Theories of Leadership

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe various theories of leadership.

- Understand Theory X and Theory Y Leaders.

- Explore the trait, behavioral, contingency, and transformational/transactional approaches to leadership.

- Explain the Managerial Grid.

Not all leaders lead in the same way, and not all situations require the same type of leadership. Over the years, scholars and practitioners have developed several theories to help explain what makes someone a strong leader, how leadership works in different settings, and why some approaches succeed while others fail. This section will explore key leadership theories, ranging from early ideas about personality traits to more modern views that emphasize adaptability, motivation, and relationships. You’ll learn about Theory X and Theory Y, which reflect different assumptions about people’s work and traits, behavioral, contingency, and transformational/transactional approaches. We’ll also introduce the Managerial Grid, a tool that helps map out leadership styles based on concern for people and concern for tasks.

By understanding these theories, you’ll be better equipped to recognize leadership in action and perhaps even reflect on your leadership style.

Theory X and Theory Y Leaders

McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y posit two different sets of attitudes about the individual as an organizational member (McGregor, 1957; McGregor, 1960). Theory X and Y thinking give rise to two different styles of leadership. The Theory X leader assumes that the average individual dislikes work and cannot exercise adequate self-direction and self-control. As a consequence, they exert a highly controlling leadership style. In contrast, Theory Y leaders believe that people have creative capacities and the ability and desire to exercise self-direction and self-control. They typically allow organizational members significant discretion in their jobs and encourage them to participate in departmental and managerial decision-making. Theory Y leaders are more likely to adopt involvement-oriented approaches to leadership and design organizations organically for their leadership group.

Trait Approaches to Leadership

The earliest approach to studying leadership sought to identify traits that distinguished leaders from non-leaders. What were the personality characteristics and the physical and psychological attributes of people who are viewed as leaders? Different studies employed various measures due to time constraints in assessing personality traits. By 1940, researchers concluded that the search for leadership-defining traits was futile. In recent years, however, following advances in personality literature, such as the development of the Big Five personality framework, researchers have had greater success in identifying traits that predict leadership (House & Aditya, 1997). Most importantly, among the contemporary approaches to leadership, charismatic leadership may be viewed as an example of a trait approach. The traits that show relatively strong relations with leadership are discussed below (Judge et al., 2002).

Intelligence

General mental ability, which psychologists refer to as “g” and “IQ” in everyday language, has been linked to a person’s emergence as a leader within a group. Specifically, people with high mental abilities are more likely to be viewed as leaders in their environment (House & Aditya, 1997; Ilies et al., 2004; Lord et al., 1986; Taggar et al., 1999). We should caution that intelligence is a positive but modest predictor of leadership. When actual intelligence is measured using paper-and-pencil tests, its relationship to leadership is somewhat weaker than when intelligence is defined as the perceived intelligence of a leader (Judge et al., 2004). In addition to possessing a high IQ, effective leaders often exhibit high emotional intelligence (EQ). The psychologist who coined the term “emotional intelligence,” Daniel Goleman, believes that IQ is a threshold quality: it matters for entry into high-level management jobs. However, once you get there, it no longer helps leaders because most leaders already have a high IQ. According to Goleman, what differentiates effective leaders from ineffective ones is their ability to control and understand other people’s emotions, internal motivation, and social skills (Goleman, 2004).

| Trait | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Openness | Being curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. |

| Conscientiousness | Being organized, systematic, punctual, achievement-oriented, and dependable. |

| Extraversion | Being outgoing, talkative, sociable, and enjoying social situations. |

| Agreeableness | Being affable, tolerant, sensitive, trusting, kind, and warm. |

| Neuroticism | Being anxious, irritable, temperamental, and moody. |

| Source: Organizational Behaviour | |

Psychologists have proposed various systems for categorizing the characteristics that make up an individual’s unique personality; one of the most widely accepted is the “Big Five” model, which rates an individual according to Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Several Big Five personality traits have been linked to leadership emergence (i.e., whether someone is perceived as a leader by others) and effectiveness (Judge et al., 2002). For example, extraversion is related to leadership. Extraverts are sociable, assertive, and energetic people. They enjoy interacting with others in their environment and demonstrate self-confidence. They emerge as leaders in various situations because they are dominant and social in their environment. Out of all personality traits, extraversion has the strongest relationship with leader emergence and effectiveness. This is not to say that all effective leaders are extraverts, but you are more likely to find extraverts in leadership positions. Research shows that another personality trait related to leadership is conscientiousness. Conscientious people are organized, take initiative, and demonstrate persistence in their endeavors. Conscientious individuals are more likely to emerge as leaders and be effective in their roles. Finally, people who have openness to experience—those who demonstrate originality, creativity, and are open to trying new things—tend to emerge as leaders and be quite effective.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is not one of the Big Five personality traits, but an essential aspect of one’s personality. The degree to which a person is at peace with oneself and has an overall positive assessment of one’s self-worth and capabilities seems relevant to whether someone is viewed as a leader. Leaders with high self-esteem tend to support their subordinates more, and when punishment is administered, they do so more effectively (Atwater et al., 1998; Niebuhr, 1984). Individuals with high self-esteem may exhibit greater levels of self-confidence, which in turn affects their image in the eyes of their followers. Self-esteem may also explain the relationship between some physical attributes and leader emergence. For example, research shows a strong relationship between being tall and being viewed as a leader (as well as one’s career success over life). It is proposed that self-esteem may be the key mechanism linking height to being viewed as a leader, because taller people are also found to have higher self-esteem and, therefore, may project greater levels of charisma and confidence to their followers (Judge & Cable, 2004).

Integrity

Research also indicates that effective leaders possess a moral compass and consistently demonstrate honesty and integrity (Reave, 2005). Leaders whose integrity is questioned lose their trustworthiness and hurt their company’s business. Some traits are also negatively related to leader emergence and success in that position. For example, agreeable people who are modest, good-natured, and avoid conflict are less likely to be perceived as leaders (Judge et al., 2002). Despite problems in trait approaches, these findings can still be helpful to managers and companies. For example, understanding leadership traits helps organizations select the right individuals for positions of responsibility. The key to benefiting from the findings of trait researchers is to be aware that not all traits are equally effective in predicting leadership potential across all circumstances. Some organizational situations allow leader traits to make a greater difference (House & Aditya, 1997). For example, leaders’ traits may significantly impact their leadership potential in small, entrepreneurial organizations, where leaders have considerable leeway in determining their behavior. In large, bureaucratic, and rule-bound organizations such as the government and the military, a leader’s traits may have less to do with how the person behaves and whether the person is a successful leader (Judge et al., 2002). Moreover, some traits become relevant in specific circumstances. For example, bravery is likely a key characteristic in military leaders, but not necessarily in business leaders. Scholars now conclude that instead of identifying a few traits that distinguish leaders from non-leaders, it is essential to determine the conditions under which different traits affect a leader’s performance and whether a person emerges as a leader (Hackman & Wageman, 2007).

Exercise

- Which best describes your leadership approach: Theory X or Theory Y?

- Think of a leader you admire. What traits does this persona have? Are they consistent with the characteristics discussed in this chapter? If not, why is this person effective despite different characteristics?

Behavioural Approaches to Leadership

When trait researchers became disillusioned in the 1940s, they shifted their focus to studying leader behaviors. What did effective leaders do? Which behaviors made them perceived as leaders? Which behaviors increased their success? To answer these questions, researchers at Ohio State University and the University of Michigan employed various techniques, including observing and surveying leaders in laboratory settings. This research stream led to the discovery of two broad categories of behaviors: task-oriented and people-oriented behaviors. That is to say, the extent to which a leader is focused on the task at hand compared to the relationships. At the time, researchers believed that these two categories of behaviors were the keys to the leadership puzzle (House & Aditya, 1997). When examining the overall findings regarding these leadership behaviors, it appears that both types of behaviors, in aggregate, are beneficial to organizations, but for different purposes. For example, when leaders exhibit people-oriented behaviors, employees tend to be more satisfied and react positively. However, when leaders are task-oriented, productivity tends to be higher (Judge et al., 2004). Moreover, the situation in which these behaviors are demonstrated seems to matter. Task-oriented behaviors were more effective in small and large companies (Miles & Petty, 1977). There is also evidence that very high levels of leader task-oriented behaviors may cause burnout in employees (Seltzer & Numerof, 1988).

Contingency Approaches to Leadership

What is the best leadership style? You must have realized by now that this may not be the right question. Instead, a better question might be: under which conditions are certain leadership styles more effective? After the disappointing results of trait and behavioural approaches, several scholars developed leadership theories that specifically incorporated the role of the environment. Specifically, researchers adopted a contingency approach to leadership—rather than trying to identify traits or behaviors that would be effective under all conditions, attention shifted toward specifying the situations under which different styles would be effective. One of the earliest, best-known, and most controversial situation-contingent leadership theories was developed by Fred E. Fiedler at the University of Washington. This theory is known as the contingency theory of leadership. According to Fiedler, organizations attempting to achieve group effectiveness through leadership must assess the leader in terms of an underlying trait, evaluate the situation faced by the leader, and construct a proper match between the two. This section will discuss two alternate contingency theories: Situational Leadership and Path-goal Theory.

Situational Leadership

Kenneth Blanchard and Paul Hersey’s Situational Leadership Theory (SLT) posits that leaders should employ varying leadership styles based on their followers’ developmental level (Hersey et al., 2007). According to this model, employee readiness (a combination of competence and commitment levels) is the key factor determining the proper leadership style. This approach has been highly popular, with 14 million managers across 42 countries undergoing SLT training, and 70% of Fortune 500 companies employing it. The model summarizes the directive and supportive behaviours leaders may exhibit. The model argues that to be effective, leaders must use the right behavior style at the right time in each employee’s development. It is recognized that followers are key to a leader’s success. Employees are seen as highly committed but with low competence at the earliest stages of development. Thus, leaders should be highly directive and less supportive. The leader should engage in more coaching behaviours as the employee becomes more competent. Supportive behaviors are recommended once the employee has reached moderate to high levels of competence. And finally, delegating is recommended for leaders dealing with highly committed and competent employees. While the SLT is popular among managers, relatively easy to understand and use, and has endured for decades, research on its basic assumptions has provided mixed support (Blank et al., 1990; Graeff, 1983; Fernandez & Vecchio, 2002). Therefore, while it can be helpful to consider matching behaviors to situations, overreliance on this model, excluding others, is premature.

| Follower Readiness Level | Competence (Low) | Competence (Low) | Competence (Moderate to High) | Competence (High) |

| Commitment (High) | Commitment (Low) | Commitment (Variable) | Commitment (High) | |

| Recommended Leader Style | Directing Behaviour | Coaching Behaviour | Supporting Behaviour | Delegating Behaviour |

Situational Leadership Theory enables leaders to match their style to the readiness levels of their followers.

Path-Goal Theory of Leadership

Robert House’s path-goal theory of leadership is based on the expectancy theory of motivation (House, 1971). The expectancy theory of motivation suggests that employees are motivated when they believe—or expect—that (a) their effort will lead to high performance, (b) their high performance will be rewarded, and (c) the rewards they will receive are valuable to them. According to the path-goal theory of leadership, the leader’s main job is to make sure that all three of these conditions exist. Thus, leaders will create satisfied and high-performing employees by ensuring that employee effort leads to effective performance, and their performance is rewarded with the desired outcomes. The leader removes roadblocks and creates an environment that motivates subordinates. The theory also makes specific predictions about the type of leader behavior that will be effective under certain circumstances (House, 1996; House & Mitchell, 1974). The theory identifies four leadership styles. Each of these styles can be effective, depending on the characteristics of employees (such as their ability level, preferences, locus of control, and achievement motivation) and characteristics of the work environment (such as the level of role ambiguity, the degree of stress present in the environment, and the degree to which the tasks are unpleasant).

Four Leadership Styles

Directive leaders provide specific directions to their employees. They lead employees by clarifying role expectations, setting schedules, and ensuring they know what to do on a given work day. The theory predicts that the directive style will work well when employees are experiencing role ambiguity on the job. If people are unclear about how to perform their jobs, providing them with specific directions will motivate them. On the other hand, if employees already have role clarity and perform dull, routine, and highly structured jobs, giving them direction does not help. It may hurt them by creating an even more restrictive atmosphere. Directive leadership is also considered less effective when employees have high ability levels. When managing professional employees with high levels of expertise and job-specific knowledge, telling them what to do may create a low-empowerment environment and impair motivation.

Supportive leaders provide emotional support to employees. They treat employees well, care about them, and are encouraging. Supportive leadership is predicted to be effective when employees are under stress or performing tedious, repetitive tasks. When employees know exactly how to perform their jobs but find them unpleasant, supportive leadership may be more effective in motivating them. Participative leaders ensure that employees are involved in making important decisions. This approach may be more effective when employees have high levels of ability and the decisions are personally relevant to them. For employees with a high internal locus of control (those who believe they control their destiny), participative leadership is a way to indirectly influence organizational decisions, which is likely to be appreciated. Achievement-oriented leaders set goals for their employees and encourage them to strive for and achieve these goals. Their style challenges employees and focuses their attention on work-related goals. This style is likely effective when employees have high levels of ability and achievement motivation. Researchers have partially supported the path-goal theory of leadership, albeit encouragingly. The theory’s most significant contribution may be that it highlights the importance of a leader’s ability to adapt their style according to the circumstances. Unlike Fiedler’s contingency theory, in which the leader’s style is assumed to be fixed and only the environment can be changed, House’s path-goal theory underlines the importance of varying one’s style depending on the situation.

Source: Predictions of the Path-Goal Theory Approach to Leadership. Sources: Based on information presented in House, R. J. (1996) and House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1974).

Relational Approach

The next approach to leadership is known as the relational approach, as it focuses not on the traits, characteristics, or functions of leaders and followers, but on the types of relationships that develop between them. To help us understand the relational approach to leadership, let’s examine two perspectives: Robert Blake and Jane Mouton’s Managerial Grid and George Graen’s Leader-Member Exchange Theory.

Robert Blake & Jane Mounton’s Managerial Grid

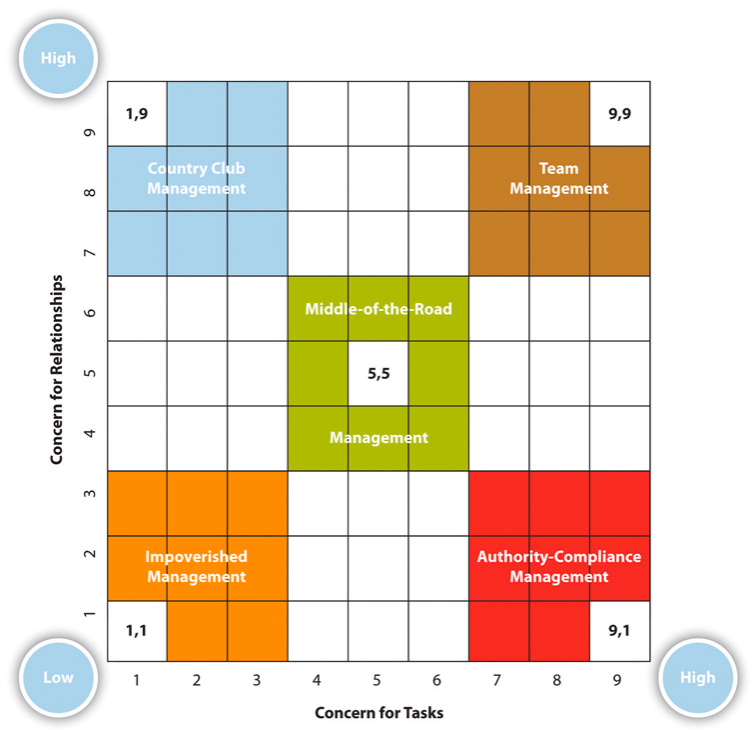

The first major relational approach we will discuss is Blake and Mounton’s (1964) Managerial Grid. While the grid is referred to as a “management” grid, the subtitle clarifies that it serves as a tool for effective leadership and management. In the original grid created in 1965, the two researchers were concerned with whether a leader was involved with their followers or production. In the version we’ve recreated for you in Figure 6.3, we’ve relabeled the two as concerns for relationships and tasks to maintain consistency with other leadership theories discussed in this chapter. The basic idea is that there are nine steps on each line of the axis (x-axis refers to task-focused leadership; y-axis refers to relationship-focused leadership). An individual leader’s focus on relationships and tasks will determine where they fall on the Managerial Grid as a leader. We have five basic management styles: impoverished, authority compliance, country club, team, and middle-of-the-road. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Impoverished Management

A leader’s basic approach under the impoverished management style is completely hands-off. This leader assigns someone to a job or task and then expects it to be accomplished without any oversight. In Blake and Mouton’s (2011) words, “the person managing 1,1 has learned to ‘be out of it,’ while remaining in the organization… [this manager’s] imprint is like a shadow on the sand. It passes over the ground, but leaves no permanent mark” (p. 315-316).

Authority-Compliance Management

The second leader coordinates at the 9,1 level in the leadership grid. The authority-compliance management style has a high concern for tasks but a low concern for establishing or fostering relationships with its followers. Consider this leader the closest to Frederick Taylor’s scientific management style of leadership. The leader makes all the decisions and then dictates to their followers. Furthermore, this type of leader will likely micromanage or closely oversee and criticize followers as they accomplish the tasks.

Country Club Management

The third type of manager is known as the country club management style, which is the polar opposite of the authority-compliance manager. In this case, the manager is almost entirely concerned with establishing or fostering relationships with their followers. Still, the task(s) needing to be accomplished disappear into the background. When assigning tasks, this leader empowers their followers and believes that they will perform the task well without any oversight. This type of leader also adheres to Thumper’s advice from the classic Disney movie Bambi: “If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all.”

Team Management

The next leadership style is at the high end of concern for both task and relationships, which is referred to as the team management style. This type of leader realizes that “effective integration of people with production is possible by involving them and their ideas in determining the conditions and strategies of work. The needs of people to think, apply mental effort in productive work, and establish sound and mature relationships with one another are utilized to accomplish organizational requirements” (Blake & Mouton, 2011, p. 317). Under this type of management, leaders strive to create environments that promote creativity, task accomplishment, and employee morale and motivation.

Middle-of-the-Road Management

The final form of management discussed by Blake and Mouton was what has been deemed the middle-of-the-road management style. The reasoning behind this management style is the assumption that “people are practical, they realize some effort will have to be exerted on the job. Also, by yielding some push for production and considering attitudes and feelings, people accept the situation and more or less ‘satisfied’ [emphasis in original]” (Blake & Mouton, 2011, p. 316). In the day-to-day practicality of this approach, these leaders believe that any extreme is unrealistic, so finding a middle balance is ideal. If and when an imbalance occurs, these leaders seek ways to rectify it and restore a state of moderation.

George Graen’s Leader-Member Exchange Theory

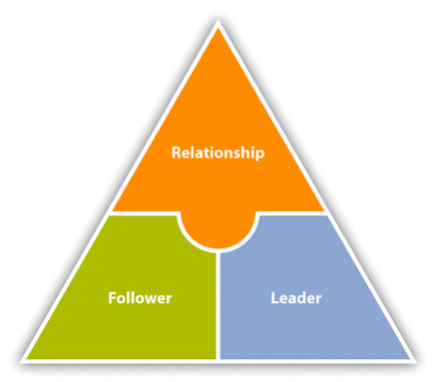

Starting in the mid-1970s, George Graen proposed a different type of theory for understanding leadership. Graen’s (1995) theory of leadership proposed that leadership must be understood as existing in three distinct domains: follower, leader, and relationship (Figure 6.4). The basic idea is that leaders and followers exist within a dyadic relationship; therefore, understanding leadership requires examining the nature of that relationship.

When examining the leader-member exchange (LMX) relationship, it is essential to recognize that leaders have limited social, personal, and organizational resources. Therefore, leaders must be selective in how they allocate these resources to their followers. Ideally, every follower would have the same exchange relationship with their leader. Still, for various reasons, some followers receive more resources from a leader, while others receive fewer resources. Ultimately, high-quality LMX relationships are those “characterized by greater input in decisions, mutual support, informal influence, trust, and greater negotiating latitude;” whereas, low-quality LMX relationships “are characterized by less support, more formal supervision, little or no involvement in decisions, and less trust and attention from the leader” (Lussier & Achua, 2007), p. 254). Whether an individual follower is in a high-quality or low-quality LMX relationship has a significant impact on their view of the organization. Followers in high-quality LMX relationships (also referred to as in-groups) have higher perceptions of leader credibility and a greater regard for their leaders than followers in low-quality LMX relationships (also referred to as out-groups). Not only does the nature of the relationship impact a follower’s perceptions of their leader, but research has also shown that high-LMX relationships lead to greater productivity, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Gagnon & Michael, 2004). Overall, research has shown many positive benefits for followers who have high-LMX relationships, including:

- More productive (produces higher quality and quantity of work);

- Greater levels of job satisfaction;

- Higher levels of employee motivation;

- Greater satisfaction with the immediate supervisor;

- Greater organizational commitment;

- Lower voluntary and involuntary turnover levels;

- Greater organizational participation;

- Greater satisfaction with the communication practices of the organization;

- A clearer understanding of her or his role within the organization;

- Greater exhibition of organizational citizenship behaviors;

- Greater long-term success in one’s career;

- Greater organizational commitment;

- Receive more desirable work assignments; and

- Receive more attention and support from organizational leaders.

One big question in the leadership literature is “How do leaders select followers to enter into a high-LMX relationship?” One possible explanation for why leaders choose some followers and not others for high-LMX relationships stems from the follower’s communication style. In a 2007 study, researchers examined the relationship between follower communication and whether they perceived themselves as in a high-LMX relationship with their immediate supervisor (Madlock, Martin, Bogdan, & Ervin, 2007). Not surprisingly, individuals who reported higher levels of assertiveness, responsiveness, friendliness, cognitive flexibility, attentiveness, and a generally relaxed nature were more likely to report having a high-LMX relationship. One variable that was negatively related to the likelihood of having a high-LMX relationship was a follower’s level of communication apprehension.

Transformational and Transactional Theories of Leadership

Transformational leadership theory is a recent addition to the literature, but more research has been conducted on this theory than all the contingency theories combined. The theory distinguishes transformational and transactional leaders. Transformational leaders lead employees by aligning employee goals with the leader’s goals. Thus, employees working for transformational leaders tend to focus on the company’s well-being rather than their own interests. On the other hand, transactional leaders ensure that employees demonstrate the right behaviours and provide resources in exchange (Bass, 1985; Burns, 1978). Transformational leaders possess four key tools that they utilize to influence employees and foster a commitment to company goals (Bass, 1985; Burns, 1978; Bycio et al., 1995; Judge & Piccolo, 2004). First, transformational leaders are charismatic. Charisma refers to behaviours leaders demonstrate that create confidence in, commitment to, and admiration for the leader (Shamir et al., 1993). Charismatic individuals have a “magnetic” personality that is appealing to followers.

Second, transformational leaders use inspirational motivation, or develop a vision that inspires others. Third is intellectual stimulation, which involves challenging organizational norms and the status quo, encouraging employees to think creatively and work harder. Finally, they employ individualized consideration, which entails demonstrating personal care and concern for the well-being of their followers. While transformational leaders rely on their charisma, persuasiveness, and personal appeal to change and inspire their organizations, transactional leaders employ three distinct methods. Contingent rewards refer to the practice of rewarding employees for their accomplishments. Active management by exception involves allowing employees to perform their jobs without interference while proactively identifying and preventing potential problems before they occur. Passive management by exception is similar in that it consists in leaving employees alone, but in this method, the manager waits until something goes wrong before coming to the rescue.

Research shows that transformational leadership influences leader effectiveness and employee satisfaction (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). Transformational leaders increase their followers’ intrinsic motivation, build more effective relationships with employees, increase their followers’ performance and creativity, increase team performance, and create higher levels of commitment to organizational change efforts (Herold et al., 2008; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Schaubroeck et al., 2007; Shin & Zhou, 2003; Wang et al., 2005). However, except for passive management by exception, transactional leadership styles are also effective and positively influence leader performance and employee attitudes (Judge & Piccolo, 2004). To maximize their effectiveness, leaders must demonstrate both transformational and transactional styles. They should also monitor themselves to avoid demonstrating passive management by exception or leaving employees to their devices until problems arise.

The key factor may be trust. Trust is the belief that leaders will show integrity, fairness, and predictability in their dealings with others. Research shows that when leaders demonstrate transformational leadership behaviours, followers are more likely to trust the leader. The tendency to trust in transactional leaders is substantially lower. Because transformational leaders express greater concern for people’s well-being and appeal to people’s values, followers are more likely to believe that the leader has a trustworthy character (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002).

Servant Leadership

The early 21st century was marked by a series of highly publicized corporate ethics scandals. Between 2000 and 2003, we witnessed a series of scandals involving Enron, WorldCom, Arthur Andersen LLP, Qwest Communications International Inc., and Global Crossing Ltd. As corporate ethics scandals erode investor confidence in corporations and their leaders, the importance of ethical leadership and considering the long-term interests of stakeholders is gaining increasing recognition. Servant leadership is a leadership approach that defines the leader’s role as serving the needs of others. According to this approach, the primary mission of the leader is to develop employees and help them reach their goals. Servant leaders put their employees first, understand their needs and desires, empower them, and help them grow in their careers. Unlike mainstream management approaches, the overriding objective in servant leadership is not limited to getting employees to contribute to organizational goals; rather, it is to empower them to do so. Instead, servant leaders feel a sense of obligation to their employees, customers, and the broader external community.

Employee happiness is often viewed as an end in itself, and servant leaders may sometimes sacrifice their well-being to help employees succeed. In addition to having a clear focus on a moral compass, servant leaders are also committed to serving the community. In other words, their efforts to help others are not restricted to company insiders, and they are genuinely concerned about the broader community surrounding their organization (Greenleaf, 1977; Liden et al., 2008). Even though servant leadership overlaps with other leadership approaches, such as transformational leadership, its explicit focus on ethics, community development, and self-sacrifice is a distinct characteristic of this leadership style. Research indicates that servant leadership has a positive impact on employee commitment, community citizenship behaviors (such as volunteering), and job performance (Liden et al., 2008). Leaders who follow the servant leadership approach create a climate of fairness in their departments, which leads to higher levels of interpersonal helping behaviour (Ehrhart, 2004).

Authentic Leadership

Leaders have to be many things to many people. They operate within different structures, work with others, and must be adaptable to changing circumstances. At times, it may seem that a leader’s most brilliant strategy would be to act as a social chameleon, adapting their style whenever it seems advantageous. However, this would overlook the fact that effective leaders must remain true to themselves. The authentic leadership approach embraces this value: Its key advice is “be yourself.” Think about it: we all have different backgrounds, life experiences, and role models. These trigger events throughout our lifetime shape our values, preferences, and priorities. Instead of trying to fit into societal expectations about what a leader should be, act like, or look like, authentic leaders derive their strength from their past experiences. Thus, one key characteristic of authentic leaders is that they are self-aware. They are introspective, understand their origin, and thoroughly understand their values and priorities. Secondly, they are not afraid to be themselves. In other words, they have high levels of personal integrity. They say what they think. They behave in a way consistent with their values. As a result, they remain true to themselves.

Instead of trying to imitate other great leaders, they find their style in their personality and life experiences (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Gardner et al., 2005; George, 2007; Ilies et al., 2005; Sparrowe, 2005). Authentic leadership requires understanding oneself. Therefore, in addition to self-reflection, feedback from others is needed to understand one’s behaviour and its impact on others. Authentic leadership is viewed as potentially influential because employees are more likely to trust such a leader. Moreover, working for a genuine leader is expected to lead to greater employee satisfaction, performance, and overall well-being (Walumbwa et al., 2008).

Key Takeaways

In this section, we reviewed several influential leadership theories.

- Theory X and Theory Y leaders hold different fundamental assumptions about the nature of employees and their motivations in the workplace.

- Trait approaches identify the characteristics required to be perceived as a leader and succeed.

- Intelligence, extraversion, conscientiousness, openness to experience, and integrity seem to be leadership traits.

- Behavioural approaches identify the types of behaviours leaders demonstrate.

- Both trait and behavioural approaches ignored the context in which leadership occurs, which led to the development of contingency approaches.

- Recently, ethics have become a central focus of leadership theories, including servant leadership and authentic leadership. It appears that being aware of one’s style and ensuring that leaders demonstrate behaviors that address employee, organizational, and stakeholder needs are essential and require flexibility on the part of leaders.

References

Barnard, C. I. (1938). The functions of the executive. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bass, B. M. (1985a). Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13(3), 26-40.

Bass, B. M. (1985b). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York, NY: Free Press.

Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Bass, B.M. (1998). Transformational leadership: Industrial, military, and educational impact. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Benne, K. D., & Sheats, P. (2007). Functional roles of group members. Group Facilitation: A Research & Applications Journal, 8, 30-35. (Reprinted from the Journal of Social Issues, 4, 41-49).

Blake, R., & Mouton, J. (1964). The managerial grid: The key to leadership excellence. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing.

Blake, R., & Mouton, J. (2011). The managerial grid. In W. E. Natemeyer & P. Hersey (Eds.), Classics of Organizational Behavior (4 ed., pp. 308-322). (Reprinted from The managerial grid: The key to leadership excellence. Houston, TX: Gulf Coast).

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

de Vries, R. E., Bakker-Pieper, A., & Oostenveld, W. (2010). Leadership = communication? The relations of leaders’ communication styles with leadership styles, knowledge sharing and leadership outcomes. Journal of Business Psychology, 25, 367-380.

Dinh, J. E., & Lord, R. G. (2012). Implications of dispositional and process views of traits for individual difference research in leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 23(4), 651-669.

Downton, J. V. (1973). Rebel leadership: Commitment and charisma in the revolutionary process. New York, NY: Free Press.

Fiedler, F. E. (1967) A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gagnon, M. A., & Michael, J. H. (2004). Outcomes of perceived supervisor support for wood production employees. Forest Products Journal, 54, 172-178.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219-247.

Hackman, M. S., & Johnson, C. E. (2009). Leadership: A communication perspective (5 ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training and Development Journal, 23(5), 26–34.

Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., & Johnson, D. E. (2000). Management of organizational behavior: Leading human resources (8th ed.). Upper Saddle, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Infante, D. A., & Rancer, A. S. (1982). A conceptualization and measure of argumentativeness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46, 72-80.

Infante, D. A., & Wigley, C.J. (1986). Verbal aggressiveness: An interpersonal model and measure. Communication Monographs, 53, 61-69.

Limon, M. S., & La France, B. H. (2005). Communication traits and leadership emergence: Examining the impact of argumentativeness, communication apprehension, and verbal aggressiveness in work groups. Communication Quarterly, 70, 123-133.

Lowe, K. B., & Gardner, W. L. (2001). Ten years of the Leadership Quarterly: Contributions and challenges for the future. Leadership Quarterly, 11, 459-514.

Lussier, R. N., & Achua, C. F. (2007). Leadership: Theory, application, skill development (3 ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson/South-Western.

Kirkpatrick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (1991). Leadership: Do traits matter? The Executive, 5, 48-60.

Madlock, P. E., Martin, M. M., Bogdan, L., & Ervin, M. (2007). The impact of communication traits on leader-member exchange. Human Communication, 10, 451-464.

Mann, R. D. (1959). A review of the relationship between personality and performance in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 241-270.

McCroskey, J. C. (1984). The communication apprehensive perspective. In J. A. Daly & J. C. McCroskey (Eds.), Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension (pp. 13-38). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Northhouse, P. G. (2007). Leadership: Theory and practice (4 ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; pg. 176.

Shane, S. (2010). Born entrepreneurs, born leaders: How your genes affect your work life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Stogdill, R. M. (1948). Personal factors associated with leadership: A survey of the literature. Journal of Psychology, 25, 35-71.

Wrench, J. S. (2013). How strategic workplace communication can save your organization. In J. S. Wrench (Ed.), Workplace communication for the 21st century: Tools and strategies that impact the bottom line: Vol. 2. External workplace communication (pp. 1-37). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Zaccaro, S. J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 6-16.

Attribution

Organizational Communication Copyright © by Dr. Sarah Hollingsworth is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

assumes that the average individual dislikes work and lacks the ability to exercise adequate self-direction and self-control.

believe that people have creative capacities and the ability and desire to exercise self-direction and self-control.

personality characteristics and the physical and psychological attributes of people who are viewed as leaders

sociable, assertive, and energetic people.

are organized, take initiative, and demonstrate persistence in their endeavors.

those who demonstrate originality, creativity, and are open to trying new things—tend to emerge as leaders and be quite effective.

the overall sense of one's own value and worth.

possess a moral compass and consistently demonstrate honesty

the extent to which a leader is focused on the task at hand compared to the relationships.

to achieve group effectiveness through leadership must assess the leader in terms of an underlying trait, evaluate the situation faced by the leader, and construct a proper match between the two.

posits that leaders should employ varying leadership styles based on their followers' developmental level.

Based on the expectancy theory of motivation. The expectancy theory of motivation suggests that employees are motivated when they believe—or expect—that (a) their effort will lead to high performance, (b) their high performance will be rewarded, and (c) the rewards they will receive are valuable to them.

provide specific directions to their employees.

provide emotional support to employees.

ensure that employees are involved in making important decisions.

set goals for their employees and encourage them to strive for and achieve these goals.

The basic idea is that there are nine steps on each line of the axis (x-axis refers to task-focused leadership; y-axis refers to relationship-focused leadership).

This leader assigns someone to a job or task and then expects it to be accomplished without any oversight.

has a high concern for tasks but a low concern for establishing or fostering relationships with its followers.

the manager is almost entirely concerned with establishing or fostering relationships with their followers.

“effective integration of people with production is possible by involving them and their ideas in determining the conditions and strategies of work.

is the assumption that “people are practical, they realize some effort will have to be exerted on the job.

The basic idea is that leaders and followers exist within a dyadic relationship; therefore, understanding leadership requires examining the nature of that relationship.

describes how leaders develop different relationships with individual team members, rather than treating all subordinates the same.

lead employees by aligning employee goals with the leader’s goals.

ensures that employees demonstrate the right behaviors and provide resources in exchange.

refers to behaviors leaders demonstrate that create confidence in, commitment to, and admiration for the leader.

is a leadership approach that defines the leader’s role as serving the needs of others.

Its key advice is “be yourself.” Authentic leaders are introspective, understand their origin, and thoroughly understand their values and priorities.