lessons for business communicators. Rather than looking at the source sending a message and someone receiving it as two distinct acts, researchers often view communication as transactional (Figure 1.1 “Transactional Model of Communication”), with actions frequently happening simultaneously.

The distinction between source and receiver is blurred in conversational turn-taking, where participants play both roles simultaneously.

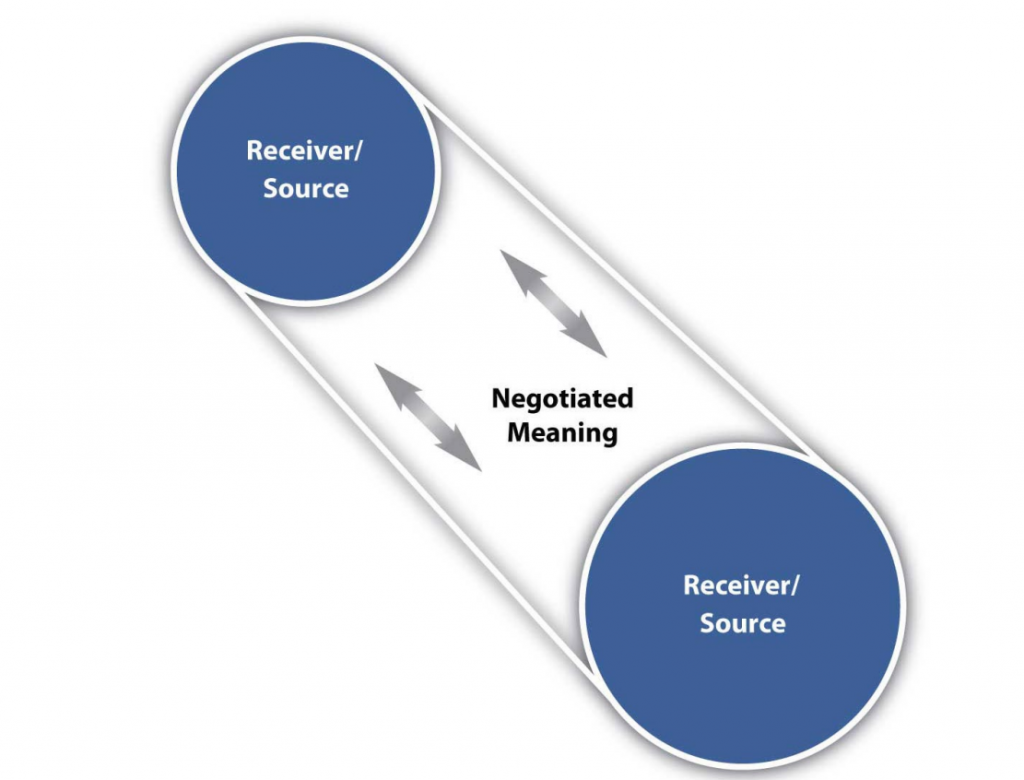

Researchers have also explored the notion that we all construct our interpretations of the message. As the State Department quote at the beginning of this chapter indicates, what I said and what you heard may be different. In the constructivist model (Figure 1.2 “Constructivist Model of Communication”), we focus on the negotiated meaning, or common ground, when trying to describe communication (Pearce & Cronen,

1980).

Imagine that you are visiting Atlanta, Georgia, and go to a restaurant for dinner. When asked if you want a “Coke,” you may reply, “Sure.” The waiter may ask you again, “What kind?” and you may reply, “Coke is fine.” The waiter may ask a third time, “What kind of soft drink would you like?” The misunderstanding in this example is that in Atlanta, the home of the Coca-Cola Company, most soft drinks are generically referred to as “Coke.” When ordering a soft drink, please specify the type, even if you wish to order a beverage that is not a cola or made by the Coca-Cola Company. To someone from another region of the United States, the words “pop,” “soda pop,” or “soda” may be familiar as a general term for a soft drink, but not necessarily the brand “Coke.” In this example, you and the waiter understand the word “Coke,” but each of you understands it to mean something different. To communicate effectively, you must each understand what the term means to the other person and establish common ground to comprehend the request and provide a complete answer.

Because we carry multiple meanings of words, gestures, and ideas within us, we can use a dictionary to guide us, but we will still need to negotiate their meanings.

Key Takeaways

- The communication process involves understanding, sharing, and meaning, and it consists of eight essential elements: source, message, channel, receiver, feedback, environment, context, and interference.

- Among the models of communication are the transactional process, in which actions happen simultaneously, and

The constructivist model focuses on shared meaning.

References

Businesstopia. (2018, February 15). Transactional model of communication. https://www.businesstopia.net/communication/transactional-model-communication

Hampsten, K. (2016, Feb 26). How miscommunication happens (and how to avoid it). [YouTube]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gCfzeONu3Mo

Hyman, B. I. (2002). Chapter 2: Problem formulation. In Fundamentals of engineering design. Prentice Hall.

Leavitt, H., & Mueller, R. (1951). Some effects of feedback on communication. Human Relations, 4, 401–410.

McConkey, S. (2017, March 17). Writing a term report [ENGR 120 Plenary Lecture]. University of Victoria.

McCroskey, J. C. (2016). An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication: A Western Rhetorical Perspective. Pearson Education.

McLean, S. (2003). The basics of speech communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication (p. 10). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon

Pearce, W. B., & Cronen, V. (1980). Communication, action, and meaning: The creating of social realities. New York, NY: Praeger.

Pearson, J., & Nelson, P. (2000). An introduction to human communication: Understanding and sharing (p.6). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Swarts, J., Pigg, S., Larsen, J., Helo Gonzalez, J., De Haas, R., & Wagner, E. (2018). Communication in the workplace: What can NC state students expect? Professional Writing Program, North Carolina State University. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1pMpVbDRWIN6HssQQQ4MeQ6U-oB-sGUrtRswD7feuRB0/edit#

This chapter is adapted from Technical Writing Essentials by Suzan Last (on BCcampus) and “Business Communication for Success“, which are both licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

the process of one person stimulating meaning in the mind of another by means of a message

a dynamic activity that is hard to describe because it changes

to perceive, interpret, and relate our perception and interpretation to what we already know

doing something together with one or more people

what we share through communication

the person forming and delivering the message

the stimulus or meaning produced by the source for the receiver or audience

how a message or messages travel between source and receiver

a person who receives a message from a sender

information that a receiver sends back to the sender

the atmosphere, physical and psychological, where you send and receive messages

involves the setting, scene, and expectations of the individuals involved

is anything that blocks or changes the source’s intended meaning of the message

information that is added unintentionally to a message during a transmission

types of communication that are highly designed to create a purposeful exchange between the sender and receiver of a message

focusing on the negotiated meaning, or common ground, when trying to describe communication