Intrapersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Discuss intrapersonal communication.

- Define and discuss self-concept.

Before communicating effectively with others, you must understand the conversation inside your head. That’s where intrapersonal communication comes in. The internal dialogue shapes how you see yourself, interpret messages, and make decisions. This section will examine how your self-concept and understanding of your identity influence your communication style. You’ll also learn why becoming more aware of your inner thoughts and beliefs can help you build stronger, more authentic interactions with others.

Intrapersonal Communication and Self-Concept

Have you ever been caught staring off into space when someone asks, “What are you doing?” Maybe you’re scrolling through your phone, thinking about dinner, or debating whether to text your friends back. Whatever’s going on, it’s not just about what you’re doing—it’s also about what you’re thinking, feeling, and planning. That’s intrapersonal communication.

What is Intrapersonal Communication?

Intrapersonal communication is the conversation you have with yourself. It includes self-talk, imagination, daydreaming, and even mental problem-solving. According to McLean (2005), it can involve everything from replaying a memory to making a to-do list or giving yourself a pep talk. Let’s say you get a message about friends visiting your favorite restaurant. You might picture the food, remember a fun night you had there, or hear your inner voice weighing whether to go. Perhaps you envision your boss reprimanding you for skipping work, or your friends cheering you on for taking a break. That whole back-and-forth is intrapersonal communication. Shedletsky (1989) explains that this kind of internal communication still employs all the typical elements of a communication exchange (such as sender, receiver, message, feedback, and noise). Still, they all occur within your mind. Pearson and Nelson (1985) also note that intrapersonal communication encompasses planning, goal-setting, reflection, and resolving personal conflicts. It’s a constant process, quiet, but powerful.

Your Self-Concept

When we talk to ourselves, we often shape how we perceive ourselves. That’s called self-concept, or “what we perceive ourselves to be” (McLean, 2005). Self-concept encompasses your personality, values, motivations, and self-perception. Psychologist Charles Cooley introduced the idea of the looking-glass self—the idea that we learn about ourselves by watching how others react to us. If people treat us respectfully, we begin to believe we deserve it. If they dismiss us, we might question our worth. Leon Festinger (1954) expanded on this concept with his social comparison theory, which explains how we compare ourselves to others to determine our self-evaluation. So when you wonder, “Who am I?” Part of the answer comes from inside and how others reflect you to yourself.

The Role of Self-Talk

That little voice inside your head? That’s your internal monologue. Sometimes it’s helpful, like when you’re organizing your thoughts. Other times, it can get in the way, especially if it’s critical, negative, or loud enough to drown out what others say. Alfred Korzybski (1933) suggested that learning to quiet one’s inner voice is a key step toward more transparent communication. It’s a skill: noticing when one jumps to conclusions or plans one’s response while someone else is still talking, and instead choosing to listen.

Why This Matters

Communication doesn’t just happen between people; it occurs within people. When you communicate with others, your inner dialogue shapes how you listen, respond, and interpret their message. That dialogue also shapes your motivation, confidence, and decision-making when alone. The takeaway? Your internal communication affects your external relationships, and understanding that can help you be more intentional and effective in all areas of life.

Dimensions of Self

Who are you? You are more than your actions, and more than your communication, and the result may be greater than the sum of the parts, but how do you know yourself?

Exercises

- Define yourself in five words or fewer.

- Describe yourself in no less than twenty words and no more than fifty.

- List what is important to you in priority order. List what you spend your time on in rank order. Compare the results.

Was the above exercise a challenge? Can five words capture the essence of what you consider yourself to be? Was your twenty to fifty description easier? Or was it equally challenging? Did your description focus on your characteristics, beliefs, actions, or other factors associated with you? What did you observe if you compared your results with your classmates or coworkers? For many, these exercises can prove challenging as we try to reconcile the self-concept we perceive with what we desire others to perceive about us, as we try to see ourselves through our interactions with others, and as we come to terms with the idea that we may not be aware or know everything there is to know about ourselves.

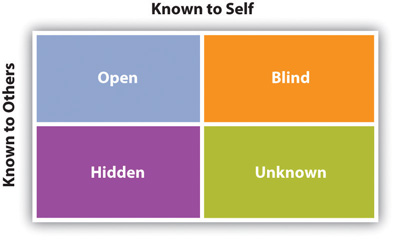

Joseph Luft and Harry Ingram gave considerable thought and attention to these dimensions of self, which are represented in Figure 3.1.1 “Luft and Ingram’s Dimensions of Self”. In the first quadrant of the figure, information is known to you and others, such as your height or weight. The second quadrant represents things others observe about us that we are unaware of, like how many times we say “umm” in five minutes. The third quadrant involves information you know but do not reveal to others. It may involve actively hiding or withholding information, such as social tact, like thanking your Aunt Martha for the large purple hat she’s given you, knowing you will never wear it. Finally, the fourth quadrant involves information unknown to you and your conversational partners. For example, a childhood experience that has been long forgotten or repressed may still have a lasting impact on you. As another example, how will you handle an emergency after you’ve received first aid training? No one knows because it has not happened.

These dimensions of self remind us that we are not fixed—that the freedom to change, combined with the ability to reflect, anticipate, plan, and predict, allows us to improve, learn, and adapt to our surroundings. By recognizing that we are not fixed in our “self” concept, we come to terms with the responsibility and freedom inherent in our potential humanity. In the context of business communication, the self plays a central role. How do you describe yourself? Do your career path, job responsibilities, goals, and aspirations align with what you recognize as your talents? How you represent “self,” through your résumé, in your writing, in your articulation and presentation—these all play an essential role as you negotiate the relationships and climate present in any organization.

Key Takeaways

- In intrapersonal communication, we communicate with ourselves.

- Self-concept encompasses multiple dimensions and is expressed through internal monologues and social comparisons.

References

Cooley, C. (1922). Human nature and the social order (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Scribners.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relationships, 7, 117–140.

Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and sanity. Lancaster, PA: International Non-Aristotelian Library Publish Co.

Luft, J. (1970). Group processes: An introduction to group dynamics (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: National Press Group.

Luft, J., & Ingham, H. (1955). The Johari Window: A graphic model for interpersonal relations. Los Angeles: University of California Western Training Lab.

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Pinker, S. (2009). The stuff of thought: Language as a window to human nature. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Shedletsky, L. J. (1989). Meaning and mind: An interpersonal approach to human communication. ERIC Clearinghouse on reading and communication skills. Bloomington, IN: ERIC.

Attribution

Business Communication for Success Copyright © 2021 by Southern Alberta Institute of Technology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

the conversation you have with yourself, including self-talk, imagination, daydreaming, and even mental problem-solving.

what we perceive ourselves to be

the idea that we learn about ourselves by watching how others react to us.

how we compare ourselves to others to determine our self-evaluation.

The little voice inside your head