Horizontal/Lateral Communciation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Explain the perspective on horizontal/lateral communication.

- Understand the four functions of horizontal/lateral communication.

- Analyze five organizational behaviors to increase the quality and quantity of horizontal/lateral communication in multinational corporations.

Not all communication flows from the top down or bottom up. Much of what keeps organizations running smoothly happens laterally, between coworkers, departments, or teams operating at similar levels of authority. This kind of horizontal communication is essential for collaboration, coordination, and building relationships across silos. In this section, we’ll explore the key functions of horizontal communication and its importance, particularly in complex or global organizations. You’ll also learn how certain behaviors can improve both the quality and quantity of lateral communication, making it more likely that ideas, updates, and decisions move across an organization efficiently and respectfully.

Horizontal (or Lateral) Communication

Horizontal communication, sometimes called lateral communication, happens between people on the same level in an organization. This might be two coworkers on the same team, two managers in different departments, or two supervisors with equal responsibility. It’s communication across the organization rather than up or down the chain of command. These communication lines are sometimes built into an organization’s structure, like a standing committee or department meeting. However, they often occur informally: a brief hallway chat, a group text, or a side conversation during a project.

Where the Idea Comes From

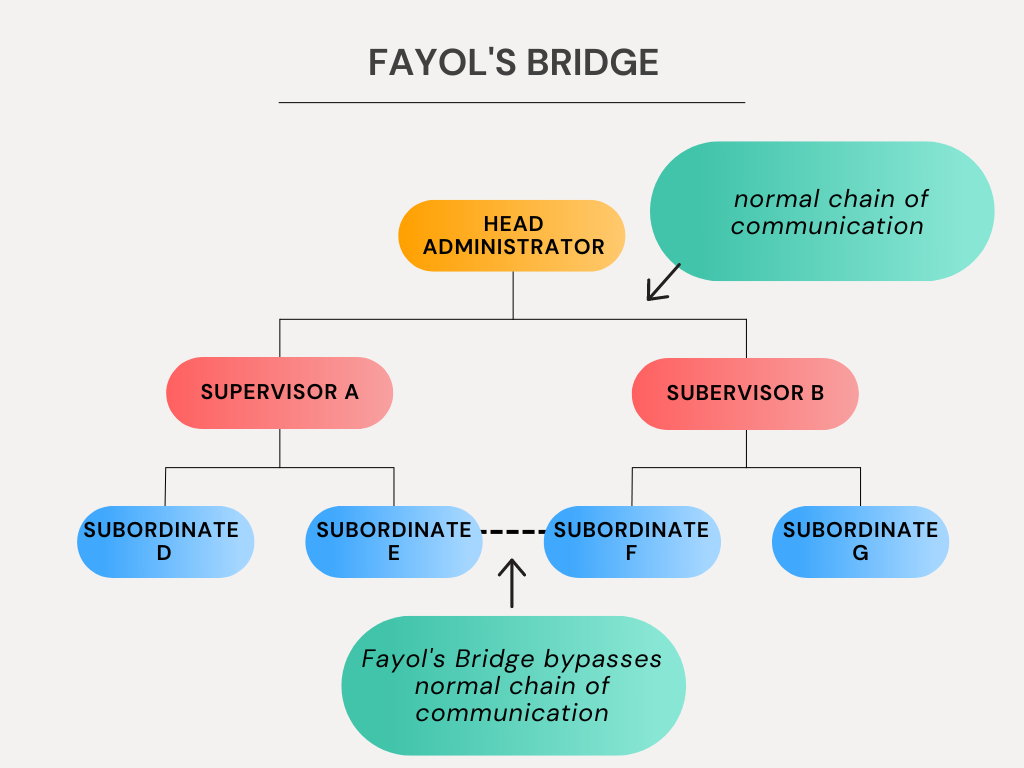

One of the first to discuss this kind of communication was a French mining engineer named Henri Fayol. He wrote a book in 1916 about how businesses should be organized, but it was not translated into English until 1949. In it, he described how communication in an organization should follow a strict chain of command, going up the ladder and back down again. For example, imagine an organization with one head manager, two supervisors, and six workers—three reporting to each supervisor. Fayol believed that if Employee E, who works under Supervisor B, needed to communicate with Employee F, who works under Supervisor C, the message would need to travel up through Supervisor B and the head manager, and then down through Supervisor C to reach Employee F in the end. It’s a long and formal process, but that’s how organizations were expected to run at the time.

Exceptions in a Crisis

Fayol also recognized that this slow, top-down communication isn’t always practical during emergencies. So, he proposed an exception: in a crisis, employees at the same level should be allowed to communicate directly with one another. This temporary “shortcut” across the hierarchy was his way of acknowledging that sometimes speed matters more than formality. Today, most organizations recognize that horizontal communication is essential, not just in emergency situations, but also in everyday collaboration. It helps employees solve problems, build teamwork, and share information faster. However, the extent to which workers have the freedom to communicate across levels or departments depends on the organizational culture and management style.

Fayol’s Bridge and the Evolution of Horizontal Communication

Henri Fayol’s concept of “the bridge” significantly altered how organizations viewed communication. Typically, messages in a hierarchy had to go up the chain of command and back down. But Fayol acknowledged that in emergencies, that process took too long. So he proposed a flexible shortcut: if Employee E had urgent information needed to reach Employee F (someone on the same level but under a different supervisor), E could go through Supervisor B and ask permission to send the message directly to F. If Supervisor B agreed that speed was more important than following the chain of command, they would allow the direct message to happen. This “bridge” approach added efficiency in times of crisis, while still keeping authority in place.

Communication in the Mid-20th Century

For much of the early 20th century, the belief was that messages should always flow vertically, up and down through the chain of command. Horizontal communication between departments was discouraged unless it went through higher-ups. Here’s how it was described in 1951:

“Reports, desires for services, or criticisms that one department has of another should be sent up the line… then held, revised, or sent directly to the appropriate officials and departments… to inform higher officials of things occurring below them.”

— Miller & Form, 1951, p. 158

In other words, managers were expected to control the flow of information, even between employees at the same level. However, as time passed, researchers began to question this model.

A Shift Toward Horizontal Communication and Decentralization

By the 1960s and 1970s, scholars and business leaders recognized that strictly vertical communication was unrealistic and unhelpful. Organizations functioned better when lower-level supervisors and employees were allowed to communicate across departments and make decisions independently. Joseph Massie (1960) referred to this shift as “automatic lateral communication,” meaning supervisors no longer required permission to solve problems; they could communicate directly with their peers to get things done. This kind of communication became routine and expected, rather than rare or exceptional. This shift led to a more flexible structure known as decentralization, where decision-making power is distributed across the organization, rather than concentrated at the top (Child, 2005; Hilmer & Donaldson, 1996).

Decentralization:

-

Saves time by allowing people closest to the problem to make decisions.

-

Frees up senior leaders from having to manage every minor issue.

-

Encourages faster, more natural communication across departments.

Avoiding the Pitfalls of Serial Communication

Another reason decentralization helps is that it reduces the risks of “serial communication.” When a message has to pass through multiple layers of a hierarchy, it’s more likely to be misunderstood, altered, or distorted (Redding, 1972). Think of it like the game of telephone: the more people a message passes through, the more likely it is to get scrambled.

What Does Horizontal Communication Do?

Randy Hirokawa (1979) outlined four primary functions of workplace horizontal, or lateral, communication. These functions enable employees across various departments or teams to work together more effectively. Here’s a breakdown of what horizontal communication is used for and why it matters:

1. Task Coordination

This ensures that different departments or coworkers collaborate smoothly to reach shared goals. Without team communication, tasks can be duplicated, delayed, or done in ways that harm other parts of the organization. For example, if the marketing team launches a campaign before the production team is ready, it creates unnecessary pressure and miscommunication. But when both teams coordinate, things run more efficiently. Sometimes, departments don’t even realize how much they rely on each other until they begin discussing their needs. Horizontal communication creates that awareness.

2. Problem Solving

Many workplace problems can’t be solved by just one department. System-wide issues need system-wide solutions. For example, if your company is trying to reduce energy waste or improve recycling, you’ll need input from facilities, operations, finance, and even frontline employees. Brainstorming across departments brings different perspectives and often better answers. Hirokawa (1979) emphasized that cross-department collaboration leads to stronger problem-solving than any group could manage alone.

3. Sharing Information

We’ve all seen what happens when people hoard information, repeat tasks, make mistakes, and feel left out or confused. Horizontal communication helps solve this by encouraging the open sharing of ideas, updates, and knowledge between peers. Hirokawa (1979) put it this way: “It is through the sharing of information that organizational members become aware of the activities of the organization and their colleagues” (p. 89). In short, people work more effectively when they are informed about what’s happening in their department and across the organization.

4. Conflict Resolution

Sometimes, people clash. Perhaps it’s due to shared resources, missed deadlines, or personality differences. Horizontal communication enables employees to communicate directly with one another and resolve misunderstandings before they escalate. Most workplace conflicts are easier to solve with a simple, direct conversation. But if you remove that direct line of communication, as Fayol once recommended, you’d have to go up and back down the hierarchy to talk to a colleague (Hirokawa, 1979, p. 89). That wastes time and often makes things worse. Maintaining direct and respectful communication helps resolve issues more quickly and protects working relationships.

Zappos’ Holacrazy Organizational Structure

In 2015, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh broke down and explained a new approach to organizational structure: holacracy. Watch the video below to learn more about this structure. As you do so, consider the implications for downward, upward, and horizontal/lateral communication.

Why Horizontal Communication Sometimes Fails

Like upward and downward communication, horizontal (or lateral) communication has problems. In fact, a study by Wilmot Associates found that over 60% of employees across various industries reported ineffective communication with coworkers or across departments (McClelland & Wilmot, 1990). Nearly half felt communication within their department wasn’t working well, and 70% believed communication between departments needed serious improvement. So what’s going wrong? Researchers have pointed to four common challenges that get in the way:

1. There’s No Reward for It

Let’s be honest: we’re more likely to do something when we know it’s valued or rewarded. However, historically, organizations haven’t recognized or rewarded people for talking across departments (Hirokawa, 1979). If the system only praises results or individual performance, people stop prioritizing communication that doesn’t directly benefit their role. The result? Missed opportunities, duplicated work, and disconnected teams.

2. Departments Compete Instead of Collaborating

In many U.S. workplaces, departments are under subtle (or not-so-subtle) pressure to compete for resources, recognition, or influence. This mindset leads people to withhold information, trying to get ahead or avoid helping another team. Hirokawa (1981) pointed out that this competitive culture tends to be more common in American businesses, while Japanese companies focus more on collaboration and, in turn, experience stronger lateral communication.

3. Ongoing Conflict Between Teams

Communication often breaks down when there’s ongoing tension between departments or coworkers, whether it concerns responsibilities, priorities, or past missteps. People stop engaging, stop listening, or avoid talking altogether. This creates silos where teams focus inward, rather than outward.

4. People Don’t Understand Each Other’s Jobs

McClelland and Wilmot (1990) referred to this problem as a lack of lateral understanding. If employees don’t know what their coworkers in other departments do, it leads to:

-

Wasted time trying to figure out who’s responsible for what

-

Overlap (two people unknowingly doing the same work)

-

Poor decisions that affect others down the line

Even senior leaders can fall into this trap, making changes without realizing the impact those changes have on other parts of the organization.

So, How Do We Fix It?

McClelland and Wilmot (1990) not only identified the problems but also suggested seven innovative strategies to enhance the effectiveness of horizontal communication. Here’s how organizations can get better:

1. Help People Understand Each Other’s Roles

Encourage employees to learn about the work of other departments. You can do this through orientation programs, job shadowing, cross-training, or hosting regular team forums. When people understand how different teams operate, it’s easier to collaborate rather than duplicate efforts.

2. Create a More Flexible Chain of Command

Rigid hierarchies don’t work in every situation. If communication always has to go up and then down again, it slows things down and creates frustration. Instead, empower people to communicate directly with others at their level when needed, without having to jump through unnecessary hoops.

3. Send Clear, Consistent Messages from the Top

If senior leadership isn’t aligned, departments get mixed messages. That confusion trickles down and damages trust. Consistency matters. Everyone should get the same info simultaneously, so it doesn’t feel like one team is being prioritized over another.

4. Set the Example from the Top

Want employees to talk more across departments? Leaders need to model that behavior. When supervisors collaborate, check in with peers, and treat other teams respectfully, it encourages staff to do the same.

5. Build Cross-Departmental Teams

Create teams that include representatives from various departments to collaborate on shared goals. But don’t just create the team, give them decision-making power. When people are trusted to make fundamental changes, they’re more invested in solving problems together.

6. Hold People Accountable to the Whole Organization

It’s easy for departments to focus only on their own goals. However, a good organization makes sure everyone sees the bigger picture. When decisions from one team affect another, they should collaborate to resolve the issue, rather than passing the blame.

7. Train People How to Communicate Better

Not everyone is naturally comfortable reaching out across departments. Some employees—especially in technical or independent roles—may not know how to have these conversations. Offer training in interpersonal communication, teamwork, and constructively giving feedback.

Bonus Tip: Improve Shift and Location Communication

In 24/7 or multi-site workplaces, communication between shifts or locations is often overlooked. But it’s vital. Leaving detailed handoffs between shifts or using shared logs can prevent errors and improve efficiency. The more people know what has already been done (and what still needs to happen), the smoother their shift will go.

In Summary

Horizontal communication is a significant issue, but also a substantial challenge. Organizations need to reward, support, and model it from the top down to make it work. The entire system benefits when employees understand their colleagues’ roles and feel empowered to collaborate.

Key Takeaways

- Henri Fayol (1916/1949) believed that organizations needed a strict organizational hierarchy in which all information flowed up and down appropriate channels.

- Hirokawa (1979) identified four primary functions of horizontal communication: task coordination, problem-solving, information sharing, and conflict resolution. The function of horizontal/lateral communication is to help organizational members coordinate tasks, enabling the system to achieve its goals.

References

Fayol, H. (1949). General and industrial management (C. Storrs, Trans.). London: Pitman. (Reprinted from Administration industrielle et générale, 1916)

Hirokawa, R. Y. (1979). Communication and the managerial function: Some suggestions for improving organizational communication. Communication, 8, 83–95.

Massie, J. L. (1960). Automatic horizontal communication in management. Journal of the Academy of Management, 3, 87–91, pg. 88

McClelland, V. A., & Wimot, R. E. (1990). Improve lateral communication. Personnel Journal, 69, 32–38.

Miller, D. C., & Form, W. H. (1951). Industrial sociology. New York: Harper.

Simpson, R. L. (1959). Vertical and horizontal communication in formal organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 4, 188–196.

Attribution

Organizational Communication Copyright © by Dr. Sarah Hollingsworth is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This happens between people on the same level in an organization. This might be two coworkers on the same team, two managers in different departments, or two supervisors with equal responsibility.

Founder of Modern Management Methods. Fayol wrote a book in 1916 about how businesses should be organized. In it, he described how communication in an organization should follow a strict chain of command, going up the ladder and back down again.