Presentation Aids

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Explain the reasons why presentation aids are essential in public speeches.

- Detail how presentation aids function.

- Discuss strategies for implementing and integrating presentation aids.

When you give a speech, you present much more than just a collection of words and ideas. Because you are speaking live, your audience will aesthetically experience your speech through all five senses: hearing, vision, smell, taste, and touch. In addition to your verbal and nonverbal communication, presentation aids help amplify your content to enhance the audience’s overall experience. Presentation aids are the resources beyond a speaker’s speech to enhance the message conveyed to the audience. The type of presentation aids that speakers most typically make use of are visual aids: pictures, diagrams, charts and graphs, maps, and the like. Audible aids include musical excerpts, audio speech excerpts, and sound effects. A speaker may also use fragrance or food samples as olfactory (sense of smell) or gustatory (sense of taste) aids. Finally, presentation aids can be three-dimensional objects or change over time, as in the case of a how-to demonstration. As you can see, you have a range of presentation aids available to you.

Two questions guide effective presentation aids:

- How can I effectively convey an idea in my speech using a presentation aid?

- When is the best time to introduce it to the audience?

If you can answer these two main questions, the audience is more likely to understand your idea more fully. Each speaker’s presentation aid must be a direct, uncluttered example of a specific speech element. Understandably, someone presenting a speech about Abraham Lincoln might want to include his photograph. Still, if there’s a high probability that the audience knows what Lincoln looked like, the picture would not contribute much to the message unless the message was explicitly about the changes in Lincoln’s appearance during his time in office. In this example, other visual artifacts may be more likely to deliver relevant information—a diagram of the interior of Ford’s Theater where Lincoln was assassinated, a facsimile of the messy and much-edited Gettysburg Address, or a photograph of the Lincoln family, for example. The key is that each presentation aid must directly express an idea in your speech.

Moreover, presentation aids must be used when presenting specific ideas related to the aid. For example, if you are speaking about coral reefs and one of your supporting points is about the location of the world’s major reefs, it would make sense to display a map of these reefs while talking about location. If you display it while explaining what coral is or describing the kinds of fish that feed on a reef, the map will not be a helpful aid; it’s likely to be a distraction. This chapter will discuss some principles and strategies to help you incorporate effective presentation aids into your speech. We will begin by discussing the functions that good presentation aids fulfill. Next, we will explore some of the various types of presentation aids and how to design and utilize them effectively. We will also describe multiple media that can be used for presentation aids.

Functions of Presentation Aids

Why should you use presentation aids? If you have adequately prepared and rehearsed your speech, shouldn’t a good speech with a good delivery be enough to stand on its own? While it is true that impressive presentation aids will not rescue a poor speech, it is also essential to recognize that a good speech can often be made even better by the strategic use of presentation aids. Remember that your speech is an experience rather than the isolated transmission of information so that presentation aids can enhance or detract from the aesthetics.

Presentation aids can fulfill several functions:

- improve your audience’s understanding of the information you are conveying;

- enhance audience memory and retention of the message;

- Add variety and interest to your speech.

- Enhance your credibility as a speaker.

Let’s examine each of these functions.

Improving Audience Understanding

Human communication is a complex process that often leads to misunderstandings. If you are like most people, you can easily remember incidents when you misunderstood a message or when someone else misunderstood what you said to them. Misunderstandings happen in public speaking just as they do in everyday conversations. One reason for misunderstandings is that perception and interpretation are highly complex, individual processes (remember that communication is always cultural and contextual rather than a universal set of symbols). Most of us have seen the image in which, depending on our perception, we see either the outline of a vase or the facial profiles of two people facing each other, known as the Rubin’s vase (Hasson et al, 2001). Or you may have listened to a song for years, only to have a friend say, “Uh, those aren’t the lyrics!” These examples demonstrate how interpretation can differ, and it means that your presentations must be based on careful thought and preparation to maximize the likelihood that your listeners will understand your presentation as you intend them to. As a speaker, one of your basic goals is to help your audience understand your message. Presentation aids can clarify or emphasize ideas to reduce misunderstanding.

Use Table 35.1 to identify questions that underlie clarifying or emphasizing ideas.

|

Table 35.1 Improving Audience Understanding |

||

|

To clarify: Simplifying complex information |

Am I describing a complex process that could be represented in a different way? Am I referencing ideas that are visual or sensory? |

Suppose your speech is about the impact of the Coriolis Effect on tropical storms, for instance. In that case, you will likely have difficulty clarifying it without a diagram, as the process is complex. |

|

To emphasize: Impress your listeners with the importance of an idea

|

Is there an idea or aspect of the speech that needs to be underscored? |

Let’s say you’re describing the increased prevalence of super tornadoes across Colorado over the last 30 years. You may decide that a map will visually highlight the sudden increase in storms. |

Aiding Retention and Recall

The second function that presentation aids can serve is to increase the audience’s chances of remembering your speech. An article by the U.S. Department of Labor (1996) summarized research on how people learn and remember. The authors found that “83% of human learning occurs visually, and the remaining 17% through the other senses—11% through hearing, 3.5% through smell, 1% through taste, and 1.5% through touch.” For this reason, exposure to an image can serve as a memory aid to your listeners. When your graphic images deliver information effectively and your listeners understand them clearly, audience members will likely remember your message long after your speech. An added plus of using presentation aids is that they can boost your retention and memory while you are speaking. Using your presentation aids while rehearsing your speech will familiarize you with the association between a specific point in your speech and the accompanying presentation aid.

Adding Variety and Interest

A third function of presentation aids is to make your speech more interesting. For example, wouldn’t a speech on community gardens have a greater impact if you accompanied your remarks with pictures of such gardens? You can imagine that your audience would be even more enthralled if you could display the produce live for them. Similarly, if you were speaking to a group of gourmet cooks about spices, you might want to provide tiny samples they could smell and taste during your speech.

Enhancing a Speaker’s Credibility

The final function of a presentation aid is to increase your ethos, or credibility. A high-quality presentation will contribute to your professional image. Thus, besides containing important information, your presentation aids must be clear, clean, uncluttered, organized, and large enough for the audience to see and interpret correctly. Misspellings and poorly designed presentation aids can damage your credibility as a speaker. Even if you give a good speech, you risk appearing unprofessional if your presentation aids are poorly executed.

Additionally, ensure that you appropriately credit the source of any presentation aids you use from other sources. Using a statistical chart or a map without adequate credit will detract from your credibility, just as using a quotation in your speech without credit would. This situation usually involves digital aids such as PowerPoint slides. A chart’s source or the data shown in a chart form should be cited at the bottom of the slide and orally in your speech. Suppose you focus on producing presentation aids that effectively contribute to your message. If they look professional and are handled well, your audience will most likely appreciate your efforts and pay close attention to your message. That attention will help them learn or understand your topic in a new way and will thus enable the audience to see you as a knowledgeable, competent, and credible speaker. With the prevalence of digital communication, the audience’s expectation of quality visual aids has increased.

Avoiding Common Presentation Aid Pitfalls

Using presentation aids can come with some risks. However, with some forethought and adequate practice, you can choose presentation aids that enhance your message and boost your professional appearance in front of an audience. One key principle to remember is to use only as many presentation aids as necessary to effectively present your message or clarify a key component of your idea. Too often, speakers fall into the “must have long and detailed presentational aids for the entire speech”. In these cases, the aid can overshadow or distract from the content, rather than clarify or add emphasis. Instead, simplify as much as possible, emphasizing the information you want your audience to understand rather than overwhelming them with too much text and images. Using blank slides between images can help the audience focus on you as the speaker and avoid being distracted by an image from a previous part of the speech that remains on the screen.

Another essential consideration is context. Remember to survey the literal context of your speech to determine what aid is possible—is there technology available? Is there a poster stand or a whiteboard? Are there speakers? Is there WiFi? Keep your presentation aids within the limits of the available working technology. Whether or not your technology works on the day of your speech, you will still have to present. As the speaker, you are responsible for arranging the necessary materials to ensure your presentation aids function as intended. Carry a roll of duct tape so you can display your poster even if the easel is gone. Find an extra chair if your table has disappeared. Test the computer setup. Have your slides on a flash drive AND send them to yourself as an attachment or post to a cloud service. Have an alternative plan prepared in case a glitch prevents your computer-based presentation aids from being usable. Most importantly, ensure you know how to use the technology effectively.

Next, presentation aids do not “speak for themselves.” When displaying a visual aid, explain what it shows, pointing out and naming the most important features. If you use an audio assistance such as a musical excerpt, you must tell your audience what to listen for. Similarly, if you use a video clip, it is up to you as the speaker to point out the video’s characteristics that support your point. Still, probably beforehand, so you are not speaking over the video. At the same time, a visual aid should be quickly accessible to the audience. This is where simplicity comes in. Just as in the organization of a speech, where you would use 3-5 main points, not 20, you should limit the categories of information on a visual aid.

Finally, creating accessible aids for the entire audience is essential. Imagine a speaker bringing up a chart with a bright flashing light to emphasize a point. For many audience members, this may not be a concern. However, for someone who suffers from chronic migraines, this might trigger a headache that ruins their day. Using accessibility checkers built into programs such as Microsoft PowerPoint or utilizing websites like WebAIM are ways to ensure that each audience member in your presentation can access the information in your visual aid. Consider the following questions:

- Is my font choice easy to read?

- Did I select a font size that can be read from anywhere in the room, including the back row?

- Does my color scheme provide enough contrast for the audience to see? Lime green on a dark green background is unreadable. High contrast, such as a light background with dark font, is easier to read.

- Do my videos have closed captioning? If not, can I find a transcript I can make available to the audience?

Asking these questions can help ensure that all audience members can

Types of Presentation Aids

Now that we’ve explored some basic hints for preparing presentation aids, the next step is to determine the best type of presentation aid. We’ll discuss types of aids that fall into two categories: representations of data and/or representations that display a real process, idea, person, place, or thing. In other words, ask yourself: “What type of information do I think needs to be accentuated? A statistic? An image of an idea?” Once you answer, the categories below can help you determine which aid would best display that type of information.

Representations of Data

If you want to clarify a complex piece of data or evidence from your speech, you may choose a chart, graph, or diagram. Charts, graphs, and diagrams help represent statistics, processes, figures, or other numeric evidence that may be difficult to comprehend if spoken.

Chart: A chart is commonly defined as a graphical representation of data or a diagram that illustrates an ordered process. Whether you create your charts or do research to find those that already exist, they need to match your speech’s specific purpose. Figure 7.5.1 (“Acupuncture Chart”) shows a chart related to acupuncture and may be helpful in a speech about the history and development of acupuncture. However, if you aim to show the locations of meridians (the lines along which energy is thought to flow) and the acupuncture points, you may need to select an alternative image.

There are two common types of charts: statistical charts and sequence-of-steps charts.

- Statistical Charts: For most audiences, statistical presentations should be kept as simple as possible and clearly explained. When visually displaying information from a quantitative study, ensure that you understand the material and can effectively explain how to interpret the data. This is undoubtedly an example of a visual aid that delivers limited information but does not speak for itself. As with all other principles of public speaking, KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE.

- Sequence-of-Steps Charts: Charts are also helpful when explaining a process that involves several steps. If you are working on a scientific or medical argument, you may need to visually map the sequence because it can be challenging to follow.

Graph: A graph is a pictorial representation of the relationships between quantitative data, using dots, lines, bars, pie slices, and similar elements. Graphs illustrate how one factor (such as size, weight, or number of items) varies in comparison to other items. A statistical chart may report the mean (or average) ages of individuals entering college, but a graph would show how the mean age changes over time. A statistical chart may report the number of computers sold in the United States. At the same time, a graph will use bars or lines to show the breakdown of those computers by operating systems such as Windows, Macintosh, and Linux. Public speakers can show graphs utilizing a range of different formats. Some of those formats are specialized for various professional fields. Very complex graphs often contain too much information that is not related to the purpose of a speech. If the graph is cluttered, it becomes difficult to comprehend. If you find a graph with helpful information, ask: “Do I need to represent this graph as-is, or can I represent a key portion of the graph that’s most relevant to my data?”

We’ll introduce three types of graphs: line graphs, bar graphs, and pie graphs.

- Line Graph: A line graph is designed to show trends over time. You could, for example, use a line graph to chart Enron’s stock prices over time.

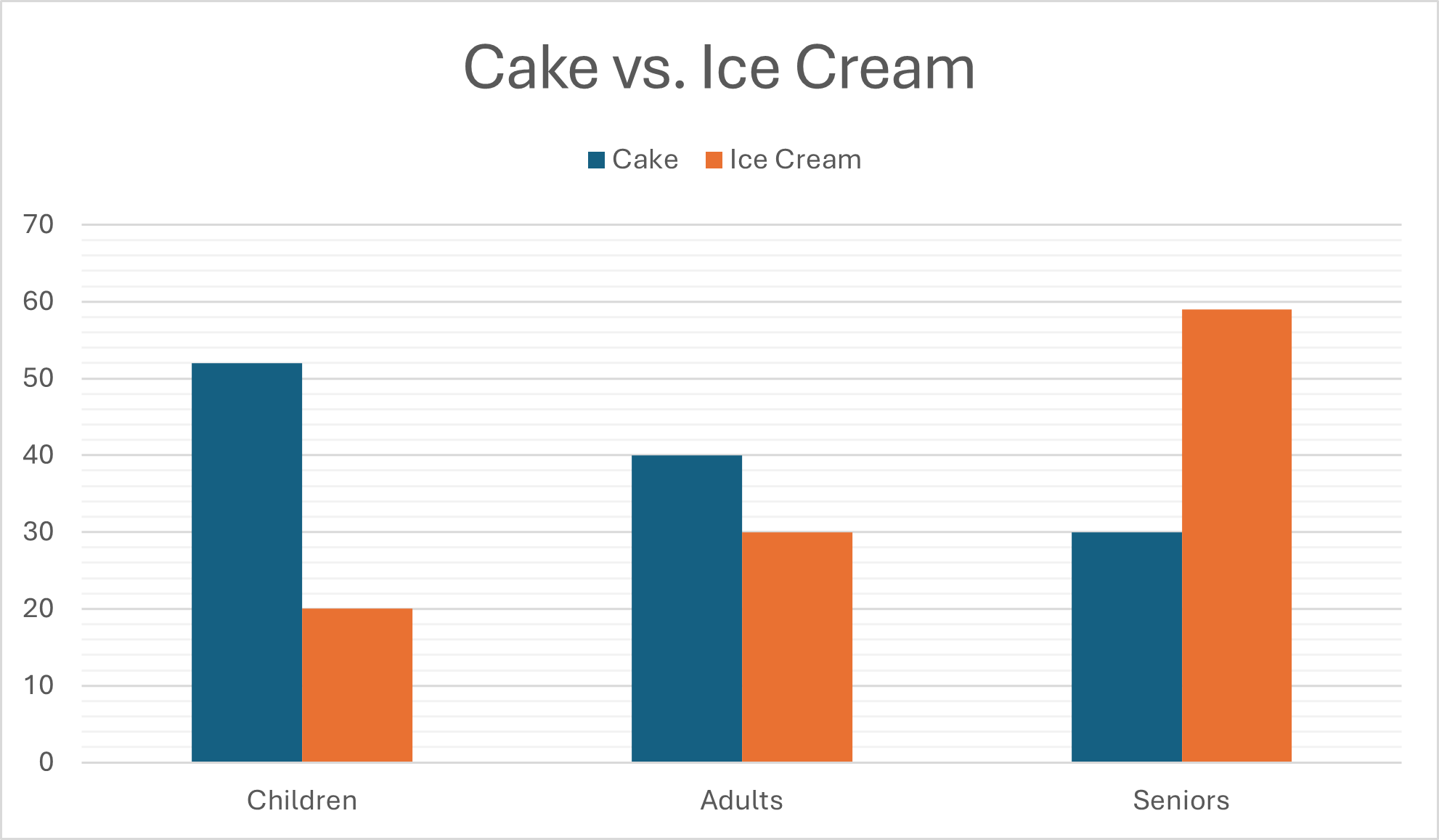

- Bar Graph: Bar graphs help show the differences between quantities. They can be used for population demographics, fuel costs, math ability in different grades, and many other kinds of data. The graph in Figure 35.2 (“Cake vs. Ice Cream”) is well designed. It is relatively simple and carefully labeled, making it easy to guide your audience through the recorded preferences for ice cream to cake based on age. When examining the data, the first group of children who prefer cake to ice cream is easily identified and explained during a presentation.

- Pie Graph: Pie graphs are typically depicted as circles designed to illustrate proportional relationships within data sets; in other words, they represent parts or percentages of a whole. They should be simplified as much as possible without eliminating important information.

Diagrams are visual representations that simplify complex processes. They may be drawings or sketches that outline and explain the parts of an object, process, or phenomenon that cannot be readily seen. When you introduce a diagram, you are working to label parts of a process for your audience. For example, you may decide to diagram how human communication occurs because simply describing that process would be too complex. Charts, graphs, and diagrams can present challenges in terms of being both practical and ethical. To be both ethical and effective, you must understand statistics and create or use graphs that display amounts. Remember that clarifying is a key goal of presentational aids, so ask: Is my graph or chart making my information more or less difficult to comprehend?

Representations of Real Processes or Things

In contrast, a second set of presentational aids represents real processes, things, persons, places, or ideas. While charts and graphs simplify more complex or abstract concepts, data, or evidence, this set of aids attempts to emphasize actual people, places, or objects. Such aids may include maps, photos, videos, audio recordings, and objects (diagrams can also fall into this category, depending on your mapping).

Maps are handy when the information is clear and concise. There are all kinds of maps, including population, weather, ocean current, political, and economic maps, so you should find the right type for your speech. Select a map that highlights the information you need to convey and that accurately represents your intended message. For example, you might decide that a map outlining the Hawaiian Islands would be helpful to clarify the spatial dimensions of the state. Although the map may not list the names of the islands, it helps orient the audience to the direction and distance of the islands from other geographic features, such as the Pacific Ocean.

Photographs and Drawings: Sometimes a picture or a drawing is the best way to show an unfamiliar but essential detail. For example, if you gave a speech about the impact of plastics on ocean life, you may decide to include a photo of a beached whale that had suffered from plastic inhalation. The photo may emphasize the impact of plastic that speaking otherwise doesn’t capture.

Video or Audio Recordings: A video or audio recording is another valuable presentation aid. Whether it’s a short video from a website like YouTube or Vimeo, a song segment, or a podcast piece, a well-chosen video or audio recording can enhance your speech.

One major warning about using audio and video clips during a speech: do not forget that they are supposed to aid your speech, not the speech itself! In addition, be sure to avoid these four mistakes that speakers often make when using audio and video clips:

- Avoid choosing clips that are too long for the overall length of the speech.

- Practice with the audio or video equipment before speaking. If you are unfamiliar with the equipment, you’ll look foolish trying to figure out how it works. Ensure the computer speakers are on and at the right volume level.

- Cue the clip to the appropriate place before beginning your speech, and try to avoid any advertisement interruptions (which can make the aide look unprofessional).

- Before the video or audio clip is played, the audience must be given context, specifically what the clip is and why it relates to the speech. At the same time, the video should not repeat what you have already said but add to it.

- Ensure that your video includes closed captions that play during the video, or provide a transcript to the audience through a digital source with a QR code or print versions for individuals to use.

Objects: Objects refer to anything you could hold up and talk about during your speech. If you’re discussing the importance of avoiding plastic water bottles, you might use a plastic bottle and a stainless steel water bottle as examples.

Ways to Display Your Presentation Aid

Above, we’ve discussed why you might use a presentation aid and what aid might work best. “How do I display these?” you might be wondering. For example, if you decide that a graph would help clarify a complex idea, you can present it to the audience using presentation software or more low-tech means. We’ll talk through each below.

Using Presentation Software

Presentation software and slides are a standard mechanism for displaying information to your audience. You are likely familiar with PowerPoint, but there are several others:

- Prezi, (paid product)

- SlideRocket, (paid product)

- Google Slides, (free)

- Keynote, (free)

- Impress, (free)

- PrezentIt, (paid product)

- ThinkFree, (free)

- E-Maze, (paid)

- Adobe Acrobat Presenter

Each software allows you to present professional-looking slides. For example, you can use the full range of fonts, although many are inappropriate for presentations because they are hard to read. Use Table 35.3 to track the advantages and disadvantages of using slides.

|

Advantages of Using Slides |

Disadvantages to Using Slides |

|

|

Remember that presentation software aids are a way to display what you want your audience to know—a graph, an idea, an image. Presentation software is not the only way to display these, so slides should be a purposeful choice. What you display is the top priority. Before we continue, we have one note: You’ll notice that “text from the speech” is not included in our list of types of presentation aids in the section above. You may decide that adding emphasis to a key word or concept from your speech is needed, and that’s OK! You may even choose that providing that concept, visually, for the audience is worthwhile by writing or displaying the words, and that’s OK, too. However, remember that presentation aids are included for a reason, and it’s often unnecessary to provide an entire outline of your speech’s text through a presentation software like PowerPoint slides. Speakers, too frequently, copy and paste parts of their speech onto a PowerPoint slide and think, “There! A presentation aid!” Ask: What purpose does this text serve for my audience? If your answer doesn’t result in clarifying, emphasizing, or retaining, it’s likely not needed.

Creating Quality Slide Shows

Slides should show sound design principles, including unity, emphasis or focal point, scale and proportion, balance, and rhythm (Lauer & Pentak, 2000). Presenters should also pay attention to tone and usability. With those principles in mind, here are some tips for creating and using presentation software.

- Unity and Consistency: Your visuals should look like a unified set, using a single (readable) sans serif font, a single background, and unified animations. Each slide should convey one clear message, accompanied by a relevant photo or graphic.

- Emphasis, Focal Point, and Visibility: All information should be large enough—at least 24-point font—for audiences. To guarantee visibility, keep your information clear and straightforward. Focus on illustrating points with your text, rather than letting the text drive the visual aid. Finally, it provides a higher contrast between the text and the slides.

- Tone: Fonts, color, clip art, photographs, and templates all contribute to tone, which is the attitude being conveyed in the slides. Ensure the presentation software’s tone matches the speech’s overall aesthetic tone.

- Scale and Proportion: Use numbers to communicate a sequence. If bullet points are used, the text should be short. Adjust graphs or visuals on the slide, avoiding small or multiple visuals on the same image.

- Balance and rhythm: Work to create symmetry and balance between each slide. When presenting, consider what is being displayed on the slide to the audience and when it will be shown. If you aren’t using it, insert a black screen between images.

- Usability: Include “alt text”—or a description of the image —with any picture or graphic. Prove that alt text is helpful for users with screen readers.

Low-Tech Presentation Aids

In addition to presentation slides, other “low-tech” ways exist to display information. Instead of providing a diagram on PowerPoint, you may decide that drawing it live is more beneficial. Below, we discuss a few additional ways to display your information to the audience.

Dry-Erase Board

Using a chalkboard or dry-erase board, your display should still be thought-out, rehearsed, and professional. You risk appearing less prepared, but numerous speakers effectively utilize chalk and dry-erase boards. Typically, these speakers use the chalk or dry-erase board for interactive components of a speech. For example, maybe you’re giving a speech in front of a group of executives and need to collect ideas in real time. Chalk or dry-erase boards are helpful for visually capturing audience feedback. Even in webinars, you can create a digital whiteboard to collect data. If you ever use a chalk or dry-erase board, follow these five simple rules:

- Write large enough so everyone in the room can see (which is harder than it sounds; it is also hard to write and talk simultaneously!).

- Print legibly; don’t write in cursive script.

- Write short phrases; don’t take time to write complete sentences.

- Never turn your back on the audience while you’re talking.

Flipchart

A flipchart helps save what you have written for future reference or to distribute to the audience after the presentation. As with whiteboards, you will need good markers, readable handwriting, and a strong easel to keep the flipchart upright.

Posters

Posters often represent a key graph, idea, or visualization. For a poster, you likely want to display one key piece of information at one key part of your presentation. Posters are probably not the best way to approach presentation aids in a speech. There are also problems with visibility and portability. Avoid creating a presentation aid that resembles a collage of copied and pasted magazine pictures.

Handouts

Handouts are appropriate for delivering information that audience members can take away with them. As we will see, handouts require much management to contribute to your credibility as a speaker. First, ensure the handout is worth making, copying, and distributing. Does the audience need the handout? Could the handout be delivered electronically through a link or QR code? Second, bring enough copies of the handout for each audience member to get one. Sharing or looking on with one’s neighbor does not contribute to a professional image. Third, consider timing. We recommend providing the handout after your speech. Otherwise, the audience will read the handout and miss parts of your presentation.

Reminders for Integrating Presentation Aids

Regardless of what presentation aid you choose—a photo, chart, map—and the medium that you’ll display it—a handout, slide deck, audio device—all presentation aids require rehearsal. While we’ve included tips on integrating presentation aids in your speech throughout this chapter, use the following list of strategies to integrate your aids into the speech.

- Gather all citation information and provide it visually and orally to your audience.

- In your speaking notes, mark where you will integrate the presentation aid so that you don’t forget about it due to nervousness.

- Determine where the presentation aid will be when it’s not being displayed.

- For a PowerPoint presentation, include blank/black slides used when your visual aid isn’t in use.

- Store other objects in non-distracting locations.

- Rehearse your transitions into and out of the presentation aid.

The Mythical Norm and Presentation Aids

As an audience member, you must reflect on your assumptions about the speaker. Are we judging a speaker based on our assumptions of what’s normal? Similarly, when making decisions about presentation aids as a speaker, it’s important to be reflexive about who is in the audience. Are you making decisions about presentation aids based on your assumptions about what’s normal and who’s normal? Are you assuming, for example, that all audience members are able-bodied and able to visually and audibly experience your presentation aid? Creating an accessible experience for audience members must be a priority. For example, you may want to avoid red and green colors on your visual aids as they’re not perceivable to all audience members. When creating presentation software for slides, ensure that you include alt-text for images, especially if you plan to distribute the slides. These are for audience members who may be sight-impaired. Check out the guidelines for the presentation software you’re using on how to embed alt-text. Additionally, be cautious of smells that may be intense or irritating to audience members. Overall, be careful not to assume that audience members also fit the mythical norm as you construct your presentation aid.

Conclusion

This chapter has covered a wide range of information about audio and visual aids; however, audiences today expect and appreciate professionally designed and well-handled presentation aids. The stakes are higher now, but numerous tools are available.

Key Takeaways

To finish this chapter, we will recap a few key pieces of information. Whether your aid is a slide show, object, or dry erase board, these standards are essential:

- Your audience should be able to access and experience presentation aids easily.

- Presentation aids must be portable, easily handled, and efficient. They should disappear when not in use.

- Presentation aids should be visually appealing and tasteful. Additionally, electronic media today allows you to create very “busy” slides with various fonts, colors, collages of photos, etc. Keep in mind the principles of unity and focal point.

- Color is another aesthetic aspect. Some colors are just more soothing, readable, and appropriate than others. Additionally, the color on your slides may differ when projected from what appears on your computer.

- Provide credit when using images that aren’t your own.

- Finally, presentation aids must support your speech and be highly relevant to your content.

Attribution

This chapter is adapted from “Speak Out, Call In: Public Speaking as Advocacy” by Meggie Mapes (on Pressbooks). It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

are the resources beyond a speaker's speech to enhance the message conveyed to the audience.

pictures, diagrams, charts and graphs, maps, and the like.

include musical excerpts, audio speech excerpts, and sound effects.

fragrance or food samples

fragrance or food samples