How Personality and Perception Affect Communication

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define perception and explain how it shapes communication in organizations.

- Identify common perceptual biases related to self and others.

- Explain how visual and social perception influence behavior in workplace settings.

- Describe attribution theory and its implications for organizational communication.

Perception isn’t just about what you see; it’s about how you make sense of the people and situations around you. In organizations, perception shapes how we interpret messages, build relationships, and make decisions. It’s also a significant reason for miscommunication, even when everyone thinks they’re being clear. This section will help you understand how perception works, including how we see ourselves and judge others. You’ll explore common perceptual biases, such as assuming someone is lazy based on a single missed deadline, and how these assumptions can impact team dynamics. You’ll also learn about attribution theory, which explains behaviors by determining whether we blame people or the situation, and why that matters in the workplace.

Why Perception Matters

You’ve probably heard the phrase, “Perception is reality.” In organizational communication, that’s more than just a cliché; it’s a driving force. Our interactions at work are shaped by what is said and done, as well as how we interpret those messages and behaviors. Whether welding in a shop, managing a retail team, or presenting in a meeting, understanding how people perceive you and how you perceive them can make or break communication. Perception is not just about seeing; it’s about interpreting what you see. And those interpretations are filtered through personality traits, past experiences, emotions, values, and even job roles.

What Is Perception?

Perception is how individuals detect and interpret environmental stimuli (Higgins & Bargh, 1987). It’s how we make sense of our world, including our workplace. However, we don’t just passively absorb facts. We notice what we care about, filter out what we don’t, and often draw conclusions based on incomplete or biased information. Think about walking into a job site or break room. If you’re anxious about your performance, you might interpret a co-worker’s neutral look as disapproval. Conversely, if you feel confident, you might interpret the same look as one of deep thought or admiration.

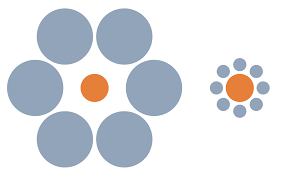

Visual Perception in the Workplace

Visual perception extends beyond raw data; it’s about what we perceive as we see. For example, research shows we perceive size, importance, or motion inaccurately based on the context surrounding an object (Kellman & Shipley, 1991). This might mean assuming a coworker is “fast and efficient” simply because they work near someone slower and less organized. Our brains constantly compare and contrast, and sometimes unfairly. Another example: You might think someone is always “on their phone” during work hours, but you miss that they’re checking the shift schedule or responding to a supervisor’s message. Our eyes can deceive us.

Self-Perception Biases

We don’t just misjudge others, we misjudge ourselves, too.

-

Self-enhancement bias: Overestimating our performance or value. This can lead to confusion when promotions don’t occur or feedback doesn’t align with our self-view (John & Robins, 1994).

-

Self-effacement bias: Underestimating our performance or value. People with low self-confidence may downplay their contributions, which can result in being overlooked for promotions or team leadership roles.

-

False consensus effect: Assuming others think or act the way we do. This can lead to poor ethical choices, such as rationalizing dishonesty with the notion that “everyone takes shortcuts sometimes” (Fields & Schuman, 1976; Ross, Greene, & House, 1977).

Perceiving Others: Social Biases

Much of workplace communication depends on how we perceive the people around us. Unfortunately, that perception is full of shortcuts:

-

Stereotypes: Generalizations about groups that affect individual judgment (Snyder et al., 1977).

-

Selective perception: We tend to see what confirms our beliefs and ignore what challenges them (Weingarten, 2007).

-

First impressions are formed quickly and stick, even if later information contradicts them (Ross et al., 1975).

For example, Miguel, a new welder at a fabrication shop, makes a small mistake in his first week. His supervisor might assume Miguel is careless, even if that mistake was due to unclear instructions. Later, even after Miguel becomes one of the most efficient welders on the team, that early impression might linger.

Attribution: Why We Think People Do What They Do

When people behave a certain way, we ask ourselves, “Why?”

- Attribution refers to the explanations we form about people’s behavior. We make:

-

Internal attributions (it’s something about them).

-

External attributions (it’s something about the situation).

The three key factors that influence which attribution we make are:

-

Consensus: Do others act the same way?

-

Distinctiveness: Does this person act this way in other situations?

-

Consistency: Does this behavior happen regularly? (Kelley, 1967, 1973)

Let’s say Miguel misses a safety meeting. If he’s the only one (low consensus), and he skips meetings often (high consistency), people might assume he’s irresponsible (internal attribution). However, if others also missed it (high consensus), and he usually attends meetings (low consistency), they may assume that something external caused the absence, such as a scheduling mix-up. Additionally, people tend to view themselves more favorably than they view others, a phenomenon known as the self-serving bias (Malle, 2006). We often blame circumstances when we fail, but take credit when we succeed. Awareness of this bias helps us give others the same benefit of the doubt we give ourselves.

Perception in Action: Workplace Examples

Here are some real-world communication problems caused by perception issues:

-

Shift change misunderstandings: A quiet, introverted night shift worker may be seen as aloof or unhelpful by a more extroverted day shift worker who expects casual updates and friendly check-ins.

-

Job interviews: First impressions during an interview can outweigh qualifications. That’s why small things like eye contact, posture, and tone carry extra weight quickly (Bruce, 2007; Mather & Watson, 2008).

-

Feedback sessions: Employees who self-efface may not speak up during a performance review, leading their supervisor to misread their level of satisfaction or readiness for additional responsibility.

Summary: Why Perception Belongs in This Course

Perception is the invisible filter that shapes every single message in an organization. It affects how people speak, listen, act, and interpret. Understanding these filters helps you become a more thoughtful communicator, a better collaborator, and a fairer leader. As you advance in your career, whether in welding, IT, healthcare, or education, your ability to critically examine your perceptions, recognize biases, and consider alternative viewpoints will become increasingly essential.

Key Takeaways

- Perception influences how we communicate, interpret messages, and form judgments in the workplace. What you see (or think you see) is shaped by your background, personality, and values, not just objective facts.

- Visual perception is context-dependent. We interpret what we see based on the surrounding information. This can lead to flawed conclusions about others’ performance or intentions.

- Self-perception biases matter. Some people overestimate their abilities (self-enhancement), while others underestimate themselves (self-effacement). Both can impact communication, confidence, and workplace dynamics.

- We assume others think like us. The false consensus effect causes people to overestimate the prevalence of their behaviors or beliefs, potentially normalizing unethical conduct.

- Stereotypes and selective perception skew how we view others. These shortcuts may lead to unfair treatment, communication breakdowns, or missed opportunities for collaboration.

- Attributions explain how we assign cause to behavior. We decide whether someone acted due to their personality (internal) or the situation (external), but these judgments are often biased.

- First impressions are powerful—and sticky. Knowing how quickly we form judgments (and how long we hold onto them) can improve fairness and reduce miscommunication.

References

Bruce, C. (2007, October). Business Etiquette 101: Making a good first impression. Black Collegian, 38(1), 78–80.

Fields, J. M., & Schuman, H. (1976). Public beliefs about the beliefs of the public. Public Opinion Quarterly, 40(4), 427–448.

Higgins, E. T., & Bargh, J. A. (1987). Social cognition and social perception. Annual Review of Psychology, 38(1), 369–425.

John, O. P., & Robins, R. W. (1994). Accuracy and bias in self-perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 206–219.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 15, 192–238.

Kelley, H. H. (1973). The processes of causal attribution. American Psychologist, 28(2), 107–128.

Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P. C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(5), 740–752.

Malle, B. F. (2006). The actor–observer asymmetry in attribution: A (surprising) meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(6), 895–919.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The false consensus effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(3), 279–301.

Ross, M., Lepper, M. R., & Hubbard, M. (1975). Perseverance in self-perception and social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(5), 880–892.

Snyder, M., Tanke, E. D., & Berscheid, E. (1977). Social perception and interpersonal behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(9), 656–666.

Weingarten, G. (2007, April 8). Pearls before breakfast. The Washington Post. https://wapo.st/3QqWWKL

how individuals detect and interpret environmental stimuli.

Overestimating our performance or value

Underestimating our performance or value

Assuming others think or act the way we do.

Generalizations about groups that affect individual judgment

We tend to see what confirms our beliefs and ignore what challenges them

refers to the explanations we form about people’s behavior

it’s something about them

it’s something about the situation

people tend to view themselves more favorably than they view others